Related

Topics

Guests

- Maya Angeloupoet and civil rights activist.

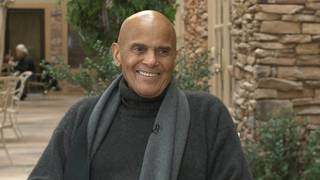

- Harry Belafontelegendary singer, actor and civil rights activist.

On Saturday thousands of mourners filled Riverside Church in Harlem for the funeral of Ossie Davis. Davis died Feb. 4 while on location for a film in Florida. He was 87 years old. For five decades, Ossie Davis led a distinguished career as an actor, playwright and director. Along with his wife, Ruby Dee, he was a renowned civil rights activist and an unforgettable figure in the African American struggle for equality. Speakers at Saturday’s funeral described the event as a state funeral for black America.

In his eulogy, Harry Belafonte said, “Among many gifts mastered, he was foremost a master of language. He understood the power of words and used them to articulate our deepest hope for the fulfillment of our oneness, with all humanity. Ossie Davis was born into a time of great promise. And guided by his fervent dedication to justice. He wasted no opportunity in defending the causes of the poor, the humiliated, the oppressed.”

Poet Maya Angelou said, “He belonged to us. He exists in us. We can be, and be more, every day more. Larger, kinder, truer, more honest, more courageous, and more loving because Ossie Davis existed and belonged to all of us.”

Former President Bill Clinton said, “[Ossie Davis] would have been a very good President of the United States.”

We spend the hour hearing excerpts from the funeral service: Belafonte eulogizing Ossie Davis as well as tributes from President Bill Clinton, writer Maya Angelou, Malcolm X’s daughter Attallah Shabazz, Davis’ grandson Brian Day and a musical tribute by jazz musician Wynton Marsalis. [includes rush transcript]

Thousands gathered at Riverside Church in Harlem to pay tribute to the actor and civil rights activist. He died February (4th) fourth while on location for a film in Florida. He was 87 years old. For five decades, Ossie Davis led a distinguished career as an actor, playwright and director. Along with his wife, Ruby Dee, he was a renowned civil rights activist and an unforgettable figure in the African American struggle for equality.

He performed in scores of movies, including six with director Spike Lee. In 1948, he married fellow actor Ruby Dee and the two were inseparable for the next 56 years.

In addition to their acting careers, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee had prominent roles on the nation”s political stages. They participated in marches for racial equality throughout the South and in the 1963 March on Washington. After Malcolm X was assassinated at a Harlem rally in 1965, Ossie Davis wrote and delivered the eulogy at his funeral. In 1968, he remembered Dr. Martin Luther King. Davis continued his activism up until his death, most recently protesting the war in Iraq and the coup in Haiti.

On Saturday, thousands of people packed into Riverside Church to attend the funeral.

The service included tributes by Ossie Davis’ children and grandchildren. Actors Alan Alda, Burt Reynolds, Angela Bassett and Spike Lee spoke–as did Attallah Shabazz, the eldest daughter of Malcolm X. Former president Bill Clinton also took the stage. Maya Angelou and Sonia Sanchez delivered poetic tributes and Wynton Marsalis performed. Avery Brooks read from “Purlie Victorious,” a play Davis wrote and starred in. Singer and actor Harry Belafonte delivered the eulogy at the ceremony.

- Maya Angelou

- Harry Belafonte

- President Bill Clinton

- Attallah Shabazz

- Brian Day

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin with poet Maya Angelou.

MAYA ANGELOU: About ten days ago Ossie and Ruby telephoned me, and asked if I would go and stand in for them at the Kennedy Center in Washington on this past Monday night. Ossie said, “It’s not much money.” So I said, “That doesn’t surprise me.” I said that I have something, I’m going to do disclose this to the world soon. In the 1960s or 1950s, Ossie and Ruby had a radio show, and they asked me to write something for it, write a piece. Two or three pieces. And I did. And they paid me $50. So, I just happened to have had the papers, the very papers I had written for them, and I said, “I’m going to show these to the world and show how good the writing was, and that you only paid me fifty bucks.” Whereupon Ossie said, “Girl, we only had a hundred. We gave you half. We should have given you 33 and a third.”

