As the American Psychological Association kicks off its national convention, a debate is raging in the mental health community over the role of psychologists in military interrogations. We host a debate with the director of ethics at the APA Stephen Behnke, British medical ethicist Michael Wilks, and renowned psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton. [includes rush transcript]

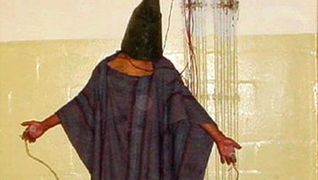

Interrogation techniques used by U.S. military personal on detainees at Guantanamo Bay may amount to torture, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross. Measures reportedly include sleep deprivation, prolonged isolation, painful body positions, feigned suffocation, and beatings.

The role of doctors as so-called behavioral consultants in interrogations is being increasingly scrutinized. Last month we spoke with journalist Jane Mayer about her article in the New Yorker magazine titled “The Gitmo Experiment: How Methods Developed by the U.S. Military For Withstanding Torture are Being Used Against Detainees at Guantanamo Bay.” She told Democracy Now!, “it is becoming clearer that a number of psychologists and possibly, it seems, probably doctors, have been assisting in the interrogation process in Guantanamo and that it has been an abusive process.”

- Jane Mayer, journalist with the New Yorker magazine.

Today on the eve of the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, or APA, we host a roundtable discussion on the position of the APA on the role of psychologists in military interrogations. The APA Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security issued a report last month finding that “It is consistent with the APA Code of Ethics for psychologists to serve in consultative roles to interrogation- or information-gathering processes for national security-related purposes.” The report also affirms that “psychologists have an ethical obligation to be alert to and report any acts of torture or cruel or inhuman treatment to appropriate authorities.”

A leading medical ethicist in Britain published a critique of the APA position in the Lancet, the leading medical journal in England. Dr. Michael Wilks warned that the report is part of a trend of “governments and professional bodies rewriting existing ethical guidance in the service of abuse.”

- Stephen Behnke, director of ethics at the American Psychological Association.

- Michael Wilks, chair of the Medical Ethics Committee at the British Medical Association and author of the article “A Stain on Medical Ethics” published in Lancet medical journal.

- Robert Jay Lifton, leading American psychiatrist and an authority on the psychological causes of war and political violence. He is the author of “The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide.”

- Related Links:

- Dr. Lifton’s article “Conditions of Atrocity” in The Nation magazine

- Dr. Lifton’s articles “American Apocolypse” in The Nation magazine

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today, we’ll host a debate on the position of the American Psychological Association. It’s a debate that’s raging among psychologists around the country. But first, we turn to a conversation on Democracy Now! that we had last month with journalist, Jane Mayer, about her article in The New Yorker magazine. It was called “The Gitmo Experiment: How Methods Developed by the U.S. Military for Withstanding Torture are Being Used Against Detainees at Guantanamo Bay. In this excerpt, she begins by talking about what the Pentagon expects from medical doctors and psychologists at Guantanamo Bay.

JANE MAYER: Well, it’s an area that is very fraught. I think we really don’t know all of the details yet, either, but basically, there are allegations that medical personnel have been assisting in interrogations that are abusive. Ethically, I think pretty much every code of ethics for doctors suggests that they should not be in an interrogation room, particularly if there’s anything coercive or abusive going on. And the same holds, at least according to many people, for psychologists, and so this area is very fraught, very much discussed within the medical community right now, because it is becoming clearer that a number of psychologists and possibly, it seems, probably doctors, have been assisting in the interrogation process in Guantanamo and that it has been an abusive process.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the loophole that involves whether or not they are caregivers?

JANE MAYER: Well, what the Pentagon has done is put out a policy statement that says that no medical personnel will be involved in handing over medical records to interrogators or will be involved in interrogations, so long as they are doctors who are treating the detainees. But that’s the loophole. They have a whole separate category of doctors and psychologists that we’re learning about, which are non-treating medical personnel. And those are very explicitly involved in the interrogation process. And I think that what is of concern is that they seem to be bringing skills from the scientific world into the interrogation room in a way that begs a lot of questions about whether it’s ethical.

