Related

Topics

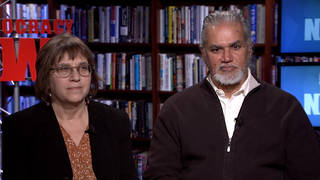

Guests

- Mary TillmanMother of Pat Tillman. Her new book is Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman.

Pat Tillman left behind a lucrative NFL contract to enlist in the military after 9/11. On April 22, 2004, Tillman was killed while serving in Afghanistan. He died, the military said, while charging up a hill toward the enemy to protect his fellow Army Rangers. But that wasn’t the real story. Tillman was killed by his own men. What’s more, the military knew that within hours but waited five weeks before admitting it. Four years and several probes later, Pat Tillman’s family, led by his mother Mary, are still searching for answers about what really happened. Mary Tillman has just published a book based on her review of uncensored government documents and her four-year effort to cut through misleading official accounts of how her son died. It’s called Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: He was perhaps the most famous American soldier of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Pat Tillman was an NFL star who left behind a $3.6 million contract with the Arizona Cardinals to enlist in the military after 9/11. His decision made headlines across the country and prompted then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld to send him a congratulatory note. On April 22, 2004, Pat Tillman was killed while serving in Afghanistan. He was twenty-seven years old.

Two weeks later, just before a nationally televised memorial service, the Pentagon awarded him the Silver Star. He died, the military said, while charging up a hill toward the enemy to protect his fellow Army Rangers. But that wasn’t the real story. Tillman was killed by his own men. What’s more, the military knew that within hours but waited five weeks before admitting it.

Four years later and after seven investigations, several inquiries and two congressional hearings, Pat Tillman’s family, led by his mother Mary, are still searching for answers about what really happened. Lawmakers granted Mary Tillman access to uncensored versions of some documents that were not available to journalists. She has just published a book based on her review of those documents and her four-year effort to cut through misleading official accounts of how her son died. It’s called Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman.

I spoke with Mary Tillman this week about the life and death of her son. I began by asking her how she first heard that Pat had been killed.

MARY TILLMAN: I first learned from my daughter-in-law. She told me that Pat had been killed. And, of course, we heard from the casualty report that he had been shot in the head getting out of a vehicle, he died an hour later in a field hospital. And then, when we had his memorial service, the Army gave a Navy Seal friend of Pat and Kevin’s a narrative to read that said that he was running up a ridgeline in an attempt to help a convoy of troops get through an ambush zone, and he was killed by the enemy.

But then, four weeks later, when Kevin, his brother, who was also in the same platoon but was not present when his brother was killed, he had gone back to Fort Lewis. He was taken aside by his first sergeant, and he was told that Pat was killed by friendly fire. I was told, however, by an Arizona Republic reporter, who called me assuming I knew already. And so, it was rather shocking to learn the news.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did the reporter tell you?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, he just said that the Army had indicated that Pat was killed by friendly fire, and what did I think? And I basically just sort of said, “I have nothing to say,” and I hung up.

And then, of course, the next day, my son, my daughter-in-law, my other son, the family gathered, and a battalion commander came to our house, and he explained what happened in Pat’s situation, that he was killed by soldiers in a vehicle that had come out of the ambush zone, and that the — he said the visibility was quite good, but he said that Pat and the AMF soldier that was also killed alongside Pat — he said that they were about 150 to 250 meters away. He said that the soldier in the vehicle actually got out of the vehicle. He shot the AMF soldier in the chest six to eight times. And when he did that, the other soldiers in the vehicle opened up on the ridgeline.

Pat and other — and the young soldier next to him and all the other friendlies on the ridgeline waved and yelled “Cease fire!” and tried to get their attention to get them to stop. Pat and the young soldier that was with him were kind of crouching between two rocks that were about thigh-high, and there was shrapnel flying everywhere. And they were trying to, you know, wave their arms to say “Cease fire!” The regular ceasefire signal would not have been able to be seen while they’re crouching behind rocks, so everyone’s waving their hands. The soldiers continued to shoot, so Pat threw a smoke grenade, thinking that by throwing that the soldiers would recognize there had to be friendlies in the area.

At that point, the firing did stop. And so, Pat and the young soldier stood up. The other soldiers on the ridgeline relaxed. And Pat walked — started to walk around the rock, and all of a sudden they opened up again. We think that Pat was then hit in the chest. We know he was hit in the chest, but we think it was at this point that he was hit in his body armor. It would have knocked him to the ground, to his knees. And at that point, he was hit by a three-round burst and killed.

The soldiers in the vehicle then drove down the ridgeline, continuing to shoot. They ended up shooting at structures that were at the side of the road, and they wounded their platoon leader and the radio operator. In fact, we were told that they were shooting so wildly and out of control that they nearly shot the vehicle behind them that was coming out of a canyon.

