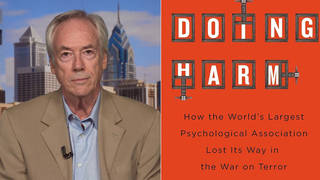

We speak with leading American psychiatrist Dr. Robert Jay Lifton about the psychological dimensions of war and occupation and the role of doctors in interrogation and torture. Lifton is co-editor of a new book titled “Crimes of War: Iraq.” [includes rush transcript]

We spend the rest of the hour looking at the psychological dimensions of war and occupation and the role of doctors in interrogation and torture with leading American psychiatrist and professor, Dr. Robert Jay Lifton.

A lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Lifton is author of many books including, “Superpower Syndrome” and “The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide.” He is one of the editors of a new book titled “Crimes of War: Iraq.” The book is being published 35 years after Lifton and the same editorial team published the landmark book “Crimes of War” about Vietnam.

- Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, author of many books including “Crimes of War: Iraq,” “Superpower Syndrome” and “The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Robert Jay Lifton joined us in our Firehouse studio on Friday, and I asked him to talk about the similarities between Vietnam and Iraq.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: I find it very sad because Richard Faulk and I, together then with Gabriel Coco, wrote a book that really derived from the Nuremberg obligation to oppose the war crimes of one’s own government. We did that thirty-five years ago in relation to Vietnam, and now we find ourselves doing the same thing. This book is modeled after the first book in relation to Iraq, and that’s a very unhappy sequence, but we felt it should be done.

AMY GOODMAN: You write a few articles that come out of your pieces in, among other places, the New England Journal of Medicine about the role of doctors, the role of psychologists, psychiatrists when it comes to torture. Can you expound on that?

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Yes, you know, since my work on Nazi doctors, I’ve been very concerned with medical behavior and misbehavior, and it isn’t that anything that American doctors did was like the Nazis, not at all, but from the extremity of Nazi behavior you can understand a lot about less extreme but still disturbing violations of medical ethics and of, really, human behavior.

What I wrote about was at least three aspects of medical behavior in Guantanamo, in Afghanistan and in Abu Ghraib in particular, which included first, the failure to report injuries that could only have been caused by torture or help in the delay or falsication of death certificates, and then collaboration with interrogators by providing them medical records that could help focus on the weaknesses of detainees. All this and now further, collaboration with interroragors, which has been a big issue now for the American Psychiatric and American Psychological Association. So I wrote about all those things in terms of violation of medical ethics and psychological ethics, and I feel quite strongly about it.

AMY GOODMAN: What evidence do you have, for example, in each of the three examples you give, on the issue of changing date of — time of death?

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Oh, there’s all kinds of evidence by the human rights groups, they’ve dug up the death certificates which were simply false. They were described as people dying from natural causes or some sort of illness, when they died from the abuse during captivity, and this has been documented by human rights groups as has the collaboration with interrogators and the injuries that they failed to report that had to be caused by abuse. All this is well documented by the human rights groups, and now, even the military doesn’t deny it. At first they did. Now the military is saying, ’We’re trying to improve it, and we’re asking psychologists to collaborate in interrogation and not so much psychiatrists.’ That doesn’t seem like a big improvement to me.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, you had a debate on Democracy Now! with, among others, Dr. Stephen Behnke, Director of Ethics at the APA, the American Psychological Association. I wanted to play a clip for a moment of what he said.

DR. STEPHEN BEHNKE: I have a letter from Physicians for Human Rights that was sent to the American Psychological Association, and in that letter that was written by the executive director of Physicians for Human Rights, he allows for the possibilities that, in fact, there may be a role for psychologists in interrogation processes that is — and this is his phrase, “quite benign.” So for us, the question is not whether psychologists may be involved in these processes, it’s how psychologists may be involved in these activities in an ethical manner.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Dr. Stephen Behnke. Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, your response?

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, the problem is having psychologists related to interrogations at all. Interrogations are a destructive process. They’re saying — some of the American Psychological Association people. They’re split on this — and the military, that the psychologists can be divided. There can be those clinical psychologists who are engaged in therapy and helping people in healing, and there can be those consultants who consult in interrogation, and consulting in interrogation, they say, is to humanize interrogation, but in effect, it’s helping interrogators to break down the detainees or the prisoners.

That’s not a role for psychologists. With psychiatrists, it’s clearer by tradition because psychiatrists are physicians, and we take an oath that we do no harm, and for that reason, psychiatrists could mobilize a lot of sentiment about that and the American Psychiatric Association has taken a very good position forbidding psychiatrists to be involved in any interrogations. With psychologists, the situation is less clear because there isn’t any parallel oath, but there should be a parallel ethics which say that psychologists are meant to heal and not to break down, and therefore any consulting or involvement in interrogations with interrogators on the part of psychologists should be prohibited by the American Psychological association.

