Related

Topics

Guests

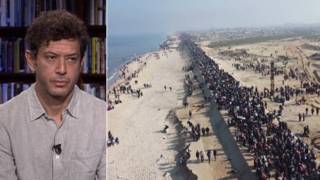

- Juan Coleprofessor of history at the University of Michigan. He runs an analytical website called Informed Comment where he provides a daily roundup of news and events in Iraq and elsewhere in the Arab world. In his new book, Juan Cole steps back from his widely regarded analysis of contemporary politics to chronicle the first Western invasion of the Middle East since the Crusades. Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East is a history of France’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, a conquest that still has repercussions today.

As President Bush seeks $196 billion for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, we speak to Juan Cole about Iraq war and whether the war could spread to Iran and Turkey. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: President Bush has asked Congress for another $46 billion to fund the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The request brings this year’s total to more than $196 billion, by far the highest amount since the 9/11 attacks. If the trend continues, war funding could top $1 trillion by the time Bush leaves office. By some measures, that amount would exceed the cost of the Korean and Vietnam wars combined.

The record-high request comes as the drumbeat continues for opening a new war with Iran. Vice President Dick Cheney warned Sunday that Iran faces “serious consequences” over its nuclear program and alleged role in Iraq. His comments came days after President Bush spoke for the first time of “World War III” if Iran obtains the knowledge necessary to make a nuclear weapon. And the threat has been bipartisan: the three leading Democratic presidential candidates — Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama and John Edwards — have all declared that no option is off the table to stop Iran’s nuclear program.

Juan Cole is a professor of history at the University of Michigan. He runs an analytic website called Informed Comment, where he provides a daily roundup of news and events in Iraq and elsewhere in the Arab world. In his new book, Juan Cole steps back from his widely regarded analysis of contemporary politics to chronicle the first Western invasion of the Middle East since the Crusades. Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East is a history of France’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, a conquest the still has repercussions today.

Juan Cole joins us now from Ann Arbor, Michigan. Welcome to Democracy Now!, Professor Cole.

JUAN COLE: Thanks so much, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s great to have you with us. Before we go back in time, can you talk about this latest news, the latest threats against Iran? How serious are they? Do you think a U.S. war with Iran is imminent?

JUAN COLE: Well, I think the Cheney camp in the Bush administration very much would like to bomb the nuclear research facilities, which, as far as we know, are civilian facilities near Esfahan. And what has been leaked from their office is that they’ve talked about various stratagems for getting up such an attack and that they have been blocked so far by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and by Secretary of State Condi Rice.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about the shifting rationale? I mean, we saw in the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq, Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction — or was it Saddam Hussein was a tyrant? — that didn’t fly with the U.S., so they went with WMD, and Saddam Hussein didn’t have WMD. We hear about the nuclear issue, and then we hear about the shifting rationale, that the American people see it as too similar to the missing WMD in Iraq, so that the rationale would be that Iranian soldiers are fighting in Iraq and killing U.S. soldiers.

JUAN COLE: Well, the most disheartening thing for the Cheney war camp must be that a recent poll shows that they’ve actually managed to convince the vast majority of Americans that Iran is trying to get a nuclear bomb and that Iran is actively killing U.S. troops in Iraq. Neither thing is actually in evidence. They’re possible, but it hasn’t been proven. But most Americans have accepted this story. And yet, 78 percent of Americans say that they don’t want a U.S. attack on Iran. So, so far, all of the rationales that they have trotted out and trumpeted through the media for attacking Iran have not been sufficient to convince the American people that action is necessary.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Cole, I want to ask you about Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s visit to the U.S. last month. He spoke at Columbia University in a highly contested address. Many who criticized Columbia for hosting the event later praised Columbia President Lee Bollinger for his harsh introduction to Ahmadinejad.

LEE BOLLINGER: Frankly — I close with this comment — frankly and in all candor, Mr. President, I doubt that you will have the intellectual courage to answer these questions. But your avoiding them will, in itself, be meaningful to us. I do expect you to exhibit the fanatical mindset that characterizes so much of what you say and do.