AMY GOODMAN: New Yorker magazine reporter, Jane Mayer, went on to talk about the SERE program, which stands for Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape. Military psychologists originally designed SERE to inoculate soldiers against the psychological coercion, abuse and torture that they might be subjected to if they were captured. Again, Jane Mayer.

JANE MAYER: What I found in my reporting was there was indeed a connection, which is that a number of the psychologists who are the people who are major figures in the SERE program and have worked in it for a number of years are actually working and have been working for some time with the behavioral science consultation teams that helped the interrogators that the U.S. has both in the Department of Defense and in the C.I.A.

AMY GOODMAN: Again, we’re talking to Jane Mayer of The New Yorker magazine. Her piece is called “The Gitmo Experiment.” And the level of monitoring, how close it is, how every move, down to the use of toilet paper?

JANE MAYER: Well, that — an interrogator, whose opinions and basically his recollections I was able to go over with very carefully, said that all of the interrogations there are bureaucratized, very, very carefully monitored. There are voluminous notes taken on every detainee. And each interrogation plan is kind of individually devised by the behavioral scientists who are working on it in order to kind of create something that would get at the detainee, particularly the resistant ones, break down their resistance in a very individualized way. So, yes, there was one plan, in particular, that a detainee’s lawyer described to me in which the detainee was told that a psychiatrist had monitored the amount of toilet paper he was allowed. He was only allowed seven squares a day. And that was actually an improvement over earlier when the psychiatrist, according to these sources, had taken away all of his toilet paper.

I mean, The New York Times actually had an interesting case recently where they described a detainee who was afraid of the dark, and so he was purposely kept very much in the dark. There’s another detainee there, I know, who has not been able to see sunlight for a number of years, they only take him out at nighttime. And I don’t know what the situation — what the reason is for that. That is David Hicks. But his lawyer has described that. So each person, each detainee has had kind of a psychological assessment and a plan kind of created for interrogating him, depending on his weaknesses and vulnerabilities.

AMY GOODMAN: You also interview a spokesperson for Physicians for Human Rights. I mean, this is an organization that has been involved in looking at the use in this country of doctors in the death penalty, in being involved in putting people to death. What about how they’re dealing with the use of medical personnel at Guantanamo?

JANE MAYER: Well, they are critics of the Bush administration generally on the human rights record of the administration, and in particular, they are very, very critical of this use of science. They think that doctors and psychologists should not cross this line and be involved in any kind of coercion or abuse. I mean, basically, the ancient code for the medical profession is the Hippocratic Oath and it begins with, first, do no harm, and that the society’s basic feeling about what doctors are supposed to do is for every patient put their welfare first. And I think there have been a number of codes of ethics and legal codes that have developed since the awful experience with the Nazi doctors in World War II since then that have codified the notion that doctors should not do anything to a patient that harms them, should not turn them into experimental subjects without their informed consent and, even if national security is an issue, that the patient’s needs are supposed to come first.

AMY GOODMAN: New Yorker magazine journalist, Jane Mayer, talking about the participation of psychologists in developing interrogation techniques after September 11. Today, on the eve of the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, which is known as the A.P.A., we host a roundtable discussion on the position of the A.P.A. on the role of psychologists in military interrogations. The A.P.A. Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security issued a report last month finding, quote, “It’s consistent with the A.P.A. Code of Ethics for psychologists to serve in consultative roles to interrogation or information gathering processes for national security-related purposes.” The report also affirms that, quote, “Psychologists have an ethical obligation to be alert to and report any acts of torture or cruel or inhuman treatment to appropriate authorities.”

