Related

Guests

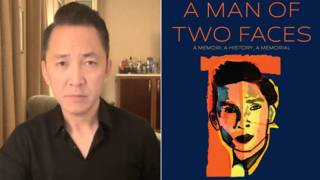

- Don CheadleAcademy Award-nominated actor. He is co-author of Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond.

- John Prendergastsenior adviser to the International Crisis Group and one of the leaders of the ENOUGH campaign. He is co-author of Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond.

We speak with Academy Award-nominated actor Don Cheadle and renowned human rights activist John Prendergast about their new book, “Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond.” On visiting Darfur, Cheadle says, “Once I had seen it with my own eyes and understood and listened to the people’s stories, it was very hard to just return to my comfortable life and not do anything when I had the opportunity to do a lot more.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: For the first time, the International Criminal Court has issued arrest warrants for crimes allegedly committed in the conflict in Darfur. Sudanese Humanitarian Affairs Minister Ahmad Muhammad Harun and a Janjaweed militia leader known as Ali Kushayb are accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes. The charges center around their alleged roles in joint attacks in West Darfur that killed hundreds of civilians. The Sudanese government says it has no intention of handing over the accused pair.

More than 200,000 people have been killed and two-and-a-half million displaced in fighting between rebels and government-backed militias since early 2003. A 7,000-strong African Union contingent is conducting a peacekeeping mission in the region with logistic support from NATO. This past weekend, protests were held around the world to call for more international action to end the mass killings in Darfur.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined now by two leading voices in the Save Darfur movement: Don Cheadle is the Academy Award-nominated actor, whose films include Hotel Rwanda, Traffic, Crash and Reign Over Me. John Prendergast is a senior adviser to the International Crisis Group, one of the leaders of the ENOUGH campaign. He worked at the White House and State Department during the Clinton administration. He travels regularly to Africa’s war zones. John Prendergast and Don Cheadle have just co-authored a new book. It’s called Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond.

I want to begin with John Prendergast and ask you — you worked under the Clinton administration. The Clinton administration refused to call what was happening in Rwanda a genocide until it was too late, though you weren’t there at the time. The Bush administration has called what’s happening in Darfur a genocide, yet what is it doing about it? What’s the difference whether they call it that or not?

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Well, apparently not much. The convention is a vague document — the Genocide Convention — but it does, in fact, have one specific operative phrase, and that is that the signatory states must do all that they can to punish the crime of genocide, and for four years we’ve had no accountability for those that have perpetrated and orchestrated this most heinous crime. So that’s really the bottom line: Is the Bush administration going to impose punitive measures on the government of Sudan or not?

AMY GOODMAN: Don Cheadle, you, of course, received an Academy Award nomination for your portrayal of Paul Rusesabagina, the Rwandan hotel manager who’s credited with saving 1,200 Rwandans from slaughter. He has also joined the movement to call attention to Darfur. He spoke at a rally in Washington, D.C., just over a year ago.

PAUL RUSESABAGINA: More than 12 years ago in Rwanda, a militia was slaughtering innocent civilians on the hills, in the cities and towns. Today, last year I went to Darfur. What I saw in Darfur is exactly what was going on in Rwanda during that time: more than two million people displaced without food, without shelter, without water, without education, which is the basic need for our future generations without any other hope. Ladies and gentlemen, what I saw in Darfur is a disaster and a shame to mankind. The international community, as Rwanda has been abandoned, Darfur is also abandoned.

AMY GOODMAN: Paul Rusesabagina, the Rwandan hotel manager who Don Cheadle played in Hotel Rwanda. As you were making this film, the foundation was being laid for the genocide in Darfur. How did you go from Rwanda to Darfur, Don?

DON CHEADLE: Well, we had a screening of the film at an MGM facility in California, and Congressman Ed Royce from Orange County saw the film, and he and I met, and he told me that he had been trying to draw attention to the conflict in Darfur and believed that the film was a good example of what was happening and depicted the story in a way that he could bring others to understand what was happening and invited me to go with he and several other congresspersons on a congressional delegation to the area to see for myself what was happening. And John Prendergast came along, and we toured the camps, and I was able to get a firsthand accounting of what happened. And once I had seen with my own eyes and understood and listened to these people’s stories, it was very hard to just return to my comfortable life and not do anything when I had the opportunity to do a lot more.