AMY GOODMAN: And at this point, how have you pieced all of this together? Certainly, the men in his unit knew what had happened at that moment, didn’t they?

MARY TILLMAN: Yes, many of the soldiers did. The ones on the ridgeline were pretty clear that — actually, the soldier next to him and one of — several of the soldiers behind him knew he was killed by the soldiers in this vehicle. The rest of the ones on the ridgeline suspected it, but, you know, some of the soldiers were not — did not know.

Kevin did not know. He was fifteen minutes behind his brother when this happened. And so, he was told that he was killed by the enemy also. But, of course, at that moment when he first arrived on the scene, it wouldn’t have served anyone’s best interest to tell Kevin right away. But the fact is, they never told him until, you know, four weeks later, when in fact they all knew.

And of course, in this scenario, they did say, like I said, that Pat and the MF were 150 to 250 meters away, but in fact they were probably thirty to forty — thirty-five to forty meters away. We were told that the MF was shot when he was standing, in that original story, but three weeks —-

AMY GOODMAN: This is the Afghan soldier?

MARY TILLMAN: The Afghan soldier, who was a friendly. He worked alongside these troops for two weeks. We were told that he was standing when he was shot. However, when we got to Fort Lewis for the official briefing, they said that “Oh, no, he was in a prone position.” In other words, they were trying to make it appear as though the soldiers in the vehicle could not have identified him as a friendly, because he was wearing an American uniform. But the problem was, he was shot in the chest. So how do you shoot a man six to eight times in the chest if he’s in a prone position?

AMY GOODMAN: So, who do you think is responsible for this cover-up?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, I -— you know, the Army has told us that it was a three-star general, a General Philip Kensinger, that was responsible for not telling the family, for covering up. But I talked to retired General Wesley Clark, and he said, after looking at the documents, he said that there is no way that this started at the three-star level. In fact, he went on Keith Olbermann last summer, and he said that this cover-up started at a much higher level than a three-star level.

I think that it most likely started with the former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. He had written Pat a letter when he enlisted, thanking him for enlisting, so Pat was in his radar. We were also kind of shocked to discover in August at the second congressional hearing that Rumsfeld sent a snowflake memo — I guess he opposes email, so he tends to write things and drop them off on people’s desks. And this memo was to the then-Deputy Secretary of the Army, Peter Geren, who is now the Secretary of the Army. And this memo basically said, you know, that Pat’s a very special person and that they should keep an eye on him.

So it’s ludicrous to think that the generals in the chain of command who, through the documents we know, learned of Pat fratricide within twenty-four to forty-eight hours — it’s ludicrous to think that they didn’t tell the Secretary of Defense, because Rumsfeld would have — heads would have rolled if they didn’t tell Rumsfeld. I mean, this was the month the Abu Ghraib prison scandal broke. In fact, it was the same week Pat died. Fallujah was in chaos. President’s approval rating was very dismal. And, of course, this was the worst month in the war to that point in Iraq in terms of casualties. So, for them not to tell him that Pat was killed by friendly fire, that just wouldn’t have happened, in my mind, because he was — he’s known to be a micromanager. He’s also known to want hands-on with the military, especially the Special Operations and the Black Ops.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Donald Rumsfeld, in his first testimony after he was no longer Defense Secretary but brought in by the House to address this issue, the death of your son, responded, “I know I would not engage in a cover-up. I know no one in the White House suggested such a thing to me. I know the gentlemen sitting next to me are men of enormous integrity and would not participate in something like that,” he said.

MARY TILLMAN: Right. Well, I think he was being very disingenuous. I didn’t believe him then. I still don’t believe him.

AMY GOODMAN: Why do you think they didn’t tell the truth? Why do you think Rumsfeld lied?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, because once you tell a lie, it’s very hard to say you lied. And I think that the lie is planted, and they’re not going to say otherwise. But I think that Pat’s death was used by the administration, by the military, to deflect, you know, Abu Ghraib, to deflect Fallujah, to deflect all these things. They saw an opportunity to use him.

In fact, there is a General Yellen, in his testimony to General Jones, who was the third investigative officer — or, pardon me, yeah, the third general, actually, or the third officer to investigate Pat’s death — he asked General Yellen, “What was the tone, basically, of the chain of command once they learned that Pat’s death was of fratricide?” And of course, you know, they did know within twenty-four to forty-eight hours that it was at least a suspected fratricide. He said, “Well, it’s like we were given a steak dinner, but they handed it to us in a garbage can cover. You got it, you work it.” In other words, Pat’s death, to them, was a positive thing, because they could use him to promote patriotic feeling for the war. But he was killed by friendly fire, so they were going to have to spin the story.