A leading medical ethicist in Britain, who will join us today, published a critique of the A.P.A. position in the Lancet, the leading medical journal in England. Dr. Michael Wilks warned the report is part of a trend of, quote, “governments and professional bodies rewriting existing ethical guidance in the service of abuse.” Today, we’re joined by three people. In our Washington studio, Dr. Stephen Behnke is director of ethics at the American Psychological Association. On the line with us from London is Michael Wilks, Chair of the Medical Ethics Committee of the British Medical Association and author of the piece, “A Stain on Medical Ethics,” published in the Lancet. Also with us on the line from Massachusetts, Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, leading American psychiatrist and authority on the psychological causes of war and political violence. He has written many books, among them, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. But we’re going to begin today in Washington with Dr. Stephen Behnke, director of ethics at the American Psychological Association. Can you talk about the report that was released by the A.P.A., what the stand of the A.P.A. currently is on the role of psychologists in military interrogations? And welcome.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Thank you very much. The Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security said that the psychology code of ethics applies to all of a psychologist’s activities. So whenever a psychologist is acting, the ethics code applies. Now, what that means in this particular instance is that a psychologist cannot exempt him or herself from the code of ethics by saying, well, I am a behavioral consultant or I am a behavioral specialist. The task force rejected that position and said that whenever a psychologist is acting, the ethics code applies. The task force also said that psychologists, when acting within strict ethical guidelines, may support and assist information gathering and interrogation processes.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Stephen Behnke of the American Psychological Association. There is a large debate within the organization right now about the position of the A.P.A. We’re going to go to break, and when we come back, we’ll get response from Dr. Michael Wilks, who is speaking to us from the British Medical Society in Britain and wrote the piece, “A Stain on Medical Ethics.” We’ll also be joined by Robert Jay Lifton.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We continue the discussion about the role of psychologists and psychiatrists in military interrogations. Our guests are Dr. Michael Wilks, Chair of the Medical Ethics Committee of the British Medical Association. He is speaking to us from Britain from the British Medical Society; Dr. Stephen Behnke, director of ethics at the American Psychological Association; and Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Let us go to Dr. Wilks from the British Medical Society, Chair of Medical Ethics at the Committee of the B.M.A. Can you respond to Dr. Behnke?

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Yes. Thank you for inviting me. The reason I wrote the Lancet piece was that the background that we’re very concerned about here in the B.M.A., and I think many medical associations are, is the way in which doctors, psychiatrists, psychologists can buy into a sort of culture that it’s okay, it’s acceptable to use one’s professional skills in the interest of some other higher imperative, in this case national security. And I think it’s very difficult to see how a psychologist who has training in psychological techniques designed to help people with psychological problems, in other words, to put it bluntly, to help heal minds, can in any way regard it as ethically acceptable to be engaged, even at a distance, in training people in techniques that damage minds. And so, when Dr. Behnke talks about working within good ethical practice, my point is it can never be ethical to in any way help advise the military how to damage people’s minds.

And you referred to the Physicians for Human Rights organization; they wrote an extremely long and detailed report very recently about the uses of psychological techniques in interrogation, which quite frankly amount to torture, because they’re designed to destabilize people — so they’re designed to destabilize people so that you will get information out of them, and Jane Mayer, in your piece earlier, described some of those techniques. And my point, bluntly, is it cannot be ethical to engage in techniques, even at a distance, that are designed to damage people’s mentality, when presumably the main purpose of being a psychologist is to heal their wounds.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Stephen Behnke?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, I have a letter from Physicians for Human Rights that was sent to the American Psychological Association, and in that letter that was written by the Executive Director of Physicians for Human Rights, he allows for the possibilities that, in fact, there may be a role for psychologists in interrogation processes that is, and this is his phrase, “quite benign.” So, for us, the question is not whether psychologists may be involved in these processes, it’s how psychologists may be involved in these activities in an ethical manner.

I would also dispute Dr. Wilks’ characterization that the activities are intended to harm. Psychologists have been supporting questioning and interrogation processes for law enforcement domestically for many years, and the purpose of those activities is to gather information, not to harm the subjects of the interrogations.

