Guests

- Abrahm Lustgartenreporter for investigative news website ProPublica. He has been covering this issue very closely for the past year and has broken a number of stories.

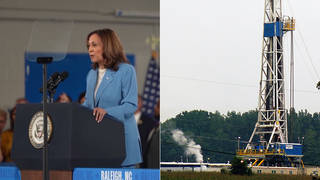

Gas drilling companies such as Halliburton say the gas drilling technique known as hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” is safe, but opponents contend it pollutes groundwater with dangerous substances. Now, new evidence has emerged possibly linking natural gas drilling to groundwater contamination. ProPublica journalist Abrahm Lustgarten reports federal officials in Wyoming have found that at least three water wells contain chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: We turn now to another story about water. New evidence has emerged possibly linking natural gas drilling to groundwater contamination. ProPublica reports federal officials in Wyoming have found that at least three water wells contain chemicals used in the natural gas drilling process of hydraulic fracturing.

The Wyoming study marks the first time the Environmental Protection Agency has undertaken its own water analysis in response to complaints of contamination in drilling areas. Residents in Pavillion, Wyoming, have complained for years that their water wells turned sour and reeked of fuel vapors shortly after drilling took place nearby.

ProPublica reports precise details about the nature and cause of the contamination have been difficult for scientists to collect, in part because the identity of the chemicals used by the gas industry for drilling and fracturing are protected as trade secrets.

AMY GOODMAN: Gas drilling companies, such as Halliburton, say the gas drilling technique known as hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” is safe, but opponents contend it pollutes groundwater with dangerous substances. Here in New York, many politicians and residents have expressed concern that natural gas drilling in upstate and in Pennsylvania could contaminate New York City’s drinking water supplies.

In a moment, we’ll be joined by reporter Abrahm Lustgarten of ProPublica, who has been closely tracking this story. But first we want to play an excerpt from a new documentary called Split Estate by Debra Anderson. The documentary examines the impact the oil and gas drilling boom has had in the Rocky Mountain West. This part deals with Garfield County, Colorado.

NARRATOR: In 2004, some residents in Garfield County began to complain that they were getting sick as a result of the drilling activities in their neighborhoods. A young woman from Silt, Laura Amos, was one of the earliest and loudest voices.

LAURA AMOS: As everyone in this room probably knows, my groundwater has been contaminated with methane, Williams Fork gas. There are a lot of people in this room with contamination and pollution issues. So, who then is responsible to me for that loss of my welfare, if it’s not you, the gas commission?

GAS COMMISSIONER: If a well is drilled next to your residence or near your residence within the legal setbacks, and there’s a perceived or real impact on your property value, we don’t address that.

NARRATOR: In 2001, gas wells were drilled using the fracking technique a mere 500 feet from the Amos home. Underground, the drilling breached their water well, causing their drinking water to fill with grey sediment and fizz like soda pop. The Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission tested the water well and found methane but said it was safe. But they warned the Amoses to keep a window open, so the methane gas wouldn’t build up and cause an explosion in their home. The Amoses stopped drinking the water but continued to bathe in it.

UNIDENTIFIED: A young woman called me from Garfield County and said that she had developed a rare adrenal tumor, that she had had this incident with her well. That was the beginning. I mean, when she called, it just sent chills up and down my spine. She had been breast-feeding her daughter through the period when they were using the water that they were told was safe. She was bathing her baby in the water in their home. They were breathing the stuff that was coming into their house.

NARRATOR: She later found out that a chemical that had been used in the 2001 fracking has been linked to adrenal gland tumors. When she went to EnCana, they denied using it on that well or any other. Months later, the Oil and Gas Commission admitted that it had been used after all.

UNIDENTIFIED: Laura was told her water was safe, and we found out later they never tested it for 2BE. They waited ’til four years after the incident to go back to see if possibly they could find some. That was long gone.

She spoke to other people in her neighborhood. She began to see if anybody else was having the kind of health problems she had. And then others began telling me about people they heard about. And I was just amazed at the numbers of people that were involved. And I thought, this is maybe a serious problem. What is going on over there?

NARRATOR: After years of mounting medical bills, devalued property and diminishing options, Laura agreed to a monetary settlement with EnCana Corporation, the company responsible for her problems. The settlement stipulated she stop telling her story publicly, which is why she was not interviewed for this film. Many family stories like hers will never be told because of company settlements that require silence.

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt from the documentary Split Estate by Debra Anderson. When we come back from break, we’ll be joined by a reporter who has been investigating the issue of fracking around the country and the pollution of the nation’s water supply. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined by Abrahm Lustgarten, covers issues around natural gas drilling for ProPublica. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, Abrahm, tell us first, how does this fracking actually work?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: It’s used to extract oil and gas both, very deep underground, in some cases, 10,000 feet or 13,000 feet underground. And in the current exploration plays, we’re looking at tight sands, or shale, that hold the gas in tiny little bubbles, and it can’t really flow freely. So the oil and gas industry will drill a well, and they’ll pump down millions of gallons of liquid, which is sand and water and then these chemicals that I’ve been looking at. And they’ll pump it down under thousands of pounds of pressure to essentially fracture and break up, obliterate, the rock underneath and let the gas flow back out and come back up to the surface.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And the chemicals that are involved that you say you’ve been investigating?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, it’s very difficult to know exactly what they are. At this point, the industry has released partial lists. They say that they’re mostly complete, but they won’t go on the record and say that it represents every single chemical that they’ve used. In the past, it’s included diesel fuel. That’s been phased out to rely more on methanol. And then there are a number of soaps and surfactants and lubricants and all sorts of things that they use to essentially engineer the viscosity of the fluid. They want it to go down into the hole as a fairly thick substance and then, you know, on command, they want it to release and get out of the way, so the gas can flow right back up past it. And it’s chemicals that does all of that.

