Related

Guests

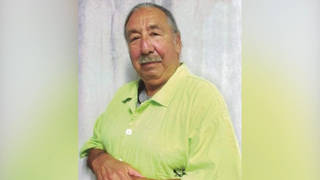

- Yuri Kochiyamalongtime civil rights activist, interned at a U.S. concentration camp during World War II, friend of Malcolm X and with him as he died. Yuri Kochiyama is the author of Passing It On: A Memoir.

It was 41 years ago today when Malcolm X was gunned down in the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. Yuri Kochiyama cradled his head as he lay dying on the stage. Kochiyama’s activism began after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, when she and her family were held in an internment camp along with more than 100,000 Japanese in the United States.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Forty-one years ago today, on February 21st, 1965, Malcolm X was shot dead as he spoke at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. He had just taken the stage when shots rang out, riddling his body with bullets. He was 39 years old.

Malcolm X’s longtime friend, activist Yuri Kochiyama was at the ballroom that day to hear Malcolm X. After he was shot, she rushed to the stage and cradled Malcolm’s head in her arms as he lay dying. Today we’ll hear Yuri Kochiyama talk about that fateful day and speak about the longtime activism in her own life.

For over 40 years, Yuri Kochiyama has championed civil rights, protested racial inequality and fought for causes of social justice. Her story begins during World War II. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Yuri’s parents were forcibly removed from their home by the U.S. government, held in internment camps with 120,000 other Japanese and Japanese Americans. While at a camp in Arkansas, Yuri came face to face with the segregation of the Jim Crow South. She immediately saw the parallels between the oppression of Black people and the treatment of Japanese in America.

In 1960, Yuri and her husband Bill Kochiyama moved into a housing project in Harlem. Yuri became involved in the civil rights movement and was part of the major struggles of the 1960s and ’70s. She especially supported the Black liberation struggle and the work of the Black Panther Party. In 1977, she took part in the takeover of the Statue of Liberty to bring attention to the struggle for Puerto Rican independence. In the ’80s, she and her husband led the successful fight to gain reparations for people of Japanese descent who had been imprisoned during World War II.

I got a chance to interview Yuri Kochiyama in the studios of Link TV just a few weeks ago. She began by talking about this day, 41 years ago, the day Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, New York.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: The date was February 21st. It was a Sunday. Well, prior to that date, I think that whole week there was a lot of rumors going on in Harlem that something might happen to Malcolm. But I think Malcolm showed all along, especially around that time, that there were rumors going on. He was aware, because there were things even in the newspaper, that there was some, I think — I don’t know if it was a misunderstanding or just disagreeing about some things that Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm were talking about. They were personal things. But Malcolm was aware that Elijah seemed to be feeling a little, what would be — oh, I’m so sorry that I’m messing this up — but on some very personal issues, there was disagreement between Elijah and Malcolm, and I think there was even talk that was going on. And after the assassination, however, many Black people felt it could have been by people who had infiltrated or that the police department and FBI may have actually planted them in the Nation of Islam.

AMY GOODMAN: Describe that day. Malcolm came out on the stage, but first he was introduced by someone else. You were sitting in the audience? Where were you?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: No. He was sitting in the little room right next to the stage. And Brother Benjamin was doing the speaking. But everyone noticed that even the guards seemed a little upset, and it was because they said that those who were invited to speak that day, that none of them showed up. And, of course, the crowd in there, about 400 people, realizing something was amiss, did feel that something was going wrong.

AMY GOODMAN: You mean that speakers were invited who didn’t show?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Mm-hmm.

AMY GOODMAN: Where were you sitting?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: I think about the 10th — equivalent to about the 10th row from the podium and almost right across — well, in the middle, where the two guys got up and said — one of them yelled, “Take your hands out of my pocket!” When everybody started just looking at them, the two guys. They were, like, fighting.

