Guests

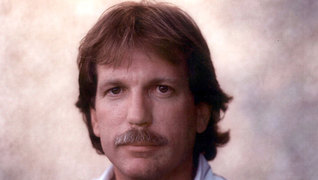

- Gary Webbjournalist for the San Jose Mercury News.

Jerry Ceppos, editor of the San Jose Mercury News, has made statements that the integrity of his paper’s story connecting the CIA to crack cocaine distribution in South Central Los Angeles and the military contras in Nicaragua. Amy and Juan are joined by Gary Webb, the journalist that first broke the story. Webb defended his journalistic integrity as well as the information in his articles about the L.A. drug ring.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: You’re listening to Democracy Now! I’m joined now by my co-host, Juan González, a columnist with the New York Daily News. Nice to see you again, Juan.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Good day, Amy. And how are you?

AMY GOODMAN: Good. And we’re going to start off with a piece we’ve both been following since last summer, when the San Jose Mercury News series began, and we’re going to talk about the latest development. The executive editor of the San Jose Mercury News has acknowledged that its controversial series suggesting a link between the CIA and cocaine trafficking was, quote, “oversimplified,” omitted important conflicting evidence and, quote, “fell short of my standards,” he said. He is Jerry Ceppos. He wrote in a column on Sunday that the “Dark Alliance” series “strongly implied CIA knowledge” that a drug ring linked to the Nicaraguan contras was selling crack in Los Angeles in the 1980s. And he said, quote, “I feel that we did not have proof that top CIA officials knew of the relationship. … We also did not include CIA comment about our findings, and I think we should have.”

Well, when they were originally published last summer, the “Dark Alliance” series of articles by investigative reporter Gary Webb caused a sensation, prompting black congressional leaders, headed by Congressmember Maxine Waters of Los Angeles, to demand an independent investigation into the role of the CIA in illegal drug trafficking. Then, CIA Director John Deutch went so far as to hold a town meeting in Los Angeles, where he said a full investigation into the allegations would be held. For its part, the media establishment, led by The New York Times, The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, attacked the articles and claimed that radio shows and street corner gossip had distorted the facts of the CIA’s role in drug trafficking.

Joining us right now to talk about this extraordinary move of the editor of the—executive editor of the San Jose Mercury News is Gary Webb, the reporter at the San Jose Mercury News who broke the “Dark Alliance” series. I should say, by the way, that we did invite Mr. Ceppos to join us, but he didn’t and just said his words stand on their own.

So we welcome you, Gary Webb, to Democracy Now!

GARY WEBB: Hi. It’s good to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, good to be with you. Why don’t you start out by telling us your reaction to Jerry Ceppos’s basically allegations against you, saying that you just engaged in shoddy journalism?

GARY WEBB: Well, I don’t think he said that. I mean, if you read the thing carefully—and believe me, you have to read it very carefully to get this out of it—he says that the story essentially is true, that, you know, the contras were selling cocaine in South Central Los Angeles, they were selling large quantities of it, and the money from the sales of the drugs were going to the war effort. And, you know, as he noted, we have solid documentation for that.

What he took issue with was a couple of things which I consider sort of trivial. And the other problem is that a lot of the criticisms he made in that column are moot, because we’ve been investigating this for eight months since, and we’ve come up with a lot of additional information that so far the Mercury has not printed. And it’s specifically on point with a couple of the issues he raises. Primarily, you know, one of the issues he says is that the figure that we used, which was sort of a broad figure of millions of dollars going to the contras, he said was an estimate. I think it’s obvious to a lot of people that when you don’t put a number on something, when you just use a phrase like “millions,” it is an estimate.

Subsequent to that, however, we’ve interviewed one of the couriers for this drug ring, who told us that he took $5 million to $6 million down in one year alone, in 1982. I tried to persuade Mr. Ceppos that this is information that we ought to share with the public, and so far we haven’t done that. The other problem is that we have evidence now of direct CIA involvement with this drug operation. We also have evidence of very high-level CIA knowledge of at least portions of it. Again, this is information that was turned in several months ago and has not appeared in the paper, and I can’t really get a straight answer as to why that information is just sitting there.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Gary, what kind of pressure came on the paper, as far as you can tell, in terms of the public outcry of this series from government institutions or the federal government itself?

GARY WEBB: I don’t know about any. I mean, there was pressure on us initially not to print this information about Danilo Blandón, who was one of the drug traffickers that we wrote about, from the DEA. I mean, they were insistent that we not do this, and tried to set up various enticements for us to leave that bit out. After the series appeared, I mean, there was a huge, huge controversy. And, you know, I think it was a situation where you had us against the world, essentially. You know, The New York Times, The Washington Post, the L.A. Times were all saying that, you know, this wasn’t any big deal, that there was only five tons of cocaine sold by these folks down in South Central. And I think, you know, journalists are like anybody: They succumb to peer pressure very easily—and which is I think why you don’t see more stories like this. If you go back to the '80s and look at what happened to Brian Barger and Bob Parry, when they did their contra cocaine stories back in the ’80s, the same thing. I mean, it was them against the entire rest of the press. And it's not a comfortable position to be in. I don’t mind it, because I know the story is true, but I think other people get a little knock-kneed when that happens.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, one of the things that your editor said in his letter was that the series had oversimplified the spread of the crack epidemic and blaming it sort of on Ricky Ross and its explosion eastward from Los Angeles. Yet, and I seem to recall that the L.A. Times itself had pinned a lot of the blame for the expanding crack epidemic on Ricky Ross years before. What’s your sense—do you think that that charge that the oversimplifying of the spread of crack was accurate?

