Topics

Guests

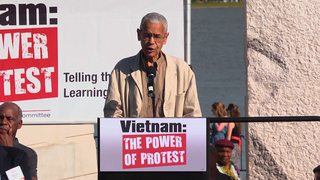

- Julian Bondleading civil rights activist and chair of the board of the NAACP since 1998. He helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center, and was a state legislator in Georgia for over two decades.

- Patricia Sullivanteaches history at the University of South Carolina and fellow at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard University. Her latest book is titled Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP, the country’s oldest and largest civil rights organization, had its 100th anniversary celebrations last week. The biggest event of the week was President Obama’s address in Harlem Thursday night. Thousands were in the audience as the President gave his first major speech on race since taking office. We take a look at the history and future of the NAACP with longtime NAACP board chairman Julian Bond and with historian Patricia Sullivan, author of Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the country’s oldest and largest civil rights organization, had its hundredth anniversary celebrations last week here in New York. The biggest event of the week was President Obama’s address on Thursday night. There were thousands in attendance as the President gave his first major speech on race since taking office. In his nearly forty-minute address, Obama outlined the present-day barriers African Americans face and ways to overcome them, citing his own personal journey and the courage and perseverance of countless civil rights activists who came before him.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: We know that too many barriers still remain.

We know that even as our economic crisis batters Americans of all races, African Americans are out of work more than just about anybody else — a gap that’s widening here in New York City, as a detailed report this week by Comptroller Bill Thompson laid out.

We know that even as spiraling healthcare costs crush families of all races, African Americans are more likely to suffer from a host of diseases but less likely to own health insurance than just about anybody else.

We know that even as we imprison more people of all races than any nation in the world, an African American child is roughly five times as likely as a white child to see the inside of a prison.

We know that even as the scourge of HIV/AIDS devastates nations abroad, particularly in Africa, it is devastating the African American community here at home with disproportionate force. We know these things. […]

We’ve got to say to our children, yes, if you’re African American, the odds of growing up amid crime and gangs are higher. Yes, if you live in a poor neighborhood, you will face challenges that somebody in a wealthy suburb does not have to face. But that’s not a reason to get bad grades. That’s not a reason to cut class. That’s not a reason to give up on your education and drop out of school. No one has written your destiny for you. Your destiny is in your hands. You cannot forget that. That’s what we have to teach all of our children. No excuses. […]

I was raised by a single mom. I didn’t come from a lot of wealth. I got into my share of trouble as a child. My life could have easily taken a turn for the worse. When I drive through Harlem or I drive through the South Side of Chicago and I see young men on the corners, I say, there but for the grace of God go I. They’re no less gifted than me. They’re no less talented than me. But I had some breaks. […]

NAACP, it will not be easy. It will take time. Doubts may rise, and hopes may recede. But if John Lewis could brave billy clubs to cross a bridge, then I know young people today can do their part to lift up our community. If Emmett Till’s uncle, Mose Wright, could summon the courage to testify against the men who killed his nephew, I know we can be better fathers and better brothers and better mothers and sisters in our own families. If three civil rights workers in Mississippi — black, white, Christian and Jew, city-born and country-bred — could lay down their lives in freedom’s cause, I know we can come together to face down the challenges of our own time. We can fix our schools. We can heal our sick. We can rescue our youth from violence and despair.

And 100 years from now, on the 200th anniversary of the NAACP, let it be said that this generation did its part; that we, too, ran the race; that full of faith that our dark past has taught us, full of the hope that the present has brought us, we faced, in our lives and all across this nation, the rising sun of a new day begun.

Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama speaking at the NAACP’s hundredth anniversary celebrations last week.

For more on the NAACP, its history and future, I’m joined now by two guests. Julian Bond, leading civil rights activist, longtime chair of the board of the NAACP since 1998, he also helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, known as SNCC, was the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center, was a state legislator in Georgia for over two decades. Julian Bond joins us now from Washington, DC.

And on the line from Martha’s Vineyard, where the Obamas will soon be vacationing, we’re joined by historian Patricia Sullivan, teaches at University of South Carolina, is a fellow at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard University. Her latest book, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement, where she traces the development of the NAACP from its founding in 1909 as a largely elite organization dominated by white reformers to a mass-black-membership organization synonymous with the struggle for freedom.