Finally, I would say in response to Dr. Wilks’ statement about how psychologists should never serve a higher good, I would suggest that, in fact, at times, looking at what a higher good is part and parcel of what psychologists do. In this country, we have what we call mandated reporting statutes for child abuse. At times, when a psychologist has reasonable cause to suspect that a child is being abused, that psychologist has both a legal and an ethical obligation to break confidentiality in the service of a higher good, and that higher good is to protect an innocent child from being harmed. So, it is the case that in their work, in a therapeutic context, psychologists will sometimes serve a higher good.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Michael Wilks?

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Well, yes. And there, Dr. Behnke is talking entirely, as he just said, about the individual doctor-patient or psychologist-client relationship. Of course, I agree with him. If I know one of my patients is abusing a child and there’s a serious risk to that child, I have no obligation to keep confidentiality. But I think we have to see this in the context of what we know is going on. We have had the Schlesinger report, the Fay report, PHR’s own report, a number of other reports, including the Red Cross report, which has only been partially leaked, in which we know that health professionals have been engaged, probably not systematically, but certainly engaged in abuse and probably, if not in torture, at least ignoring torture and in handing over medical records to engage with interrogators. So, for the A.P.A. to talk about benign techniques is, to me, something of a fantasy. We have to deal with what we’re experiencing now.

And people who are detained at Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, many of these people, we have to remind ourselves, are not actually being charged with anything. They’re being held well outside the Geneva Conventions, according to your president’s dictum. Then they have limited access to lawyers. In fact, we know that when four of them returned to the U.K., they were immediately released without any charge. So they are suspects. Now, to treat suspects in this way is grossly unethical. But for organizations to claim that they can only be engaged in research, as the A.P.A. Presidential Code specifically says — it encourages research into the involvement of psychologists in interrogation techniques — those interrogation techniques, in my view, cannot be benign because they’re designed to inflict suffering on people, to destabilize them and to get information out of them. And I think it’s a very, very dangerous game for the A.P.A. to get into some idea that it can always dictate whether its members are engaged in benign psychological techniques when the whole imperative behind the Pentagon involvement in Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib is actually to break people down. So I think that associating oneself with that kind of activity, even at a distance, is very, very hard to justify.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to bring Dr. Robert Jay Lifton into this conversation. He’s been looking at issues like these for more than half a century. If you could weigh in, as you have, on this debate.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, I completely agree with Dr. Wilks. It’s very dangerous to allow yourself as a physician or psychologist to engage in destructive behavior in the name of a, quote, “higher cause.” Of course, I studied Nazi doctors, and when I invoke them now, it’s in no way to equate American doctors with Nazi doctors — that would be wrong — but rather to look at an extreme violation of all views of medical ethics and human behavior, in general, which the Nazis manifested, and to see what we can learn about that extreme violation in connection with relatively lesser violations, but still very disturbing ones.

And central to Nazi doctors’ behavior was what I called socialization to atrocity. It’s the state policy. You embrace the state policy, in general terms, as a Nazi doctor, even if you don’t believe in all the details, and you then give your medical knowledge to the service of the state policy, which in the Nazi case included doctors’ leading role in the killing process, not just experiments. Here, it’s a parallel atrocity-producing situation, as I call it, and that really means that it’s a situation that is so constructed militarily and psychologically that an ordinary person, no better or worse than you or me, can enter into that environment and participate in atrocities. Doctors are particularly vulnerable and psychologists, too, because we are part of what I call the shamanistic legacy. We are the descendants of witch doctors and shamans and are perceived as having some magical influence over life and death that’s very tempting for despotic regimes to embrace and make use of in order to harm people, carry through its purposes and control reality.

