Related

Guests

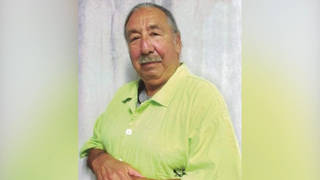

- Cornel Westprofessor of religion and African-American studies at Princeton University, speaking at the 2007 Left Forum in New York City.

Professor, culture critic and social justice advocate Cornel West addressed a panel at the 2007 Left Forum in New York last weekend. West is a professor of religion and African-American studies at Princeton University. West says, “What I would like to see is radical reformism once more become fashionable among young people.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The 2007 Left Forum came to a close Sunday in New York City. Each spring, the forum convenes the largest gathering here in the country of the international left. With close to a hundred panels, three major cultural events, the Left Forum brings together organizers and intellectuals from across the globe.

One of those who spoke was professor, culture critic, social justice advocate, Cornel West. He has been described as one of America’s most vital and eloquent public intellectuals. A professor of religion and African-American studies at Princeton University, Professor West is a critic of culture, now analyst of postmodern art and philosophy, has written and co-authored many books on philosophy, race and sociology. His most recent book is Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism. He addressed a panel at the Left Forum. Cornel West began by talking about the status of the political left in 2007.

CORNEL WEST: What does it really mean to be a leftist in the early part of the 21st century? What are we really talking about? And I can just be very candid with you. It means to have a certain kind of temperament, to make certain kinds of political and ethical choices, and to exercise certain analytical focuses in targeting on the catastrophic and the monstrous, the scandalous, the traumatic, that are often hidden and concealed in the deodorized and manicured discourses of the mainstream. That’s what it means to be a leftist. So let’s just be clear about it.

So that if you are concerned about structural violence, if you’re concerned about exploitation at the workplace, if you’re concerned about institutionalized contempt against gay brothers and lesbian sisters, if you’re concerned about organized hatred against peoples of color, if you’re concerned about a subordination of women, that’s not cheap PC chitchat; that is a calling that you’re willing to fight against and try to understand the sources of that social misery at the structural and institutional level and at the existential and the personal level. That’s what it means, in part, to be a leftist.

That’s why we choose to be certain kinds of human beings. That’s why it’s a calling, not a career. It’s a vocation, not a profession. That’s why you see these veterans still here year after year after year, because they are convinced they don’t want to live in a world and they don’t want to be human in such a way that they don’t exercise their intellectual and political and social and cultural resources in some way to leave the world just a little better than it was when they entered. That’s, in part, what it means to be a leftist.

Now, what does that mean for me? It means for me in the United States — and I go back now the 400 years to Jamestown. You all know this is the 400th anniversary of the first enduring English settlement in the new world. It was Roanoke before, but it didn’t last. Jamestown last, right? And what do you have at Jamestown? The Virginia Club of London, an extension of the British Empire, makes its way over, the three boats whose names we need not go into at the moment. And what did they do? They interact with another empire, the Powhatan Empire, that’s already in place, of indigenous peoples. You actually get the clash of empire. This is the age of empire.

But what are they here for? Looking for gold and silver and, secondarily, to civilize the natives. So already you get America as a corporation, before it’s a country. Corporate greed is already sitting at the center in terms of what is pushing it. And corporate greed, as Marx understood it, capital as a social relation, an asymmetrical relation of power, with bosses and workers, with those at the top who will be able to live lives of luxury and those whose labor will be both indispensable, necessary, but also exploited in order to produce that wealth.

Then there’s religion, to “civilize” the indigenous people. Now, you can’t talk about the U.S. experience — and I think in many ways this is true for the new world experience — without talking about the dominant role of religion as an ideology. And we also know one of the reasons why vast numbers of our fellow citizens today in the United States, one of the reasons why they’re not leftists, is precisely because they have not been awakened from their sleepwalking. They have not been convinced that they ought to choose to live a life the way we have chosen, in part because we’ve been cast with the mark of the anti-religious or the naively secular, or what have you.

And that’s 98 percent of fellow citizens. So no matter what kind of political organization Brother Stanley is talking about, he’s going to get Gramscian about it. He’s got to dip into the popular culture of the everyday people, and 98 percent them are talking about God. That’s 97.5 percent of fellow Americans believe in God. Seventy-five percent believe Jesus Christ is the son of God. Sixty-two percent believe they speak on intimate terms with God at least twice a day. That’s who we’re dealing with in terms of our fellow citizens. You can’t talk about organization that’s sustained over time, unless you’re talking in Gramscian terms of how do you tease out leftist sentiment, vision, analysis, in light of the legacy of these dominant ideologies — Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, and so forth and so on.

But then, what else happens? 1619, you’ve got white slaves and you’ve got black slaves. You have the first representative assembly that takes place as modeled on the corporation, but it is attempt at democratic elections, the first representative assembly. They gathered July 30, 1619. They cancelled August 4, because it got too hot. And 13 days later, here comes the boat with the first Africans. And at that time, slavery was not racialized. You had white slaves and you had black slaves.

But the white slaves, you look on the register, 1621, they had names like James Stewart and Charles McGregor. But you look on the right side and you see Negro, Negro, Negro, Negro. So even before slavery became a perpetual and inheritable structure of domination that would exploit the labor of Africans and devalue their sense of who they were and view their bodies as an abomination, you already had the black problematic of namelessness. White supremacy was already setting in as another dominant ideology to ensure that these working people do not come together.