We’re going to begin with Julian Bond in Washington. Your response to President Obama’s speech, which I didn’t think got nearly the kind of attention that this speech, perhaps the fieriest of his presidency, should have?

JULIAN BOND: No, not at all. It was a little disappointing. But I’ll tell you, for the people who were there in the room, it was electric. We were just, first of all, overjoyed to see him. He promised us a year ago that he would help us celebrate our centennial at this year’s convention. And it was just a magic moment for all of us. It was a wonderful speech. It contained some elements that we had heard him say before. But I don’t think I’d ever seen this level of passion in President Obama. And so, it was just a great occasion.

AMY GOODMAN: Is it true that Mayor Bloomberg of New York had offered Yankee Stadium, but the White House had turned it down, for the speech?

JULIAN BOND: I think it’s true. We had wanted the President to come in the morning on Thursday, rather than the evening, and were searching around for a larger place than the Hilton Hotel ballroom, which only seats 1,900 people. And we had 6,000 delegates there. We wanted to find a place where all of our people could go and see him, as well as others, New Yorkers, who wanted to come. And the mayor put forward Yankee Stadium, and the Obama White House said, no, that wouldn’t do. We tried for the Armory in Harlem, which seats, I think, 9,000 people. And for various reasons, that wouldn’t do. And so, we settled on that ballroom in — at the Hilton, and it was as tightly packed as I — I’ve been to a lot of banquets; I’ve never been to a banquet that was as hard to move around in as that one.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let me ask, do you agree with what Clarence Page said, the columnist for the Chicago Tribune, who on one of the talk shows, on Chris Matthews Show on NBC yesterday, said that President Obama — it was actually President Obama who didn’t want to do something like Yankee Stadium, didn’t want his biggest address since the inauguration to be to the African American community?

JULIAN BOND: I don’t know whether or not that’s true or not. I had the feeling that the Obama people thought it would be too grandiose, that locale, too big, too large, too reminiscent — or might summon up the kind of criticism he got from his speeches overseas when he was running for president. But for whatever reason, we just could not do it and had to settle on what you heard and saw.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let’s talk about the history of the NAACP. I saw you on Thursday, or Wednesday, before the big event, and you were actually recommending a book by Patricia Sullivan, our other guest today, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement. Of course, the NAACP has also put out their own hundred — Celebrating a Century of 100 Years in Pictures: NAACP.

But, Patricia Sullivan, can you really just lay out the history for us of this organization that was founded in 1909? Begin with who founded it.

PATRICIA SULLIVAN: Well, it was, you know, founded by — initially, the spark came from a handful of white progressive reformists in New York who were responding to a race riot in Illinois, in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908, and seeing the patterns of Southern racism spreading northward, and were alarmed by that. And various people had been involved in ways of trying to address this issue, but they finally decided to meet and come together and immediately contacted W.E.B. Du Bois, who was in on the planning from the beginning.

And they came together in New York a hundred years ago, in 1909, a remarkable gathering of several hundred people, black and white, just to begin to address the problem of race throughout the country, the Southern caste system and also this spread of racial discrimination and segregation northward. And, you know, it was — and that’s what — they were a diverse group of people, but they were joined in this commitment. And the organization kind of evolved in response to the concern, and it was built, you know, as they went forward. I mean, they were very improvisational and open to building something that could begin to push back against this trend and address this deep problem in our history.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about the critical junctures of the NAACP as it moved forward from 1909, the issues that it took on.

PATRICIA SULLIVAN: Well, I think, you know, it’s so huge. But I think one of the very interesting things, as I think you pointed out, you know, a group of — and I mentioned, a group of white reformists were sort of the spark plugs, and initially it was dominated by a group of people in New York, but by the World War I, it had developed into a sort of mass-black-membership-based organization.

And one of the triggers here was, when Woodrow Wilson began to expand segregation in Washington in 1913 after coming in, they organized a national protest and really put themselves on the map as a national organization and really attracted tremendous support from black communities around the country and moved on from there. And I think, as you map their history, one of the very interesting things is, when we look back to the last century, you know, the fall of segregation in the South is one of the major moments in American history. And it builds on these decades of struggle that the NAACP really orchestrated in the South. At the same time, they’re responding to the spread of racial discrimination northward, which increases as black migration to Northern cities increases. And this is a — becomes a tougher issue, because it’s more elusive. It’s very clear what’s happening, but how to gain traction in pushing that back? And so, they’re fighting on these very fronts.