So, it then behooves our professional organizations to be very specific and very careful in delineating things that are unethical and that we should not do. To some extent, that exists in various protocols which prohibit doctors from participating in torture, but these protocols have to be brought up to date in relation to the specific context of the current atrocity-producing situation for Americans in Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Stephen Behnke of the American Psychological Association, your response to Dr. Robert Jay Lifton.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, I absolutely agree with Dr. Lifton, when he says that there need to be strict ethical guidelines about what is permissible and what is not permissible. And that is what the American Psychological task force has begun to do in its task force report, to delineate what are the conditions in which a psychologist may engage in these activities in an ethical manner. Also, in responding to Dr. Wilks’ statement, if psychologists have engaged in any activity, and at this point the media reports are long on hearsay and innuendo, short on facts, the American Psychological Association wants the facts. And when we have the facts, we will act on them. And if individuals who are members of our association have acted inappropriately, the A.P.A. will address those very directly and very clearly.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: May I respond to that?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes. Dr. Robert Jay Lifton.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: I have to say that many of the facts are already in. Unfortunately, American physicians and psychologists have been active in interrogation processes at the edge of torture, and I think we have these facts from very reputable international human rights organizations, including the Red Cross. So, I don’t think we have to wait any longer for those facts. The difficulty in the position that Dr. Behnke is putting forward — I mean, I respect his search for an ethical position, but the difficulty in what he is saying is that it encourages what I call a kind of doubling in psychologists. In Nazi doctors, I observed a process I came to call doubling which meant the formation of what is functionally a second self so that the same person could engage in killing in Auschwitz six days a week and then go home to Germany and be an ordinary father or husband.

This is a different kind of doubling we’re talking about here, where the same psychologists can be either a non-healing person, somebody who is consulting in breaking down people through interrogation and torture situations on the one hand, or is also a healer on the other. Sometimes they’re divided into two people, or it may be the same person. But this is sophistry. Intellectually and ethically and psychologically, it’s harmful, not only to the victims, but to the participating psychologists in encouraging an unethical side as being acceptable because it’s in keeping with the particular larger political project of the organization he is serving.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to do a comparison of the positions of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the British Medical Association, and the World Medical Association. Dr. Michael Wilks of the British Medical Association, can you compare them?

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Well, I think that there isn’t any great difference in what we all say about the need for good ethical practice. But I think the problem is that we’re actually looking at something new, because what we have tended to assume, perhaps naively, is that good ethical practice in relation to your individual care of patients is the same — has the same principles attached to it as good ethical practice that you operate as a professional. In other words, as a psychologist or as a psychiatrist or as a medical practitioner. In other words, you know, a doctor is a doctor is a doctor.

And I think what we have been called out by is a recurrence, and it happens to be in the U.S.A. now, but I really don’t want this to be thought of as to be an anti-American comment, because we have seen it in Nazi Germany, we’ve seen it in Chile and South Africa, and I would say also probably in Northern Ireland, the way in which Dr. Lifton, and I have to say Dr. Lifton’s work has been pivotal in our thinking about this, and it’s a privilege to be able to debate with him, but I think that what we have failed to recognize is that administrations will circumvent ethical guidance around individual care and, if you like, pervert it when it comes to the care of populations.

And we have seen that the United Nations codes, the W.M.A. codes and probably our own codes, as well, are inadequate when it comes to saying, you don’t do this. You simply do not do this. You are a psychologist. Because you have signed up to ethical standards to look after people’s minds, you do not get engaged in damaging them, either directly or indirectly.

So, what we’re doing here at the B.M.A. is encouraging the next W.M.A. meeting later this year rewriting of various ethical codes, particularly the declarations of Tokyo and Geneva, to tidy up what we see as a loophole. I think we really thought that this kind of debate was now dead after its recurrence in Germany and Chile and South Africa. And I think one of the most depressing things about this is that we’re now facing exactly the same problem of institutional collusion in unethical behavior, because our own codes don’t actually cover it.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Stephen Behnke.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, I would like to make a point very clearly, and that is the task force report makes very clear that a psychologist would never, under any circumstances, and it would be unethical for a psychologist to have both a treatment relationship with an individual and then to in any manner participate in any type of information gathering or interrogation process in regard to that same individual. So, there is an absolute separation of roles in that regard.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: But what if he —

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Second point —- the second point I would like to -—

