Guests

- Eduardo Galeanoone of the most celebrated writers from Latin America. He was born in Uruguay in 1940. He was imprisoned and forced to leave the country following the 1973 military coup. He is the author of many books including “The Open Veins of Latin America” and “Memory of Fire.”

We spend the rest of the hour with one of Latin America’s most acclaimed writers–Eduardo Galeano. His works — from the trilogy “Memory of Fire” to the classic “Open Veins of Latin America” are a unique blend of history, fiction, journalism and political analysis. His books have been translated into more than 20 languages. [includes rush transcript]

We spend the rest of the hour with one of Latin America’s most acclaimed writers–Eduardo Galeano. His works — from the trilogy “Memory of Fire” to the classic “Open Veins of Latin America” are a unique blend of history, fiction, journalism and political analysis. His books have been translated into more than 20 languages.

Born in Uruguay in 1940, Eduardo Galeano began writing newspaper articles as a teenager. Though his dream was to become a soccer player, by the age of 20 he became Editor-in-Chief of LaMarcha. A few years later, he took the top post at Montevideo’s daily newspaper Epocha. At 31, Galeano wrote his most famous book, “The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent.”

After the 1973 military coup in Uruguay, Galeano was imprisoned and forced to leave the country. He settled in Argentina where he founded and edited a cultural magazine, Crisis. After the 1976 military coup there, Galeano’s name was added to the lists of those condemned by the death squads. He moved to Spain where he began his classic work “Memory of Fire,” a three-volume narrative of the history of America, North and South. He eventually returned home to his native Uruguay where he now lives. His latest book is called “Voices of Time: A Life in Stories.” Eduado Galeano joins us today in our firehouse studio.

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: We spend the rest of the hour with one of Latin America’s most acclaimed writers: Eduardo Galeano. His works from the trilogy Memory of Fire to the classic Open Veins of Latin America are a unique blend of history, fiction, journalism and political analysis. His books have been translated into more than 20 languages. Born in Uruguay in 1940, Eduardo Galeano began writing newspaper articles as a teenager. Though his dream was to become a soccer player, by the age of 20 he became editor-in-chief of LaMarcha. A few years later, he took the top post at Montevideo’s daily newspaper Epocha. At 31, Galeano wrote his most famous book The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent.

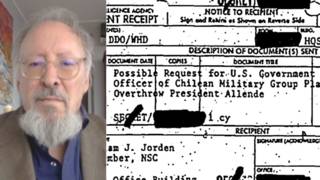

AMY GOODMAN: After the 1973 military coup in Uruguay, Galeano was imprisoned and forced to leave the country. He settled in Argentina, where he founded and edited a cultural magazine called Crisis. After the '76 military coup there, Galeano's name was added to the list of those condemned by the death squad. He moved to Spain, where he began his classic work Memory of Fire, a three-volume narrative of the history of America, North and South. He eventually returned home to his native Uruguay, where he now lives. His latest book is called Voices of Time: A Life in Stories.

Eduardo Galeano joins us for the rest of the hour in our Firehouse studio. Welcome to Democracy Now!

EDUARDO GALEANO: Hello. Hello, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s very good to have you with us. Let’s start where we left off in headlines, and that’s the issue of immigration. How do you see, as you look from the south to the United States in the north, the issue of the wall, the issue of the treatment of immigrants in this country?

EDUARDO GALEANO: It’s a sad story. A daily sad story. I wonder if our time will be remembered as a period, a terrible period in human history, in which money was free to go and come and come back and go again. But people, not.

AMY GOODMAN: You wrote about immigration in your new book Voices of Time.

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes. There are some stories about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Could you read an excerpt?

EDUARDO GALEANO: One of them, which is quite short. It’s a document on history. Scientific. Pure science. Objective. There is a religion of objectivity here, so I respect it. And this is — you’ll see, you’ll see. “Christopher Columbus couldn’t discover America, because he didn’t have a visa or even a passport.

“Pedro Alvares Cabral couldn’t get off the boat in Brazil, because he might have been carrying smallpox, measles, the flu or other foreign plagues.

“Hernan Cortes and Francisco Pizarro never even began the conquest of Mexico and Peru, because they didn’t have working papers.

“Pedro de Alvarado was turned away from Guatemala, and Pedro de Valdivia couldn’t even enter Chile, because they didn’t bring proof of a clean record.

“And the Mayflower pilgrims were sent back to sea from the coast of Massachusetts: the immigration quotas were full.”

