Related

Guests

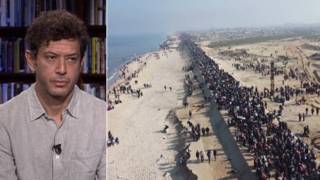

- Tom SegevIsraeli historian and a columnist for the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz. He is author of the new book 1967: Israel, The War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East.

- Dr. Mona El-Farradirector of Gaza Projects for the Middle East Children’s Alliance and writes the blog “From Gaza, with Love.” She has just begun her first U.S. speaking tour.

- Norman Finkelsteinassistant professor of political science at DePaul University. His latest book is Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History.

Israeli historian Tom Segev, Palestinian physician Mona El-Farra and U.S. scholar Norman Finkelstein discuss the circumstances around the 1967 Six-Day War and its consequences in the ensuing 40 years.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: As we continue our discussion of Israel and the Occupied Territories, we turn to the words of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. Earlier this week, he discussed the impact of the 1967 war on the Palestinians.

PRESIDENT MAHMOUD ABBAS: [translated] Even in June, the Six-Day War went down in history as marking the defeat of the Arabs by Israel. Our standing up to this defeat, in spite of the hardships, could make up for what we have lost in war. Perhaps we can even erase it from memory with a great achievement, putting an end to the occupation of Palestinian and Arab lands, creating our independent state, recovering our Jerusalem, solving the refugee problem in a just and acceptable manner based on legitimate international resolutions.

AMY GOODMAN: On Wednesday, Israel’s deputy premier, Shimon Peres, claimed Israel did not intend to occupy the West Bank and Gaza in 1967.

SHIMON PERES: The Six Day War wasn’t a war that we were seeking. We were forced into it. We didn’t intend to conquer any territories. This was a result of a forced war upon us. On many occasions we tried to negotiate and settle the burning issues. And I didn’t lose my hope. We wouldn’t like to see the Palestinians suffering. We wouldn’t like seeing the Palestinians occupied. We wouldn’t like the Palestinians missing a chance of a flourishing and democratic economy. We are ready to negotiate, straightaway, fully, sincerely and responsibly.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about the Six-Day War of 1967, we’re joined by three guests. Tom Segev is an Israeli historian and columnist for the Israeli newspaper, Ha’aretz. He’s the author of the new book 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East. The Palestinian doctor and human rights activist Mona El-Farra also joins us here in New York, director of the Gaza Projects for Middle East Children’s Alliance, writes the blog “From Gaza, with Love.” She’s just begun her first U.S. speaking tour. And Norman Finkelstein joins us in Chicago, where he’s a professor of political science at DePaul University. His latest book is Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History.

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! Tom Segev, I’d like to begin with you. Go back 40 years. Tell us what happened this week 40 years ago.

TOM SEGEV: It all began when Palestinian terrorists started to penetrate Israel through Syria, which caused tension along the Syrian border. That then spread to tension along the Egyptian border. Egypt made threats and threatening moves, and Israelis genuinely believed that they are facing a second Holocaust. There were very, very weak. The society was very weak. And so I think that war with Egypt, at that time, was inevitable for this reason, because Israelis were too weak not to strike at Egypt. But that was only one of the three weeks fought that week. There was also a war with Jordan and also a war with Syria.

And I think that taking the West Bank and East Jerusalem contradicted Israel’s national interest. And it is not something I’m saying in hindsight. This is something Israeli policymakers knew at the time, six months prior to the war. They had actually concluded that it will not be in Israel’s interest to take to West Bank. Comes the day, June 5th, 1967. Jordan attacks West Jerusalem. All reason is forgotten, and they take East Jerusalem and the West Bank, in contrast to Israel’s national interest, as defined by them six months previously. So it’s a completely irrational thing. It’s about religion. It’s about emotion. It’s about 2,000 years of longing for Zion. It’s not about strategy. It’s not about national interest.

AMY GOODMAN: The role of the United States and Britain at the time?

TOM SEGEV: Britain was not that important. United States tried to prevent the war. President Johnson, actually, was against military action. He, through the rest of his life, thought that the Six-Day War was a mistake. And Israel eventually did not go to war until we received a green light from the United States, a reluctant green light. The major problem for Johnson was the fear that the war wouldn’t go so well, and Israel would turn to the United States and ask for military assistance, and that would get them involved, in addition to the war in Vietnam already. But he was convinced that Israel can do it alone.

AMY GOODMAN: Abba Eban went to Washington—

TOM SEGEV: Yes, Abba Eban went to Washington.

AMY GOODMAN: —to plead with Johnson?