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s get a response for a minute from Dr. Robert Jay Lifton on that point.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, yes, I understand that, but it’s the doubling within the particular psychologist. He doesn’t have to be treating a person or seeking to break him down through interrogation. He might be treating other people, or it might be a different psychologist that’s treating other people. It’s that division between the healing commitment and a kind of willingness or encouragement to take part in the breaking down of people that lies in — that really creates what is I call the doubling in the particular psychologist. It doesn’t require that he be treating and breaking down the same person.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Yes. Dr. Behnke is raising a question that nobody would find acceptable.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Wilks.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: That nobody would find acceptable, the idea that you could treat somebody and torture them at the same time. That isn’t the discussion. The discussion is around whether there is a basic ethical imperative as a psychologist to only act on behalf of people in the interests of their benefit, in other words, first do no harm.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Let me — if I may — if I may respond to that.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Behnke.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: In all fairness, the American Psychological Association is very clear that under no circumstances is it in any manner permissible for a psychologist to engage in, to support, to facilitate, to direct or to advise torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment. The American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association issued a joint statement against torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment in 1985. In 1986, the American Psychological Association issued another resolution against torture. So, to even suggest that that would in any manner be permissible is completely out of bounds.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Might I ask a direct question, because I’m really interested to know, could I ask why the A.P.A.’s presidential report then specifically recommends that psychologists should be involved in research into interrogation techniques?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, as I have —- as I have said, psychologists have been working together with law enforcement for many years domestically in information gathering and interrogation processes. We believe that as experts in human behavior, psychologists have valuable contributions to make to those activities. So -—

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: You know, if I may say something here —- it’s one thing to have fine -—

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Robert Jay Lifton.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Fine ethical statements about what doctors or psychologists should not do. When I wrote my piece over a year ago in the New England Journal of Medicine about doctors’ complicity in torture, there were a couple of angry responses from military physicians, saying, 'Look, we have these clear military rules and requirements. These things are prohibited. How you can say this?' Well, the difficulty is that you can have those nice rules, but you don’t have a protocol that speaks to the particular social situation that doctors and psychologists enter, what I called an atrocity producing situation. You don’t speak to a rule that doctors cannot take part in interrogation, and in that way, all of these fine principles exist in the books, but have no immediate power to restrain doctors from that intense psychological situation of adaptation to military policy in which they find themselves. That has to be spoken to in protocols, the socialization to atrocity, which doctors and psychologists are prone to, rather than just these fine principles of not engaging in torture.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: I wonder if I —

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, in fact, if I may —

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Behnke.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: The task force report does speak to the social situation and to the pressures that psychologists are likely to feel in these situations. So, it does directly address Dr. Lifton’s point.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break and then we’ll come back to this discussion about the role of psychiatrists and psychologists in military interrogations. Our guests, Dr. Stephen Behnke, director of ethics at the A.P.A, the American Psychological Association; Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, renowned psychiatrist here in this country; and Dr. Michael Wilks, Chair of Medical Ethics at British Medical Association.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As we discuss the role of psychologists, psychiatrists in military interrogations, we’re joined by the head of ethics at the American Psychological Association, which is about to have its annual meeting. This is a raging debate within the A.P.A. They have just put out a report on the role of psychologists on psychological ethics and national security. We are joined by Dr. Michael Wilks, Chair of Medical Ethics at the British Medical Association. As well, we are joined by Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, who’s a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, among his books, The Nazi Doctors. As we talk about psychologists’ role, I wanted to ask, Dr. Stephen Behnke, with the reports out of Bagram, out of Abu Ghraib, out of Guantanamo, about what has happened to detainees, about information that is gathered by psychologists, perhaps about a prisoner’s fear of the dark or other concerns, sharing that with an interrogator, whether or not the psychologist is then in the room at the time of the interrogation. Has this led you to raise more questions and deal with this issue of whether psychologists should be involved at all with these interrogations?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, again, I would say that for us, the question is not whether psychologists may be involved. We believe that there is an ethical role for psychologists to play. The question is “What are the ethical boundaries within which psychologists must remain when they are engaged in these activities?” Certainly, if it is the case that individuals have behaved unethically, the American Psychological Association has an ethics committee that will respond to that situation through our process of adjudication.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Michael Wilks.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Well, yes. I think that’s the core of it, as Dr. Behnke says. It’s not a question of, as he says, whether psychologists should be involved, but it is how. And I suppose my argument is, well, the how is impossible to answer, because they shouldn’t be involved. And if they are involved, the perfectly legitimate desire to find ethical boundaries is actually a futile search, because those boundaries will not be identifiable, and if they are, even if they are identified, they’ll be crossed by individual psychologists working outside good ethical principles.

