Related

Guests

- Tara McKelveyauthor of the book “Monstering: Inside America’s Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War.” She is a senior editor at “The American Prospect” and a research fellow at the NYU School of Law’s Center on Law and Security.

This past Saturday, the Democrats chose retired Army Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez to give their weekly radio address. According to the ACLU, Sanchez urged his troops to “go to the outer limits” to extract information from prisoners. Previously released documents have linked Sanchez to the use of army dogs during interrogations. We speak with Tara McKelvey, author of Monstering: Inside America’s Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War. [includes rush transcript]

Every Saturday, the President of the United States gives a radio address to the nation. It is followed by the Democratic response, usually given by a House or Senate Democrat. It may have surprised some that this past Saturday the Democrats chose retired General Ricardo Sanchez to give the address.

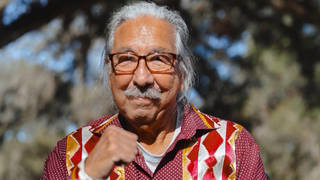

- Gen. Ricardo Sanchez (Ret.)

According to the ACLU, documents show Army Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez, the former top U.S. military commander in Iraq, urged his troops to “go to the outer limits” to extract information from prisoners. Previously released documents have linked Sanchez to the use of army dogs during interrogations.

Democracy Now! interviewed Janis Karpinski in October 2005. She was the only military officer to be disciplined after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke. She said she was scapegoated. She served under General Sanchez and talked about his role in, among other practices, ghost detainees.

- Janis Karpinski, interviewed on Oct. 26th, 2005. [Click for full interview]

Univeristy of Wisconsin Professor Alfred McCoy, the author of “A Question of Torture,” spoke to Democracy Now! in February 2006 about General Sanchez.

- Alfred McCoy, interviewed on Feb. 17th, 2006. [Click for full interview]

We are joined today from Washington, D.C. by Tara McKelvey, author of “Monstering: Inside Americas Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Every Saturday, the President of United States gives a radio address to the nation. It’s followed by the Democratic response, usually given by a House or a Senate Democrat. It may have surprised some that this past Saturday the Democrats chose retired General Sanchez to give the address. That’s retired Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez.

LT. GEN. RICARDO SANCHEZ: For as long as we have troops in Iraq, the American people must insist that our deploying men and women are properly trained and properly equipped for the missions they will be asked to perform.

The funding bill passed by the House of Representatives last week with a bipartisan vote makes the proper preparation of our deploying troops a priority and requires the type of shift in their mission that will allow their numbers to be reduced substantially. Furthermore, the bill puts America on the path to regaining our moral authority by requiring all government employees to abide by the Army Field Manual on interrogations, which is in compliance with the Geneva Conventions. America must accept nothing less.

AMY GOODMAN: According to the ACLU, documents show Army Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, the former top US military commander in Iraq, urged his troops to “go to the outer limits” to extract information from prisoners. Previously released documents have linked Sanchez to the use of Army dogs during interrogations.

Democracy Now! interviewed Janis Karpinski in October of 2005. She was the only military officer to be disciplined after the Abu Ghraib scandal broke. She said she was scapegoated. She served under General Sanchez and talked about his role in, among other practices, ghost detainees.

COL. JANIS KARPINSKI: We were directed on several occasions, and directed through the CJTF-7, through General Fast or General Sanchez, by — the instructions were originating at the Pentagon, from Secretary Rumsfeld, and we were instructed to hold prisoners without putting their — giving — assigning a prisoner number or putting them on the database, and that is contrary to the Geneva Conventions. We all knew it was contrary to the Geneva Conventions. And we were told that this —- these instructions were being given by Secretary Rumsfeld, and -—

AMY GOODMAN: Who told you that?

COL. JANIS KARPINSKI: Colonel Warren and General Fast, the intel officer for General Sanchez, and General Sanchez himself.

AMY GOODMAN: General Fast is General Barbara Fast?

COL. JANIS KARPINSKI: General Barbara Fast. And we were told that these instructions were for specific individuals, and they were a special case. And we would hold them without assigning a prisoner number until they were — until an order was given on how to handle them.