AMY GOODMAN: In your piece, “Doctors and Torture,” that you wrote for the New England Journal of Medicine, you talk about psychologists handing over notes, in very significant part, to an interrogator.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Absolutely. They have behavorial science teams, so-called “Biscuit” teams, which have worked with interrogators, have handed over medical records, and have worked with them to look for weak spots, points of vulnerability that can be used in breaking down prisoners. That’s a very dubious role for people who are in the health care business in the military, and the military suffers from it.

What happens is that you get a conflict between the healing commitment of medical personnel on the one hand and sometime pressures from command, which are to do other things than healing and where intense interrogation that leads to abuse becomes the norm, as it has in certain places like Abu Ghraib, then psychologists and psychiatrists are drawn into what I call an 'atrocity-producing situation,' a situation so structured, military and psychologically, that ordinary people are capable, when entering it, of committing atrocities.

AMY GOODMAN: Go further into that.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, for instance, when I did my work in Vietnam with Vietnam veterans, I found that the military policies of free fire zones and body counts, along with the angry grief of soldiers when buddies were killed and they couldn’t find the enemy — the enemy was everywhere and nowhere — created an atrocity-producing situation in which ordinary young people, who weren’t bad in any basic way, could be psychologically drawn into atrocities.

I found now, in studying the Iraq situation, that there’s a parallel situation. It’s another counter-insurgency war with a non-white population in a place where we’re resented, and with an enemy that is very elusive and difficult to identify, and that creates both a military and psychological situation in which ordinary young men and women, no better or worse than you or me, are capable of committing atrocities.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, you wrote a piece in Editor and Publisher called “Haditha: In an Atrocity-Producing Situation, Who is to Blame?”

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: That’s right. Well, I compared Haditha to My Lai because there is a similar sequence. It’s striking. With My Lai, there were losses and pain and land mines and booby traps, losing men in a very dangerous situation, the angry grief that resulted and the policies of slaughter that were militarily permitted. And there was the death of a much loved sergeant, a man named Sergeant Cox, just before My Lai, just before the slaughter. And then the night before My Lai, there was a combination funeral ceremony and military pep talk in which the message was to go out and get them. Go out and get everyone.

There is a very parallel sequence at Haditha, in which there were something like twenty marines killed three months earlier in a different unit. Then this unit came in, they had a death, their first death three days before the incident and then on the day of the incident, another death of a much-loved man who was a sniper, who saved lives, and they went berserk, and they killed civilians rather randomly — a much more smaller scale, twenty-four as opposed to close to five hundred at My Lai, but a parallel series of psychological pressures. And again, it’s a combination of military policy in a counterinsurgency war with an elusive enemy on the one hand, and the angry grief of soldiers who lose buddies and have a desperate need to get back at the enemy, to the extent of making women and children into the enemy.

AMY GOODMAN: Haditha, also Hamandiya, which was an example of one Iraqi man being killed. Now it’s being reported, for example, by Newsweek, that the unit there, the year before was in Fallujah, and this astounding paragraph from Newsweek that I wanted to read to you: “The marines know how to get psyched up for a big fight. In November of 2004, before the battle of Fallujah, the Third Battalion, First Marines, better known as the 3-1 or Thundering Third, held a chariot race. Horses had been confiscated from suspected insurgents, and charioteers were urged to go all out.

The men of Kilo Company, honored to be first into the city on the day of the battle, wore togas and cardboard helmets and hoisted a shield emblazoned with a large K. As speakers blasted a heavy metal song “Cum On Feel the Noize,” the warriors of Kilo Company carried a homemade mace and a ball and chain studded with M-16 bullets. A company captain intoned a line from a scene in the movie Gladiator, in which the Romans prepare to slaughter the barbarians. “What you do here echoes in eternity.” That’s the lead paragraph from an article in Newsweek magazine. The article goes on to say that Kilo Company, from Fallujah, arrived in Haditha in the fall of 2005. Your response to that.

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, it’s, you know, it’s almost a caricature of invoking the warrior ethos. The warrior ethos is: you kill in noble ways for the glory of your country and yourselves, and that’s what’s put forward, in a way almost desperately in that description, because it’s so much questioned in Iraq. You know, there have been surveys and studies that bring out the doubts that the soldiers fighting in Iraq have about the very war they’re fighting. And this idea of rendering them Roman gladiators is a way of trying to mobilize and reconstitute some warrior energies.