JUAN GONZALEZ: John Prendergast, I’d like to ask you about the International Criminal Court. Clearly the Bush administration has had a very antagonistic view of the criminal court. How now with this new finding will the Bush administration deal with the reality that at the same time it’s been opposing the International Criminal Court on the world stage?

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Well, the United States government, the Bush administration, has a whole lot of potential leverage that it’s squandering by its non-cooperation with the court. We don’t expect the Bush administration to sign the treaty, but we could, in fact, expect the administration to provide some declassified intelligence and information to the court in order to accelerate the indictments of some other senior officials within the regime that are more responsible for orchestrating the genocidal crimes that have been committed in Darfur. That, I think, is the — one of the most pressing policy imperatives today is to have the Bush administration quietly cooperate by providing information to the court to finally impose a cost for committing genocide.

AMY GOODMAN: A while ago, the Los Angeles Times, John, did a major expose that revealed that the U.S. has quietly forged a close intelligence partnership with Sudan, despite the government’s role in the mass killing in Darfur. The Sudanese government has since publicly confirmed it’s working with the Bush administration and the CIA. Can you talk about that relationship that they have in the so-called war on terror and how that relates to the killings in Darfur?

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Well, in the early to mid-1990s, at the invitation of the Sudanese government, Osama bin Laden lived in Sudan, and a number of other terrorists either lived or transversed throughout Sudan on Sudanese passports. Obviously, the ultimate dream of a terrorist organization is to have a state sponsor, because you get all the accoutrements of the state, and al-Qaeda benefited greatly in its incubation period from its residency in Khartoum. And so, although later, after the United States and other countries pressured the Sudanese regime to cut its ties, the regime did retain all of its very, very valuable records about all of the networks, the businesses and the individuals and their aliases operating in many of the terrorist groups that the United States now, along with other partners around the world, is working against.

So I think Sudan has become invaluable as one of the many governments around the world that are cooperating with the United States on terrorism, and clearly the Bush administration prioritizes that over everything else and has been unable to pursue at the same time a policy that maximizes cooperation on the counterterrorism front, whilst trying to bring an end to this genocide.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to John Prendergast and Don Cheadle. We’ll be back with them after this break. We’re talking Darfur.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: I’m Amy Goodman with Juan Gonzalez, as we talk with Don Cheadle, Academy Award-nominated actor who’s films include Hotel Rwanda, among others, and John Prendergast, who is a senior adviser to the International Crisis Group. Both have traveled to Darfur. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: Don Cheadle, I’d like to ask you: Why Darfur? Clearly there have been in Africa many conflicts that have taken huge numbers of lives, certainly the Congo, the civil war in the Congo in recent years, and right here in the United States we’re confronting mass killings occurring on a daily basis in Iraq, that some people would say that the movement for Darfur to highlight the genocide in Darfur is at the same time not dealing with what our own country is doing in Iraq. Why did you feel it so important to raise this issue?

DON CHEADLE: Well, I don’t think — I think people are sensitized to do what they are called to do, and I was with regards to Darfur, maybe because of the similarities of what I just experienced even fictitiously with Hotel Rwanda. But I believe that genocide is the highest crime that humanity has to face. And if we are going to call it by its rightful name, which is the first time we’ve ever had a sitting president do that, then there should be an action that results from that. And if we do not strenuously attempt to interject ourselves into this process and quash this, then I just think it sends a terrible signal to everyone in the world that these crimes can go unpunished and that when something like this occurs, you cannot look to the international world body to intervene. I believe it emboldens people who would want to do it in the future. And it is, again, as I say, it’s the highest crime that I believe humanity can commit, and we want the entire world to stand on notice and attempt to put it down.

AMY GOODMAN: Don Cheadle, describe what it was like to travel to Darfur. What route did you take?