And then the heaviest door in the universe slammed shut. And there were no knobs. The season of grief fell around us like the leaves of autumn. When great trees fall, rocks on distant hills shudder. Lions hunker down in tall grasses, and even elephants lumber after safety. When great trees fall in forests, small things recoil into silence, their senses eroded beyond fear. When great souls die, the air around us becomes sterile, light, rare. We breathe briefly. Our eyes briefly see with a hurtful clarity. Our memory, suddenly sharpened, examines, gnaws on kind words unsaid, on promised walks not taken. Great souls die, and our reality, bound to them, takes leave of us. Our souls, dependent upon them, upon their nature, upon their nurture, now shrink, wizened. Our minds, formed and informed by their radiance, seems to fall away. We are not so much maddened as reduced to the unutterable silence of dark, cold caves. And then our memory comes to us again in the form of a spirit, and it is the spirit of our beloved. It appears draped in the wisdom of Du Bois, furnished in the humor and the grace of Paul Laurence Dunbar. We hear the insight of Frederick Douglass and the boldness of Marcus Garvey. We see our beloved standing before us as a light, as a beacon, indeed, as a way. We are not so much reduced. Suddenly the peace blooms around us. It is strange. It blooms slowly, always irregularly. Space is filled with a kind of soothing electric vibration. We see the spirit, and we know our senses. We change, resolved, never to be the same. They whisper to us from the spirit. Remember, he existed. He existed. He belonged to us. He exists in us. We can be, and be more, every day more, larger, kinder, truer, more honest, more courageous, and more loving, because Ossie Davis existed and belonged to all of us.

AMY GOODMAN: Poet Maya Angelou remembering Ossie Davis at his funeral.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to the funeral of Ossie Davis, held at Riverside Church on Saturday. Legendary actor, singer, activist Harry Belafonte delivered the eulogy.

HARRY BELAFONTE: 60 years is a long time to know somebody. 60 years is a long time to be hugging somebody and there comes a time when the end begins to evidence itself, that you realize that 60 years is really nothing more than a blink of an eye. Ossie Davis and I have shared a friendship for 60 years. And in our time together, we have seen many peaks and valleys. And in recent time, we observed each other carefully in how we did things. And when we were on a platform to service some community or human need, we would notice in one another that we were not walking today with the same energy and exuberance as we were able to do when we first met. And when would you sit down, we noticed that one another that — we did so a little more slowly to make sure we didn’t invite the nagging ache in the lower back before we were ready to experience it again. And on one such occasion just very short few days ago, Ossie and I, as we have done quite often in this time, began to reflect on not only what we have done but how much time is left to do what we felt we had to do. And he said to me, Harry, if it comes to be that I leave here before you, which is not my intention, nor my expectation, but if that happens, be sure that when you stand before those who are gathered that you don’t, for God’s sake, put any words in my mouth. I told him that that was not possible. In the 87 years he has lived, he has said just about everything that could be said and did so eloquently. Some things are not possible.

Words cannot be shaped to sufficiently soften the grief that many of us are feeling of the loss of our beloved Raiford Chatman Davis. His passing is no simple loss. The vastness of his being that he so humbly contained, can only now be revealed. Only with passing do we begin to truly sense how profound a force he was, and remains. All people embraced him, as he embraced all people. But he held a special place in the heart and soul of black folk and the poor. He was of them. He came from them. And from birth until death, he was always in the midst of their everything. Among many gifts mastered, he was foremost a master of language. He understood the power of words and used them to articulate our deepest hope for the fulfillment of our oneness, with all humanity. Ossie Davis was born into a time of great promise. And guided by his fervent dedication to justice. He wasted no opportunity in defending the causes of the poor, the humiliated, the oppressed. He embraced the greatest forces of our time — Paul Robeson, Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, Eleanor Roosevelt, A. Philip Randolph, Fanny Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Thurgood Marshall, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, and so many, many more. At a time of one of our most anxious and conflicted moments when our America was torn apart by seething issues of race, Ossie paused at the tomb of one of our noblest warriors, and in the eulogy he delivered insured that history would clearly understand the voice of black people, and what Malcolm X meant to us and the cause of the African and the African-American struggle for freedom. When many of our greatest warriors were most reviled, he championed to them and our cause. With history as witness, and his uncompromising allegiance to truth, Ossie Davis stands validated and revered.