Fortunately, I am told by experts on your country that this only further undermines your position in Iran, with all the many goodhearted intelligent citizens there. A year ago, I am reliably told, your preposterous and belligerent statements in this country — was at one of the meetings of the Council on Foreign Relations — so embarrassed sensible Iranian citizens that this led to your party’s defeat in the December mayoral elections. May this do that and more.

I am only a professor — I am only a professor who is also a university president. And today I feel all the weight of the modern civilized world yearning to express the revulsion at what you stand for. I only wish I could do better. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Columbia University President Lee Bollinger. Professor Cole, your response?

JUAN COLE: Well, my own analysis is that Bollinger solved a problem that he had, which was that his — one of his deans had invited Ahmadinejad the previous year to speak at Columbia, and Bollinger had shot that down. His faculty were angry at him for suppressing this man’s freedom of speech in the United States. And so, I think he felt he had to extend the invitation this year.

On the other hand, he wants to rebuild the area around Columbia University. He wants to put a new theater district up there. He needs the help of the New York real estate community, many of whom are warm supporters of Israel and who would be offended by Ahmadinejad’s invitation. So I think he solved the problem by inviting Ahmadinejad, and so mollifying his faculty, and then attacking Ahmadinejad, and so mollifying his real estate backers.

AMY GOODMAN: What about Ahmadinejad’s power in Iran?

JUAN COLE: Well, Ahmadinejad is a ceremonial president. He is a little bit more active, has stronger links to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps than his predecessor, Mohammad Khatami, who, by the way — the previous president of Iran — has upbraided Ahmadinejad for his comments regarding Holocaust denial. So Ahmadinejad is — he is not commander-in-chief of the armed forces. He can’t order anybody to kill anybody. He can’t launch a war. He can’t launch missiles. Those powers are vested in the supreme jurisprudent, the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Ahmadinejad can, you know, cut the ribbons and open bridges and things like that. So the American right’s fascination with him is entirely misplaced, and it’s because he’s a quirky character and he has objectionable views, and so it’s easy to use him to demonize Iran.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you about General Petraeus’s report. General Petraeus spoke before Congress last month. He accused Iran of waging a proxy war inside Iraq.

GEN. DAVID PETRAEUS: In the past six months, we have also targeted Shia militia extremists, capturing a number of senior leaders and fighters, as well as the deputy commander of Lebanese Hezbollah Department 2800, the organization created to support the training, arming, funding and, in some cases, direction of the militia extremists by the Iranian Republican Guard Corps Quds Force. These elements have assassinated and kidnapped Iraqi governmental leaders, killed and wounded our soldiers with advanced explosive devices provided by Iran and indiscriminately rocketed civilians in the international zone and elsewhere. It is increasingly apparent to both coalition and Iraqi leaders that Iran, through the use of the Quds Force, seeks to turn the Iraqi special groups into a Hezbollah-like force to serve its interests and fight a proxy war against the Iraqi state and coalition forces in Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s General Petraeus testifying before Congress. Professor Cole, your response?

JUAN COLE: Well, the whole story doesn’t make much sense to me. The main backers of Iran in Iraq are the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq, which was formed in Iran at the suggestion of Ayatollah Khomeini by Iraqi Shiite expatriates, and has a paramilitary, the Badr Corps, which is trained by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. The Badr Corps and the Supreme Council are America’s closest allies among the Shiites of Iraq.