DON CHEADLE: Well, we came in — at first we came through Chad, and then we crossed near an AU — one of the AU missions where the AU is located, and we just went through one of the villages there that had prior to our arrival had 40,000 — 4,000, rather, members there, and it had been burned out. Huts had been abandoned. Things were just left in a state of — you could tell people had just left with whatever they could carry. And it was just shocking and tragic to know that this was basically a ghost town that had been thriving and full of citizens not long before we had arrived.

AMY GOODMAN: John Prendergast, a question about corporate involvement: On May 5, there’s going to be the shareholders’ meeting of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s company. Can you talk about corporations and their involvement in Sudan?

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Well, of course, there’s corporations all over the world who, wherever there’s money, they will go, and in Sudan over the last 10 years we’ve seen a rapidly escalating profit margin in the oil sector there. Sudan has gone from producing nothing but a few small agricultural products to now being a mid-level oil producer, which earns perhaps four or five billion dollars a year in oil revenue — that’s conservative estimates. And so, you’ve got a lot of oil companies, particularly Chinese, Indian and Malaysian, who have invested heavily during this last decade to ensure that this sector becomes as profitable as possible. And then, there are a lot of ancillary companies that have invested.

So, in response to that, American citizens all over this country began a process of what they call divestment, pressing for mutual funds, for university endowments and state and municipal pension funds to sell the stock of companies that are doing business in Sudan and underwriting this genocidal regime. So you have at least now nine states which have passed laws. Governors have signed into law divestment measures. You have a number of universities all over the country that have done the same. And now, as you asked, Berkshire Hathaway, as one of the largest purchasers in the United States of the stock of the Chinese oil company that’s the major investor in Sudan, activists, shareholder activists are targeting Mr. Buffett and asking him to sell, to just dump the stock, the Chinese stock, that’s in his portfolio and just buy some other energy company, if he wants to remain diversified in that fashion.

JUAN GONZALEZ: John Prendergast, in your book you also talk about the situation in Uganda and the Lord’s Resistance Army. Could you talk about the relationship between the two crises?

JOHN PRENDERGAST: I think, on the one hand, the relationship is that — marked by some of the most terrible atrocities that we’ve ever heard about or seen. Both of us traveled to northern Uganda and to Darfur, because we think that in addition to Congo these are two of the worst civil conflicts in the world. And on the other hand, the similarities are that, you know, we’re talking about small groups of people who, given the motive, can do tremendous damage.

And it doesn’t require a massive army. It doesn’t require billions of dollars in either case, in northern Uganda or in Darfur, to get a solution. It simply requires diplomatic leadership by the United States on the peace process in both places to help support some protection of people, whatever that means. In Darfur, it means deploying a U.N.-led force. In Uganda, it means making sure the Ugandan army is not as abusive as it is, and it means deploying human rights monitors and then providing the leverage necessary — again, punishing the perpetrators, using the International Criminal Court and other measures like targeted sanctions and asset freezes — against those that would be willing to commit these kinds of crimes.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And, Don Cheadle, there are some who say that this genocide is racially based, that it is largely a Arab regime attacking a largely black African population. Others claim that this is simplistic, that there are many more class and historical factors involved. Your perspective?

DON CHEADLE: Well, I think all of those are a factor. I do think it is racially based, but we’re not talking about the largest percentage of the Arab population there. These are conscripted soldiers who do have a racist ideology, who have been funded to do what they’re doing with the promises of the spoils of war. And they’re taking advantage of that, obviously, to — the GOS, the government of Sudan, is taking advantage of that to maintain power. So I just want to caution those to say this is Arabs versus Africans. This is the nature of this particular conflict, but again, it’s a very small percentage that we’re talking about that have been armed and have been unleashed on the civilian population.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to talk more about what proposals are on the table to end the killings in Darfur. Last September, we interviewed Alex de Waal, the specialist and a foreign adviser to the African Union. The U.N. Security Council had recently voted to authorize more than 20,000 troops and police officers for Darfur, but the U.N. force was strongly rejected by the Sudanese government. This was what Alex de Waal had to say.