AMY GOODMAN: Mary Tillman is Pat Tillman’s mother. Pat Tillman, the Army Ranger, he was an NFL star, killed April 22nd, 2004 in Afghanistan. Mary Tillman’s book is called Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman. We’ll come back to this conversation in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to my interview with Mary Tillman, the mother of the NFL star turned Army Ranger Pat Tillman, killed in Afghanistan April 22nd, 2004, by members of his own unit. The Army had initially claimed Tillman was killed by enemy fire while leading troops into battle. The story was widely reported in the media before the military was forced to acknowledge the false claim.

Last year, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform convened a hearing to look into the Pentagon’s role in the case. Pat Tillman’s brother Kevin was among those who testified. Kevin was an Army Ranger, as well, in Pat’s unit in Afghanistan when his brother was killed. This is some of Kevin’s testimony before Congress.

KEVIN TILLMAN: April 2004 was turning into the deadliest month to date in the war in Iraq. The dual rebellions in Najaf and Fallujah handed the US forces their first tactical defeat, as American commanders essentially surrendered Fallujah to members of Iraq resistance. And the administration was forced to accede to Ayatollah Sistani’s demand for January elections in exchange for assistance in extricating US forces from its battle with the Mahdi militia. A call-up of 20,000 additional troops was ordered, and another 20,000 troops had their tours of duty extended. In the midst of this, the White House learned that Christian Parenti, Seymour Hersh and other journalists were about to reveal a shocking scandal involving massive and systemic detainee abuse in a facility known as Abu Ghraib.

Then, on April 22nd, 2004, my brother Pat was killed in a firefight in eastern Afghanistan. Immediately after Pat’s death, our family was told that he was shot in the head by the enemy in a fierce firefight outside a narrow canyon. Revealing that Pat’s death was a fratricide would have been yet another political disaster during a month already swollen with political disasters and a brutal truth that the American public would undoubtedly find unacceptable, so the facts needed to be suppressed. An alternative narrative had to be constructed.

Crucial evidence was destroyed, including Pat’s uniform, equipment and notebook. The autopsy was not done in accordance to regulation, and the field hospital report was falsified. An initial investigation, completed eight to ten days before testimony could be changed or manipulated and which hit disturbingly close to the mark, disappeared into thin air and was conveniently replaced by another investigation with more palatable findings. This freshly manufactured narrative was then distributed to the American public, and we believe the strategy had the intended effect. It shifted the focus from the grotesque torture at Abu Ghraib and a downward spiral of an illegal act of aggression to a great American who died a hero’s death.

Over a month after Pat’s death, when it became clear that it would no longer be possible to pull off this deception, a few of the facts were parceled out to the public and to our family. General Kensinger was ordered to tell the American public May 29th, five weeks later, that Pat died of fratricide, but with a calculated and nefarious twist. He stated, quote, “There was no one specific finding of fault,” end-quote, and that he, quote, “probably died of fratricide,” end-quote. But there was specific fault, and there was nothing probable about the facts that led to Pat’s death.

The most despicable part of what General Kensinger told the American public was when he said, quote, “The results of this investigation in no way diminish the bravery and sacrifice displayed by Corporal Tillman,” end-quote. This is an egregious attempt to manipulate the public into thinking that anyone who would question this 180-degree flip in the narrative would be casting doubt on Pat’s bravery and sacrifice. Such questioning says nothing about Pat’s bravery and sacrifice, any more than the narrative for Jessica diminishes her bravery and sacrifice. It does, however, say a lot about the powers who perpetrated this.

After the truth of Pat’s death was partially revealed, Pat was no longer of use as a sales asset and became strictly the Army’s problem. They were now left with the task of briefing our family and answering our questions. With any luck, our family would sink quietly into our grief, and the whole unsavory episode would be swept under the rug.

However, they miscalculated our family’s reaction. Through the amazing strength and perseverance of my mother, the most amazing woman on earth, our family has managed to have multiple investigations conducted. However, while each investigation gathered more information, the mountain of evidence was never used to arrive at an honest or even sensible conclusion.

The most recent investigation by the Department of Defense Inspector General and the Criminal Investigative Division of the Army concluded that the killing of Pat was, quote, “an accident.” The handling of the situation after the firefight were described as a compilation of, quote, “missteps, inaccuracies, and errors in judgment which created the perception of concealment.”

The soldier who shot Pat admitted in a sworn statement that just before he delivered the fatal burst from about thirty-five meters away, that he saw his target waving hands, but he decided to pull the trigger anyway. Such an act is not an accident. It’s a clear violation of the rules of engagement.