And then they’re also — after the Wilson incident with Wilson’s segregationist policy, they established a lobbying base in Washington that remains and becomes the engine for the civil rights legislation that finally comes to the fore in the ’50s and ’60s. So it’s a multi-front struggle. And we tend to just kind of think of the South, and we have this neat sense of, you know, mass protest, collapse of Jim Crow, great victory. But what this history shows us, exposes, is how — you know, the deep racial fault lines in American society and the ongoing challenges that we face.

I think one of the interesting themes in the book is the fight against segregated housing. The NAACP’s first major Supreme Court victory in 1917 overturned these residential ordinances that were enacted by a number of cities, just very specifically dividing neighborhoods up by race. Then you have the emergency restrictive covenants as another tool, and it takes thirty years to overturn those in 1948. And racial segregation in housing continues to grow through a variety of ways, and it’s supported by urban redevelopment, you know, government-funded programs. The NAACP is continually trying to find the ways to push this back. And the difficulties of doing that — you know, and that impacts all areas of life — education, jobs. Thurgood Marshall said, you know, housing discrimination is one of the greatest evils we face. And the kind of — the resilience of this problem or the difficulties in getting the support to turn it back provides a foundation, really, the problems that remain.

AMY GOODMAN: Patricia Sullivan, I want to thank you for being with us, teaching history at University of South Carolina, a fellow at W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard. Latest book, Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement. Longtime NAACP board chair, Julian Bond, will stay with us. This is Democracy Now! We’re back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama gave a brief overview of the NAACP’s history at his speech on Thursday night and thanked the NAACP and the generation of African American activists and civil rights leaders before him who paved the way for his own victory at the polls.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Long before the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act and Brown v. Board of Education, back to an America just a generation past slavery, it was a time when Jim Crow was a way of life, when lynchings were all too common, when race riots were shaking cities across a segregated land. It was in this America where an Atlanta scholar named W.E.B. Du Bois, a man of towering intellect and a fierce passion for justice, sparked what became known as the Niagara movement, where reformers united, not by color, but by cause; where an association was born that would, as its charter says, promote equality and eradicate prejudice among citizens of the United States.

From the beginning, these founders understood how change would come, just as King and all the civil rights giants did later. They understood that unjust laws needed to be overturned, that legislation needed to be passed, and that presidents needed to be pressured into action. They knew that the stain of slavery and the sin of segregation had to be lifted in the courtroom and in the legislature and in the hearts and minds of Americans. They also knew that here in America change would have to come from the people. […]

And because ordinary people did such extraordinary things, because they made the civil rights movement their own, even though there may not be a plaque or their names might not be in the history books, because of their efforts, I made a little trip to Springfield, Illinois, a couple of years ago, where Lincoln once lived and race riots once raged, and began the journey that has led me to be here tonight as the forty-fourth President of the United States of America. […]

Because of them, I stand here tonight, on the shoulders of giants. And I’m here to say thank you to those pioneers and thank you to the NAACP.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama on the final night of the NAACP’s hundredth anniversary convention held here in New York. Julian Bond still with us, leading civil rights activist, longtime chair of the board of the NAACP.

Julian Bond, you, yourself, have lived the history, for many decades, of the NAACP, the kinds of issues it fought for, as you helped to found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, you were its spokesperson, a state legislator. Talk about the significance of the NAACP and where it’s going today.

JULIAN BOND: Well, I joined the NAACP when I was in college at Morehouse College in Atlanta, and was sporadically active with it for a number of years after that. And then, after the collapse of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, I became active again in Atlanta, became president of the Atlanta branch, eventually was elected to the NAACP board of directors, and eleven years ago was elected the NAACP chairman. And I’ll be stepping down from that in February of next year.

AMY GOODMAN: One quick question.

JULIAN BOND: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: Were you a student of Dr. King, actually in his class?

JULIAN BOND: Yes, I’m actually one of the few people, six people in the whole world, who honestly can say, “I was a student of Martin Luther King,” as he taught one time, one class at Morehouse College. I believe there were six Morehouse College students — Morehouse is all-male — two Spelman College students, all female. So there were eight of us — six or eight of us in the class, and we’re the only people who can say, “I was a student of Dr. King.” So, yes, I was.

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you remember of that class?

