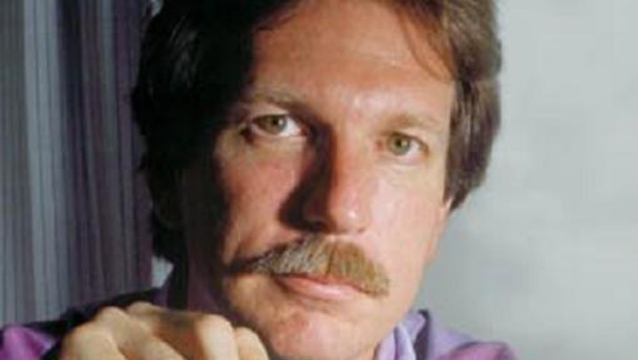

Investigative reporter Gary Webb, who exposed the link between the CIA and the crack cocaine epidemic in his groundbreaking “Dark Alliance” series, officially resigned from the San Jose Mercury News. The resignation followed a settlement between Webb and the newspaper over a grievance Webb filed over his transfer from the paper’s Sacramento bureau to its suburban Cupertino office. He was transferred after the publication of his 1996 “Dark Alliance” series, which linked the rise of crack cocaine in urban America with the CIA and the U.S.-organized contra army in Nicaragua. While the series struck a sympathetic chord throughout much of urban America, it also provoked a fierce reaction from the media establishment, which denounced the series. Following the controversy, San Jose Mercury News Executive Editor Jerry Ceppos demoted Webb to the suburban office.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: You’re listening to Pacifica Radio’s Democracy Now! The Exception to the Rulers. I’m Amy Goodman. Investigative reporter Gary Webb, who exposed the link between the Central Intelligence Agency and the crack cocaine epidemic in his ground-breaking “Dark Alliance” series, has officially resigned from the San Jose Mercury News. The resignation follows a settlement between Webb and the newspaper over a grievance Webb filed over his transfer from the paper’s Sacramento bureau to its suburban Cupertino office. He was transferred after the publication of his ’96 “Dark Alliance” series, which linked the rise of crack cocaine in urban America, particularly in South Central Los Angeles, with the Central Intelligence Agency and the U.S. organized contra army in Nicaragua.

While the series struck a sympathetic chord throughout much of urban America, it also provoked a fierce reaction from the media establishment, which denounced the series. Following the controversy, San Jose Mercury News editor Jerry Ceppos demoted Webb to a suburban office of the paper.

We’re joined right now by Gary Webb from his home.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

GARY WEBB: Hi, Amy. How are you doing?

AMY GOODMAN: Good. Well, the more important question is: How are you doing?

GARY WEBB: Hey, I’m alive. I’m here, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: Well—

GARY WEBB: And not working for that newspaper anymore, thank God.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, tell us exactly what happened.

GARY WEBB: Well, what happened was, you know, like you said, they transferred me out to the boondocks, and I went on a byline strike, and I wouldn’t allow my name to be used on any stories while I was out there. And, you know, that made everybody even madder. And then, you know, I finally had to sit down and figure out—you know, this is a year and a half now since the series came out, and what am I doing with my life, and what am I doing with my work that’s meaningful? And I had to answer that, you know, nothing was happening. You know, it was clear to me that the Mercury—I mean, they had told me that, you know, even when we won the arbitration, that they weren’t going to let me do anything worthwhile. They were not going to let me do any investigative reporting. So I had to figure, you know, this is kind of pointless to hang around and work for a newspaper whose editors you didn’t respect and do dog bite stories for the rest of my life. It just didn’t seem worthwhile.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk a little about how the arbitration went?

GARY WEBB: Well, we never got that far. A couple of days before the hearing was scheduled, there was a settlement offer. And as I said, you know, it suddenly became a lot more attractive than—you know, even winning the arbitration, I lost, because I was still working for the same group of gutless editors that I would be working for before, so, you know, the settlement was, you know, I thought, good enough to take. And so we did. And it never got to a hearing.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, tell us about the articles that you wrote that actually never made it to the San Jose Mercury News, although they allowed you to write them.