Writing up a field hospital report stating that Pat was, quote, “transferred to intensive care unit for continued CPR,” after most of his head had been taken off by multiple .556 rounds, is not misleading. Stating that a giant rectangle bruise covering his chest that sits exactly where the armor plate that protects you from bullets is being, quote, “consistent with paddle marks” is not misleading. These are deliberate and calculated lies.

Writing a Silver Star award before a single eyewitness account is taken is not a misstep. Falsifying soldier witness statements for a Silver Star is not a misstep. These are intentional falsehoods that meet the legal definition for fraud. Delivering false information at a nationally televised memorial service is not an error in judgment. Discarding an investigation that does not fit a preordained conclusion is not an error in judgment. These are deliberate acts of deceit.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Pat Tillman’s younger brother, Kevin Tillman, in the same unit in the Rangers in Afghanistan, testifying, though, on April 24th, 2007. So, Mary Tillman, your son says crucial evidence was destroyed, including Pat’s uniform, equipment and notebook; the autopsy not done according to regulation; the field hospital report was falsified. Go through each of these allegations.

MARY TILLMAN: Well, Pat’s uniform was destroyed. His equipment was destroyed. And of course, there is a protocol that the military has that the uniforms and equipment of fallen soldiers, especially soldiers killed by fratricide, suicide or suspected execution, need to go back to the medical examiner. I mean, they prefer to have all of the uniforms from any fallen soldier, but because Pat was a suspected fratricide, definitely his things should have gone back with him. And we were told that his body — or, pardon me, that his equipment and uniform was a biohazard. I mean, that’s why they destroyed his things. But Pat’s body would have been considered a biohazard, and yet his body was very well preserved when it got bad to Rockville, Maryland. In fact, the medical examiner said in his testimony that Pat’s body was well preserved. If his uniform had been left on him, it would have also been well preserved. And I think that it’s because his uniform had evidence of American rounds that they destroyed it.

We also were suspicious of the autopsy, because initially when we got it, it read like it wasn’t even Pat. He was documented to being two inches taller than he was. The autopsy said that he was wearing a gold wedding band, when in fact his wedding band was platinum, which would have appeared more silver. He had some identifying scars on his body and various things that were not identified in the autopsy. So we became suspicious of that.

Then I came upon a portion of the autopsy that said that there was a — there were marks on his chest that looked consistent with an attempt to defibrillate him. And that didn’t make sense to us, because basically the autopsy said Pat virtually had no brain when he — after he was killed. So it didn’t make sense that someone would try to save him. And, of course, Kevin already knew that the medic who got to Pat first made no attempt to save him initially. And if that — that would be the time that someone might in a panic try to save someone. But Pat had been bagged as KIA, and he had been dead for about two hours before he got to the field hospital. So it didn’t seem like anyone would have attempted to defibrillate him.

So when I talked to the medical examiner and the coroner, they said that simply that is what it looked like, but they weren’t sure. They said I should probably ask for the field hospital documents. So it took six months to get the field hospital documents. Once we got those, it was kind of surprising, because there was no mention of defibrillation, but they said that he — that CPR was performed on him, that he was transferred to ICU for continued CPR. And that made us even more perplexed and outraged, because, as I said, here is a soldier who had been dead for two hours, he had no brain, and yet they’re saying they performed CPR on him and transferred him to ICU for continued CPR. So all of these things, you know, were very upsetting to us, and we had to keep looking into it further.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to play for you a member of the unit who I met in Santa Barbara, California. His name is Peter Boris [phon.], and I asked him about what happened to Pat and what happened with the cover-up.

PETER BORIS: My name is Peter Boris. I was with 2nd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. And the day Pat was killed, I was with his platoon earlier in the day, and then our platoon drove back to the firebase. This is on the eastern border of Afghanistan. We made it back to the base about sundown. And we got — heard over the radio that Pat’s platoon had gotten ambushed and that one of the brothers had been killed. So we jumped back in our trucks and drove out there, but we didn’t get there ’til dawn. It was that far, so… And then we started — we replaced their platoon and started searching for the people who did the ambush.

AMY GOODMAN: And when did you figure out that it was —-

PETER BORIS: Friendly fire?

AMY GOODMAN: Friendly fire, exactly.

PETER BORIS: I found out a few days later that it was friendly fire. Once we got -— once we finished arresting a bunch of people and came back to the firebase, I found out through one of my buddies. And at the time, actually, I was all for keeping it a secret, which is interesting. I was thinking about how I would want my parents to think that I was killed by, you know, the enemy, rather than wasted by your own friends. So I was like, yeah, I wouldn’t tell the parents, either. It’s more honorable that way.