AMY GOODMAN: They had stood up as Malcolm X was speaking, very close to the beginning of his speech.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes, he was just going to speak. And Malcolm said, “OK, brothers, let’s just break it up.” But what happened was, it seemed to suck in all his guards closer to what was happening. And then —

AMY GOODMAN: A kind of diversion.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: The diversion, right. Everybody was looking there. Because we were all watching the two guys in the audience, and everybody was watching, and the guards themselves moved from their post. They’re supposed to be protecting Malcolm. Well, Malcolm first said, “OK, now, let’s break it up.” But because Malcolm had left the podium, he was just a perfect target to be shot. And I don’t know if it was two or three men, right in front, went up and started shooting. Well, by that time, the whole place was chaotic. I mean, people were chasing — some of them chasing after those two guys, and people were yelling and screaming, and others — because they let women and children in at the very end, the decision. The kids were — could be crying or just running to get near their mother, and mothers were trying to shield the kids. And I guess the two guys who did the — what was the word you said?

AMY GOODMAN: The diversion?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Diversion. They shot a few times, you know, not to hit anyone, but just, I think, to make the place look even more chaotic there. And Malcolm had told his men, especially the very close Muslims, not to bring any arms, that they didn’t want to frighten the women and children. And so, no one was supposed to bring anything, but one Muslim, and I think thank goodness that one did have a gun, and he’s the only one that shot one of the people who came to assassinate. If he wasn’t there with a gun, I think they would have all fled. And then, anyway, you know the three men who were charged, none of them were even there, and they proved it at the end.

AMY GOODMAN: So, when Malcolm was shot and he was laying on the stage, you ran up?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes, because I saw a young brother pass me, and he seemed to know just where to go or how to get up on the stage. And he acted just like — what do you call it? You call it, not a guard. Well, like one of Malcolm’s security anyway. And he went up, and I followed him. And he went to the back, and he pulled the curtains to see if there was anyone in the back. And at that time, I mean, Malcolm had fallen straight back, and he was on his back, lying on the floor. And so I just went there and picked up his head and just put it on my lap. People ask, “What did he say?” He didn’t say anything. He was just having a difficult time breathing.

AMY GOODMAN: What did you say to him?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: I said, “Please, Malcolm, please, Malcolm, stay alive.” But he was hit so many times. Then a lot of people came on stage. They tore his shirt so they could see how many times he was hit. People said it was like about 13 times. I mean, the most visible is the one here on his chin. He was hit somewhere else in the face, and then he was just peppered all over on his chest.

AMY GOODMAN: Betty, his wife Betty Shabazz, was there with the children.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes. At the very end, he called her. He had told her before not to come, because he was afraid something was going to happen. Then, at the end, he changed his mind and called her and said, “Come, right away. They’re almost starting.” And he said, “Please bring the children. There’s nothing to worry about.” And so she brought them. They had four children, and she was pregnant. And, you know, shortly after, she had two more.

AMY GOODMAN: She also came up on the stage as Malcolm lay there dying?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did you do then?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: When someone told me to go to the side room, and they handed me, you know, a milk bottle and the youngest child, and so they just said, “Feed the baby.” Betty was right there with Malcolm.

AMY GOODMAN: Yuri Kochiyama, remembering the Malcolm X was assassinated at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, New York, as she sat cradling his head. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. We’ll return to Yuri in a moment.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: John Coltrane’s “Blue Train,” here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we return to our conversation with longtime civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama. Forty-one years ago today, she held the head of Malcolm X in her arms as he lay dying after being shot at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem. She first met Malcolm X several years earlier in a Brooklyn courtroom. I asked her to talk about that day.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, I’ll never forget that day. I mean, it was unexpected, even though Malcolm could show up anywhere, you know, at any time and wherever his people are. And, well, all of a sudden, someone walked into the foyer, the first floor of the courthouse in Brooklyn. And all the young kids — they were all Black — they were all running downstairs to the foyer, and here was Malcolm coming in through the front door. No guards. He was there just by himself. I was quite surprised, because it was a dangerous time for him. And all of the kids, they were maybe between 17 and 25, that age, and they were such energetic kids who — they really, like, mobbed him with admiration. Everybody wanted to shake his hands.

And as I watched, about 25 yards away, I felt so bad that I wasn’t Black, that this should be just a Black thing. But the more I see them all so happily shaking his hands and Malcolm so happy, I said, “Gosh darn it, I’m going to try to meet him somehow.” And so, I kept getting closer, and I said, “If he looks up once, I’m going to run over there and see if I could shake his hand.” And so, that’s what I did.

