Topics

Guests

- Twa-le AbrahamsonYouth coordinator and a founding member of SHAWL (Sovereignty, Health, Air, Water, Land) Society, a grassroots organization whose major focus involves developing community education and strategies to address impacts of radiation exposure due to over fifty years of uranium mining on the Spokane Reservation.

We speak with Twa-le Abrahamson of the Spokane Indian Reservation, where the only uranium mining in Washington State took place. She helped found the SHAWL (Sovereignty, Health, Air, Water, and Land) Society, which addresses the impact of radiation exposure caused by over fifty years of uranium mining in the area. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We go now from the contaminated Hanford nuclear site to a key part of nuclear weapons production and nuclear power generation: uranium mining.

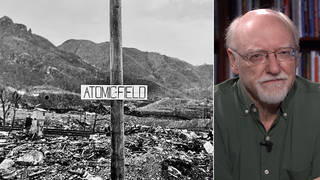

My next guest is Twa-le Abrahamson. She is with the Spokane Indian Reservation, where the only uranium mining in Washington State took place. The two mines on the reservation, Sherwood Mine and Midnite Mine, have not been active since the ’80s, and the Midnite Mine was declared a Superfund site in 2000. The mine was operational from 1955 to ’81 and now contains several open pits filled with heavy radioactive metals and water.

Midnite Mine was operated by a subsidiary of the Denver-based Newmont USA Limited, one of the largest mining corporations in the world. It’s long refused to pay for the cleanup of the mine. But last year the Environmental Protection Agency won a lawsuit that requires Newmont and its subsidiary, Dawn Mining Company, to help pay for cleaning up the abandoned mine.

Twa-le Abrahamson and her mother Debbie have founded the SHAWL Society, which stands for Sovereignty, Health, Air, Water and Land. It’s a grassroots organization addressing the impact of radiation exposure caused by over a half-century of uranium mining on the Spokane Reservation.

Twa-le Abrahamson, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s good to have you with us.

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: What are the issues you’re facing right now on the reservation?

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: Well, definitely the environmental impacts have been devastating to the land out there. There’s, you know, once were mountains, it’s gone, and it’s piles of waste rock that are left over. And for twenty years, during the first twenty years of operation, the mine ran without any water treatment at all. And so, in 1981, they finally started treating the water. And now, even with the cleanup plan that’s estimated at about $280 million, it’s treatment in perpetuity. So this, you know, will never be totally rid of this environmental impacts. And then that also impacts the culture of the tribe, because we do rely on subsistence, and so fishing and hunting in that area.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us about the Spokane Reservation, Spokane Indians, and the years of the uranium mining. How many were involved in the mining?

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: The Spokane Reservation is about forty-five miles northwest of the city of Spokane. And when the mines opened, the workforce was largely tribal people, and a lot of women worked in the mines at that time. And so, we’ve heard a lot of stories of women that worked there that were placed in certain positions because they were over childbearing age. And we’ve lost a lot of our people to illnesses related to — which we feel are related to the mine and the contaminants at the mine.

AMY GOODMAN: Why was it mainly women in the mines?

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: It wasn’t mainly women, but there were a lot of women that worked there.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you think needs to be done now?

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: Well, you know, we’re gradually making steps towards the cleanup. And I think just as long as, you know, the company and everybody maintains cooperation and works together to get the site as cleaned up and get it contained as possible and make it safer for our community.

AMY GOODMAN: What is your relationship with Newmont Mining?

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: Not great. You know, they fought it all the way. And so, this recent decision is kind of a big one, because they’ve definitely had the legal resources to fight. Even though they could have used it towards cleaning up the site, they chose to fight their involvement in the first place. So —-

AMY GOODMAN: Your mother is in Alaska right now for the Indigenous Peoples’ Global Summit on Climate Change?

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: Yes. And so, that’s also, you know, one of the things we look at beyond our own community, and it’s the effect that, you know, nuclear power has all the way down the chain. And so, that nuclear power isn’t the save-all to global warming.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s interesting that she’s in Alaska, because Sarah Palin -— as we travel today, we’re going to be going to Sandpoint, Idaho, and then we’re moving on to Montana. But that area, Sandpoint, is where Sarah Palin is from.

TWA-LE ABRAHAMSON: Oh, yeah.

Media Options