ALEX DE WAAL: What President Bashir of Sudan has done is he’s called the bluff of the U.N. and the U.S. The U.N. and the U.S. have said, “We want to send a force.” And they’ve implied that if the Sudan government doesn’t agree, they will force it on them.

But what is the reality of this? Are we really going to send an army to Darfur to invade against the wishes of the Sudan government, to face the military resistance of the Sudan government and its militias? And the answer, frankly, is no. Are we going to be able to impose sanctions that are tough enough on the Sudan government, which has after all been under sanctions of one form or another for 17 years, that will make them comply? This is a country that is an oil exporter that has good relations with all its neighbors now, has good relations with China and Russia. The answer, frankly, again is no.

So, let’s recognize that posturing and wielding a bigger stick, frankly, is not going to work. The bluff of that has been called. Let’s get back to a discussion. Let’s get back to negotiating a political solution that starts with a ceasefire, that starts with saying we can solve this problem, but we can solve this problem only with the consent of all. And the first step is the fighting must stop. And I personally am confident that this is the only way. It may be a long shot. Time is very short. We’re really very, very close to some deadlines, and if we pass those deadlines, if we pass the end of this month and the African Union forces withdraw, then we’re in a very, very dismal situation. But we do need to rescue this politically.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Harvard Professor Alex de Waal. John Prendergast, your response?

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Yeah, well, I think Alex is famous for setting up straw men and knocking them down. Nobody is talking about invading Sudan. What we’re talking about is pressuring the government more robustly in order to accept a United Nations-led force to protect people while a peace agreement is negotiated.

And I think that how you get there is doing — Alex and I simply disagree — is by imposing the kinds of measures that affect the Sudanese government’s wallet and affect their calculations through the possibility that they will be prosecuted for war crimes for the rest of their lives. And so, I think with this kind of leverage — we have seen three times in the last 18 years in the life of this government, when real sanctions have been imposed or military threats have been preferred by the international community or the regional states, that Khartoum has actually changed its policies. So we have empirical evidence that when you pressure this government with real tools, with punitive measures, that they actually respond.

But we haven’t done that yet, because of the counterterrorism connection that you talked about earlier. If we decide to move forward with these specific measures, we’re going to see this government change its policies, allow the U.N. force to come in and stop the genocide, and it’s time to undertake those measures now.

JUAN GONZALEZ: But, John Prendergast, what about the situation with the — you talk about the Khartoum government — but the rebels themselves? Previous reports by a U.N.-sponsored investigation have alleged war crimes being committed by the rebels themselves, that it’s not simply just a question of the government’s attack on the civilian population.

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Sure. I mean, the preponderance of attacks, preponderance of crimes against humanity have been committed by government forces or government-supported Janjaweed militias. The rebels are also responsible for some terrible attacks, and I think they should equally vigorously be prosecuted by the International Criminal Court for any actions of this nature, and we ought to impose sanctions on any of the rebel leaders who are either committing atrocities or are undermining the peace process.

AMY GOODMAN: Paint a picture for us, John Prendergast. You have been in Darfur many times. How does the violence take place? Describe a village for us, someone that you have spoken to.

JOHN PRENDERGAST: Sure. Well, the pattern is almost eerily similar every time. You know, the story normally starts at 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning, when the Antonov bombers, the high-altitude aircraft Russian-made bombers — Russian-sold bombers, as well — initially buzz across above a town two or three times, then they drop their payload and bomb the town from above. This destabilizes the town. People are running everywhere, and the Janjaweed militias storm in on horses and camel, and they kill and loot and rape with total impunity, and they’re usually backed up by a government force on the outskirts of the village, sometimes small, sometimes large, depending on how large the village is.

Now, this has happened 1,500 times, according to the satellite imagery that’s been collected, which any viewer can go onto Google Earth and view just by typing in Darfur — that about 1,500 villages have either been completely or partially been burned to the ground in this kind of an attack.