It’s very sad to hear that description of men and women fighting in one’s name, and of course it could contribute to what we saw happen at Haditha. The other thing I’d want to say is that the significance of something like Haditha is not just that event. You have to suspect that events like that are occurring all over Iraq, because there are similar conditions, and similar strains, and similar losses on the one hand, and similar frustrations about finding the enemy in terms of military vulnerability, on the other. So, as in the case of My Lai, Haditha is unlikely to be simply a single event but rather to represent something going on much more broadly.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, post-traumatic stress disorder. Can you talk about that?

DR. ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, post-traumatic stress has come up very actively recently. We — I, with a committee of people, helped institute the concept, to put it in the diagnostic and statistical manual of the American Psychiatric Association, and the diagnosis has the virtue of creating a category that can encompass suffering in war. And of course, there have been confusions and abuses, as there are about any kind of diagnosis, but now there’s a systematic attack, you might say, on the whole concept, coming from the right, because they want to deny or minimize the pain that war causes and the symptoms that the result from the war in Iraq in particular.

If you can deny or minimize the occurrence of post-traumatic effects then you can be saying, 'Maybe war isn't so bad for you. Maybe it’s even good for you, and this war in Iraq isn’t really harming people so much.’ But that’s belied by reports that come from no one else but the military itself. There are honorable psychiatrists and doctors and psychologists in the military who have done studies and show the widespread occurrence of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

They’re very widespread. They’d have to be under those extreme conditions, and there have been reports now that it’s even more widespread than the military has recognized, and some of it is insufficiently treated, and then you have some bad effects, sometimes violence, sometimes suicide and other forms of suffering of veterans who come back from Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: Psychiatrist and author, Robert Jay Lifton. We’ll be back with him in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Welcome back to Democracy Now! As we return to our interview with the renowned American psychiatrist Dr. Robert Jay Lifton.

AMY GOODMAN: I just bumped into a soldier who just returned from Kabul, from Afghanistan, and they go to decompress at Fort Polk. And I asked, “how do they decompress?” And he said, twitching very nervously as he spoke, “we clean our weapons for two hours a day and then we’re brought into a room and asked if we want any psychological help.” “is it in a room in front of everyone else?” And he said, “yeah, you can raise your hand.” I said “How many people raised their hand?” He said “two people raised their hand.”

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Some of the military studies again, coming from within the military, say that there’s a kind of hesitation to seek psychological help because it’s considered in some way tainted, or a sign of weakness, and it could adversely affect your military career. There’s always the sequence of discharge and sometimes some sort of questionnaires given out, or the kind of question you mentioned is asked, “do you need psychological help?”

AMY GOODMAN: In a large room of people?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Sometimes in a large room, or sometimes even a form to fill out, but there’s a reluctance to say that one has symptoms or needs help, because one feels it may delay the discharge process or in some way it may designate one as an inferior person or affect one’s treatment by the military if one is staying in the military. So there are much more — there’s much more post-traumatic stress disorder in relation to fighting in Iraq than we had reported and we have reported a great deal of it.

AMY GOODMAN: And the effect of going back time after time, a first tour of duty, then a second, then a third, even a fourth?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Yeah. There can be a terrible mixture of people who suffer from post-traumatic effects and from repeated tours in Iraq. Sometimes bitterly, against their will. Sometimes, though, they may volunteer for it and seek more tours, because their way of dealing with their pain is to embrace their buddies and seek to go on fighting, and might feel guilty in some cases if they were to leave their buddies. That’s a well-known psychological pattern with people in combat. But by and large, the repeated tours have undoubtedly contributed enormously to post-traumatic symptoms. And the whole structure in Iraq is made to order for post-traumatic stress disorder, in some degree, and we’re seeing it.

AMY GOODMAN: How? The structure.

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: It has to do with a continuing insurgency or resistance in which one has — the American military has all kinds of technological superiority, but can’t overcome the resistance and becomes vulnerable. Because in that situation you can’t identify the enemy. And you see buddies die. You feel vulnerable yourself. You don’t have any clear outlet for your energies and your hostility because it’s so difficult to find the enemy, and there’s likely to be an overreaction, as we’ve seen, when you find someone who you identify, often mistakenly, as the enemy. You can have post-traumatic symptoms that involve not only your own vulnerability and the death of buddies next to one — there’s no greater stress in wartime — but also the stress caused by the death of Iraqi civilians.