AMY GOODMAN: What happened to the Afghans who you arrested?

PETER BORIS: I don’t know. We go into a — well, first of all, we’d go into a village, find out — we’d bribe people to tell us where the terrorists were and then go into their village at night, kick in their door, arrest all the men and ignore the women and children.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean, “bribe people”? You give them money?

PETER BORIS: We give them a generator or school supplies or maybe cash. I wasn’t part of that. I was a foot soldier, so I don’t know the details. But as far as I could tell, that’s how it worked. And then we’d handcuff all the males. We’d have one of the people that we had take us there to identify who was good and who was bad, and then we’d take the people who were identified as bad on the trucks back to the firebase. And you never saw them again.

AMY GOODMAN: How could you trust them? How did you know who the people were who were pointing the finger at others?

PETER BORIS: That wasn’t my job, and I have no idea. And that was always a question I had, but that was up to the —- up to the intelligence people, the platoon leaders and -—

AMY GOODMAN: And did you change your mind about whether Pat’s family should be told the truth?

PETER BORIS: Yeah. Since then, I’ve decided usually the truth is the best in most every situation, so…

AMY GOODMAN: How did his death affect your unit? How did it affect you —-

PETER BORIS: Sure. It was a -—

AMY GOODMAN: — in the long term?

PETER BORIS: It was a pretty big blow, especially initially. I saw a lot of guys get really angry and start to feel a lot more hatred for just local people. Me, personally — I don’t know — I dealt with it fine. It was pretty amazing that he would die, out of everyone, because we heard about him in basic training, like some NFL player giving up a $5 million contract. We couldn’t believe it. And then he ended up in my unit.

AMY GOODMAN: When you said they got mad at local Afghans, didn’t everyone know that he was killed by what you call friendly fire?

PETER BORIS: No, this was initially. We had just gotten out there, and we hadn’t heard anything about what had happened. We patrolled around the area. We saw the blood and the shells, but we didn’t know the details of it. And then we went out up the valley more and started searching the villages. So we had no idea what happened. I didn’t find out ’til days later. And even most of the guys in the platoon didn’t know it was friendly fire for a while.

AMY GOODMAN: Peter Boris was in the same unit as Pat Tillman. Mary Tillman is with us, Pat Tillman’s mother. Your response to Peter talking about first believing you shouldn’t know, sort of protecting you, but then changing his mind?

MARY TILLMAN: Yeah, I mean, a lot of soldiers actually had said that, that the — and I’ve had grown men and women say, “Well, wouldn’t you just rather think of him as dying by the enemy?” I frankly don’t think it’s dishonorable to be killed by friendly fire. I mean, I’d say quite a few soldiers are killed by friendly fire. I don’t think it’s dishonorable. They’re honorable because they’re there and they died. Is it honorable — is it dishonorable to die if you’re hit by a car? I mean, I don’t understand that rationale.

But the other problem with lying for the benefit of making a glorious story is when the evidence points to a different direction, and then that becomes very disturbing for a family. It’s always best to tell the truth. And I do know that some of the soldiers were aware that it was, you know, a fratricide, and some of them were not aware of it. And it took several days before, you know, a lot of the soldiers that were in Afghanistan in that area to found out.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the memo you uncovered from Lieutenant General Stanley McChrystal?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, I didn’t really uncover it. Actually, somebody sent that memo anonymously to an Associated Press reporter. And I had this memo emailed to me by a person who works at Senator Barbara Boxer’s office.

And what is so amazing about this memo is the memo was used by the media to point out basically — or, I don’t know if it was used by the media. I shouldn’t say that. Someone pointed out to the media, I suppose, that this memo was a means of exonerating Stanley McChrystal for having any kind of, you know, culpability in any kind of cover-up, because on April 29th he sent this P4 memo — it’s a personal memo — to General Abizaid, General Kensinger and General Brown, indicating that Pat was indeed killed by friendly fire or at least suspected friendly fire, although he’s playing with language there, because they did know that it — they suspected it within twenty-four hours, but by April 29th they knew. But he’s saying that they should tell the President and the Secretary of the Army, because they were going to be making speeches at the President — at the correspondents’ dinner that weekend and that they didn’t want him or the Secretary of the Army to make any embarrassing statements about Pat’s actions “if” the circumstances of Pat’s death were to become public, not “when” the circumstances become public, but “if,” which suggests that they had no intention of telling us the truth unless they had to.

He also has in there an example of how they can word the narrative in the Silver Star and get away with it, in the sense that Pat was killed by friendly fire, not the enemy. And, of course, the Silver Star narrative is supposed to be rather specific about a soldier’s actions. And so, he’s actually giving them an example of language they can use to falsify the Silver Star.