There is no union more blessed than the bond that exists between Ossie and his compassionate and courageous mate, Ruby Dee. They are inseparable, and though one could easily believe that only in death would they be parted, even that stands to be proven. For their union was more than physical, their thoughts were one. Their utterances rapped in mutual approval, and their love made of a spirit that embraced the universe and all of its living creatures. The harmony of their song was filled with trust and respect. Together they imparted to a world caught in bitter struggle against injustice, the belief that solidarity welded to the deep commitment and belief in non-violence was and still remains the most powerful weapon in human kind’s arsenal of choice. Their children and grandchildren are the embodiment of what love can nurture, are their gift to our world, and our future. How fortunate for us all that Ruby remains in our family of fellow beings.

In 1917, if a black man had choice, Cogdell, Georgia, would not be his ideal place of birth. But it was in many ways this birthplace that shaped Ossie Davis’s values and courage. He came from a family of achievers, and their dignity and unwillingness to live and be defined as subhuman constantly enraged the already spiteful and cruel white community that surrounded them. The Ku Klux Klan’s declaration that they would shoot down his father like a dog caused Ossie in later life to claim that incident as a most compelling reason for exploring writing as a life profession. That exploration led him to Shakespeare, and the theater, and indeed, in the Thespian world, he found purpose. The performing arts became his rebellion to tyranny. And as an actor, he interpreted our existence with the dignity rarely allowed to the generations of black artists who struggled before him. The small few who did achieve his ability and dignity, like Paul Robeson, became Ossie Davis’s guide to a life of social activism that would forever fuel his passion to employee art as an instrument for battling injustice.

Black America has always lived in a state of siege, and in our 400 years of history and of living with this imposition, African-Americans have consistently fought for relief, and have placed faith and the belief that the articles of governance framed by the nation’s white founding fathers would one day fully embrace its citizens of color just as it has so generously embraced its white population. But that has not been our lot. By creating a zone of special privilege for but a small number of black citizens, there’s some who would give the impression that this privilege was the dominant condition of the whole of the black population, and nothing could be further from the truth. Ossie Davis, though touched by this seduction of the privileges of the elite as a movie star and a revered presence in our national culture, refused to distance himself from the vast majority of his people, and diligently championed our struggle for our rightful place at the table of America’s experiment with democracy. He despaired at the present state of our nation. He detested the lies and deceit that found favor in the minds and hearts of a vast number of our citizenry. Our nation’s arrogant and mindless imperial march toward global domination deeply concerned him. But he reminded those who lost heart in the face of this turn in human events, let us not linger on what is lost, but let us dwell on what it is we must do. Let us do what we know how to do. Let us forge an unbreakable solidarity and blow the dust off the blueprints of our past victories. Let us reclaim our undistorted moral truth, and turn all of this into a world of peace. Let us reclaim our earth and nurture with the love all of her living offsprings. Let us be worthy of why we are here, and reassert our national humanity. To do anything less for our America would have history charge us with being guilty of patriotic treason.