I think this is really a jealous girlfriend story. I think the U.S. wants the fundamentalist Shiite parties and militias for itself, doesn’t want to have to compete with Iran for their affection for clientelage, and so is slamming Iran as a way of driving a wedge between them. All of the Iranian personnel that have been kidnapped by the United States, detained by the United States, have been found in territory of U.S. allies — Abdul-Aziz Al-Hakim, the leader of the Supreme Council, or up in Erbil among our Kurdish allies. So the idea that the Iranians are building up rogue units of the nativist Mahdi Army, who are slum kids in Iraq, don’t like Iran — I don’t know — doesn’t strike me as very likely. And I think that the U.S. military is getting bad intelligence on these things from some of its contacts, including the cult-like terrorist organization, the Mujahideen-e-Khalq, which Saddam used against Iran and which the Pentagon is still using against Iran.

AMY GOODMAN: And the fact that there are more Saudi fighters in Iraq than Iranian, but that is almost never raised, either in the press or by the administration?

JUAN COLE: To my knowledge, the United States has never captured any Iranian with arms. There were 136 foreign detainees, the last we knew. There are 24,000 Iraqi ones. And the 136 contain no Iranians at all. 45 percent of them, earlier in the summer, were Saudis. I think that proportion has changed, but it’s such a small number. But, in any case, there is no proof of any actual Iranian military activity inside Iraq whatsoever.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, on the issue of Iran, the resignation of the nuclear negotiator, Ali Larijani, what is the significance of this?

JUAN COLE: Well, it’s very bad news. In many ways, it’s a sign that President Ahmadinejad, who does have the power to appoint ambassadors and some of the diplomatic corps in conjunction with the approval of the Supreme Leader Khamenei, is gradually putting his people into place. Larijani was a very experienced diplomat, well liked among his European interlocutors, and is being replaced by someone of far less experience who, however, is close to Ahmadinejad. So, it’s cronyism. I think it’s a very bad move on Iran’s part and probably worsens their posture with regard to these negotiations over their nuclear program.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break. When we come back to Professor Cole, we’re going to talk about Turkey, Iraq and what the invading army of Napoleon in Egypt has to do with today. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. Juan Cole’s book is called Napoleon’s Egypt. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Our guest is Professor Juan Cole, professor of history, University of Michigan. He’s joining us from Ann Arbor from the campus. He runs an analytical website called Informed Comment, and has written a new book called Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East.

Let’s go today’s top story: tension remaining high on the Turkish-Iraq border, following the killing of 17 Turkish troops by Kurdish militants over the weekend. How significant is this?

JUAN COLE: Well, it’s extremely significant. I mean, imagine what would happen in this country if a guerrilla group based in a neighboring country came over the border and killed 17 U.S. troops. That would be a war. And the Kurdish guerrilla movement, the Kurdish Workers Party, based now in Iraq, but originally from Eastern Anatolia, from the Turkish regions, is conducting a guerrilla war against the Turkish military. It is being given safe harbor by Kurdish politicians on the Iraqi side.

And, in essence, the United States has created this situation in which a NATO ally — people forget Turkey fought alongside the United States in Korea; it’s got troops in Afghanistan — a NATO ally of the United States is being attacked and its troops killed by a terrorist organization, so designated by the State Department, that essentially has U.S. auspices. The U.S. is responsible for security in Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: And how connected is the U.S. to the PKK, or is it at all?

JUAN COLE: Well, the United States doesn’t like the PKK and doesn’t have much connection to it, but the United States has allied with the Iraqi Kurdish leaders, who are the most reliable allies of the United States in Iraq: Massoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani. And Barzani, in particular, it seems to me, just de facto, is giving harbor to, giving haven to, these PKK guerrillas. So the United States needs Barzani and needs his support. He’s doing an oil deal with Hunt Oil, which is close to the Bush administration. His Peshmurga paramilitary is the backbone of the most effective fires of the new Iraqi army. They do security details in other cities like Mosul and Kirkuk. So the U.S. really desperately depends on the Kurdistan Regional Authority and its paramilitary and can’t afford to alienate Barzani. And since Barzani is — behind the scenes seems to kind of like the PKK and does — giving them a haven, the U.S. is politically complicit in these attacks.

AMY GOODMAN: What is the deal with Hunt Oil?