GARY WEBB: Yeah, well, they not only allowed me to write them, they sent me down to Central America and then had me doing research for a number of months and turn them in. And they were never edited. I mean, I turned them in, and nobody ever sat down and went through them with me. Nobody ever said, “Well, let’s see the documentation for this. Let’s see your notes for that.” Nobody did anything. They just made this unilateral decision that they weren’t going to run them. And then, I mean, the thing that was shocking about it is when they made that decision and, you know, sent me off to Cupertino and took me off the story, Jerry Ceppos got up on The Washington Post and New York Times, and then he just lied and said, you know, there weren’t any stories, which really told me that things were kind of out of whack at this newspaper, when the executive editor can get up there and lie to The New York Times and Washington Post about stories that he’d read. You know, and then they’ve never run. And I doubt very seriously that they ever will. I mean, it’s been almost a year since I turned them in, and there hasn’t been any movement on that front as far as I know. So, you know, there they sit.

AMY GOODMAN: To say the least, Gary Webb, I’m very interested in reading them, and I look forward to your book coming out. But can you summarize for us, well, some of your findings, what you found in your investigations?

GARY WEBB: Well, the other four stories were primarily about the contra drug pipeline in Costa Rica and the involvement of the Nicaraguans, who were running the L.A. drug ring, with the DEA agents in Costa Rica. They also involved Oliver North’s role and his enterprises, operations and connections to this drug ring. They also involve an investigation into the DEA office in Costa Rica. There were allegations there that the agents were dealing drugs themselves. And it was a whole 'nother facet of this operation that we thought advanced the story considerably. I mean, it took it from being, you know, what a lot of people saw as a strange sort of aberration that a contra drug ring could have existed in the United States, to showing that it wasn't strange at all. I mean, there was another drug ring operating in Costa Rica. There was a very close and tight relationship between our premier anti-drug agency, the DEA, and the members of this L.A. drug ring. We thought it was significant. Jerry Ceppos didn’t think it was worth printing.

AMY GOODMAN: Gary Webb, for people who actually haven’t gotten a chance to read your “Dark Alliance,” it has been characterized and mischaracterized over and over again.

GARY WEBB: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: A lot of firestorm over your piece. How would you summarize your first series, the actual “Dark Alliance” series? And what have you learned from doing it?

GARY WEBB: Well, first of all, I mean, I would summarize it by saying that the story was about a drug ring that created the first crack market in the United States, down in South Central Los Angeles back in the early 1980s, and the fact that they were getting their cocaine from Nicaraguan contras, people who were using the money to finance the war down there in Nicaragua, you know, and the fact that they had been meeting with CIA agents at the time, before they started selling the dope and while they were doing it. And that’s really all it said. Everybody else jumped on it and said, “Oh, you’re accusing the CIA of creating crack to decimate the ghettos.” And, you know, I think a lot of it was sort of a straw man argument.

AMY GOODMAN: I guess a lot of the criticism was—or, some of the criticism was the crack cocaine epidemic in this country, in South Central Los Angeles, would have grown up even without the Nicaraguan contras backed by the [inaudible]—

GARY WEBB: Well, yeah, and that’s really sort of a silly argument. I mean, you can make that argument about anything. The fact of the matter is that this is the way it happened. You know, there was no crack down in South Central. And there would have been crack anyway. I doubt seriously if it would have been on this scale in that city without these Nicaraguans, who—you know, they brought in 50 tons of cocaine. And it’s awful hard to start a crack epidemic if you don’t have the cocaine to do it. You know, I heard a lot of people saying, “Oh, well, you know, this crack thing would have happened anyway, because people were poor, and they needed jobs, and, you know, bla bla bla bla bla.” But you can’t start a cocaine epidemic without cocaine. And that was my whole point in the series, was these were the men that brought in the cocaine that started the crack epidemic. So—

AMY GOODMAN: Gary, would you have done anything differently, had you known what you know today? And are there ways you would have written the “Dark Alliance” series differently?