JULIAN BOND: I remember that it was a philosophy class that he co-taught with the man who taught him philosophy when he was a student at Morehouse College. And I remember that, actually, we didn’t talk about philosophy much, but he reminisced about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was then just a few years earlier. He talked about the civil rights movement.

And, you know, I’m so mad at myself, and I think all the rest of us, because to us this was not as extraordinary as it may sound today, that this was just a conversation between teacher and students, and the idea of writing it down, the idea of recording it, never entered any of our minds. And I’ve asked my colleagues, my fellow students who were in the class with me, what notes they took, what they remember, and none of us did that. But luckily, one of my colleagues, Reverend Amos Brown, who’s now pastor of a church in San Francisco and on the NAACP board, he has gotten copies of Dr. King’s notes, the notes he used in that class. And I have my own copy of those. And so, I get some idea of what he hoped to talk about in the class, but almost never did.

AMY GOODMAN: When I heard you speaking the other night, you were talking about the conditions, even of lawyers, taking on cases in court, who, because they were black, because they were African American, when they went outside the courtroom, were still segregated. Talk about that experience.

JULIAN BOND: This was a story told to me by Vernon Jordan, who at one time had been Georgia field secretary of the NAACP and was a lawyer, was a new, young lawyer practicing law with two older veteran lawyers, defending a black man of murder charges in a small Georgia town, so segregated that there was no place they could eat. They had to eat in their car.

And Vernon told me that one day during court he heard a noise in the gallery, where the black people had to sit, and he looked up, and a man was sort of beckoning to him. And during a break in the court, the man talked to Vernon and said, “Listen, don’t eat in your car anymore. This time when you break for lunch, drive out of town five miles, turn left, go along here a little ways, and you’ll see a big tree. Stop there.”

So they got in their car, they drove out following this route, and there is a car — there is a picnic table just overflowing with food, about twenty people standing around. And one of the people said to him, “We can’t join the NAACP. The white people here are too tough, too bad. But we can feed the NAACP.”

AMY GOODMAN: Your thoughts on the — one of the many controversies going on today, swimming pool in Philadelphia that didn’t want black children swimming there, this controversy brewing as the NAACP is celebrating a hundred years?

JULIAN BOND: It’s brewing not only as the NAACP is celebrating its hundred years, but as people saying, “Why do we need this organization? Why do we need the NAA — why do we need somebody fighting racial discrimination? Barack Obama is president, and so all discrimination has just disappeared and vanished.”

But our new CEO, thirty-six-year-old Ben Jealous, said, “We’ve come to a point where the President of the United States is black and can walk through the front door of his airplane, but his children can’t swim at a pool in Philadelphia.” And so, if that doesn’t show you why we need the NAACP, I don’t know what would.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what you’re taking on right now, what the NAACP is doing at a hundred.

JULIAN BOND: Well, we — you know, when I heard Obama talking in the bit you played just a moment ago, it’s so odd how he summoned up what we used to do as —- and it’s what we do right now: we fight racial discrimination. I’m constantly asked, “What new thing is the NAACP doing?” because Americans like new things, you know. They want you to do something new every year. We do the same thing. We do it in new years. We fight racial discrimination. We engage in coalition, in litigation, in agitation. That’s what we do. We do it every day all across the country, in small towns and big cities. And we run into incidents like this Philadelphia thing.

But where the incidents don’t occur, we’re working on Capitol Hill, we’re arguing with Congress members, urging them to vote for initiatives that we support and to vote against those we don’t. We engage in critiques of larger institutions and society, ranging from the movie industry, which we were critiquing almost a hundred years ago when The Birth of the Nation [sic] emerged and you saw these awful depictions of black people and awful distortions of actual history, to big corporations. We rate them every year. We issue a report card for them. The list of things we do is too long for the time you’ve got for this show. But we do a great deal -—

AMY GOODMAN: The issue of police brutality that you are —-

JULIAN BOND: Police brutality -—

AMY GOODMAN: — and what you’re doing right now.

JULIAN BOND: Well, our new CEO Ben Jealous has hit upon a wonderful plan, and he’s urging all of our members and all of our supporters who may not be members to use their cell phones as others have used them successfully, to record instances of bias and discrimination with their cell phone cameras. Send them to us. We’ll send you a report form. You’ll tell us where this happened, who was involved, as much as you know about it, and we’ll put it on the web. And we’ll have a record of some egregious example of bigotry or racial discrimination.