GARY WEBB: No, I don’t think so at all. And I think it’s very clear, when you look at the historical record, that it started in South Central Los Angeles. It spread primarily through the gangs. I mean, there are federal government reports that we have which said that, you know, they found evidence of Crip crack dealing and Blood crack dealing in 45 cities in 32 states. And this was a couple of years ago, and it’s still spreading. I mean, part of the problem is that the media oftentimes believes its own propaganda. And one of the biggest propaganda efforts that I came across in the story was the idea that crack happened overnight, that in 1986 suddenly we woke up one morning and we were engulfed by this tidal wave of crack. And that’s pretty much the prevailing media belief to this day, which, you know, it’s nonsense. I mean, it started very slowly and started in South Central, and it took years to spread to other cities. So, I mean, I think Ceppos and I just disagree on the whole epidemiology of crack. And unfortunately, he’s the editor, and he gets to write a column, and I don’t. I mean, I stand by the story.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve said a few times now in this brief conversation that you have more evidence and that you’ve attempted to write more articles.

GARY WEBB: I have written more articles. They just haven’t appeared in the paper.

AMY GOODMAN: So what’s happening?

GARY WEBB: Nothing. They’re just sitting there. I mean, Georg Hodel, who is my Nicaraguan colleague who’s been working on this with me, we turned in four more parts of the series in February, and nobody’s even lifted a finger to edit them. They’re just sort of sitting there.

AMY GOODMAN: Didn’t Jerry Ceppos just call them notes?

GARY WEBB: He was quoted in the Times calling them notes. I was frankly astonished to see that. I mean, unless his definition of “notes” is different than 99 percent of the American public, that’s just not true. These were very long, very detailed stories.

AMY GOODMAN: Like the first series you did?

GARY WEBB: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, the second part of the series goes—I mean, it’s probably even more explosive than the first part. The second part deals with who in the government knew about this, which federal agents were either aware of this and did nothing or, in some cases, were working with the members of the drug ring. I mean, we’ve got a paper trail now that goes all the way into the National Security Council. And, you know, when we were sent out to do these additional stories back in October, the feeling at the newspaper was let’s go after, let’s get this stuff, let’s put this stuff in the paper, let’s shut everybody up. And I said, you know, “That’s a great idea.” We went down to Central America two more times, came back with what I thought was just dynamite stuff. And it has just sat there. And instead, we have this column that ignores a lot of the stuff that we found then and pretends it doesn’t exist and says, “Well, I guess—you know, I guess we weren’t as right as we thought we were.” The truth is we were more right than we knew.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Have you—I’m familiar with the whole process when you initially break a story, that you inevitably get all kinds of people coming forward with even more tips.

GARY WEBB: Yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I’m sure that must have happened. You must have been overwhelmed.

GARY WEBB: They were coming out of the woodwork, yeah. They were coming out of the woodwork. And people that I had been looking for for a year suddenly surfaced after the story came out. And we went down, and we interviewed them. We interviewed pilots that were flying this cocaine in and out of the country. We interviewed the man who was taking the money down there. It was really a mess. And, you know, we got—like I said, we were more right than we knew. I was astonished how deep this thing went.

AMY GOODMAN: Gary Webb, if you can’t publish this new series in the San Jose Mercury News, would you like to name the names here on Democracy Now!?

GARY WEBB: I’m going to give the Mercury the opportunity to print the stuff first. If I can’t reach some agreement with them, then I’ll have to see what else we can do. But, I mean, it’s a very—it’s a sort of a hard position to be in, to have your paper sort of take a dive on a story that you know is true, a story that they know is true, and pretend that we don’t have this other information.

AMY GOODMAN: Are you thinking about leaving?

GARY WEBB: No, I’m thinking about staying there and fighting to get these stories in the newspaper. I mean, whatever the situation is, I mean, I like the Mercury News. I’ve like working for it. I like the people there. I think it’s a good, honest newspaper. I find these latest moves to be very bizarre, however.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, let me ask you about that, because I’m personally familiar with one of the executives there, Jay Harris, the publisher, who I—

GARY WEBB: Right.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I used to work with him at the Philadelphia Daily News. And I generally considered him a more courageous news executive than most others, and certainly he’s one of the few African-American publishers, if not the only, of a major daily newspaper in the country.

GARY WEBB: Right.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: What has been Harris’s role? Has he met with you? Or has all the word from management come down directly through the editor?

GARY WEBB: You know, you’re talking about a level now that is not visible to mere mortals like me. I’m sure Harris was involved in some of this. What the extent of his involvement was, I don’t know. I mean, I did not talk to him about this.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, the paper has let you continue the investigation, presumably. You’re there as a regular reporter, and you’ve done this four-part series.

GARY WEBB: And that—right, and that’s all I’ve been working on since the series started. So, I mean, it seems to me—and certainly my immediate editor is intent on getting these other stories published. But, you know, I’ve got to tell you, I don’t think the chances are all that great, given the fact that the paper’s come out with this strange column, which says that we don’t have information that we do have.

AMY GOODMAN: Is there any direct CIA intervention there—I mean, even in taking the CIA seal that you had originally on the “Dark Alliance” series with a person smoking crack in the middle of it, taking that off?

GARY WEBB: If there was, I don’t know about it. You know, I’ve heard rumors that CIA attorneys showed up at the paper. I never heard or saw anything to substantiate that. Again, I mean, they don’t contact me. If there’s contact going on, it’s above my level. They don’t seem to like talking to me very much for some reason.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Gary Webb, we thank you for talking to us. Gary Webb, a San Jose Mercury News reporter, who broke the series, the “Dark Alliance,” last year, the story behind the crack explosion. And we do look forward to seeing these next series of articles published, hopefully in the San Jose Mercury News.

GARY WEBB: I hope so, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Thank you for being with us.

GARY WEBB: All right.

Media Options