AMY GOODMAN: Eduardo Galeano, reading from his new book Voices of Time: A Life in Stories. We’ll be back with him in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Our guest, Eduardo Galeano, one of the most celebrated writers on this continent, born in Uruguay in 1940, imprisoned, forced to leave the country following the coup there, author of many books. His classic, The Open Veins of Latin America, his most recent, Voices of Time: A Life in Stories. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’d like to ask you, you’ve, obviously, over the decades now you spanned enormous changes that have been occurring in Latin America. You were yourself imprisoned during the military dictatorship in Uruguay. You know directly of the problems of Operation Condor and the other terror that spread across the continent in those years. And now there’s enormous changes occurring in many of these countries, if not economically, certainly politically at this point. Your sense of how Latin America is changing or has changed in recent decades?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes, I think that all these recent events, elections won by progressive forces and a lot of different movings, is like something that’s moving on and expressing a need, a will of change, but we are carrying a very heavy burden on our backs, which is what I call “the traditional culture of impotence,” which is something condemning you, dooming you to be eternally crippled, because there is a cultural saying and repeating, “You can’t.” You can’t walk with your own legs. You are not able to think with your own head. You cannot feel with your own heart, and so you’re obliged to buy legs, heart, mind, outside as import products. This is our worst enemy, I think.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Much of your writing is about memory. You say the great problem of amnesia in Latin America. Could you talk about that a little bit?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yeah. It’s forbidden to remember. I’m not in love with the past, you know. For instance, I’m a very bad visitor in museums, because I get bored soon, and I always prefer a live life and in present days. But there is no frontier between past and present when you can revisit the past and make it alive again. And then it would be a good mirror to look at yourself and to understand. Perhaps it would help to understand your present actuality, your present reality. If you don’t know where do you come from, it would be very difficult to understand where are you going.

AMY GOODMAN: Eduardo Galeano, you addressed the World Social Forum in Brazil, and on February 15, 2003, on the eve of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, they asked you to make a statement for all, that you entitled “To Say No.” What was your point?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes, it’s true. I don’t remember exactly, but I suppose I said that this was a criminal war looking for oil, that if — I don’t remember exactly, but it would be something like saying, well, if Iraq produces tomatoes or carrots, nobody would invade it. The country was invaded for other reasons, unconfessed reasons. The alibi was at that time that Iraq was a danger for humanity, the massive destruction weapons, the supposed complicity or participation of Saddam Hussein in the September 11 attack.

My mother used to say — to tell me when I was a child, a little child, “Lies have short legs.” Poor mom. She was wrong. Lies have very, very long legs, and they run fast, very fast, faster than liars. Because afterwards, in the United States, in Great Britain, everywhere, there was an official recognition that it was not true, that it was an invention, that weapons of mass destruction didn’t exist and that Saddam Hussein had nothing to do with the Twin Towers tragedy. But anyway, there are lots of people still believing that it was true, and finding that this may be a good explanation of this absurd war. More or less it was something like this.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it’s fair to say Iraq saved Latin America, that with the attention of President Bush on Iraq, we’re seeing Latin America go in a very different direction?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Nobody says, hmm? I think it’s true when President Bush tells us each day that we are suffering the high risks of being attacked by terrorism. It’s true. And terrorism made the Iraq war, and they perhaps may — today or tomorrow, I don’t know — invade some Latin American country. It’s a tradition of the terrorist, imperialist power in the world. Who knows? We are not safe. You are not safe. Nobody is safe from a possible attack from this machine of war, this big structure we have built — they have built, in a global dimension. This $2,600 million spent each day to kill other people, this machine of killing peoples, devouring the world resources, eating the world resources each day. So this is a terrorist structure indeed, and we are in danger, so President Bush is right, I think. We are suffering a terrorist menace.

JUAN GONZALEZ: One of the enormous changes, it seems to me, in Latin America, has been, especially in the last decade or two, sort of the rise of indigenous demands for rights, whether it’s in Chiapas in Mexico or Evo Morales and what’s going on in Ecuador. Your sense of this long — because you have written about it. You wrote about it in Open Veins of Latin America, how the native peoples of Latin America, for so long oppressed and kept down by the mulatto or the White elites of those countries, and how this change is having an impact on the continent.

EDUARDO GALEANO: One of the oldest traditions in America, all America, because we are America also. The name “America” has been kidnapped by the United States. Really, we are part of America, no? And so in the three — in all Americas, from North to South, from Alaska to Chile, one of the most beautiful traditions is the identity between word and fact in the Indian tradition. I mean the sacred nature of, the sacred character of word, of language. And this is something not so frequent in the dominant cultures, but they have kept it alive, this faith on words, on the sacred power of words.