AMY GOODMAN: So that the International Committee of the Red Cross would not know that they exist, would not ask to see them?

COL. JANIS KARPINSKI: Correct. Now, they didn’t — the ICRC would not look for specific prisoners unless there was a reason or a number provided to them, for example, and because there was no communication between prisoners and family members, at least not from Abu Ghraib, because security detainees, as we were told, they fit into a different category. So, it would be unusual for the ICRC to be looking for a specific prisoner by a prisoner number. They would come in, they would look at conditions, they would talk to individuals. Sometimes they would randomly select numbers, but the purpose of not putting them on any database is to keep them from being known.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Brigadier General Janis Karpinski was demoted to colonel. University of Wisconsin Professor Alfred McCoy, the author of A Question of Torture, spoke to Democracy Now!

in February of 2006 about General Sanchez.

ALFRED McCOY: In September of 2003, General Sanchez issued orders, detailed orders, for expanded interrogation techniques beyond those allowed in the US Army Field Manual 3452, and if you look at those techniques, what he’s ordering, in essence, is a combination of self-inflicted pain, stress positions and sensory disorientation. And if you look at the 1963 CIA KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation Manual, you look at the 1983 CIA Interrogation Training Manual that they used in Honduras for training Honduran officers in torture and interrogation, and then twenty years later, you look at General Sanchez’s 2003 orders, there’s a striking continuity across this forty-year span in both the general principles: this total assault on the existential platforms of human identity and existence, OK, and the specific techniques, the way of achieving that, through the attack on these sensory receptors.

AMY GOODMAN: That was University of Wisconsin Professor McCoy. We’re joined today from Washington, D.C., by Tara McKelvey. She’s author of a new book; it’s called Monstering: Inside America’s Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War. Tara is also senior editor at the American Prospect and a research fellow at New York University’s Center for Law and Security. Welcome to Democracy Now!, Tara McKelvey.

TARA McKELVEY: Thanks for inviting me.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s good to have you with us. Were you surprised the Democrats chose retired General Sanchez to give their Saturday radio address?

TARA McKELVEY: Yeah. I was at home over the long weekend, and I got an email about Sanchez’s doing the radio address, and I just kept staring at the email and thinking, like, how could they do this? I was really, really surprised by it.

AMY GOODMAN: You write about him extensively, among many other issues, in Monstering. Talk about his significance.

TARA McKELVEY: Well, one of the things that he did was he spoke a lot with General Geoffrey Miller, who had come over from Guantanamo in the fall of 2003, and they talked about the types of interrogations that would take place at Abu Ghraib. And at that point, Miller had decided that Abu Ghraib would be the central intelligence collection place in Iraq, and it was tremendous pressure on these officers, as well as the entire military, to get what was known as “actionable intelligence” from detainees who were held in Iraq, because there were so many attacks on American troops. And it was in September of 2003 that Sanchez issued a memo that outlined certain guidelines for interrogations. And these included many of the things that had been used at Guantanamo, like sleep deprivation or stress positions.

And when you first hear of these things, you don’t think that they sound so bad, you know, like Giuliani was saying, “You know, I stay awake all the time on the campaign trail. You know, sleep deprivation, what’s so horrible about that?” But the fact is that over a period of time, sleep deprivation, it causes a body to collapse entirely, and a person will die.

As far as stress positions go, again, according to the official guidelines, it can mean something like having a person crouch in a position for no more than, say, forty-five minutes. And the truth of the matter at Abu Ghraib was somewhat different. The stress positions were used for much longer periods of time, and they also encompassed a wide variety of positions, one of which was something called a Palestinian hanging, which is where they have the person’s hands tied behind their back and then they’re suspended from their hands. So then, at a certain point, the person’s shoulders would become dislocated. And according to a lot of people who were at the prison at the time, you could hear people screaming in their cells at night since they were being held in these positions. And in addition, there was this photograph, what was known as “the Iceman.” It was a prisoner named al-Jamadi. Maybe you remember that picture. He actually died while being held in what was known as the Palestinian hanging. So stress positions are anything but benign.