TOM SEGEV: That’s right. That’s right. And he had two meetings with him, and—but that was not when he got the green light, actually. Johnson asked for a postponement, and Israel agreed to postpone the war. It was only later, when the head of the Israeli Mossad, Meir Amit, went and had talks with the CIA, when the green light was actually given.

AMY GOODMAN: Norman Finkelstein, you, too, have written extensively about what happened in 1967. Can you describe events as you researched them? We will continue with Tom Segev, and we’ll link Norman Finkelstein up in just one minute. So, then the war began. Explain what happened in those days.

TOM SEGEV: The war with Egypt was won within hours, really. Israel destroyed the Egyptian air force. And that was actually part of what led the Israeli government to decide to take the West Bank, because from a very, very great fear, they had moved very, very rapidly to great euphoria. And it was that euphoria that actually contributed to the decision to take the West Bank. East Jerusalem was taken. The West Bank was taken. And eventually the Golan was also taken. So, by the end of the war, Israel controlled vast amounts of Arab land and a very large Palestinian population. The problem at the beginning was that the Palestinians did not resist. They came to work in Israel. The Israelis went to the West Bank. Everything seemed as if it’s possible, and no one tried to force Israel to give these territories back. And, of course, once taken, East Jerusalem could not be given back because of political reasons and because of religious reasons. So it was a very harmful decision to take it in the first place, and the West Bank also.

AMY GOODMAN: Mona El-Farra, you’re a physician in Gaza. Can you talk about what happened in Gaza for you, how you experienced 40 years ago? You were born in Gaza?

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: Yeah, I was born in Khan Younis in the south of Gaza Strip.

AMY GOODMAN: In Khan Younis.

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: And during the war, I was only 13 years old, and it was sort of a shock for me. We stayed in the basement for about five or six days. And after that, after the war have ended and I realized that the Israeli—now I am face to face with the Israeli army, with the Israeli people—I did not see any Israeli before, so it was sort of shock for me. And all my life have changed because of the occupation. As a teenager, as youth later on, I was in the demonstrations protesting against occupation, so I am surprised about what Tom just have said. The resistance to occupation started the first few months of the occupation. For me, I experienced it as a teenager in the school, school student, actually.

AMY GOODMAN: You were about, what, 13 at the time?

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: Thirteen, yes, 13. But just a few months later, it was sort of organizing demonstrations against the occupation. And I was part of this. And I considered this sort of resistance.

TOM SEGEV: That’s right. That’s right.

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: So the resistance to occupation is there from the first few minutes, despite of the fact that labor started to go to Israel, but it was sort of cheap labor. And people wanted to continue with their life. It was sort of overwhelming incident for me, for all my upbringing and for all years of my future years, because at that time I decided to go to medical school because of what I have seen during the war, the wounded people and the hospitals and how the lack of medical facilities were there during the war. So, I say again, resistance to occupation started the first few months of the occupation.

AMY GOODMAN: Tom Segev?

TOM SEGEV: That’s, of course, true. There were also leaflets, also strikes in Jerusalem, teacher strikes, lawyer strikes. That’s, of course, right. But it wasn’t strong enough, and it led to the Israeli illusion that everything is temporary and that we have all the time in the world, and all we need do is to wait. And that is what I mean, because we all remember the hijackings of the plane and other very spectacular terrorist acts by the Palestinians in the 1970s. So, a few months is already a long time, because after a few months, until then, this illusion was already born that there is such a thing as—you know, the Israel term was “benevolent occupation,” some Israeli invention, as if we can control you, and you will take it. And that lasted for a few years. And I think that by looking back today, A, we are stuck in that illusion that everything can work, that everything is temporary, and B, I think, looking back, Israel gained absolutely nothing from taking the Palestinian territories.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to Professor Norman Finkelstein now in Chicago at DePaul University. Your take on Israel’s reasons for going to war in 1967?

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: Well, there are two aspects to the Israel-Palestine/Israel-Arab conflict. There’s the relationship to the Arab world in general, and there’s the relationship to the Palestinians. June 1967 was not really about the Palestinians; it was about Israel’s relationship to the Arab world generally. The main purpose of the June ’67 war—and Tom Segev is quite clear about in his book—was, depending on who you quote, to crush Nasser, to deal a knock-out blow to Nasser, and to defeat Nasser. The Israelis, in particular, Ben-Gurion—

AMY GOODMAN: Of course, Nasser being the president—

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: —feared that in the Arab world there would emerge a leader—

AMY GOODMAN: Norman, Nasser being the president of Egypt.

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: Excuse me?

AMY GOODMAN: Nasser being the president of Egypt.