When you talk to, or hear talk, some of the Iraq veterans, Americans coming back from Iraq, especially who have begun to speak out against the war, they talk about large-scale killing of civilians as a form of pain, which they experience, either witnessing it or the fear that perhaps they killed civilians. So we talk about not having any feeling for Iraq’s civilians, but I think this killing of Iraqi civilians has its psychological effects on Americans and that contributes to post-traumatic stress.

AMY GOODMAN: You have the wives of one of the Marines at Haditha saying we’re talking about a totally strung out unit. This was in Newsweek. I mean, on drugs, on alcohol.

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, they’re strung out because they’re under that extreme duress. It’s as if they’re trapped. There’s no exit. That’s why, in writing about Vietnam veterans — and now I would say the same about Americans fighting in Iraq — they become both victims and executioners. This is what — these are the two roles that Albert Camus warned us never to assume, always to resist. So they’re perpetrators, but they’re also victims. And there’s something deeply troubling about placing young American men and women in a situation where they’re psychologically likely to commit atrocities and be perpetrators, and also, at the same time, be victims of that same situation, in terms of the trauma, or even death, that it may cause them.

AMY GOODMAN: And then a media, in this country, that will not allow one to be talked about by talking about the other. When you talk about them being perpetrators, they say, “How dare you? They’re victims.”

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: That’s right. The truth is to say both, and one can bring great sympathy to Americans put into that situation. On the other hand, one has to — anybody has to assume responsibility for what he or she does in that situation. And that’s the complicated balance that we need ethically. When I worked with anti-war veterans, it was interesting that in the [unintelligible], they insisted upon taking some responsibility for what happened. But they also said, “it’s not just our responsibility, it’s the whole damn society for sending us there.”

AMY GOODMAN: Before we get to the whole society, what about the chain of command, and how does that fit in?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: When you talk about atrocity-producing situations, it’s always the foot soldiers who get prosecuted and who are blamed, but the ultimate responsibility has to do with those environments and those who create those environments. And those who create those environments are the military and civilian leaders going right up to the White House. So the responsibility lies at the top of the Department of Defense, and in the White House, and it has to do with how they define, or don’t define, torture with policies they establish in relation to counterinsurgency war in Iraq. And with the deceptions they’ve brought forward about the whole situation. So yes, the responsibility is thrust upon the foot soldiers alone all too often. But greater responsibility certainly lies with the higher ups going right up to the top of the Department of Defense and the White House.

AMY GOODMAN: Criminal responsibility?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: I think it is criminal responsibility. We call our book Crimes of War: Iraq — we’re talking about the American crimes of war, and the responsibility for those crimes of war comes from the top.

AMY GOODMAN: Do we have figures? Does the military have figures on soldier suicides?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: They do have figures and the soldier suicide — it’s still early, but the soldier suicide seems to be higher than ordinarily occurs. And it has to do with those conditions of feeling trapped.

AMY GOODMAN: Then also the question of how they’re counted — if you commit suicide in Iraq, is that considered a casualty? If you come home and, months later, commit suicide, is that considered a casualty of war?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, very often — yes, if you’re writing about war casualties, you may well leave out the veterans and those who are discharged and commit suicide later on. But, as their families know all too painfully, they are casualties of war when you take your life and civilian life after having fought in a war.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Lifton, what about detainee suicide attempts like those at Guantanamo? The people who are going on hunger fasts? The people who are attempting suicide?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, nobody knows, other than the immediate military, just what goes on at Guantanamo. It’s been kept covered, really, and yet enough has been revealed about it by groups like the Red Cross and others, who have gotten just a peek of what happened there, to make everybody deeply troubled about it. And it is interesting that the call to close Guantanamo has come from so many different sources. It’s as if the world has come to recognize that we’ve created, in Guantanamo, a whole institution unworthy of anything in our better ideals, and it includes torture and abuse of various kinds. Moreover, it doesn’t seem to create any clear-cut criminals. We haven’t found very many people who have committed crimes that we can identify who are imprisoned in Guantanamo. There haven’t been cases against those prisoners. They’ve mostly been held without any clear charge. So that the whole experience of Guantanamo is a fiasco psychologically, ethically and militarily.

AMY GOODMAN: The issue of what constitutes torture — Professor Al McCoy wrote a very interesting piece about the question of torture, looking at the history of CIA investigation, into torture techniques and ultimately finding that no matter how we could talk about the brutality of physical torture techniques, that the most effective ways to break down an individual are the basic psychological isolation, self-infliction of pain, meaning forcing them to stress positions, where they have to stand or sit, and I think of Rumsfeld saying this or writing in a memo on the side, “I stand for hours a day.”