Bolivia has now an Indian president, Evo Morales. It was at first a scandal. Evo Morales, an Indian president, and an Indian who was not ashamed of being what he is. First a scandal. The scandal would have been the fact that Bolivia took two centuries to realize that it was a country with Indian majority in the population, and it would be perfectly normal that they have an Indian president as Evo Morales. But this was the first scandal.

Now we have the second, and the second scandal came from the deep respect Evo Morales has for this Indian tradition of devotion to words. Why are so many people angry against him? Because he nationalized oil and gas. That’s it. He did what he promised he would do, which is a cardinal sin from the viewpoint of a system based on lies, that teaches you to lie each day and each night, even when you’re having dreams or nightmares.

AMY GOODMAN: And your assessment, Eduardo Galeano, of the Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and this titanic struggle he is in with the President of the United States, President Bush?

EDUARDO GALEANO: What I do think about it? No, I think that Chavez is being demonized. I mean, he’s one of the demons. I don’t know if he will be demon tomorrow or not, but he’s nowadays a good demon, useful for an international war machine who is always hungry of demons. I mean, they need demons to justify the fact that the world is just spending fortunes in the military industry. So, weapons need wars, and wars need alibis, and alibis are demons, the evil forces which are our daily danger. And so they have invented that Chavez may be a danger for humanity and that he’s a tyrant and he’s a despotic dictator. He won eight elections. It’s strange, being a dictator, eight clean elections won by him.

I was an international observer in this plebiscite he did — I don’t remember now, but something like a couple of years ago — which was quite exceptional in human history. The first time, perhaps, in which a president would say to the people, “Here is my post, my job. If you decide that I’m not a good president, then I’ll go out,” and people voted to keep him in power. Jimmy Carter was also an international observer. We worked together — and Gaviria, and it was unanimous, the certitude that this was a clean election. Then I have never seen the case of a tyrant being so democratically confirmed so many times. It’s strange.

Where does this hate come from? Perhaps — perhaps, I don’t know, because he’s a real patriot. I mean, he’s taking care of his people in his country. And patriotism nowadays is a privilege of rich countries. If you are the leader of a third world country, then your patriotism would be always suspicious of being populism or terrorism or something — some other —ism -— I don’t know — terribleism, they may invent to falsify the love you feel for your own people.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’d like to turn for a moment to your writing style. You defy classification in terms of the kinds of books that you produce. It’s part poetry, part political analysis.

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes

JUAN GONZALEZ: You don’t follow a long narrative discourse, but you thread together pieces of a tapestry. How did you develop that style? Why did you decide to write in that style?

EDUARDO GALEANO: I never decided. It’s something — I’m written by my books. I mean, they write me, so I never decide anything. Well, I was always looking for a language who could integrate everything that has been culturally divorced from, for instance, heart and mind. So I was looking for a feel-thinking language, sentipensante, “feel-thinking.” It’s a word. I didn’t invent the word. It’s a word I heard years ago in the Colombian coast. A fisherman told me, ”Hay gigrere en las palabras sentipensantes,” when I told him I was a writer. “Ah, you’re a writer.” “Yes.” “Oh.” And he asked me if I was using a sentipensante language, a feel-thinking language. And so, he was a master. I mean, I learned a lot from this sentence forever. I am a sentipensante.

I think one of the divorces that has avoided a full integration of human condition is this divorce between our emotions and our ideas. In other divorces, separating journalists, for instance, literary journalists, saying, well, this is an essay. This is a poem. This is a novel. This is an — I don’t know what. And I don’t believe in frontiers. I think that in no —- I don’t believe at all in frontiers. And then, how would I practice the alguanas, I would say, the immigration controls between literary journalists? I believe that -—

AMY GOODMAN: You don’t believe in borders.

EDUARDO GALEANO: No. I think that when the world — perhaps one day the world, the world, our world, won’t be upside down, and then any newborn human being will be welcome. Saying, “Welcome. Come. Come in. Enter. The entire earth will be your kingdom. Your legs will be your passport, valid forever.” And for me, this is true also for words. I mean, the same thing with words, persons, words. I really believe in the universal dimension of human condition, not globalization, which is the universal dimension of money, but the universal dimension of our human passions.