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: Yes. The Israelis, in particular, David Ben-Gurion, the first prime minister, feared, from early on, that an equivalent to Ataturk in Turkey would emerge in the Arab world—namely, a secular nationalist leader who would modernize the Arab world. And so, from early on, the Israelis were dead set on defeating Nasser and dealing a blow to him. Already by 1954, the Israelis were trying desperately to provoke a war with Nasser. Unfortunately for the Israelis, Nasser didn’t take the bait, and in 1956 they launched an invasion with the British and the French. Now, come 1967, through a concatenation of events, a new opportunity arose to knock out Nasser, and that was the chief aim in '67. A ancillary aim was to conquer various parts of various areas bordering Israel—namely, the West Bank, the Sinai and the Golan—but that wasn't the primary goal. The primary goal was to deal a deathblow to Arab nationalism, to pan-Arabism.

AMY GOODMAN: Tom Segev, would you share that analysis?

TOM SEGEV: I don’t know what book Mr. Finkelstein has read. He has not read mine. That is not what it says in my book.

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: I read your book several times.

TOM SEGEV: I distinguish between three books—three wars, war between Egypt, between Jordan and between Syria, and these are three different stories. The war with Egypt broke out primarily out of weakness, Israeli weakness, Israeli fear of a second Holocaust. One of the things I did for this book was to go to people who live in this country, and I told them, “Go down the basement and up the attic, and look for letters which you received from Israelis in 1966, 1967.” I was able to collect about 500 such letters. These are not letters written to The New York Times or anything. These are letters written from a man to his wife, from a woman to her daughter. And they reflect a genuine Holocaust fear. So, it was weakness which led—no conspiracy, no geopolitical plan to crush Nasser or anything like that. It was just fear that led to the war with Egypt. And therefore, the war with Egypt was inevitable. That is not the case, as I said, with Jordan and with Syria. So talking about the Six Day War is really a misleading term. These are three different wars that were fought that week.

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: May I reply to that?

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Norman Finkelstein.

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: When you’re looking at a conflict of this sort, as in any other country, you have to look at it at two levels, the level of what people, the population, thinks and fears, and then you have to look at the leadership. Now, there’s no question, as Tom Segev accurately states, that the Israeli people, and American Jews, as well, feared a catastrophe in June 1967. But there is equally no question—and I read Mr. Segev’s book very carefully—there is no question that the Israeli generals, as well as U.S. intelligence agencies, were fully confident that Israel would knock out Nasser quickly in the event of a war, as well as they were fully apprised that Nasser had no intention of attacking.

Now, let’s look at the record. As Segev clearly points out in his book, beginning the second week in May, many Israeli officials came to the United States saying exactly what Segev said, that we’re on the verge of a second Holocaust, that the Egyptians are going to attack. And on multiple occasions, U.S. intelligence agencies checked all the information, using Israeli assumptions, and came to two conclusions: Number one, there was no chance that Nasser would attack; and number two, if he did attack, to quote Lyndon Johnson at the end of May, “You will whip the hell of out them.” Now, June 1st, Israel’s Major General Amit, the head of the Mossad, comes to the White House. He’s also trying to feel out the Americans. And he states explicitly, “We agree with all of your data and all of your projections.” There was no fear whatsoever at the level of the Israeli leadership and the Israeli generals that Israel faced a second Holocaust in June 1967. That’s mythology, and I think Tom Segev’s book, unlike what he’s saying now, punctures that mythology.

AMY GOODMAN: Tom Segev?

TOM SEGEV: I’m always amazed by people who seem to know what the Egyptians really wanted, be it on the extreme left, as Mr. Finkelstien, or the extreme right, as Michael Oren. We don’t really know what the Egyptians wanted, because we don’t have Egyptian documents. And it’s also not so important what the Egyptians really wanted; the important thing is what the Israelis thought the Egyptians wanted. The army, the Israeli army, Israeli generals, are coming out of my book as very hysteric people. They thought that if we don’t strike now, we may lose the war. And so they put very, very heavy pressure on the government. It is in fact the civilian government that says to the generals, we need to wait, we need to do everything we can to avoid the war. So, I think the picture is much more composed, you know, complicated than just to say that the Israelis did this or that.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, and then we’re going to come back to this discussion. We’re talking to Tom Segev, Israeli historian and journalist. His latest book is called 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East. Dr. Mona El-Farra is with us, Palestinian physician and human rights activist, living in Gaza, born in Gaza, does the blog, “From Gaza, with Love.” And Professor Norman Finkelstein of DePaul University, his book is Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History. We’ll come back to this discussion in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We continue our discussion on this 40th and anniversary of the Arab-Israel war that took place this time this week, 40 years ago. Our guest Tom Segev, historian and columnist with the Israeli newspaper, Ha’aretz, his latest book, 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East. Dr. Mona El-Farra, born in Gaza, lives in Gaza, writes from Gaza the blog, “From Gaza, with Love.” And Professor Norman Finkelstein, author of a number of books, professor of political science at DePaul University, joining us from Chicago, his latest, Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History.