There was a time where — maybe he didn’t look up, but I may have just thought he did or wished he did. And so, then I yelled and said, “Malcolm, can I shake your hands, too?” because all these young people were. And he said, “What for?” And I didn’t know at first what to say. “What for?” I said, “Because what you’re doing for your people.” And he said, “And what am I doing for my people?” Now, I thought, “What would I say to that?” And so I said, “You’re giving directions.” And then, he just changed and said — he came out of the center of that, you know, where everybody was there, came out, and he stuck his hand out. So I ran and grabbed it. I couldn’t believe that I was shaking Malcolm X’s hand. And I was just so sorry that my son, who was 16, who wanted to come so much, but he had an exam in high school, and he didn’t think he could miss that exam, so he missed seeing Malcolm then. He met him later.

AMY GOODMAN: You were there because people — you were among hundreds who were arrested, protesting for jobs for Puerto Rican and Black construction workers?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: So that started your relationship with Malcolm X. It was just really a month before John F. Kennedy was assassinated — would be assassinated in Dallas. October 16, 1963 —

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — was the day that you met him.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Right. October 16th is when I met Malcolm. And —

AMY GOODMAN: And JFK was killed on November 22nd.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: He was killed — yeah, John Kennedy was killed on November 22nd.

AMY GOODMAN: But for the next two years, you would meet with Malcolm regularly. Can you talk about the meetings, the sessions that he had that you would attend?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, they had regular meetings, you know. But it seems like Elijah and Malcolm’s problems were getting a little more serious, and I think because FBI played a role in it, and, of course, they knew which ones of the people in NOI may have had some kind of ill feelings against him.

AMY GOODMAN: Nation of Islam.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Mm-hmm. And things got more serious. There were more articles in the newspaper, and everyone knew that Malcolm’s life was in danger. But also, about that time, I didn’t realize ’til you said right now, that Kennedy was killed only two months?

AMY GOODMAN: Only a month after you and Malcolm X first met.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Only a month after. Oh, because it was November.

AMY GOODMAN: Right. It was the last two years also of Malcolm X’s life, 1963 to 1965, when he was assassinated, as well.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: You received — Malcolm X wrote you postcards through his trip through Africa and his journey to Mecca.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: What did he write to you in these postcards?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, he sent 11 and from nine countries. There were two countries he went twice. But at the time that he went to Africa, all the major African conferences were happening. Two were even happening in England. And Malcolm went to all of these, and, of course, all the most progressive presidents of African nations were at these conferences. So he got to meet almost all the top ones. I mean, there was Ghana’s Nkrumah or Tanzania’s [Nyerere]. I can’t even think of all of them, but he met about 11 of them, and they were as excited to meet him.

He wanted to learn all about the different countries in Africa. And the Africans and he talked about the colonization that took place. Well, it could have happened from even as early as the 1600s, but it was mostly 1700, 1800. And the big day that we’ve got to remember is, I think, 1885. That was where all those European countries took over African countries. What was the name of that? Gosh, I would forget the name. Wait. It might come back to us.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let me ask you about this. When Malcolm came back, he was also talking about an expanded attitude about human rights, something he had talked about before, as well. Not so much civil rights, but the rights of African Americans to be fully equal was an issue of international human rights.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Oh, yes. And that’s why Malcolm thought that this civil rights thing was really nothing, because African people don’t have to wait 'til some president of another country, even United States, would give civil rights. I mean, Africans already have human rights. And he felt, too, that it was too narrowed down when they would be using words that they were just fighting for civil rights. And I think what was so wonderful is that Malcolm taught his group, American — well, Black Americans here, about the history of Africa, where they became colonized, and then he told the people in Africa what was happening here, how Blacks were treated, and that many of the African young people didn't even know anything hardly about slavery, because this country never told them anything.

AMY GOODMAN: Yuri Kochiyama, he also came to your house to meet with survivors of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima/Nagasaki: hibakusha, the survivors.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes, right.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about that?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, we were all so happy, I mean, especially Japanese Americans and even other Asian Americans, that Malcolm would be interested. But Malcolm was interested in every group, and especially when he would hear the kind of harassments and all the negative things that always seemed to be happening to people of color. And he knew about Asian history so well. We couldn’t believe it.