But the military somehow kind of presented this to the press in a manner that left them to believe that this was exonerating Stanley McChrystal. He’s trying to be a good guy. He’s trying to tell the President, you know, that — and other officers that Pat was killed by friendly fire, but they all suspected it already.

AMY GOODMAN: The exact quote at the end of his memo to the higher-ups, the memo that he was concerned President Bush and the Secretary of the Army might mention his heroic death in upcoming speeches, Pat’s death, says, “I felt it was essential you receive this information as soon as we detected it, in order to preclude any unknowing statements by our country’s leaders which might cause public embarrassment if the circumstances of Corporal Tillman’s death become public.”

MARY TILLMAN: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You have other emails.

MARY TILLMAN: I have other emails. I have some emails that, you know, the speechwriters and different people were sending back and forth. One of the emails refers to Pat’s Silver Star. The subject in the email says, you know, “Tillman Silver Star game plan,” or something to that effect. And it’s like, if you’re giving a soldier a Silver Star, why do you need a game plan for it? You know, that was very, very suspicious to us.

And, of course, Rumsfeld’s speechwriter and the President’s speechwriter had sent emails to the military wanting to get specific information, of course, about the way Pat died, and that was on April 28th. And so, it’s interesting that, you know, Stanley McChrystal sent his email on April 29th in order to make sure that, you know, everything was — you know, that they didn’t make any errors in talking about it. But I do think that they already knew Pat’s death was suspected fratricide. This email was simply to let them know, yes, indeed, it was a fratricide, because the statements we have from these high-ranking generals indicate they knew within twenty-four to forty-eight hours.

And in fact, when we were at the congressional hearing in August, one of Representative Waxman’s attorneys called me the night before the hearing, and he was very encouraged, because when he interviewed General Myers, who worked with Rumsfeld at the Pentagon, he asked him if the Pentagon was aware of Pat’s death being a friendly fire, and he suggested basically that everyone was aware of what happened. But when he got on the panel at the congressional hearing and his former boss was sitting next to him, he denied saying that.

AMY GOODMAN: We’ll return to my conversation with Mary Tillman in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to Mary Tillman, mother of Pat Tillman, the Army Ranger killed in Afghanistan four years ago. I asked Mary to talk about the soldiers with Pat, whose written accounts of what happened were changed.

MARY TILLMAN: Private Bryan O’Neal and also a Sergeant Matt Weeks, both of them were actually told to type out a narrative of what they — you know, what they know happened to Pat or what they — you know, their version of what happened to Pat, because they were the two closest soldiers to him at the time. And they did. They wrote down what happened. And then, it turns out, someone went in and changed their statements and changed their narratives, so when they wrote the Silver Star, it appeared as though Pat were killed by the enemy. And this all came out at the congressional hearing.

AMY GOODMAN: So both of them knew from the beginning. Both Matt Weeks and Bryan O’Neal knew that he was killed by fratricide?

MARY TILLMAN: Exactly. Yes, they did.

AMY GOODMAN: Who changed their testimony?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, they’ve never been able to trace that. No one knows, and no one is trying very hard to find out.

AMY GOODMAN: You talk about that day, April 22nd, 2004, and the orders that a lieutenant received. I don’t know if I’m pronouncing his name right: David Uthlaut.

MARY TILLMAN: Uthlaut.

AMY GOODMAN: Uthlaut. Explain what happened on that day, why your son Pat was where he was in Afghanistan.

MARY TILLMAN: Well, to the best of my understanding of it, you know, the military was supposed to, on the orders of the Secretary of Defense, be — you know, he had a matrix. And basically, these missions, they were supposed to go into these villages and detect insurgents and try to weed them out.

In this case, the platoon had been stranded in a town called Magarah, or a village of Magarah, for about six hours because of a broken Humvee. And the commanders that were in the tactical operations center were getting frustrated, because it was holding up the mission to have this Humvee detaining these troops. Uthlaut and some of the other officers involved in the platoon wanted to get rid of the Humvee or leave it behind, but they weren’t able to do that. They were told they had to take it somewhere to get it repaired. Uthlaut wanted to have maybe it airlifted out, but they didn’t have the right type of helicopter that could airlift this Humvee out at the time, so they were told to drag it to the Khost highway, which was, you know, quite a few miles north of where they were.