Tom Segev, you wrote a column in The New York Times on Tuesday, “What If Israel Had Turned Back?”

TOM SEGEV: An op-ed, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: An op-ed piece.

TOM SEGEV: Right, right.

AMY GOODMAN: Now we see—don’t know if it appeared in the Times, but it’s appearing on their website, the Anti-Defamation League saying, “To the Editor, Tom Segev’s look back at the Six-Day War misses a larger point. Israel not only had no intention at the outset of conquering land; afterwards it offered the Arabs return of the land in exchange for peace.

“In both the 1948 and 1956 wars, Israel won land (in the Sinai) but was forced by international pressure to relinquish it without getting any peace or guarantee of quiet in return. As a result, new wars occurred, first in 1956, then in 1967. This time around Israel was determined to hold on as leverage for peace. Israel’s attitude resulted in UN Security Council Resolution 242, peace with Egypt and peace with Jordan.

“How was Israel to know that even the offer of returning land—as at Camp David and the unilateral withdrawal from Gaza—would not only not yield peace but would lead to further Palestinian extremism?

“The history is tragic not because of Israel’s victory in 1967 but because of Palestinian unwillingness to make critical decisions for peace and compromise.”

That’s a letter written by the Anti-Defamation League. Your response?

TOM SEGEV: You’re giving me a hard time, really. You just made me defend myself against the extreme left; now I have to defend myself against the Anti-Defamation League. I really think that, looking back 40 years, we gained absolutely nothing from taking the Palestinian territories—only misery for Palestinians and for Israelis. And I think that we shouldn’t have done it. And now the question is, of course: Could the decision makers in 1967 know how harmful it was to take East Jerusalem and the West Bank? One of the amazing thing about the records from the Cabinet meeting, which I have in the book, is that they never, ever call in experts, not even legal experts, to brief them on the implications of what they are doing. Rationally, strategically, they know that it’s not in the interest of Israel to take these territories, and they still do. So it’s really a moment where we do something which is wrong, and then that lasts for many, many years. Now, the Palestinians have made many, many mistakes. I think that they are still making a mistake today by shooting at this tiny little town called Sderot. I think it’s very bad for them. Terrorism has proved to be very bad for the Palestinians. Oppression has to be—have proved to be very, very bad for the Palestinians and the Israelis.

AMY GOODMAN: Would you call the Israeli state, what it is engaged in, terrorism, as well?

TOM SEGEV: No, I don’t—

AMY GOODMAN: When it kills Palestinian civilians?

TOM SEGEV: Well, some of it, maybe. We really—let’s not generalize. Ask me about a specific case, and I will tell you. Yes, that’s the definition of terrorism, is that does usually not imply to states, but this is playing with words. I think that Israel made many, many wrong steps in the territories. And I think that today it’s really about managing the conflict rather than looking for solutions to the conflict. And I think that there are many things to be done to make life more livable. And Mona, coming from Gaza, she will be the first to agree that it needs to be done to make life more livable.

AMY GOODMAN: Mona, over these 40 years, describe what it is like to live now in Gaza?

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: Yeah, but first I would like to comment on terrorism. I consider Israeli acts in Gaza and in the West Bank state terrorism. State terrorism, I consider it. And I don’t agree with hitting Sderot with rockets, despite the fact that I agree with the right of Palestinian people to resist.

TOM SEGEV: Right.

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: Yeah, but I am against hitting any rockets against civilians, and this implies for both sides, the Israeli and Palestinian side. But what Israel is doing in the Gaza Strip is well defined, known state terrorism. I’m coming from Gaza. The borders are closed. The economical situation is so much deteriorating. Human rights are violated every day, and continuous violation of human rights. And right to health is violated. Right to education, children—children’s right to live peacefully is violated. And when I talk about children, I always think of Palestinian and Israeli children. So, more aggression, more acts against Palestinian in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank will not bring peace or security for the Israeli children.