JUAN COLE: Well, Hunt Oil, which is, I think, losing its bids in Yemen, is desperate for a new field to develop, and they are exploring a partnership with the Kurdistan Regional Authority in northern Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: And the issue of the U.S. Congress taking a vote within one of its committees, Foreign Relations Committee, that Turkey was involved in a genocide against the Armenians, the significance of that vote, though it’s expected to fail at a congressional level with the whole Congress voting, and how it has played in Turkey, leading to the parliament vote to invade northern Iraq?

JUAN COLE: Well, I really here would underline that, as a historian, I think it’s important that everybody understand the horrible things that were done to the Armenians during World War I. On the other hand, it’s my duty also to try to understand the Turkish contemporary response, which is that the United States has made enormous trouble for this close ally. Turkey has put itself out over the last decades to help the United States. It was an ally in the Cold War. It was an ally in the Gulf War.

And in return, the United States seems to have told Turkey, “Drop dead,” I mean, they invaded Iraq against Turkish advice. They have unleashed Shiite fundamentalism, Sunni fundamentalism, Kurdish separatism on Turkey’s doorstep. There is now a resurgence of the PKK and terrorism against Turkish citizens. And now, on top of all this trouble the United States is making for the Turks, the U.S. Congress was set to condemn the Ottoman government of Turkey, the predecessor government to the present one, for this genocide against the Armenians.

So, the Turks are hurt and confused. In Bill Clinton’s last year, 56 percent of the Turkish public thought well of the United States. That number is down to 9 percent. So it’s not entirely clear what motive the United States has in so alienating a country that has been a valued and close ally.

AMY GOODMAN: The question of history informing what’s happening today — Professor Cole, you’ve just written a book, Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East. Give us the context of that time and how that has parallels to today.

JUAN COLE: Well, in a way, it’s a remarkable story. The young French republic, having made this revolution and proclaimed the rights of man, was under attack by a number of foreign enemies, monarchies, that opposed the republican principle, among them England. And the British had naval superiority in the Mediterranean. They had a building colony in India, where they had won a war with the French. The French were kicked out of India by the British.

And so, Napoleon Bonaparte, at the time when he was still a general — hadn’t come to power — came up with this idea of a strike at Ottoman Egypt as a way of creating a French Mediterranean, of blocking British naval superiority and of threatening the British colony in India. And so, he convinced the French government to fund this massive expedition, 50,000 men, and he went off to Egypt — of course, easily conquered it. It was a small country compared to France. But then, the British sank his fleet or chased it away, and the French soldiers were trapped in Egypt, and they faced repeated insurgencies and attrition.

Bonaparte had proclaimed that he was going to liberate the Egyptians from tyranny, that he was going to install a democratic government. His officers expressed confidence in their memoirs that the Egyptians would be grateful for this bestowal of liberty by a Western power. And so, there are many resonances to today’s quagmire in Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: The graffiti of French soldiers still seen on the pyramids?

JUAN COLE: Well, it was an expedition that deeply marked modern Egypt. It was the time when the Rosetta Stone was discovered, although not deciphered until much later, that allowed the recovery of ancient Egyptian civilization. But it was also a very brutal occupation. Bonaparte, if a village rebelled, would order it burned, its men killed. And he did this over and over again. The letters are very clear about the brutality of the policy. It was a take-no-prisoner kind of policy in many instances. And even his own officers began to complain that Bonaparte was increasingly acting like the old French monarchy in an arbitrary way or like an Oriental potentate. And Bonaparte himself attempted to fool the Egyptians into thinking that Enlightenment French deism, which rejects the Trinity and was opposed to the pope and the Roman Catholic hierarchy, was essentially a form of Islam, so the Egyptians shouldn’t mind so much being ruled by the French.

AMY GOODMAN: What about how the role of women changed under Napoleon — Egyptian women?