And they also wanted, however, boots on the ground in Manah by dusk. So Uthlaut suggested that the platoon travel as one unit and take the Humvee and drop it off, and then they would all travel as one unit to the city of Manah. But the officers at the top insisted that they actually split the platoon, have one part of the platoon deliver the Humvee, and then they would meet up with the other portion of the platoon later to then go into Manah. And they told him that they had to have boots on the ground in Manah by dark or before dark. And Uthlaut protested this also, because ordinarily they were trying to avoid traveling in the daylight hours, because it was so dangerous. Another soldier, a soldier Jay Blessing, had been killed by an IED in the month of November 2003, and so they sort of established a protocol that they wouldn’t be moving during daylight hours.

So on two levels, he was protesting this mission. He didn’t want to split the troops, and he didn’t want to move them during daylight hours. And you have to keep in mind that Lieutenant Uthlaut was a first captain of his class at West Point, which is essentially he’s the valedictorian of his class. He was a very intelligent young man, and he was protesting vehemently these orders. And I’ve heard that ordinarily it’s the soldier on the ground, the officer on the ground that has the last word, and the fact that the officers at the tactical operations center paid no attention to his protest is very disturbing.

AMY GOODMAN: Mary Tillman, why did Pat join the military? Why did he become a Ranger? Tell us a little about your son.

MARY TILLMAN: Well, you have to understand, my son was twenty-five when he enlisted. He was a married man. I don’t know all his reasons for doing what he did. I mean, you know, he’s his own person. I do know that 9/11 greatly affected him and his brother, as it did most of us. It was quite disturbing to him, and he felt that his football career was very superfluous at this point. And he knew that other young people were enlisting, and he felt he should, you know, serve his country. Beyond those reasons, I can’t really speak to that. I don’t speak for him.

AMY GOODMAN: You describe in the book when Kevin called you to tell you that he and Pat were enlisting.

MARY TILLMAN: Mm-hmm.

AMY GOODMAN: What was your conversation? Had you talked before about this possibility?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, Kevin had talked about enlisting at various points, even before the September 11th attacks, but just casually. Like a lot of young men, you know, he was curious about the military and serving. And so, we had had that conversation. And of course there’s lots of military in my family, so they were used to talking about the military. They’re both history buffs. So, you know, it really wasn’t that shocking that they would enlist, but I was just — and I was proud of them for wanting to serve their country.

What bothered me most is the — you know, the leadership at the helm at this time. I didn’t have great trust in the Bush administration, even at that point. And that concerned me, and I talked to them about that. And of course, they didn’t disagree with me. But they also said you cannot choose your leaders when you’re — you know, at that point, you’re stuck with the leaders you have when you’re in a national crisis. And they could only hope that our leaders would make appropriate choices in a time like this.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Mary Tillman, Pat Tillman’s mother. Pat Tillman, the Army Ranger, was killed April 22nd, 2004 in Afghanistan. Mary, how many investigations have taken place, and who has conducted them? Who has been found responsible at least until this point?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, there’s been two — actually three military — well, OK, initially there were three military investigations. Then there was an investigation by the Inspector General’s office, and they deemed that there should have been a criminal investigation, which should have taken place right after Pat died. But they really didn’t start it ’til almost two years after his death. So then the criminal investigation was conducted. After that, after the hearing and everything, there was an investigation done by the Army again to look into the officers who were culpable in possibly not doing their job correctly. And then, I believe, the Secretary of the Army conducted another investigation, because I said that I didn’t believe a lot of my questions were answered. So he did another investigation looking into those questions, which I still don’t have satisfactory answers for. So there have been a number of investigations.

And there is just — the bottom line is, no one has been held accountable for anything. There have been people that have had some slaps on the wrist for doing certain things, but — and some people have just been scapegoated.

AMY GOODMAN: General Philip Kensinger was reprimanded. What happened to him? And what do you believe is his role?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, I think that the General was probably culpable in this, but I don’t think he’s the ultimate bad guy that, you know, the military would like us to believe. I think he has been a definite scapegoat. I’ve been told just recently that there has been no closure yet in terms of the reprimand or the so-called punishment that he’s supposed to receive. I heard that he was going to be docked a rank or something or stripped of one of his stars, which would also have an effect on his retirement or something like that. But I just don’t think that he is the one that’s ultimately responsible for this cover-up. And, you know, as I said, retired General Wesley Clark also said that this cover-up goes much higher than the three-star level.

AMY GOODMAN: As you wrote this book, Mary, Boots on the Ground by Dusk, your tribute to Pat Tillman, did anything surprise you? You had done so much research leading up to this, but in actually piecing this together?

MARY TILLMAN: Not to the point that I started writing it. I don’t think anything was terribly shocking. And I think that most of it I pretty much had settled in my mind when I started writing it, although, of course, I was in the middle of writing it during the congressional hearings, so the fact that — you know, that the oversight committee, the congressional oversight committee, deemed there was a cover-up was very validating, and we were very encouraged by that. But unfortunately, as I’ve said, you know, through the whole interview, there has been no real closure, no real accountability.