So the survivors, the people who escape, then end up in these camps of thousands of people, whether internally displaced camps inside Darfur or in refugee camps across the border in Chad. And they are then highly vulnerable to the government of Sudan usually, and sometimes the rebels, turning on and off the aid tap. So there’s about a million people now in Darfur who are beyond any reach of the humanitarian aid agencies. So we just don’t know what’s going on in these areas. We simply don’t know whether people are dying en masse. And it is an absolute critical emergency to undertake the kind of policies necessary to deal with this, or we could see the cataclysm of Darfur get even worse.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And, Don Cheadle, I’d like to ask you — obviously you have taken a very high-profile position on this, so have several other Hollywood stars, like George Clooney, as well — what has been the impact in terms of being able to mobilize public opinion here in the United States, and is this having an effect on the public in other countries?

DON CHEADLE: Well, I believe that I’ve seen, since I became involved years ago, much more awareness. I know that at the beginning, when I would just mention the word “Darfur” to people, people wouldn’t know what I was talking about, and I’ve seen a big change in that. And I can’t speak for George or the other celebrities, but I know that I wanted to take the attention that’s often given to me for whatever role I’m portraying and whatever job I happen to be doing and just try to refract that and reflect that and point to something that I think is a grave cause and that we need to all pay attention to. And, you know, the proof will be in the pudding. We will see what this movement will do.

We believe we’re at a watershed moment in several ways. We have the 2008 Olympics coming up in Beijing, and we want to highlight China’s connection to this problem and really have the public awareness about that and ask what China is doing. We want to inject this into the debate. We have an election coming up in this country, obviously, and six of the candidates, at least six of them, have either traveled to the region or written extensively about it, and we want to inject this question into the debate: What will be done? What is your policy toward this? And we have this Plan B, which is sitting, if not on the desk now, in the wings for our president to sign, which we believe will give some real teeth to this process and hopefully see a result. The EU has come out and said that by June if nothing has been done, there will be something done. I mean, we haven’t been at this moment in time until now, where all of these things sit at the precipice, hopefully, and we can push these things over and get some results.

AMY GOODMAN: Don Cheadle, you mentioned the presidential candidates. Your book has an introduction by Senator Sam Brownback and Senator Barack Obama. Barack Obama has been speaking out on Darfur. Would you say he has taken, of all the presidential candidates, the most aggressive stance on it? And what is it?

DON CHEADLE: Well, Senator McCain has likewise spoken about this very strongly, as has Senator Clinton, and I believe they are all saying — the rhetoric is all the same — that this must be stopped. What we want to know is what, beyond the rhetoric, are we prepared to do. What will we be willing to do?

I met lately with Secretary Rice, and she spoke to me about when they were trying to solve this Lebanon-Israel issue in the last year, that she sent a special — not an envoy necessarily, but she sent someone from her department to sit on the bureaucracy in the United Nations and push this through and make sure that this red tape was cut through and that there was a solution. And we believe that the situation in Darfur should at least get that same sort of consideration and that it should be raised to that level of importance.

So we want to know what these candidates are willing to do and what they will go on record to say, and if they don’t say it, that we hold their feet to the fire and press them on this issue. It’s of grave importance to us.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And, Don, could you talk about the role of young people here in the United States, college students and others who have become involved in this issue, and their impact on the debate?

DON CHEADLE: Well, one of the most rewarding things that I was able to witness up close and we discuss in our book: Adam Sterling with the Darfur Action Committee — who used to be before he graduated from college, graduated from UCLA — got together with several of his fellow students and asked themselves the question of what could they do, and they were the leaders in the divestment movement at that school, not only in that school, but the entire UC schools, and they were able to push through divestment measures. And that rolled into, with Paul Koretz becoming involved, that happening at a state level. And he is now working with the Sudan Divestment Task Force to see that that happens all across the country. And we’re seeing real results, and this is coming from the youth movement. So I’ve been very heartened by what young people in this country are doing and have done and would encourage them to stay a part of the process. And I do believe we’ll see results.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you both for being with us, Don Cheadle, actor whose films include Hotel Rwanda, Traffic, Crash, Reign Over Me. He, together with John Prendergast, senior adviser to the International Crisis Group, one of the leaders of the ENOUGH campaign, have co-authored the book, Not on Our Watch: The Mission to End Genocide in Darfur and Beyond, Including Six Ways You Can Help Today.

Media Options