And then, the other thing to remember is that at Guantanamo, you know, however you feel about these interrogation techniques, at Guantanamo they were done under highly controlled circumstances. For instance, the prisoner-to-detainee [sic] ratio at Guantanamo was one-to-one. At Abu Ghraib, the prison was overcrowded. They didn’t have enough people working there. You know, they were getting mortared at night. And the ratio of prisoner to guard at Abu Ghraib was seventy-five-to-one. So these techniques were being introduced in an environment that was utterly chaotic.

AMY GOODMAN: The story of what happened at Abu Ghraib, parts of it have been told again and again. What do you feel, after investigating this extensively, has been missed?

TARA McKELVEY: I think that the conversation about Abu Ghraib has gotten so politicized that there’s people who are willing — for instance, on the left, people want to blame those who are very, very high up in the chain of command, Dick Cheney, you know, Bush. And then, on the other side, administration officials have tried to say that the Abu Ghraib scandal was caused by a few rogue soldiers, a few bad apples, you know, these sadistic guards who were working there at Abu Ghraib. The truth lies somewhere in the middle. It wasn’t simply the Justice Department officials who were, you know, renegotiating the definition of “torture” and the White House officials who were trying to crack down on the detainees in Iraq, and it wasn’t simply these people who had come in and were working as guards at the prison and unleashing their, you know, violent fantasies on these prisoners. It was a combination of the two that came together and created Abu Ghraib.

AMY GOODMAN: You are the first reporter to interview female prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Tell us about them.

TARA McKELVEY: I had first found out that there were female prisoners there sometime in the fall of 2004, and I was completely shocked by it. I thought about the men in the pictures that we had seen that were released in the spring, and I just thought, you know, my god, what do they do to the women? I went over to the Middle East twice, and I interviewed about twenty men, women, and children who had been held at Abu Ghraib, and they told me what had happened to them. I also interviewed, you know, in rooms when I was in a hotel over in the Middle East, I interviewed women who had been held there, and they described the atrocities.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the woman described as Saddam Hussein’s mistress.

TARA McKELVEY: That was another thing about interviewing the former detainees, is at times I wouldn’t know that much about them when I started the interview. By the end of the interview, by the end of the research, I would be often surprised at what had happened in their own personal lives. And this was a case where she was — the woman who I had spoken to was married to a man who was an Iraqi lawyer and who had worked for Saddam Hussein. I spent a long time with him when he talked about the interrogations that he had been subjected to, and I spent a lot of time with her, too. We had tea and, you know, talked about their experiences.

Afterwards, I talked to the Pentagon, and they — one of the Pentagon officials read to me, on background, information about her case study, and he had told me that she was known as a mistress of Saddam Hussein. And I was very surprised by the news. But after hearing that — and then I spoke with her mother many times before and after hearing that — the pieces sort of came together. There’s no question that many of the individuals that I interviewed either had shady pasts or were perhaps involved in things that they shouldn’t have been involved in. But that doesn’t take away from the fact that the interrogation methods and the treatment that prisoners were receiving while they were in detention facilities was wrong and certainly was in violation of the Geneva Conventions.

AMY GOODMAN: Tara McKelvey, I interviewed former Army sergeant and Abu Ghraib whistleblower, Sam Provance, earlier this year, the intelligence analyst who served in Abu Ghraib from September 2003 to the spring of 2004. When he spoke out against the abusive interrogation practices in the prison, he was branded a traitor and reduced in rank. You also write extensively about him in the book. I asked him to describe one of the first alarming incidents he witnessed at Abu Ghraib.

SAMUEL PROVANCE: What had happened was two interrogators had been drinking one night and then went to, you know, the hard sites, to, you know, where they held all the detainees that they interrogate, and went into there under the guise of, you know, we’re here to interrogate this girl. And I guess she was sixteen years old. And, you know, they took her out, but instead of interrogating her, they had plans of molesting her or even raping her. And it may have been the one girl they called jokingly “Fedateen,” because she was really flirtatious with soldiers and supposedly had love letters the soldiers had written her, and she was always — you know, they said that she was always trying to flirt with soldiers and whatnot. And so, anyways, they said these guys had gotten caught, because the MP on duty that night had noticed that something was amiss, and especially when he went by and saw that her shirt was taken off. So, you know, he made a phone call and got the situation under control.