What will bring peace and security is justice. And when we are talking about justice, justice doesn’t mean to end the occupation now, 40 years of occupation. These 40 years of occupation has been preceded by another 59 years of al-Nakba, when Israel was founded on the ruins of Palestinian people. And it is just the right time to let the world know that Israel should take a small responsibility regarding the refugees, the refugees that have been forced to leave Palestine, historical Palestine, Israel now, those refugees in a big, large ethnic-cleansing operation that happened in 1948. And when you are talking about 40 years of the war, the occupation or the Nakba, we should not forget other Palestinians who are living outside Palestine. So, if we are looking for strategic solutions for future solutions for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, we should think of the whole picture as such, and this piece of land should be—must be shared between both. Maybe it is not right now to say this thing, but this is the future, the future for all to live in peace. And this is my opinion.

AMY GOODMAN: The conflict between Hamas and Fatah, how is that affecting this arrival at some kind of solution?

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: It affected all our lives in Gaza. But to start with, before talking about the conflict, what made this conflict? What are the underlying causes? When Israel left Gaza almost two years ago now, it convinced the whole world that the occupation is over in Gaza. The occupation has never been over in Gaza. Gaza was left—the settlers were forced to leave Gaza under disengagement plan, but Israel still controls Gaza. They can—they control the sea, the land, the borders. They can come and go anytime they want, so—and Gaza was left with 1.4 million population living in this very small piece of land, in very dire general situation, economical, health, all situations are very deteriorating and dire. And so, things are boiling inside Gaza, a lot of arms in Gaza, a lot of factions. And this is the start of the problem. To leave people in big pressure cooker, big prison called Gaza, clashes were inevitable. It should happen. But despite of this, I don’t give any excuses for Fatah or Hamas to go through this inter-clashes. It affected our lives very much in Gaza. I blame both parties. And it made the situation more complicated. And from my point of view, I look at the humanitarian side. It made our lives difficult in Gaza, these inter-clashes.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Norman Finkelstein, the role of the United States right now and the role this government plays in Israel and Palestine?

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN: Well, the role is critical, and it comes out, I think, quite clearly in Tom Segev’s book. The Israelis have always feared what the reaction of the United States would be in the event that they take any initiatives. In 1956, when Israel invaded the Sinai, it was the United States that forced them back. And in June 1967, the main fear of the Israeli leadership, as well as those who were out of leadership, like Ben-Gurion—so, Ben-Gorion, the prime minister Levi Eshkol and others—the main fear was not the Arabs, not defeating Nasser—that was a done deal in their minds. The fear was the United States. Would the United States force them to leave unconditionally as it forced them to leave in 1956? That’s what was holding up the war. The Israelis wanted already—the generals wanted already to attack on May 25th, but the Israeli government kept saying, “We have to take into account the Americans. We have to see what the Americans will say.” And so, at every step along the way in June '67, it was the possibility of the Americans interposing themselves and forcing the withdrawal that was upper—an unconditional withdrawal—that was uppermost in the minds of the Americans. And also, Segev accurately quotes Israelis. Once the occupation began, the Israelis are concerned: How will the United States react in the event that this occupation begins to look like it's going to be permanent? What’s going to happen if Israel decides to annex Jerusalem? And I think Tom Segev has a very interesting account of how Israel was pretending only to extend administrative law to Jerusalem, because they’re fearful of the American reaction. The United States had huge leverage then, and the United States continues to have huge leverage today, in determining what Israel does or doesn’t do, and not only with regard to the Palestinians, but regionally.

AMY GOODMAN: Mona Farra, you are traveling the country in a tour, speaking yesterday. You spoke at the United Nations. What is the main message you have to people here in this country, in the United States?

DR. MONA EL-FARRA: The main message is that occupation, war, will never bring peace to the area. And only peace that is built on justice will bring settlement and peace to the area.

AMY GOODMAN: Tom Segev, as you come to this country, what do you think is the important message?

TOM SEGEV: I can agree with Mona. I think that particularly American friends of Israel should redefine their friendship for Israel. Friendship for Israel does not mean support the government at all times. And I think they should make a distinction between Israel and the government of Israel. Just as they do that for their own country, why not do it for Israel? There are many, many Israelis who object to the occupation. Nothing you will say in your rally in Washington will be new to Israeli ears. In fact, the public debate in Israel is much, much more open than it is in this country regarding the future of the territories. And so I think that it’s very important that people realize that friendship to Israel does not necessarily mean supporting occupation of the territories—on the contrary.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to have to leave it there. I thank you all for being with us, Tom Segev, author of 1967: Israel, the War, and the Year That Transformed the Middle East; Dr. Mona El-Farra, on a tour around the United States, with the Middle East Children’s Alliance, writes the blog, “From Gaza, with Love,” has grown up in and lives in Gaza; Norman Finkelstein, professor of political science at DePaul University. His book is Beyond Chutzpah: On the Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History, speaking to us from Chicago.

Media Options