This weekend marks the sixtieth anniversary of the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. William Laurence, the New York Times reporter who covered the bombings, was also on the US government payroll. Journalists Amy Goodman and David Goodman call for the Pulitzer Board to strip Laurence and his paper, The New York Times, of the undeserved prize. [includes rush transcript]

Amy Goodman and her brother, fellow journalist David Goodman, have co-authored an opinion piece in the Baltimore Sun today called Hiroshima Cover-up, challenging the New York Times coverage of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 60 years ago.

They are filing an official request with the Pulitzer committee to strip New York Times correspondent William Laurence of the Pulitzer he was awarded for his reporting on the atomic bomb. Laurence was not just a reporter for the Times, he was also on the payroll of the US government. He wrote military press releases and statements for President Harry S. Truman and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, all the while faithfully parroting the line of the US government in the pages of the New York Times. His reporting was crucial in launching a half century of silence about the deadly lingering effects of the bomb. It is high time, the Goodmans say, for the Pulitzer board to strip Hiroshima’s apologist, William Laurence, and his newspaper, the New York Times of their undeserved prize.

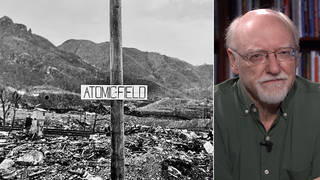

On August 6, 1945, the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima; three days later Nagasaki was hit. General Douglas MacArthur promptly declared southern Japan off-limits, barring the press. Over 200,000 people died in the atomic bombings of the cities, but no Western journalist witnessed the aftermath and told the story. Instead, the world’s media obediently crowded onto the USS Missouri off the coast of Japan to cover the Japanese surrender.

One reporter defied the ban and took a train for thirty hours to Hiroshima, the first Western reporter to arrive on the scene.

- Wilfred Burchett, journalist who wrote the first report from Hiroshima.

- David Goodman, independent journalist and co-author of “The Exception to the Rulers.”

Related links:

- The Hiroshima cover-up, an Op-Ed in the Baltimore Sun by Amy and David Goodman

- Hiroshima Cover-up: How the War Department’s Timesman Won a Pulitzer, a chapter of Amy and David Goodman’s book, “The Exception to the Rulers: Exposing Oily Politicians, War Profiteers, and the Media that Love Them”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today on the program, we’re going to take a look at some of the stories the U.S. government hoped would never see the light of day. We’re going to talk with the son of George Weller, a Chicago reporter, who was the first reporter to make it to Nagasaki, but his piece never made it into his newspaper, stopped by U.S. military censors. And we’re going to talk about William Lawrence’s coverage of this period, of this era. But I wanted to start with talking about the coverage by another reporter. His name was Wilfred Burchett, an Australian reporter who defied the U.S. military saying that the whole area of southern Japan was off limits and took a train for 30 hours to Hiroshima. He actually describes in his own words, and we’re going to go to that recording, of Wilfred Burchett. He describes in his own words his reaction when he made it to Hiroshima and what happened when he got there. Let’s take a listen.

WILFRED BURCHETT: I went to a hospital, which had survived in the outskirts of the city. These people were all in various states of physical disintegration. They would all die, but they were giving them whatever comfort could be given until they died. And the doctor explained that he didn’t know why they were dying. The only symptoms they could isolate from a medical point of view was that of acute vitamin deficiency. So they started giving vitamin injections. Then he explains where they put the needle in, then the flesh started to rot. And then, gradually, the thing would develop this bleeding which they couldn’t stop, and then the hair falling out. And the hair falling out was more or less the last stage. And the number of the women who were lying there with sort of halos of their black hair which had already fallen out. I felt staggered, really staggered by what I’d seen. And just where I sat down, I found some lump of concrete, I remember, that had not been pulverized. I sat on that with my little Hermes typewriter, and my first words, I remember now, were, “I write this as a warning to the world.”

AMY GOODMAN: And that is an excerpt of a documentary by Andrew Phillips called Hiroshima Countdown, Wilfred Burchett, the reporter who made it into Hiroshima, made it to the hospital, saw the devastation. His report appeared in the London Daily Express and rocked the world. It certainly rocked the U.S. War Department. Well, that’s one reporter’s story. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: That’s the story of a reporter who did get his story out, but David Goodman joins us from a studio in Burlington, Vermont. Can you tell us about William Laurence, The New York Times reporter, who won a Pulitzer for his coverage of the dropping of those bombs?

DAVID GOODMAN: Sure. William Laurence was — had immigrated to the United States from Lithuania in the 1930s, at a time when actually The New York Times was laying off reporters, due to the Great Depression. They asked Laurence to become both the newspaper’s and the nation’s first dedicated science reporter. Laurence was — became fascinated with atomic power and atomic weapons and was an ardent supporter of atomic power in the articles that he wrote throughout the 1930s, and into the early 1940s. This is probably what caught the attention of the War Department.