But then came their prosecution, and I was even asked by one of their friends to lie and call Colonel Pappas’s character into question to somehow negate his authority, but, you know, I’m not going to do that. But nothing ended up happening to them. You know, I was told they were given some kind of suspension or some kind of Article 15, but it was basically brushed under the carpet and never heard from again. And then, even later, they denied that anything had even happened at all.

You just didn’t know what was going on there. You know, there were so many different moving pieces and very important and very powerful people monitoring what was going on. I mean, most people think that what happened at Abu Ghraib was just a handful of soldiers, you know, out in the middle of nowhere, some remote outpost, when in reality it was the premier hub of human intelligence, you know, being watched by the highest powers that be. I mean, even before I had gotten there, Donald Rumsfeld had visited there, Paul Wolfowitz, other representatives for other people in our government, as well as our own, you know, Army powers that be, such as General Ricardo Sanchez and General Fast. And there was brass all over the place on the prison itself. I mean, there was more first sergeants and commanders than you could shake a stick at.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Army sergeant and Abu Ghraib whistleblower, Sam Provance, intelligence analyst who served in Abu Ghraib, 2003 to 2004. We’re going to play the full interview later this week, early next week. Tara McKelvey, talk about his significance.

TARA McKELVEY: Sam Provance was at Abu Ghraib, and he was a witness. He had a front-row seat to what was going on. He also told me a lot about sort of the way people lived at Abu Ghraib. He told me about this kind of — this thing they called “robotripping,” which is where they did — they had one of the cells turned into a party room, where they blocked off the bars, you know, with wood so they could have privacy in this room, and they would play rave music and OutKast. You know, I’ve seen the videos, and I remember there was a lot of OutKast. And they would do these drugs, which was basically a combination of Robitussin and then sort of uppers, you know, over-the-counter caffeine pills. And then, you know, according to my sources, it would produce kind of this like LSD effect. And so, they would have these robotripping parties in the prison cell, and this was at Abu Ghraib.

And at these parties, they would sometimes pretend to act out what they were doing to detainees. So I saw videos of them stabbing pretend detainees or kicking them or beating them savagely or pretending to rape other, you know, men.

And this effect of these videos or of this world that they had created was pretty disturbing. And also it sort of gave some sense of the sense of lawlessness that was at the prison at the time. There was very little oversight. People knew stuff was getting out of control, but nobody seemed to really be doing anything to stop it.

AMY GOODMAN: And the formerly unreleased information about the rape of an Iraqi child that you discovered in writing Monstering?

TARA McKELVEY: Yes. I think that one of the things that has been disturbing both for people in the States and for people abroad has been the lack of accountability. And even when there was a lot of evidence that had been collected about crimes that may have been committed at the prison, very little was done to hold these people accountable.

In this one case, there was a witness who had said that a boy had been raped at the prison, and according to the court documents or according to the military investigations, there was even film footage; whether it was a video or pictures, it was never clear. But the investigation — and the investigation was sent over to Justice Department, it was brought up to the highest levels of the government, but it never went anywhere. The person who had been — you know, said that they had actually seen this take place or had heard it from another prison cell was never able to provide enough evidence that they needed to prosecute. The boy himself disappeared. He was sent back into the — you know, into another facility and just was never heard from again. And so, the investigation was never carried through. So despite, you know, compelling evidence, so that at least an investigation should take place, the whole thing fell apart.

And in some sense, on a more global scale, that seems to be what at least administration critics say has happened with the Abu Ghraib scandal, is that in the beginning there was a lot of talk about how we’re going to get to the bottom of this and we’re going to hold people accountable, but, in fact, very little was done to hold people higher up in the chain of command accountable for what had happened there.

AMY GOODMAN: You write, in the last few pages, about an officer at Guantanamo in 2003 and Abu Ghraib in 2004, about the role of psychologists. Were you speaking with Colonel Larry James?