I mean, I wasn’t sure he was even coming, so I didn’t know if I should put out leaflets, but the word went around, I guess, and I couldn’t believe that the day that Malcolm came, our house was packed. Every bedroom — we have four bedrooms — and the kitchen and the hallway. And we had Blacks and whites and Puerto Ricans or anyone else, but they were mostly all activists. Now, there were, as I say, Blacks, but there were none of Malcolm’s people — no nationalists, no Muslims, no radicals. I mean, the Blacks were mostly all civil rights activists. The whites, of course, were also.

At first, people didn’t know whether they should go up to him and ask if they could shake his hand. They didn’t know if he might even be very cold to them, because their ideology was quite different from Malcolm. But as soon as the first person went up to see if he would shake anyone’s hand, and Malcolm was so warm to the person — I think the first one was white — that everybody started going to Malcolm, and he was so wonderful to each one. He was very warm to them. And he really — you could see he acted like he was so glad to meet all these people. But then, because it would take too long if everybody would come in from the other rooms to shake his hand —

AMY GOODMAN: But he then heard the testimony of the hibakusha, of the survivors?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Oh, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s why he had come, to meet —

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: — this delegation that had come from Japan.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Right. I mean, for months before, they said they were coming, and there was about 40. But he had told us 40 people in your little room, he said, no, they — just limit it maybe to the ones who were the reporters or writers. And so, the other Japanese who were not, they felt very disappointed and hurt. But their writers came. There were only three, because the writers themselves said they didn’t want any translation, because each time then, it would take time. Malcolm would say a few words. Then everybody has to keep quiet, while somebody interprets, and it would keep going like that. So they said no translators. And it went well, I think better, because he didn’t have to stop and have the translation. And —

AMY GOODMAN: We don’t have much time, Yuri Kochiyama, but I just wanted to end, as we talk about Japan and World War II, by talking about your own experience and what ultimately politicized you, and that was what happened to your family on the day that Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. Where did you live? How old were you then?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: I lived in San Pedro, California, which is, you know, on the west side of California, and it’s where many, many Japanese lived. Well, the Japanese were mostly all living on the West Coast: Washington, Oregon, California and parts of Arizona. And that’s the number one war zone. But immediately, the newspaper headlines were “Get the Japs Out!” and people like — who’s the guy, that general on the West Coast, the top one, the top general? I can’t think of his name. He said, “The only good Jap is a dead Jap.” And, anyway, not just the newspaper headlines, but there were signs all over: “Get the Japs out! Get the Japs out!” And —

AMY GOODMAN: You were a teacher? You were teaching that day that Pearl Harbor was bombed?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: No, no. I had just finished junior college. No, I wasn’t teaching. But I was teaching Sunday school. And I had been teaching about a year and a half. It was a place where I felt very comfortable. But that day, when I went in, I could just feel something was different. And, of course, it’s because that’s all people were thinking about is —

AMY GOODMAN: Were you the only Japanese American at the Sunday school?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Oh, yeah, mm-hmm. It was really what’s called a white church. So, I took all the kids home, as I usually do. They pack in the car, sit on top of each other, and I take about 10 of the kids home. And then, when I came home, I was — just made it home. I knew my father had come back from the hospital, so I came back early, too. And just a few minutes later, three tall white men, I could see through the window. They were right there at the door.

And so I went there to see who they were. And they all, you know, put their — like a wallet out, which had the FBI card. And they said, “Is there a Seiichi Nakahara living here?” I said, “Yes, that’s my father.” They said, “Where is he right now? We need to see him.” I said, “Oh, he’s sleeping in bed.” I said, “He just came home.” I don’t know if it was that morning or the day before, he came home from ulcer surgery. And they said, “Well, where is he?” And I pointed to one of the bedrooms. And they went in and got — it was done so quickly, it didn’t even take a half of a minute, I don’t think. And I didn’t dare ask a question. They were going out the door immediately. And then, I just called my mother, who was right down the street, to say, “Come home quick. The FBI just came and took pop.” And —

AMY GOODMAN: He was the first person, Japanese American, arrested after the bombing of Pearl Harbor?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: That’s what we heard, but I don’t know if it was the first. They could have been doing all over, but I think he was one of the first, because the first — in 24 hours, I didn’t — I don’t think they were — well, they did find the Japanese still very quickly. So I’m sure they had a list. And —

AMY GOODMAN: What was his job, that they went after him?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, he was in the fishing business. That’s why it hit all fishermen, because they knew then that the fishermen knew the waters. And if the Japanese ships got close enough, would the Japanese fishermen in America help the Japanese? But, actually, I tell you, the Japanese Americans and even the Isseis, first generation, who could not become Americans, they were so American. And yet, the hysteria about the suspicion of Japanese people was very, very strong. And, anyway, by the end of the day, I think all the Japanese people were calling their friends to say, “Did anyone come to your home and take your father or mother?”

