Related

Topics

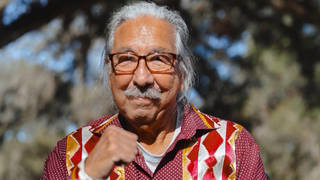

Guests

- Francisco Goldmanacclaimed American-Guatemalan novelist. He is the author of three novels, including The Long Night of White Chickens. His latest book is his first nonfiction work. It’s called The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop?

General Otto Pérez Molina is slightly trailing in polls ahead of Sunday’s run-off election in Guatemala. The acclaimed Guatemalan novelist Francisco Goldman joins us to talk new evidence linking Gen. Pérez Molina to the 1998 murder of a beloved Guatemalan human rights activist. Goldman writes about the case in his first book of non-fiction, “The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop?” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In Guatemala, millions of voters head to the polls on Sunday for the second round of general elections to pick a new president. The runoff vote pits three-time center-left candidate Álvaro Colom against hard-line former army general Otto Pérez Molina.

General Pérez Molina, the ex-head of army intelligence, has promised to expand the police force by half and to use the military to fight crime. He closed out his campaign on Monday in the city of Villa Nueva.

GEN. OTTO PÉREZ MOLINA: [translated] We want a Guatemala with justice, not inequality. I tell you, I am convinced and have no doubt that there will be a change on November 4th, with a strong hand, mind and heart, with “Cayo” Castillo and Otto Perez, the best option.

AMY GOODMAN: General Pérez Molina commanded troops in one of Guatemala’s most violent areas, has been implicated in a number of political crimes. Now, new evidence suggests that he may have orchestrated the 1998 murder of the beloved Guatemalan human rights activist, Bishop Juan Gerardi.

Known in Guatemala as “the Crime of the Century,” Bishop Gerardi was bludgeoned to death in his garage in Guatemala City, April 26, 1998. Two days earlier, he had released a four-volume report that found the Guatemalan army primarily responsible for the overwhelming number of deaths and disappearances of as many as 200,000 civilians over four decades.

Gerardi’s murder set off global repercussions in political and human rights circles. The case was one of the most sensational and controversial in Latin America’s history. Three army officers and a priest were ultimately convicted of the crime.

We’re now joined by author Francisco Goldman, who has spent the last seven years investigating the case. His book is called The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? Goldman provides a detailed account of Gerardi’s murder and an exhaustive investigation into who was responsible. Francisco Goldman is an acclaimed Guatemalan American novelist. He is the author of three novels. We welcome you to Democracy Now!

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: Thank you, Amy. It’s a pleasure to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: This is nonfiction, this one, your latest book?

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: This is nonfiction, but written almost in the form of a novel. It’s a narrative chronicle of a nine-year legal case, really.

AMY GOODMAN: This is a major charge you are making on this eve of the Guatemalan election.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: It’s a charge that I’m repeating, because I was led to it by two of the major sources for me throughout the book. It’s funny, because it’s actually only a few pages of the book where this charge emerges, when the key — first the key witness in the case, apparently a park vagrant, who was situated outside the parish house where the murder took place the night of the murder, but who was actually an army intelligence agent who had been planted there and, in fact, had a role in the murder.

AMY GOODMAN: The vagrant?

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: The vagrant, Ruben Chanax, who years later, he was a key witness when the case finally went to trial. And I tracked him down when he was living in Mexico City as a semi-protected witness and working in a taco stand. And in the course of our conversations, when we went over the case time and time again, every detail of the case, it emerged that at the crime scene — you know, we know that the crime was being monitored by three military officers who were sort of overseeing events from a little store nearby the church that night. He had, in the legal case, identified one, Colonel Lima Estrada, one of the men who eventually was imprisoned, but he repressed the names of two, for his own reasons, including staying alive. And he told me that one of those men was General Otto Pérez Molina.

Now, just him saying that wasn’t really enough; I needed obviously confirmation. The confirmation for me came from the most important source I had, a man named Rafael Guillamón, a former Spanish intelligence agent who headed the U.N. mission’s internal investigation into the Gerardi murder. And when he interrogated this Chanax, this vagrant, two days after the murder, he first heard it from him. Now, this investigation was conducted for the U.N.’s internal knowledge, not to share with prosecutors, and so it stayed secret all these years. And then he had even more proof.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain the significance of Bishop Gerardi and the significance of the report that he released.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: When the '96 peace accords, which ended the 36-year war, were signed between — the U.N.-sponsored accords between the Guatemalan guerrillas, who were in a quiescent role, and the victorious Guatemalan army, the army was able to dictate, among other things, a blanket amnesty for all human rights crimes that had occurred during that war, in which 200,000 civilians were slaughtered. It also allowed for a U.N. sort of truth commission that would be allowed to look into the past, but wouldn't be able to name names, name military units who were responsible, and so forth.

And Bishop Gerardi thought that this kind of covering-up of the truth was not going to be healthy or good for Guatemala, and he sponsored his own — the Catholic Church, through the Archdiocese Office of Human Rights, sponsored their own human rights report. And as the Church, they were the only organization in the country, through the parishes, that could reach into every community. And he trained 700, you know, pretty humble people, people from local churches, to go out into these communities, into these highland villages that were so shielded off by speaking, you know, 16 different Mayan languages and traumatized by years of violence, massacres. There is such a thick taboo against speaking out and such fear of outsiders, but the Church, they’re not seen as outsiders. So they went in there for years and collected testimonies.