TARA McKELVEY: You mean, was that my source for that interview?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

TARA McKELVEY: Well, I didn’t name him, so there’s a reason that I didn’t do that, but it wasn’t that person that you just mentioned.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about your understanding — in our next segment, we’re going to talk about the role of psychologists — but what you came across, from Abu Ghraib to Guantanamo?

TARA McKELVEY: Well, at Guantanamo they had what were called “biscuit” teams. They had interrogations that were set up with a psychologist or a psychiatrist, along with a doctor who would monitor the interrogations. And the argument for that is that it’s necessary in order to protect the safety of the detainee. The argument against that seems pretty clear: if you’re in a healing profession, it seems contrary to the basic instincts of what you’re supposed to be doing to be helping to devise interrogation plans that are solely designed to inflict pain and suffering on the individual.

AMY GOODMAN: You, Tara McKelvey, got an exclusive interview with Lynndie England, one of the soldiers who went to jail for the abuse of prisoners. What did you learn from her?

TARA McKELVEY: Well, the interview I did with Lynndie England was actually in the brig, in the prison in San Diego. And it was a very difficult interview, because as much as I wanted to, you know, find some common ground with Lynndie England or to find out exactly what had caused her to do the things that she had done, I had sort of in the back of my head the voices of people that I had met who had been held at Abu Ghraib and the stories that they had told me about being hung from cells and the screaming at night and the suffering that they had been subjected to, and I knew that Lynndie England was there when some of those things took place. She has even said to me, in some oblique way to protect her from further prosecution, that she heard about — she heard the screaming at night. And I know from her friends in West Virginia that those experiences gave her nightmares and were quite horrifying. But it was difficult to talk to her and try to find out what had happened more when she showed this certain coldness about those things that had taken place. And she did seem very remorseful, but the remorse seemed to come more from the fact that she was in the brig and that other people were not. And I think that’s what she deeply regretted, that she had ended up in that position and regretted certainly a sequence of events that had brought her there.

AMY GOODMAN: Since you’ve written the book, of course, Judge Mukasey has become the Attorney General of the United States. You write about water torture, about waterboarding. The Attorney General saying he didn’t know if waterboarding was torture, your response?

TARA McKELVEY: Well, first of all, I mean, what is waterboarding? It’s used in different forms. I guess the best way to describe it is the person’s head is tilted back, and maybe sometimes a sponge will be placed in their mouth and water will be poured into it, and they will have the sensation of drowning. I mean, right there, it’s the sensation of drowning. Well, in fact, the lungs of the person who’s being waterboarded are filled with water, so the person is actually drowning.

I had a conversation about this with Rosa Brooks, who’s a professor at Georgetown Law. And like she was saying, if you’re in the middle of a lake, and you’re going under water, and you’re trying to get back up again, and you’re screaming for help, you’re screaming — you know, you’re not screaming, “I am experiencing a simulation of drowning,” you know, you’re screaming, “I’m drowning!” Your lungs are filling with water. So there’s no question about the horrific nature of this technique. I think there is nothing more terrifying than the feeling of suffocation.

As far as his response to it, I find it a bit puzzling. It seems he seems to be a very intelligent man and very well educated, and it’s not that hard to figure out what waterboarding is, and the fact that it is widely described as a torture technique is also not hard to figure out. I think that there was probably something else going on in his reluctance to talk about it.

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you understand is going on today with prisoners? There are over 25,000, it’s believed, held in Iraq alone.

TARA McKELVEY: If you look at what happened at Abu Ghraib and at some of the other detention facilities where detainees were abused, part of the problem was overcrowding and lack of resources. In December of 2003, shortly after the Abu Ghraib photographs were taken, there were about 12,000 prisoners held in Iraq. So that means that today we have more than twice the number of prisoners than we had at that time. Anytime you have that number of people taken into detention facilities, that raises a possibility of arbitrary arrest and detention.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you for being with us. Tara McKelvey’s new book is called Monstering: Inside America’s Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War. She’s a senior editor at American Prospect. When we come back, we’ll go to a psychologist in Boston for the latest on psychologists and their role in interrogations and what the APA, the American Psychological Association, is doing about it.

Media Options