AMY GOODMAN: How long was your father held for?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, he was picked up on December 7th. And, of course, he wasn’t getting any better, because they didn’t do anything for him while he was in the — first, he was in prison. And my mother kept begging, “Please let him go to a hospital, and then when he gets some treatment, then he could go back to the prison.” But we didn’t realize that when they did take him to the hospital, he was the only Japanese that was taken there, and all the other prisoners, every single one of the prisoners, were Americans, all white, no Black or Brown or anyone else. And I —

AMY GOODMAN: In the hospital.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: What?

AMY GOODMAN: In the hospital.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yes, in the only hospital in our town, San Pedro Hospital. And then they put a sheet around his bed, and it said “prisoner of war.” And we hadn’t — us kids didn’t get to go see my father yet, but my mother got permission, and she said when she saw the sheet with the “prisoner of war,” and she saw the reaction of all the American prisoners who were just brought in from Wake Island, she didn’t think he was going to last. And so, she asked the head of that hospital: Could he be given a room by himself and get some medication or something, and then, when he was feeling better, could they take him back to the prison? Because that hospital, she said, was probably worse than prison, because here were all these Americans who had been injured, you know, in Wake Island or other islands, and at least in the prison, he would be in a — probably in a cell by himself.

AMY GOODMAN: When, ultimately, did he get released? How long was he held?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: He came home. He was home not even 12 hours. He came home. It was around dinner time, 5:30. And they had a nurse come with him. And we put him in his own bedroom. And the nurse was the only one that stayed in that room. And by the next morning, she woke us up and said, “He’s gone.”

AMY GOODMAN: Were you rounded up, as well?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Not then. No. They were only rounding up first-generation Japanese.

AMY GOODMAN: So, your father died —

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Because we were American citizens.

AMY GOODMAN: Your father died after being released?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Immediately after.

YURI KOCHIYAMA: He was only home not even 12 hours, and he was gone. So, we didn’t get to talk to him. We don’t think he could have talked, the way he looked. He jumbled or mumbled. We couldn’t tell if he could see. We would put our hands in front of him. We didn’t know if he could hear. And it was so fast, he was gone.

AMY GOODMAN: We only have a minute. But were you detained, your family, after?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Everybody was. Every person of Japanese ancestry, 120,000 from those three states, for three-and-a-half states, because it was the number one war zone, so 120,000 —

AMY GOODMAN: And how long —

YURI KOCHIYAMA: What?

AMY GOODMAN: And how long were you held for?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, everybody was — at least two years, I think. And then, because there was this case, and nobody hears of, called the Endo case, where they found out in that case that actually the United States government had no right to take all the people into prison camps when there was nothing really official that could have said that we did some wrong to this country. And so —

AMY GOODMAN: My last question is: How did that shape your view of this country and what you spent the rest of your life doing?

YURI KOCHIYAMA: Well, I tell you, in this country, you don’t get much of an education. Throughout high school, through junior college, which is all I went, I didn’t know anything about the annihilation of all the Indian nations that were here. There were millions of Indians. They were wiped out practically. I don’t like to use “tribe,” that’s what the white people use on Indian, but nation after nation were wiped out. And then, when I heard about slavery, which was 10 times worse, I thought, going to another continent and kidnapping adults and children and babies, and taking the people from another continent to America, they said there’s no way they could know how many tens of thousands or a million Africans were taken. And what was the casualty? I mean, America never tells the casualty of the other side. But at least all this taught me a lesson.

AMY GOODMAN: Yuri Kochiyama. She will be 85 on May 19th. She shares the same birthday as Malcolm X. We want to say special thanks to Link TV, where we conducted this interview. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. Back in a minute.

Media Options