AMY GOODMAN: Eduardo Galeano, we have to break for a moment, but we will be back. Eduardo Galeano is author of, among other books, his latest, Voices of Time: A Life in Stories.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Our guest for the hour is Eduardo Galeano, one of the most celebrated writers in Latin America, born in Uruguay, lives there now, had to leave after the coup, was imprisoned for a time there, has written many books, among them his classic The Open Veins of Latin America, his trilogy Memory of Fire, his most recent book Voices of Time: A Life in Stories. You’ve also written Soccer in Sun and Shadow. The World Cup is coming up in Germany in a few weeks.

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re a great writer, but it wasn’t your highest aspiration. It was to be a soccer player. Talk about the significance of soccer.

EDUARDO GALEANO: All Uruguayans. We all want to become soccer players, and I could not, because I was terribly bad in the fields. In Uruguay, in the — como se llama, maternidades? — maternities, they’re so noisy, because all babies are born crying, “Gooooool! Goooool! Goooool!” It’s terrible to — you can’t stand it. They should be more silent, more quiet.

And that said, it’s our national destiny. Uruguay was world champion twice, before the first World Cup in two Olympic games: '24, ’28. Later the first world championship was in Montevideo in Uruguay. And later, we were again world champions in 1950, against all evidence, because Uruguay is such a small country. We are three million. Nothing. Less people than any neighborhood in Buenos Aires or Sao Paulo. And anyway, we were able to do so, and then it's a national identity.

All Uruguayans are experts in soccer. That’s why when I wrote the book, trying to do with the hands what I was not able to do with my legs, I was scrambling in panic, because all Uruguayans know everything about soccer. They are soccer experts. And nowadays our real soccer —- I mean, our players playing are not exactly the best in the world. We are outside the next -—

AMY GOODMAN: How does soccer and politics intertwine?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Everywhere, every day, soccer is a source of power nowadays. Silvio Berlusconi is the result of the success of the Milan club in Italy. And almost all politicians in the Latin countries have close relationships to not only president or politicians, but even military dictators. One of the first acts of General Pinochet in Chile was to become president of a very popular soccer team, Colo-Colo, because he knew perfectly well that soccer is a source of prestige and power.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Sort of like a George Bush with the Texas Rangers, right?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yeah. It would be the equivalent, yes. But, I mean that, you know, it’s high business. Nowadays it’s not only a source of prestige, but also big business in futbol — soccer, as you call it here in the States. But I don’t know why the miracle exists, and soccer is always able to give you a feast, a feast to the eyes watching it when it’s very, very well played and a feast to the legs when you’re playing it. And there are, there still are. I don’t know how, but there they are. Ronaldinho, for instance. Players able to play for the joy, the pleasure of playing, instead of playing just because they are obliged to do it, professionally obliged to do it. It’s like an election. We are all making each day, being as we are, obliged to live life as a duty, but secretly willing to live it as a feast.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’d like to ask you, you started as a journalist, and obviously journalism in Latin America has a long tradition of being an incubator for political leaders in Latin America. But your sense of how journalism has changed in recent years there? I mean, here in the United States, there’s a huge battle over the increasing concentration of ownership.

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And I know in Latin America there are the huge chains of Venevision and Globalvision. How has journalism changed in Latin America in recent years?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yeah, there is a concentration of power nowadays on a world scale, in Latin America and everywhere, even here in the States. And this is not good. Not good news for humanity, this concentration of power, because it threatens to reduce the freedom of expression to the freedom of oppression. I mean, it becomes the monopoly privilege of a small group of enterprises, who are closing the big factories of public opinion in a worldwide scale.

But democracy now exists, and a lot of other independent spaces open everywhere. They have a narrow space nowadays. If you compare, for instance, a proportion of independent media in the '40s or the ’50s, half a century ago, with the actual proportion, the present proportion, it's terrifying. I mean, it’s terrible, the concentration of everything. But there are new ways, internet and so on, that are giving expression to the voiceless movements or the movements condemned to be sounding in campana de palo — how is it? — in wooden bells.

AMY GOODMAN: Wooden bells, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: In wooden bells. And these new ways are exploding in the contemporary world and opening, broadening the spaces for independent expressions. I now repentido, because I didn’t believe in it at the beginning. I mean, I mistrusted it, all this internet and so on, the cybernetic new ways of — no, I was against it, because I always had a strong suspicion that machines drink at night. When nobody sees them, they drink. And then, the day after, they do all sort of disasters — but nowadays I accept that it’s something really new and a source of hope — because internet was born for military purposes, articulated by the Pentagon to program on a world scale their operations. And nowadays, it’s serving also for military purposes and business and so on, but it’s opening the spaces to breathe, respirar, that we need so much.