I just — if I may, just to widen this a little bit, and if you don’t want me to do this, just stop me, but I’m calling from the British Medical Association building in the middle of London. And five weeks ago, a large bus with a suicide bomber in it exploded directly outside our building, covered the whole of the side of our building with human remains. People died in our building from their injuries. And the people who did that, including the other three bombs that went off on the 7th of July in London, were British. They were British Islams — Islamic believers. They were not from Afghanistan or from Pakistan or from Iraq or Iran. They were people who had lived here for a long time and grown up here. And they were, as we understand it, from the people who were arrested who failed to set off bombs two weeks later, profoundly opposed to the war in Iraq.

Now, I don’t blame any particular individual or institution for the war in Iraq, but I do think that we have a responsibility to think how if we contribute to a climate of abuse, even very indirectly, even perhaps even with the best of motives, which is the higher authority, we will continue the hatred that some people feel for institutions like ours, the institution of democracy in this country, the way in which we have been implicated in the war in Iraq. So I think it’s terribly important to take a big global perspective on this and ask ourselves whether our own difficulties with our ethical position can contribute to a climate of resentment. And I think that, you know, from the very, very U.K. perspective, and I hope a reasonably compassionate one, for a country to occupy another country and then mistreat it its citizens on a suspicion of being terrorists, even not a proof, outside the law, outside the Geneva Conventions, is a very, very provocative thing to do and will produce the sort of result we saw here in London just a few weeks ago.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: And if I may add to that —

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Robert Jay Lifton —

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: If I may add to that, the kind of war being fought affects psychologists and psychiatrists and affects very much the sort of discussion we’re having. The war in Iraq is a counter-insurgency war, with great confusion about who the enemy is. There is an undue stress put upon interrogation. It takes on an almost magical quality, as though we can solve what is really an un-winnable war through enough interrogation by finding out who the, quote, “bad guys” are, and that creates the atrocity-producing situation I described. So it’s a particular kind of war that renders psychologists and psychiatrists particularly vulnerable to this sort of misbehavior, and that has to be very much part of our equation.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Stephen Behnke, the task force —

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: If I could — could I respond just for a second? I would just like to extend our sympathy to Dr. Wilks, and you know, to his colleagues. It’s a terrible tragedy what happened in London, and certainly, the, you know, British people were very sympathetic in support of after the terrible events here on September 11 of 2001. So, I just wanted to make that statement.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Thank you.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: I think that Dr. Wilks is referring to a kind of social and historical dynamic in which the aggressive political and military behavior over which doctors and psychologists have little control interacts with extreme behavior on the part of those who would attack us in this continuing dynamic, and the issue of doctors and psychologists and what they do is very much in the context of this ongoing dynamic. And we should see that the aggressive measures that we may take militarily, such as the Iraq war, affects the situation on the ground, as it’s said, and the pressures that are put on doctors and psychologists. If we don’t look at this larger dynamic, we’re really blinding ourselves to the kind of pressures that are put on doctors and psychologists.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, I would agree with Dr. Lifton’s statement. And again, I would note that the task force report is very sensitive to the social situation. It does call for research, and one of the calls for research is on the effects of involvement in interrogation activities on the interrogators themselves. And the task force felt that that research was particularly important to explore ways that we could ensure that interrogation processes remain within ethical guidelines.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Stephen Behnke, when it comes to the Geneva Conventions, A.P.A. ethics standards, as well as law, where does the A.P.A. stand on international law, when it is in conflict with U.S. law? And what about the ethics of the A.P.A., the ethics standards?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: Well, the ethical standards are that psychologists obey the law. Psychologists do not violate the law. Now, the task force report discussed both U.S. law and international law, and the task force makes a very clear statement that international law, international standards are critical. The task force states that psychologists have an absolute ethical obligation never to violate any United States law. And then, in addition, the task force said that psychologists must adhere — and they used four words to describe psychologist involvement: safe, legal, ethical and effective.