JUAN COLE: Well, under Napoleon, many restrictions on women were lifted. The Egyptian male chroniclers complained bitterly that the French started going out with women, they appeared publicly, they went to dances together. From an Egyptian Muslim point of view, this was licentiousness and libertinism. But they do admit that the women themselves became intrigued with this new freedom of movement, that they were walking in the streets and laughing and unveiled. And the male chroniclers were fit to be tied by this change. But, it should be remembered, most Egyptian women were peasants, They were not much affected by French policy. And a lot of Egyptian women were victimized by the French, either as mistresses or even as slaves. The French bought women as slaves and used them that way. So it was a mixed picture.

AMY GOODMAN: What, Juan Cole, caused the French eventually to leave Egypt?

JUAN COLE: Well, Bonaparte himself tried to break out of his box, once the fleet was destroyed, by taking Syria, but he couldn’t succeed in that. The Ottoman forces fought him off, and he therefore slipped out of Egypt after about a year. And he had done propaganda back in France that his victories were glorious. So he came back and used his Egyptian so-called victory as a platform for making a coup and coming to power as first consul. But his troops were stuck in Egypt. He kind of abandoned them for another two years. Ultimately, the British and the Ottomans made an alliance, and the British gave naval support to an Ottoman expeditionary force that defeated the French. And the soldiers were transported back to France on Egyptian — I’m sorry, on British vessels in a rather humiliating way.

AMY GOODMAN: How long was the occupation?

JUAN COLE: Three years.

AMY GOODMAN: What about parallels to today? Do you see parallels to how the U.S. would leave?

JUAN COLE: Well, no, because in that time it was a multi-polar world and France had lots of enemies, including the British and the Russians, who could ally with the Ottomans, and the local Muslim forces found Western Christian allies against the French. In our day, it’s a unipolar world; there’s only one superpower. There’s no other country that would be willing to help the Iraqi guerrilla movement against the United States in an open sort of way. And so, the United States, in some ways, is in a much better position than the French were.

But it still faces many of the same problems: lack of legitimacy, the rejection of a Muslim people ruled by essentially a Christian nation, an ongoing attrition and insurgency, volunteers coming from Mecca, which happened also against the French. So the United States’s position in Iraq is tenuous. It’s not as tenuous as the French position had been in Egypt, but it just goes to show that the course of Western colonialism in the Middle East doesn’t flow smoothly.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you see the war expanding?

JUAN COLE: The Iraq war could expand very easily. I mean, we don’t know, of course, the future, but now we begin to see that the Kurdish separatism in northern Iraq is causing severe tensions and possibly military conflict with Turkey. There’s a possibility of increased Sunni volunteers, if the Shiites were to massacre any large number of Sunni Arabs. It especially seems likely that the U.S. will gradually draw down troops in the next two and three years. If it leaves behind it substantial instability and there are massacres, it could draw in the neighbors. You could have a proxy war. And these things are dangerous to the world economy, because the Persian Gulf is the source of a very substantial amount of the world’s energy, and that energy production could be interrupted by such a guerrilla war. So it’s a very, very dangerous situation.

AMY GOODMAN: And the news from Lebanon that a high-ranking leader of Hezbollah has warned the United States not to set up any military bases inside Lebanon, Hezbollah saying it would consider such move a hostile act, and the U.S. increasing their military assistance to Lebanon to $270 million, more than five times the amount they provided a year ago?

JUAN COLE: Well, to tell you the truth, Amy, I think the idea of putting a U.S. military base in Lebanon, which is an unstable country and has a very large Shiite militia, is a brain-dead idea, and I can’t imagine that the Lebanese government itself will be so stupid as to go forward with this. And up until recently, of course, Hezbollah, which opposes this plan and which has a substantial number of deputies in the Lebanese parliament, was part of a national unity government. That’s broken down for the moment. It may come back. It seems to me that the politics of that move would be awfully fraught.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you very much for being with us, Juan Cole, professor of history, University of Michigan. Thanks for joining us from Ann Arbor. His blog is called Informed Comment. His new book is Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East.

Media Options