JUAN GONZALEZ: So, in essence, the chemicals then — the residuals then flow into whatever groundwater supply may be in the region, right?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, that’s what’s been very difficult to know. Records are not kept about what amount of fluid and chemicals is taken back out of the well, not in any state where drilling is allowed in the United States. There are geologists who are quite concerned about how far these chemicals and these fluids can travel underground. And then there are these numerous correlative instances of contamination across the country. And until now, it’s been very, very difficult to know whether it’s the actual fracturing process that’s caused this contamination or something else. And it’s partially because there’s so much secrecy around the fracturing process itself.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us about the main areas affected in the country.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, it’s almost everywhere you look where there’s drilling. There’s drilling in thirty-one states. Drilling has been happening in Wyoming and Colorado for many years. Probably the most intensive development in the country, at least in the early stages, was there. And that’s where you’ve begun to see quite a bit of problems with the water. And these are largely due to spills sometimes or waste streams that are leaked out into the soil and get into water supplies. And sometimes it’s completely mysterious. The documentary clip showed a woman whose well exploded the same day or within a few days of this intensive pressure being pumped into the ground nearby, which implies some kind of geological connection. There have been problems with water in New Mexico, in Wyoming, in Louisiana, in New York, in Pennsylvania.

AMY GOODMAN: The latest Wyoming EPA study?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: In Pavillion, Wyoming, where some of these earliest complaints originated, the EPA has just earlier this year undertaken, for the first time, a real investigation into what’s happening with the water there. They didn’t go in to investigate the gas industry or hydraulic fracturing, but it is the first time that they’ve actually decided that they would test water in response to complaints about water. And they’ve gone in and tested for the broadest array of pollutants with as much objectivity as they could muster. They’ve looked for pesticides and agricultural influences and any other influence on the water supply.

And EPA folks tell me that they’re quite surprised, but what they found in their preliminary reports — and they’re not finished with this study, but they found a couple substances that seem to be linked to gas drilling, and one of them is a substance called 2-butoxyethanol that is used — not exclusively, but is used — in hydraulic fracturing. And it’s also found in some cleaning supplies and some things we use around the house. But it appears to be, at this point, a strong circumstantial link to hydraulic fracturing.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And what are the main companies that are involved in this drilling?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, the industry works in a funny kind of way, depending on multiple tiers of contractors. So it’s all the big oil companies, whether it’s Chesapeake or Shell or Chevron. And then they rely on service companies to do the hydraulic fracturing itself, and that industry is controlled by three large players: Halliburton is one, BJ Services and Schlumberger, the French giant.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about how the energy industry swayed Congress, and the Safe Drinking [Water] Act, how fracking got exempted?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, this is politically the most controversial point. In the early days of the George W. Bush administration, Dick Cheney’s energy task force identified hydraulic fracturing as a very important part of the natural gas industry and the ability to develop that industry. And within a year or two after that, there was a proposal put forth to exempt the hydraulic fracturing process from the Safe Drinking Water Act, which is the nation’s premier, you know, water protection law.

It’s not clear that, before that, the EPA was enforcing hydraulic fracturing or was looking at it under this act. And in some cases they weren’t, but they clearly had the authority to do so. And this law took away their opportunity to even decide that this was an issue worthy of EPA investigation.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to play an excerpt again from Split Estate. Filmmaker Debra Anderson interviews Weston Wilson, an environmental engineer in the EPA’s Denver office. In 2004, Wilson openly questioned an EPA study that declared fracking “poses little or no threat” to drinking water.

WESTON WILSON: The former chairman, CEO of Halliburton, Dick Cheney, within a few months of coming into office as vice president, he was pressuring the administrator of EPA, Christine Todd Whitman, to exempt hydraulic fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act regulation. From my own point of view as a technician, I just thought it very alarming that EPA technically had described how toxic these materials are, toxic at the point of injection, and still come out with a summary that says they don’t need to be reported or regulated.

And that led me, in the fall of ’04, to object on technical grounds. Then the Inspector General of EPA began an investigation of my complaints. And several months into that, Congress took the report from EPA saying that fracking did not present a risk, along with other information, and exempted hydraulic fracking from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. That leaves you and I, as the American public, in this position: we cannot know what the industry injects in our land. It is exempt from being reported.

AMY GOODMAN: EPA’s Weston Wilson. Your response, Abrahm?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, the EPA did undertake that study in 2004, and it’s been highly criticized by Wes Wilson and numerous other scientists who work very directly with these issues. In Colorado, the EPA essentially undertook a survey at that time. They went and heard some of the complaints from residents that their water was bad. They went and asked state regulatory agencies whether they’d seen contamination, and those regulatory agencies said, “Yeah, for the most part, no, we haven’t.” And the EPA, despite its scientific judgment that there was a potential risk to groundwater supplies, which their report clearly says, then went ahead and very surprisingly concluded that there was no risk to groundwater, unless you read deeper into that report.

And part of my reporting found that throughout that process the EPA was closer than seemed comfortable with the industry. I filed FOIA requests for some documents and found conversations between Halliburton employees and the EPA researchers, essentially asking for an agreement from Halliburton in exchange for more lax enforcement. The EPA, in these documents, appeared to offer that and agree to that. And it doesn’t appear, by any means, to have been either a thorough or a very objective study. And that’s why what’s happening in Wyoming now is so significant, because it’s really a change of course for the EPA on this issue.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And the head of the EPA then was Christie Todd Whitman, wasn’t it?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: It was, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’re going to leave it there, but we will continue to follow your reporting, very important for the health of this country. Abrahm Lustgarten, reporter for the investigative news website ProPublica, has been covering the issue very closely around the country, the issue of fracking.

Media Options