AMY GOODMAN: And if U.S. law conflicts with international law, where you have, for example, Alberto Gonzales, at the time the White House Chief Counsel, saying that the prisoners — that the Geneva Conventions do not apply to those being held at Guantanamo. What does a psychologist do then, involved in the interrogation, saying they’re not protected by the Geneva Conventions?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: A psychologist’s involvement may never, according to the task force report, engage, facilitate, support any activity that constitutes torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and it must be safe.

AMY GOODMAN: Robert Jay Lifton.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, I think that’s still risky ground for the psychologist to be in, because, as you say, you may ask him or her to study interrogations and the effect of interrogations on the interrogator, but the psychologist is not in a position to control military policy, and where national and military policy steps over into the realm of torture, even by legal fiat, as you have been saying, then the psychologist is in a situation of contributing to that process in the name of trying to keep it humane.

There’s something else I wanted to say, just it seems appropriate here, perhaps in an indirect way. When I went to study Nazi doctors, I had to clear my research with the Yale Committee on Research with Human Subjects. I was then at Yale, and this was a post-Nuremburg principle that anybody doing research with human subjects had to be sure to do no harm, not to harm them in any way, and also to maintain their confidentiality. I thought this was very ironic, because the principle derived from what these people whom I was studying had actually done, the Nazi doctors. And yet, as I thought about it, it seemed just right. I was being asked to maintain humane standards, while looking to study people who had done the opposite.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to be wrapping up this discussion, so I do want to get to the nut of it. Since the American Psychological Association is having their annual meeting, I know this is going to be a main source of discussion and debate. The American Psychiatric Association says that mental health professionals should not engage in interrogation, should not be involved in any way. The American Psychological Association does not agree with this. While you recognize, Dr. Stephen Behnke, that there have been problems, for example, at Guantanamo, the A.P.A. hasn’t taken the position that psychologists should stay out of this. Of course, a number of people on the American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force are military psychologists, and one of the leading people is one of those very involved with Guantanamo. Why not just say stay out entirely? What’s the benefit of being a part of this?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: We believe that psychologists are experts in human behavior, and that as experts in human behavior, psychologists have important contributions to make to information gathering and interrogation processes when they do so within strict ethical guidelines.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think the military psychologists have succeeded in doing this at Guantanamo?

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: I don’t know. I don’t have firsthand knowledge of what went on at Guantanamo. I know that the A.P.A. very much wants the facts, and that when A.P.A. has the facts, we will act on those facts.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: You know, we have left one thing out of this conversation —

AMY GOODMAN: We have 30 seconds.

DR. MICHAEL WILKS: Okay.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: I want to say very briefly, the psychologist and the doctor are caught between their healing function and their responsibility to military policy, when you are in the military. I remember this when I — from the time I was in the military. And where military policy oversteps the bounds into torture, the psychologist is under enormous pressure to do that, and all of that has to be taken into account when we talk about the facts. I have to say the facts are in, and we have to act on them.

AMY GOODMAN: On that note, we have to wrap up. I want to thank you all for being there. We’ll get input from people at our website, DemocracyNow.org. Dr. Stephen Behnke of the A.P.A., Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, and Dr. Michael Wilks of the British Medical Association, thanks for joining us.

Media Options