AMY GOODMAN: What exactly do you want to happen right now?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, I would like someone to be held accountable. I’d like for them to discover and try to discover who was involved with this cover-up. It’s a horrible thing that they did. And I think that if people don’t see that, it’s very sad, because it means that we have been numbed to all the lies and deceptions that we’ve been faced with during these last eight years.

The government used a young man’s death for propaganda. They did that with Jessica Lynch, as well. It’s a pattern of behavior they have. Jessica Lynch could have died, because they wanted to videotape her rescue. There’s nothing that can be more horrific than that. And that also came out in our congressional hearing, because there was a dual purpose, to check her situation and Pat’s. And so I —

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to a clip of Jessica Lynch testifying. This was just last year in the House.

JESSICA LYNCH: At my parents’ home in Wirt County, West Virginia, it was under siege by media, all repeating the story of the little girl Rambo from the hills of West Virginia who went down fighting. It was not true. I have repeatedly said, when asked, that if the stories about me helped inspire our troops and rally a nation, then perhaps there was some good. However, I’m still confused as to why they chose to lie and try to make me a legend, when the real heroics of my fellow soldiers that day were legendary: people like Lori Piestewa and First Sergeant Dowdy, who picked up fellow soldiers in harm’s way, or people like Patrick Miller or Sergeant Donald Walters, who actually did fight until the very end.

The bottom line is the American people are capable of determining their own ideals for heroes, and they don’t need to be told elaborate lies. I had the good fortune and opportunity to come home and to tell the truth. Many soldiers, like Pat Tillman, they did not have that opportunity. The truth of war is not always easy. The truth is always more heroic than the hype.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Jessica Lynch. Mary Tillman, your response to what she had to say, and what you think are the parallels between what happened to Jessica Lynch and what happened to your son?

MARY TILLMAN: I believe that she made it very clear that, you know, the soldiers are heroes in their own right. And there are heroes out there, and you don’t have to fabricate heroes. I thought that was a very, you know, remarkable statement, and so true. And, you know, she also indicated that she had these horrific injuries, and of course the Iraqis did the best to take care of her, to her mind, and they tried to return her to the US, and they wouldn’t take her. And it turns out, what was uncovered in the hearing is that they wanted to have this dramatic rescue videoed. So at the point they could have saved — you know, gone in to rescue her, the military held off for twenty-four hours to get a video crew in there. And what’s very ironic is that Pat and Kevin were also involved in this rescue. They, of course, believed that it was a legitimate rescue and that they were in great danger. But it turns out that it was more or less staged.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain.

MARY TILLMAN: Well, it was planned that they were going to go in. There was really no harm. The soldiers were under the impression that the Republican Guard was going to be at the airport. I mean, they really did fear for the situation. But as it turned out, the Republican Guard had already taken off. It was not as dangerous a situation as they were led to believe. And of course, in the hearing, they determined that this rescue was held off for twenty-four hours so a video crew could get in and take pictures of the rescue.

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re saying that Kevin and Pat were a part of that rescue?

MARY TILLMAN: They were part of the rescue, in the sense that, as Rangers, they kind of held the perimeter of the Baghdad airport. They were part of that. They didn’t go in and actually take her out, no.

AMY GOODMAN: Did they write back to you, or has Kevin talked to you about what he feels in that situation?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, I don’t speak to what Kevin knows. That’s — I will not divulge that. And he was not supposed to divulge that. They were not supposed talk about that at the time to us. We learned some things later, but I won’t speak to what Kevin told me.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, Mary Tillman, the role of the media?

MARY TILLMAN: Well, the media has been obviously helpful. I mean, a lot of this information — most of this information could never get out without the help of the media. But I also feel like the media has been very frustrating to us at times. But, you know, ultimately, you know, it’s been helpful. But I think that the media has not been aggressive enough with this administration. I think that they need — especially the television media. The print media at times can be fairly hard on them, but I think the television media, especially the press corps, you know, the presidential press corps — I mean, I think they go way too easy on this administration.

AMY GOODMAN: Has then-Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, has President Bush attempted to meet with you?

MARY TILLMAN: No, never.

AMY GOODMAN: Your son was perhaps the most famous soldier to go to Iraq or Afghanistan.

MARY TILLMAN: That’s right. And of course, as I mentioned, Rumsfeld did send Pat a letter thanking him for enlisting, but we never did hear from him after Pat was killed.

AMY GOODMAN: Mary Tillman’s book is called Boots on the Ground by Dusk: My Tribute to Pat Tillman. She and her family are still seeking the truth about Pat’s death.

Media Options