The richness of Ossie Davis’s wit and humor complimented his commanding intellect and compelling art. Once in my home at a not too uncommon ritual of planning for our emerging desegregation battle in Montgomery, Alabama, Dr. King, Stan Levinson, Bernard Lee, Ossie and a few others were listening to Bayard Ruston, our most knowledgeable on the application in Ghandian non-violent methodology. And Bayard guided us through steps of what to do if our marches were stopped by state troopers, what to do if we were tear-gassed or beaten, what not to do in retaliation, what to do in the paddy wagon, what to do what booked at the police station, what to say, when to resort to fasting if incarcerated long enough and so on and so forth. We listened carefully and asked questions, absorbing all we could, and went off over the following weeks to organize our demonstrations. On the March for the Selma, we planned for the tens of thousands of marchers to arrive that night just outside of Montgomery at a holding point given to us by the catholic church, a place called, St. Jude., the grounds were quite spacious. On the morning before the arrivals, to insure that morale and spirit of the marchers would not wane, we built a stage made from 120 coffins donated by two local funeral parlors on which dozens upon dozens of America’s most well known artists would perform. In my task to arrange all of this, I greated our chartered flights at Montgomery airport from Los Angeles and New York, crammed with our cultural luminaries. Stepping off the plane, behind Tony Bennet and Leonard Bernstein and others was Ossie, and in the not too distance background stood the governor of Alabama, George Wallace’s most feared racist law enforcement chief, Bo Connor and his battle-ready GESTAPO. Ossie paused and gazed at the display of force, and at that moment, all of the horrors that Bayard Ruston had prepared us before danced before us. And just as he was envisioning that we would either be shot or beaten or have mad dogs nipping at our genitalia, or sensing more humanely just perhaps being sent to prison forever, Ossie expressing his deepest concern, turned to me and said, tell me, Harry, you don’t snore, do you? just as a reminder, this was the march in which Viola Liuzzo was murdered by the Ku Klux Klan.

It is hard to fathom that we will no longer be able to call upon his wisdom, his humor, his passion, his loyalty, his moral strength to guide us in the choices we have yet to make in the battles that are yet to be fought. But how fortunate we are, how fortunate we were, to have had him as long as we did. How fortunate we are that he has left us as did Paul, and W.E.B. and Malcolm, and Fanny Lou, and Medgar, and Bobby, and Eleanor, for the blueprint of courage that defined them, and is now left for us, and future generations to absorb and implement by speaking truth to power. We can never say, we do not know how, for there are none to guide us, or to inspire us, and tell us how, or help us understand in unshakeable terms that our struggle will succeed, and that justice will prevail, and that our humanity will endure. Thank you, Ossie. Those whose lives you have touched are forever inspired, and we are deeply, deeply grateful.

AMY GOODMAN: Singer Harry Belafonte, eulogizing Ossie Davis at the Riverside Church Funeral.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to the funeral of Ossie Davis at Riverside Church in Harlem with former President, Bill Clinton.

PRESIDENT BILL CLINTON: Ruby, members of the family, reverend and clergy, I — I want to thank you first, Ruby, for inviting me to come today. I had to go to the doctor first. Like Harry said about Ossie, I don’t want to rush this. And so I couldn’t break this commitment. I kept looking at the watch and I thought to myself, this is his funeral — they’ll still be there at 2:00. But I want you to know that I asked — I asked to sit in the back of the church. I would proudly ride on the back of Ossie Davis’s bus. Any day. Dr. Butts said that Ossie could have been maybe was a Baptist preacher. He would have been a very good President of the United States. I have only this to say. Like most of you here, he gave to me more than I ever gave to him. But whenever I saw Ossie and Ruby, I thought, you know, they’re beautiful, and brilliant, and talented. Their warm and they’re friendly and they’re humble. What is it that they are that makes me feel so good every time I see them? And finally, I realized that they were free, and always have been. I never was in Ossie Davis’s presence, not one time, that I didn’t want to stand up a little straighter. You know, speak a little better, be a little more generous. Not very long ago, the great Nina Simone passed on to her. She sang my favorite song of the civil rights movement, “I wish I knew how it would feel to be free.” I wish I could break all of the chains holding me. I wish I could rise like a bird in the sky. I would soar like an eagle when I found I could fly. I wish that you knew how it feels to be me. Then you would see and agree every man should be free. That lesson is what Ossie Davis taught all of us for 87 years. He labored so other people might enjoy that freedom–but his came from inside, from the greatness of his spirit, from the connection to his Maker from the power of his love with Ruby and their family. And I think I can speak for all of us when I say, thank you, God for letting us know it. God bless you.