AMY GOODMAN: Eduardo Galeano, I wanted to ask another question about journalism, which has to do with what is happening to journalists in Iraq. The number of journalists who have been killed, it looks like well over a hundred now, Western journalists, photographers, videographers and writers, and particularly Iraqi and Arab journalists.

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yeah, particularly. Most of them, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Your thoughts about the power of journalism and the power of pictures, especially in a time of war?

EDUARDO GALEANO: In the categories of death, because, indeed, a foreign journalist is much more important than an Iraqi journalist dead, and this is because the world, the entire world, is still sick from racism. And so, we have citizens of first class, second class, third class, fourth class, and corpses of first class, second, third, fourth. If you can design a proportion of killed people, civilian people killed in the Iraqi war, most of them women and children, in proportion to the U.S. population, it’s a terrifying sifra, numero.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Figure.

EDUARDO GALEANO: Figure. Half a million. It would make more or less half a million. Can you imagine the scandal? It would take millenniums to forget it. Half a million U.S. people — Americans, as it’s said — most of them women and children, killed by a foreign attack? Iraq invading the United States and killing half a million people here? Millenniums, it would take to forget it. But as they are Iraqis, we read each day in the newspapers, repeating, 30 people killed, 50 people killed, 100 people killed. It turns to be a habit, something normal, as part of nature. And the same thing for journalists. It’s sad to say it, but one Iraqi life is not the same than one British or U.S. or French or any other lives taken in the noble job of telling what’s happening [inaudible].

AMY GOODMAN: How do you engage in your craft of writing in a time that is so difficult, so desperate right now? How do you clear your head? What is your ritual? Isabel Allende, who wrote the introduction to the latest edition of Open Veins of Latin America, she has talked about — she begins on one date in a year, in January, if she ever begins a book. How do you do it?

EDUARDO GALEANO: No, I have no discipline at all. I learned to write really from music, a Cuban musician. He played drum, tambor_, in Santiago a lot of years ago. He was absolutely magic. This drum was wonderful, playing music on earth but directly from heaven. It was so marvelous that I asked him, “Please give me your secret.” And he said, “_Yo toco cuando me pica la mano.” Now you should shout at me, because I cannot say it in English.

JUAN GONZALEZ: I play when my hand begins to itch.

EDUARDO GALEANO: That’s it. And I write when my hand begin to itch. I mean, I never give myself orders, saying “Now, you must write,” or “You must write about this subject,” or “You must say this or that,” or — no. I leave it. Let it be. I leave it as something growing inside. And it’s hard work. Each one of these short stories, a lot to write, have, some of them 20, 30, 40 versions before being published. It’s very hard for me.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you read one last one for us?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes. “In the summer of 1972, Carlos Lenkersdorf heard this word for the first time.

“He had been invited to an assembly of Tzetzal Indians in the town of Bachajon, and he did not understand a thing. He was unfamiliar with the language, and to him the heated discussion sounded like some sort of crazy rain.

“The word tik came through the downpour. Everyone said it, repeated it — tik, tik tik — and its pitter-patter rose above the torrent of voices. It was an assembly in the key of tik.

“Carlos had been around a lot, and he knew that in all languages I is the word used most often. I. But tik, the word that shines at the heart of the sayings and doings of these Mayan communities, means 'we.'”

JUAN GONZALEZ: I’d like to ask you, in terms of your — you have a chance now, and you’re going to be going around the United States to get a message to the American people. This is the most powerful nation in the world. We’re probably the largest empire the world has ever seen. What is the role of the American people in the world today, and what should be their role, as distinct from the government’s?

EDUARDO GALEANO: Yes. I hope they may hear other voices. And it would help to understand that the world is much more than the U.S. I mean, this is a very important country, indeed. And I come from a small country. Most people doesn’t even know where it is. But we are all important. We are all able to say something that deserves to be heard. And when I was living here in a period I had been during three, four months, teaching at some university, so on, I was surprised by the fact that the world didn’t exist for the media, for the big media. It didn’t exist. Almost no news about the world. And when the news came, most of the people didn’t know what’s it about. One of my masters, Ambrose Pierce, one century ago said, “Wars are not so bad. At least for the U.S. For us, wars are not so bad. Wars teach us geography.”

AMY GOODMAN: Eduardo Galeano, I want to thank you very much for being with us, one of the great writers in the world today, his latest book Voices of Time: A Life in Stories.

Media Options