I don’t know how many of your listeners or hearers may have seen the or heard the video of the policeman in some town in Philadelphia, drunken policeman at a bar, just railing about how he had beaten up some black person for no reason, apparently. And luckily, somebody in the bar had a camera and recorded him, and now we have a record of this.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to ask you about Troy Anthony Davis. Ben Jealous, the new thirty-six-year-old head of the NAACP, was introduced by a young man who just turned fifteen in June, Anthony Davis-Correia. Davis — well, that’s for Troy Davis, his uncle. Troy Anthony Davis is on death row now in Georgia. And the NAACP has taken on his case. In fact, if Sonia Sotomayor becomes the next Supreme Court justice —-

JULIAN BOND: And she will.

AMY GOODMAN: —- she will be sitting on the court when they rule on Troy Anthony Davis’s case. It’s a case where he’s raising the issue of innocence.

JULIAN BOND: Absolutely. Of the nine witnesses who testified against him at his original trial, seven of them have recanted their testimony. And among them are people who said, “No, it wasn’t him. It was one of the other witnesses who testified to put him in jail, where he sits now.” So there are serious questions raised about his guilt. And a peculiar coalition of people, not just the NAACP, but conservative former Congressman Bob Barr from Georgia, a former Attorney General of the United States — I mean, there’s a large body of respectable people who say this —-

AMY GOODMAN: President Jimmy Carter.

JULIAN BOND: President Jimmy Carter -— who say this is just an enormous miscarriage of justice. And to send this man to the electric chair, where all this doubt has been raised about him, is nothing more than state-sponsored murder. But our CEO Ben Jealous formerly worked for — jeez, the — in anti-death penalty work and dealt with hundreds and hundreds of these cases, and he is well equipped to help carry this fight forward, as we carried it forward over past years with other people in similar situations and as we’ll do in the future.

AMY GOODMAN: Eric Holder, the new Attorney General, also addressed the NAACP. Now, the NAACP has just passed a resolution asking him to investigate the case of another man on death row, Mumia Abu-Jamal. What is your stand on that case? What is the NAACP doing?

JULIAN BOND: Well, we’re going to ask Attorney General Holder to look into this, as anyone who’s followed this case for a number of years know that similar doubts have been raised about him as were raised about Troy Davis. And he’s had trouble bringing these doubts before a tribunal that can say, you know, these things are true or they’re not true. And we think he needs that chance. We think he needs that chance before the state of Pennsylvania decides to snuff his life out.

We oppose the death penalty, and particularly so in these cases where innocence seems likely, seems possible. I mean, just think of the notion of killing someone and then finding out later, boy, we made a terrible mistake, I’m so sorry. I mean, that cannot hold. That cannot be done. So we’re trying to, not only with the Mumia case, but other cases, we expect to talk to General Holder and see if he won’t put the force of the US government behind them.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you support Attorney General Holder in what seems to be a split with President Obama over the possibility of investigating the Bush administration, some members of it?

JULIAN BOND: Absolutely. You know, on the one hand, you know, it’s good to say, “Let’s go forward and forget the — what happened in the past.” But we Americans need to know. We want to know who did what, why did they do it, why weren’t we told at the time, how did we get led into this quagmire in Iraq. Many of us have good ideas why, but we need to know. Americans need to know these things. So we support General Holder in this.

AMY GOODMAN: And the criticism some had, young people at the convention, of recruiters being at the NAACP, Julian Bond?

JULIAN BOND: Yes, this, a criticism raised in the past. We have had, generally speaking, a good relationship with the United States military, with all the branches of service. Our local branches have military affairs committees, able to look into questions of discrimination or bigotry if they arise in any branch of the military. But we generally have had a pretty good relationship with the military, almost from the days since Harry Truman integrated the US military and allowed black men and women to serve on an equal level and an equal rank as do white enlisted personnel. So we welcome these recruiters. And, you know, you may have your own just feelings about the American military and the uses to which it is presently —-

AMY GOODMAN: We have five seconds.

JULIAN BOND: —- taken, but we welcome them and are glad to have them.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Bond, thanks so much for being with us, outgoing chair of the NAACP, on its hundredth anniversary. And that does it for our broadcast.

JULIAN BOND: Thank you for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: Thanks so much for coming in.

Media Options