AMY GOODMAN: Former President Bill Clinton remembering Ossie Davis as we turn now to Ossie Davis’ grandson, Brian Day.

BRIAN DAY: I never knew Ossie Davis like many of you did. I didn’t know the actor, the activist, I simply knew my grandfather. And he was the greatest example of a man that I have ever known. For his greatness, he was so humble. Many people would want me to tell stories about what he had done, and all I could tell them is that he liked Fig Newtons and Chardonnay. He was one of the humblest people I have ever met. He would treat presidents and heads of state the same way he would treat a man on the street who asked for change, or a waiter who was too nervous to say anything. Every time we left the house with grandpa, he made a new friend. I remember once a lady asked, are you Ossie Davis? His only response was, I hope so, because I have his wallet. When I first learned that my grandfather had died, it was the saddest I had ever been, but it’s turns into me feeling so lucky that he was able to affect me and touch me for 20 years. A lot of people have been calling sending emails and things of that nature, and they always ask if there’s anything they can do to help or anything that the family needs. I usually say nothing, but now I personally need something. I need everyone in here to keep Ossie Davis’s legacy alive. I need you to go tell someone who doesn’t know about him about him, so that he will live far longer than last Friday, and far longer than anyone else in this room. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Brian Day, the grandson of Ossie Davis, as we end the highlights of the Ossie Davis funeral today with the granddaughter of Malcolm X. Ossie Davis eulogized Malcolm X after he was assassinated in 1965. This is Attallah Shabazz.

ATTALLAH SHABAZZ: Yesterday at the wake, I sat and I watched the receiving line of loved ones pass you, pass the family, pass your children, and your grandchildren who have to start using different terms and tenses to a heartbeat that’s going to be ever present for you. I know. I heard people say, “Sorry for your loss.” Sorry for your loss. It’s a hard thing to know what to say to someone in the absence. For us a general public will make the adjustment in picture and memory and everything, but for the family, it’s a deep well. It’s too soon to fill it. But I would ask of everybody not to give regrets, not to simply give sympathies or condolences or even say “sorry for your loss” but rather “thank God for the gift.” What a man. Thank you for the presence of Ossie Davis to walk amongst us, that god would bless us so. In our lifetime to have an example of such a man in our existence, and in a time of — where bling is really fun, let us not be distracted by the authenticity of jewels. Excuse me. His kids did so well. Excuse me. I’m proud. I’m really proud that all of you young black men and women in the 1940’s and 1950’s rallied around one another so much so that my sisters and I would have you, Aunt Ruby, the Davises and the Wallaces, the Poitiers, the Suttons, here with such continuity, an unsteady walk, vigils at the hospitals, and ever-present nonetheless, so when we talk about the beauty and the wonder, the strength of Ossie Davis, and we live in an America that is trying to get comfortable with multicultural existence and diversity, let’s hope it does not dilute the strength of that African. Notwithstanding the beauty of the range, but all too often we delete and diminished that particular noun, and before you at 6’2”, strong and black, not without question, before us in the light of the African, there was a Garvey in the light of an African. There was a DuBois in the light of Africa. There was a DuBois. There’s a Robeson in the light of Africa. There’s Malcolm in the light of Africa. There’s King, there’s Fanny Lou Hamer, and the list going on. I say now in the light of Africa there’s Ossie Davis, walked amongst us.

AMY GOODMAN: Attallah Shabazz, the oldest daughter of Malcolm X remembering Ossie Davis at his funeral at Riverside Church.

Media Options