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well that’s been one of the outrages, the narrow definition of torture by the administration, and it’s been put forward by its legal team so that torture becomes described as only something that causes organ injury. Something that’s life-threatening. But fortunately, the Physicians for Human Rights has put out an excellent, detailed report on psychological torture, which of course includes intense sleep deprivation, and isolation, and threats of various kinds, manipulations, humiliation. There is a whole array of methods of psychological torture, and that is torture by anyone’s definition, except maybe Gonzalez in the Justice Department, and that’s again a scandal in terms of American legal tradition, which has its reverberations right in the field and whoever Americans are interrogating, prisoners, and it affects doctors as well.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Robert Jay Lifton. His book is Crimes of War: Iraq. He already wrote one on Vietnam by that title, Crimes of War. In the book, you refer to Nazi doctors, and you wrote a seminal book called Nazi Doctors. There’s a lot of talk, how dare anyone make any reference to World War II, to the Holocaust, to Nazis.

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: In my piece about doctors in Iraq, of course I invoke Nazi doctors, but I did it very carefully. That is, whenever I bring up Nazi doctors, of course I do it carefully. The Nazi doctors and Nazis in general had many unique characteristics. They try to round up all the Jews in Europe and simply murder them. That was fairly unique. And Nazi doctors got involved directly in the killing process. Doctors have done that but rarely. And American doctors haven’t done anything like this. But you see, in that extreme behavior of Nazi doctors, indications of how doctors can be drawn into destructive behavior, and even murderous behavior, and they can be drawn into it by being socialized to certain environments, so that Nazi doctors were socialized into being doctors, into medicine, and then socialized into military medicine, and then socialized into military medicine in the death camps, which came to include killing. Whatever the norm was, they were socialized to it and they joined it.

In a different way, never this extreme but in a way that is illuminated by Nazi doctors, American doctors at Abu Ghraib were socialized into that environment. You have to get along with the people you’re working with and you internalize some of the norms that take shape in that environment as in Abu Ghraib. When torture periodically became a norm at Abu Ghraib, in some degree doctors had to be socialized into it. And I know from having been a military doctor for a couple of years way back at the end of Korean war, you’re torn as a physician between on the one hand, your healing commitment and on the other hand, your involvement with command and with the immediate military environment, which makes psychological demands on you and those two can come into conflict as certainly they did at Abu Ghraib. So we learn all about that from the Nazis. Americans are not Nazis and they’re not doing exactly what Nazis did at Abu Ghraib, but they’re doing things that we have to object to and take a strong stand against.

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: We almost hear nothing about doctors at Abu Ghraib.

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: Well, we did. There have been some very good efforts and besides my own article. And I spoke to some military people in which I was pleased to hear that one of the leading military medical officers said, after my article appeared, they initiated a kind of investigation of what was going on. So they read those articles. There have been other doctors who have systematically approached these issues and there’s a book coming out now soon on the whole matter. So I think now that the issue of what doctors are doing, and have done, although — yes, it has been made public, there have been articles in the New York Times about it — but it will become more so.

There’s something about doctors engaging in torture or destructive behavior that strikes people as more dreadful than other groups. It doesn’t mean doctors are better than anyone else. They’re as good or bad as other people. But doctors are committed to be healers, and however they may fall prey for money and status and all that, we expect them — we expect ourselves as doctors to remain healers in some primary way. And when instead of being healers, they join in with tortures or killers, that’s a devastating message to any society, and not one that we want to receive in our society.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Dr. Lifton, you’ve been a doctor for more than half a century. You’ve written books on the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on the Nazis, on Vietnam, Iraq. What gives you hope right now?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: What do I hope right now?

AMY GOODMAN: What gives you hope? Do you think things are getting worse or better?

ROBERT JAY LIFTON: People have asked me — I’ve studied all these draconian events, I confess to it. And people say, “what’s your view of human nature after studying Hiroshima, Nazi doctors, Vietnam?” And my answer is something like, there’s no inherent human nature that requires us to kill or maim. We can go either way. We have the potential for precisely that behavior of the Nazis or of what we did in Vietnam, or of some kind of more altruistic or cooperative behavior. We can go either way. And I think that confronting these extreme situations is itself an act of hope because in doing that, we are implying and saying that there’s an alternative. We can do better. In each of my studies, I end up with an alternative view and something one has learned from that event that can tell us about better possibilities.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, renowned psychiatrist now teaching at Harvard Medical School. His latest book is one he edited with Richard Falk and Irene Gendzier called Crimes of War: Iraq.

Media Options