In the spring of 1945, a remarkable meeting took place secretly at the headquarters of The New York Times in Times Square in New York City. General Leslie Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, which was the name of the program that was developing atomic bombs for the U.S. military, came to Times Square to The New York Times and met secretly with Arthur Sulzberger, the publisher of The New York Times, the Editor-in-Chief of The New York Times, and William Laurence. At that meeting, he asked Laurence if he would become a paid publicist, essentially, for the Manhattan Project. So, while simultaneously working as a newspaper reporter for The New York Times, he would also be writing essentially propaganda for the War Department. Officially he was asked to put in layman’s terms the benefits of atomic weapons and the development of atomic power. Other New York Times reporters were unaware of this arrangement, this dual arrangement where he was being paid by both the government and the newspaper and, in fact, were somewhat mystified when Laurence began taking long leaves of absence.

Well, the government’s investment in Laurence paid off in spades because he was rewarded for his loyalty. He was also writing — ended up writing statements for Secretary of War Stimson and for President Truman himself. He was rewarded by being given a seat in the squadron of planes that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. I’ll read to you a little excerpt of Laurence’s dispatch. In general, his writing — well, these days journalists would call it purple prose, but it was often imbued with these messianic themes about the potential and power of atomic weapons.

Here’s what he had to say in describing the bombing of Nagasaki. This bombing is thought to have taken about 70,000 to 100,000 lives. Laurence recounted, quote, “Being close to it and watching it as it was being fashioned,” he’s speaking here of the atomic bomb, “into a living thing so exquisitely shaped that any sculptor would be proud to have created it, one felt oneself in the presence of the supernatural.”

Now, Laurence went on to write a series of ten articles about the development of the atomic bomb. This is — this and his reporting about the Nagasaki bombing won him the 1946 Pulitzer Prize in reporting. He seems to have been completely unashamed and unrepentant of what was clearly an egregious conflict of interest by any of the most basic canons of journalism ethics. Laurence later wrote in his memoirs about his experience as a paid publicist for the War Department. He wrote, quote, “Mine has been the honor, unique in the history of journalism, of preparing the War Department’s official press release for worldwide distribution. No greater honor could have come to any newspaperman, or anyone else for that matter.”

AMY GOODMAN: David, I think it’s instructive, the effects of this reporting. I mean, on the one hand, you had someone like Wilfred Burchett on the ground, talking about — he didn’t even have the words to describe. He talked about “bomb sickness.” He talked about “atomic plague.” And then you have Laurence’s front page story, September 12, 1945, “U.S. Atom Bomb Site Belies Tokyo Tales: Tests on New Mexico Range Confirm that Blast and Not Radiation Took Toll.” This, after William Laurence, while he didn’t go to Hiroshima, was taken by Leslie Groves, the general in charge of the Manhattan Project, that was responsible for the bomb, took Laurence and other reporters to New Mexico to counter what the War Department, what Groves was calling Japanese propaganda of the effects, the deadly effects of radiation.

DAVID GOODMAN: And, in fact, Laurence knew better, because having observed the Trinity test, the first explosion of the atomic bomb in the deserts of New Mexico, he knew that Geiger counters had spiked around the area of the bombing long after the actual bomb itself. In fact, an interesting footnote to this whole encounter is that when Laurence was brought by Groves in this effort, as Amy describes, after Burchett’s article came out, which was a total public relations fiasco for the U.S. government, having Burchett talk about this atomic plague, the General Groves’s driver stood in the center of the crater where the Trinity tests went off as a way to kind of boast that there was nothing wrong there. He later died of cancer, and the War Department gave him a pension, a military disability pension, as a recognition of the fact that he was, in fact, poisoned with atomic radiation on that trip where he brought Bill Laurence to dispute Burchett’s claims.

JUAN GONZALEZ: David, also, this whole issue of whether civilians died of the blast or radiation, the military knew well ahead of time the dangers of radiation because there was a 1943 memo to Leslie Groves from scientists in the Manhattan Project that’s been used often by the anti-depleted uranium activists. It was declassified 30 years later, where it specifically talked about the memo, titled “Use of Radioactive Materials as a Military Weapon,” talking about the use of even low-level radiation. Just quoting from the memo, it says, “In order to deny terrain to either side at the expense of exposing personnel to harmful radiation,” and it goes on to say, “areas so contaminated by radioactive material would be dangerous until the natural decay of the material took place, which could take weeks or even months.” Of course, we now know it could take hundreds of years. And it goes on to say that 'no effective protective clothing for personnel seems possible, but the average — and no decontaminating methods are known.' So, that the army was well aware in 1943 of the enormous potential for radiation dangers to civilians and military personnel as a result of the use of radioactive weapons, not just the power of the blast itself.

DAVID GOODMAN: Well, that’s right. And this debate has had ongoing significance that far outlasted World War II. Laurence was essentially putting out the official government narrative, which is that atomic radiation is not harmful, is not a major byproduct of the nuclear weapons program. You know, it’s only the blast that has essentially a very short impact. The reason that this has importance is that for really a half century, this narrative became the government’s response to all protests against nuclear power, the nuclear weapons programs of the 1950s and 1960s and the Cold War. So, Laurence essentially set the table that the government was to occupy for the next half century as they disputed any attempt to rein in, you know, the rapid acceleration of nuclear weapons and power programs.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, David, thanks very much for joining us. Again, David and I will be filing a formal petition request to the Pulitzer committee next week on the anniversary of the dropping of the bomb on Nagasaki for the Pulitzer to be pulled from The New York Times and William Laurence, for honoring him with this undeserved prize, the man who was not only on the payroll of his paper, The New York Times, but on the payroll of the U.S. government.

Media Options