And corporate greed would run amok in the midst of that kind of deep and profound division, which is not just a political division. It’s a creation of different worlds, so that the de facto white supremacist segregation that would be part and parcel of the formation of the American Empire would constitute very different worlds and constitute a major challenge to what it means to be a leftist in America from 1776 up until 1963, given the overthrow of American apartheid, which took place in the ’60s. And then, we now wrestle with the legacy, with the triumph of the black freedom movement and all of the white and black — I mean, the white and brown and yellow and Asian comrades who were part and parcel of that black freedom movement that broke the back of American apartheid in the ’60s.

What am I saying? I’m saying, in part, that at least for me to be a leftist these days, in the way in which — and I take very seriously Antonio Gramsci’s concern about the historical specificity of the emergeous sustenance and development and subsequent define of the American Empire. And when you actually look closely at that empire, it seems to me what we have to come to terms with is the fundamental role of corporate greed, religious ideologies, white supremacy, the fundamental role of the popular culture, youth, and acknowledge that anytime you’re talking about white supremacy, you’re always already in some ways talking about the treatment of black women. And if you’re concerned about the treatment of black women, you ought to be concerned about the treatment of women across the board. So the vicious ideologies, the patriarchy, come in. And the same thing would be true for the James Baldwins and the Audre Lordes, the gay brothers and the lesbian sisters.

Now, where does that leave us? Well, for me — and you all know about the Covenant movement of Tavis Smiley, the book that was launched last year, went number one in The New York Times. We sold 400,000 copies within nine months, not reviewed by The New York Times, not touched by the Today Show. Even Oprah wouldn’t breathe on it. And she can breathe on books and sell half a million these days, you know that? We just ask Sidney Poitier and Brother Elie Wiesel for that. But this book went underground.

Why? Because Tavis Smiley knows that in an American culture that is so thoroughly commodified, driven by corporate greed, thoroughly commercialized, driven by corporate greed, thoroughly marketized, driven by corporate greed, you have to be able to communicate in such a way that you might be able then to shake people from their sleepwalking, which he’s done every year now on C-SPAN, and uses his position in order to raise issues of right to healthcare, community-based policing so you can deal with some of this police brutality, especially in black and brown communities of proletarian and lumpenproletarian character, and so forth.

You look in The New York Times last Sunday: volume two was number seven, 150,000 copies sold in three weeks. Three weeks. We just got off a 21-city tour. We did a 22-city tour last year. The book, not reviewed at all. Mainstream television won’t touch it.

What is going on? Is the Ice Age beginning to melt? Is it the case that the 35 years that Brother Stanley talked about, the Ice Age, the historical period where it’s fashionable to be indifferent to other people’s suffering — indifference is the very trait that makes the very angels weep, to be callus toward catastrophe. And it’s true, New Orleans was catastrophic before Katrina hit. Flint, New Orleans without Katrina. We can look at places in Brooklyn, Harlem, South Side of Chicago, barrios in East Los Angeles, white brothers and sisters in Kentucky, Appalachia, wrestling with catastrophic situations. Catastrophic situations.

Meaning what? Meaning that maybe we’re at a moment now where there’s going to be multiple strategies going on. It’s clear that the Democratic Party remains clueless, visionless and spineless for the most part. Does that mean you give up on them? No, doesn’t mean you give up on them, but you have to be honest with them. But it does allow one to, in some way — and this is what I think Brother Rick Wolff was talking about in terms of the desegregation of the right-wing consensus, the unbelievable ways in which now right-wing fellow citizens are at each other’s throats. The evangelical right wing can’t stand the free marketeers, can’t stand the balanced-budgeters. That’s fine. Let them fight. Let them fight. Let them go at each other. They’re weakened in that way.

But what kind of alternative do have we? I don’t have an answer to that. I don’t think that the left has enough resources, has enough people to constitute a strong political organization, Stanley. We can argue over that. We just had drinks for two hours, so we’ve already had some discussion. I think that by raising the issue, it forces us to come to terms with who we really are. That’s what I like. That’s Socratic. That’s provocative.

Now, what we do with it, I don’t know. I really don’t. And the reason why I say that is because historically for me, you know, most of the kind of leftist movements tended to actually respond to reformist activity in which the struggle against white supremacy was a major catalyst. And so, when I think of all the work that I’m doing right now, especially in black America, but always, of course, tied to an instant coalition, leftist identity is not going to be the major means by which you get at people to wake up and come to terms with their social misery, be willing to stand up courageously, articulate vision, and most importantly, have a slice of people who are willing to live and die for a cause, you see, because they have other stories and other narratives that they use to do that.

So I would even argue, in some way, that Martin King and Fannie Lou Hamer were much more important than the Black Panther Party. They were actually building on what Martin and the others built, as much as I love Huey and Bobby Seale. They took it further. But the door was opened by these reformist activities. And what I would love to see is the radical reformism once more become fashionable among young people, and then allow the leftists to come in and do our thing. That’s what I’m looking for. I’d better stop now. Thank you for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: Princeton University Professor Cornel West speaking at the Left Forum here in New York City.

Media Options