GARY WEBB: Well, I wouldn’t have—I mean, it was originally four parts. And, you know, they thought that was too long, and they wanted it cut to three. I probably wouldn’t have done that. I don’t know what else—no, I don’t think I would have done anything else differently. I mean, I’m just sorry I had editors whose backbones weren’t quite what I thought they were when, you know, the series started taking some criticism. But you can’t predict that ever.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, an argument of a lot of the critics was that you never actually prove that the Central Intelligence Agency knowingly engaged in crack being brought into, cocaine being brought into this country, and particularly funneled into South Central Los Angeles. What’s your response to that?

GARY WEBB: Well, that was another little nicety. I mean, we had uncontroverted testimony and pictures of these drug dealers meeting with CIA agents. Now, whether they were talking about football scores or whether they were talking about cocaine, I don’t think is much of a question. Whether or not this was approved at the highest levels of the CIA, I would seriously doubt. I mean, even if they knew about it, they would never be so stupid as to officially approve an operation like this. This is something that happens with people knowing as little about it as possible. And, you know, you can’t prove anything that the CIA does one way or another, because you don’t get access to their records anyway. So, I mean, that was another silly kind of argument. People do newspaper stories all the time without proving one thing or another. You know, it’s not my job to prove things beyond a reasonable doubt. I’m not in the prosecution business; I’m in the newspaper business. And my job is to put the information out there and let people make up their own minds. And a lot of people made up their minds, after reading this story, that the CIA must have known about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Gary Webb is who we’re talking to right now, formerly a reporter with the San Jose Mercury News. He is leaving the San Jose Mercury News, has formally resigned. What are you going to do now?

GARY WEBB: Well, I’m writing the Dark Alliance book, which will be published in April by Seven Stories Press, and be able to put a lot of this information out there, including the stuff that we didn’t get in the Mercury. And I’m working for the California Legislature right now as a consultant to a government oversight committee.

AMY GOODMAN: Doing what?

GARY WEBB: Same thing I was doing before for the Mercury, you know, looking at state agencies and looking for waste and inefficiency and corruption and that sort of thing. And I’m doing it for the California Legislature now instead of for the Mercury News, and actually making more money.

AMY GOODMAN: Some might have hoped you would have maybe perhaps gone to work for Maxine Waters, who has taken up the issue of the CIA crack connection so vociferously and backed what you’ve been doing, and perhaps continued that investigation.

GARY WEBB: Well, I mean, with Georg—my partner Georg Hodel and I have continued the investigation on our own. I mean, we have not been doing nothing in the last year and a half. You know, we went back down to Nicaragua a couple of times, did some more interviews, dug up some more records at National Archives. So, we’ve continued to do the investigation, and that’s why I’m doing the book. So—but, you know, the other thing is that everybody in Washington is still waiting for the Justice Department and the CIA to finish their internal investigations about this. If you recall, when the stories came out, they announced these investigations and said they were going to be done within 60 days. Well, it’s been a year and a half now, and they’re still not done.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s right. I remember actually the former director of Central Intelligence, John Deutch, in that historic, what you could call, I guess, town hall meeting in South Central Los Angeles—

GARY WEBB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —as he said, “Well, we have to wait until the investigation is finished.”

GARY WEBB: Yeah, well, I wonder how many more CIA directors we’re going to go through before we actually get the results of that investigation. You know, they were talking that it was going to take years to do this thing, which makes me wonder—you know, it doesn’t take a year and a half to find nothing. You know, you can find nothing in 60 days very easily. If there’s nothing there, what’s taking them so long for the report to come out?

AMY GOODMAN: What about lessons around politics? I mean, before you did this series, you had never seen anything like the uprising that resulted, where people—the agitation, the anger, the organizing that came out of your “Dark Alliance” series. You ended up going to mass meetings of sometimes thousands—

GARY WEBB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —and speaking. How did this change your life? And what do you suggest to people who read your series, were galvanized by it, demanded action?