And on April 24th, two days before his death, he released the most unprecedented, extraordinary four-volume report, in which he managed to identify, for example, 400-plus of the 600 massacres we now know occurred in the war. He managed to list — that’s the whole fourth volume — 53,000 of the dead by name, of the 200,000 people we know that died. And he found the army responsible of 80 percent of the crimes, the guerrillas only 5 percent. He made it — he did name names and military units and made it clear that if the amnesty could ever be breached, he would make this documentation available to prosecutors and to families seeking justice. Now, this was an unbelievable impertinence. When the army had signed the peace accords, they had never expected to have to put up with something like this. And so, they obviously decided they had to do something.

Now, the real question, why it’s the art of political murder, is the question everybody asks, is why do they kill him two days after the report comes out, not, say, days before? And the answer to that, right, gets to the whole institution of impunity in Guatemala. When you know you don’t have to face justice, when you’ve never faced justice before, that gives you sort of, you know, the equivalent of what Virginia Woolf said to a fiction writer was “a room of one’s own,” you know, that freedom of imagination to dream up an extraordinary crime.

And what this crime was, was pure theater. They rigged up a theatrical event that involved a man with no shirt stepping out of the garage after Bishop Gerardi had been murdered; the vagrant planted there to see him, who had probably taken part in the murder; immediately, in all different sophisticated ways, rumors coming out that it had been a homosexual crime of passion, which resulted —

AMY GOODMAN: By a priest.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: By a priest. A corrupt prosecutor, corrupt judges, corrupt media, everybody contributing to this farce. And the story of the book is how this was — what should have been, for the government, a slam-dunk case to pin the whole case on this poor, pathetic priest who shared Bishop Gerardi’s parish house. You know, they claim that he had sicked his dog, and they claim they found signs of dog bites in Bishop Gerardi’s skull, and it was ridiculous.

But in Guatemala, this kind of theatrical crime would ordinarily succeed, and would have if not for the efforts really of the young people portrayed in this book, young secular people in their twenties within the Church, who formed their own investigative unit, named themselves “the untouchables.” And it’s just extraordinary. If it hadn’t been for the efforts of these four young guys and the small team of lawyers at the Church, who, through their own detective work, brought in the first important witnesses in the case and miraculously succeeded in derailing this phony prosecution.

And then, after that, finally — this is a case that saw more than 10 people related to the case murdered, two prosecutors chased into exile, judges chased into exile, countless witnesses in exile. But finally, through the most extraordinary bravery of a handful of people, the convictions managed to go through. There was a historic trial. It was the first time Guatemalan military officers had ever been found guilty of taking part in a state-sponsored, politically motivated execution.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, General Otto Pérez Molina is running for president.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: He’s running for president, and when these accusations emerged in the press, because this is just a few paragraphs, but back in June a Guatemalan newspaper ran them. And he immediately began to get himself in trouble with all kinds of, well, lies, right? First, he said I had written my book because I was in the pay of another politician. Later he accused me of being part of a narco campaign of defamation and political assassinations directed against him.

Then he said — for instance, he tried to say, “I have no knowledge.” You know, when he responded to what had appeared in the paper, he said, “I don’t know Captain Lima,” one of the imprisoned military men. Well, we knew from the U.N. that he and Captain Lima were constantly having cellphone calls when Lima was in prison. And the funny thing is, people in Guatemala immediately started to email the newspaper, giving details of the 30-year relationship between Captain Lima and Pérez Molina. So why did he lie about this?

And even more importantly, the U.N. mission investigator told me that — because Pérez Molina claimed that he was in Washington, D.C. the week the murder happened and that he had a passport that showed this. But the U.N. investigator told me, pay no attention to his passports. He is a military intelligence person. He uses multiple passports, and we know that three nights after the murder, he had dinner — Pérez Molina had dinner with the U.N. mission chief, Jean Arnault, who wanted to sound him out about his theories about the murder, because he’s an intelligence chief. And he thought this would never come out. And he thought he had an alibi. But then, even after this came out, a Guatemalan paper went and investigated, and they found that he had seven passports registered in his name, confirming the U.N.'s skepticism about his claims, and so forth. And since then, since these kinds of allegations came out, he has ducked his last three debates with his opponent, because they think he's afraid of answering questions about this case and other crimes, and his poll numbers have started to dip.

And just yesterday — this is very important — just yesterday, it came out and broke, and it’s already been picked up by international wire services, two reporters from El Periodico, the same newspaper, have discovered that Pérez Molina’s campaign has links to narcos. And they wanted to publish this information, and they immediately began to get death threats, and the paper was under a lot of pressure. And they’ve had to go to the Office of Human Rights basically to ask for help and protection, and want to get this story out. So this just broke yesterday.

AMY GOODMAN: When you say “narcos,” you mean…?

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: The narco cartels, because what’s at stake here, right — it’s important for people to understand, what’s amazing about this case is the bridge between 1980s violence and 21st century violence.

AMY GOODMAN: Over 50 deaths of political activists and candidates leading up to this election on Sunday.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: We have 15 seconds.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: OK. Well, military intelligence used to fight guerrillas. Right now, with political power, it’s all about organized crime, and that’s what they’re trying to hold onto. And that’s the faction, that’s the kind of power that General Pérez Molina is trying to legitimize.

AMY GOODMAN: Francisco Goldman’s book is called The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed the Bishop? I want to thank you very much for being with us.

FRANCISCO GOLDMAN: Thank you. It was a pleasure.

Media Options