GARY WEBB: Well, I mean, the one thing that really changed my outlook on it was how powerful the press can be when it’s used in the correct way. I mean, when it actually tells people the truth about what the government is doing, when it doesn’t pull any punches and lays it out there, people respond to that. The reason nobody responds to most of the stuff you see in the paper any day is because nobody cares about it. You know, the most difficult question for me was, you know, and the question I was asked a lot is: What do we do about this now? Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot you can do, except let people in Washington know that they were angry and know that they wanted to get to the bottom of it, because they’re the ones that control the information. And that’s probably the most difficult part about doing an investigation like this of the government, is when the government controls all the information. And, you know, you get out bits and pieces, and you never know the 99 percent of the stuff that they’re sitting on. The problem was Congress was getting ready to respond to that. You know, if you looked at the hearings that the Senate Intelligence Committee held at the end of last year, there was a lot of anger and a lot of energy in that audience, and I think it frightened a lot of people in Washington. There have been no hearings since then.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, no question about it. When they had that first hearing, that we covered on Democracy Now!, I think they announced it perhaps that day, or the day before. Wasn’t this—

GARY WEBB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —held by Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania?

GARY WEBB: Well, and Specter also said that they were going to continue to do hearings on this. And after the second one, there have been no more. And the issue has gone underground, and it’s sort of gone away, which I think was the intent all along. I mean, this is a very bad issue for politicians in Washington on both sides of the political aisle, because, you know, you had a lot of Democrats who were supporting the contras right down the line. You had a lot of Democrats that voted for these increased crack penalties as a result of this epidemic that happened in the '80s. So, I mean, there's really no glory to be gained by outing the government that they’re part of. And I don’t think that—I don’t think you’re going to see that. That’s why I think this thing was shoved off to the Justice Department, shoved off to the CIA, for God knows how long, until everybody sort of forgot about this issue.

AMY GOODMAN: What about President Clinton? Has he ever made a comment on it?

GARY WEBB: He made a comment. I was talking to somebody who raised it to him at a party during the campaign. And he said, “Oh, that’s a real hot issue right now. We’re going to wait on that one.” So, you know, his drug czar came out and said this is a—you know, this is an issue that needs to be investigated, and that’s about it. I mean, a lot of people paid lip service to the thing at first. And I think once they realized that opening this door, they were going to get back into the situation that the government was in in the '70s, where you had the Pike Committee and the Church Committee, and you started opening CIA doors, and all these skeletons started tumbling out, and everybody got very scared and closed them back up again. You know, there's really no political gain for anybody to go poking around in the CIA’s dirty laundry, which is why I don’t think you can rely on politicians to do this.

AMY GOODMAN: Is there any chance, Gary Webb—when you work for the California State Legislature, I’m sure people are thinking now, actually, that’s not a bad place to investigate the U.S. government drug connection in this country, that you could go on doing those kind of investigations, when you talk about investigating state agencies. Any chance you could continue it just wearing this new hat?

GARY WEBB: I doubt it. You know, the stuff that I’m working on now has nothing to do with that. And frankly, you know, I’ve been doing this since 1995, and I’m—after I’m done with this book, I don’t know particularly if I’m going to be all that eager to jump right back into it again. And this is a very tiring, very wearying experience. And frankly, you know, considering what I’ve gone through, this is nothing compared to what my colleague in Nicaragua went through. I mean, he got death threats, and his house was vandalized.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Georg Hodel.

GARY WEBB: His wife’s office was burglarized. And he finally—you know, they finally left the country. So, this is not something you really make a career out of, nor would you want to. It’s very, very, very tense, very—you know, very scary kind of work.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you very much, Gary Webb, not only for being with us today, but for doing the work that you’ve done. We look forward to your book coming out. Do you have a title for it?

GARY WEBB: Dark Alliance.

AMY GOODMAN: Dark Alliance. Gary Webb, formerly a reporter with the San Jose Mercury News, now going to be an investigator in the California Legislature, and we’ll see where you go from there. Whether you would like to put this to rest and move on to other issues, I don’t think people will let you do that, especially when your book comes out. So we look forward to talking to you in just a few months.

Media Options