Guests

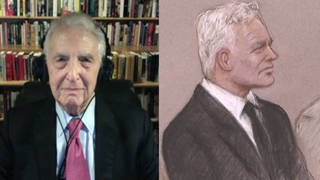

- Ethan McCordIraq war veteran. He was one of three US soldiers who were on the ground during the Apache helicopter assault on twelve civilians in Baghdad in 2007 that was captured in a video released by WikiLeaks.

Iraq war veteran Ethan McCord was one of three US soldiers who were on the ground during the Apache helicopter assault on twelve civilians in Baghdad in 2007 that was captured in a video released by WikiLeaks. McCord is seen on the video carrying one of the wounded children in his arms to get medical help. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Ethan, you’re an Iraq war veteran. We dealt a lot with this case in 2007, the case that WikiLeaks revealed with the videotape that was taken by the US military in the Apache helicopter, where your unit opened fire on Iraqi civilians, the helicopter attack that killed twelve people and wounded two children. The dead included two employees of the Reuters news agency, photographer Namir Noor-Eldeen and driver Saeed Chmagh. The WikiLeaks.org posted the footage from the helicopter. This is the moment the US forces first opened fire.

US SOLDIER 1: Have individuals with weapons.

US SOLDIER 2: You’re clear.

US SOLDIER 1: Alright, firing.

US SOLDIER 3: Let me know when you’ve got them.

US SOLDIER 2: Let’s shoot. Light ’em all up.

US SOLDIER 1: Come on, fire!

US SOLDIER 2: Keep shootin’. Keep shootin’. Keep shootin’. Keep shootin’.

US SOLDIER 4: Hotel, Bushmaster two-six, Bushmaster two-six, we need to move, time now!

US SOLDIER 2: Alright, we just engaged all eight individuals.

AMY GOODMAN: Ethan McCord, you were one of three US soldiers who were on the ground after that attack. You pulled the two children out of the minivan that was fired on to help get them to the hospital. Can you talk about what happened and how it affected you?

ETHAN McCORD: Yes, I did pull the children out of the van that day and didn’t find out that they were denied to go to Rustamiyah for healthcare until afterwards. Later on that evening, after the incident, when I was back at the FOB and I washing the blood of the children off of my uniforms, you know, my mind was a mess. I was very emotional, couldn’t really deal with what I had seen and, more importantly, was more upset with what I was a part of. So I went to my staff sergeant and asked to see mental health, so that I can talk about my feelings and what I was feeling. And I was denied to go to mental health. They told me I needed to suck it up and that there would be repercussions if I was to go see mental health, and I would be charged with malingering. And I was rather shocked that just by me needing to speak to somebody about what was going on and what I was feeling could constitute a crime in the Army. So, like the good soldier, you know, and not wanting to be charged with malingering, I did in fact push everything down as much as I could and —-

AMY GOODMAN: Ethan, can you tell us -—

ETHAN McCORD: — tried to move on.

AMY GOODMAN: So, the Apache helicopter attacks the men on the ground, and you see — and people can see it at our website, democracynow.org — I mean, when one of the Reuters employees doesn’t quite die, how he’s crawling away, and they strike him again, until he dies. You then are on the ground. They blow up this van, but you save the children. Did you say that they denied you taking them to the US military hospital?

ETHAN McCORD: Well, I placed the boy into the Bradley armored vehicle, and the Bradley was not a part of our unit, and neither were the Apaches. They were just attached to us that day. When I placed the boy into the Bradley armored vehicle, I was yelled at by my platoon leader for worrying about children instead of worrying about other — finding other people to kill. I was not aware that they were denied to medical care at Rustamiyah, where we — where our FOB was. Actually, I wasn’t aware of that until the video was released. In fact, I didn’t even know there was a video.

AMY GOODMAN: Because it was in the Apache helicopter?

ETHAN McCORD: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what happened to you then. Eventually, you did come home, after what? Five months?

ETHAN McCORD: Yeah, I came home in November. I was wounded in Iraq. I came home and was still trying to seek mental health counseling, which was — the mental health in Fort Riley, Kansas, was just overwhelmed. You had to wait at least six weeks to be seen by somebody in mental health. I had to — my command there didn’t know that I was trying to sneak down to mental health to be seen. And in fact, I had a talk to someone who was a civilian psychologist first, just to get some of the emotions out. While I was waiting to be seen by mental health, I started self-medicating by drinking a lot. And when I tried to commit suicide through alcohol, I was then taken to a civilian mental health hospital where I started to receive help before the Army even helped me.

AMY GOODMAN: Your wife tried to get you into a hospital?

ETHAN McCORD: Right. She kind of like tricked me into going to the hospital and — in fact, I went to the Irwin Army hospital, where they had a psychologist who was on duty. He didn’t really talk to me or anything. They called my command, and one of the staff sergeants who were there came down to the hospital, and instead of — just degraded me while I was in there, said that I was nothing, I was nobody, because I was doing this. And so, you know, I had to listen to that, as well. And in Fort Riley, they didn’t have a military mental health hospital there, so they sent me to a civilian mental health hospital, where they began to prescribe me multiple medications, like Geodon and Depakote at the same time, which are both severe antipsychotics, which is just a few of my thirteen medications that they put me on.

AMY GOODMAN: Brock, you were brandishing — I mean, you didn’t — your marriage didn’t survive. You got divorced. But you were walking around the house with a knife? I mean, sorry, Ethan, Ethan McCord.

ETHAN McCORD: Yes, I was. Yeah, I don’t remember the incident, but according to my ex-wife, yes, I was.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, what does this data mean to you, Ethan, this day that you join with other vets and soldiers in Washington, DC? How many other soldiers do you know like you? And how many others do you know like you who are being sent back to Afghanistan?

ETHAN McCORD: There’s — I know many soldiers who suffered from PTSD and TBI and who are being ignored. This problem — this systematic problem is being ignored. And they’re being redeployed. The unit that I was with, they just got back from Iraq a few months ago. You know, one of the soldiers who was there, they kicked him out, knowing he had PTSD. They kicked me out, knowing I had PTSD, TBI and had metal rods and pins in my back. And they kicked me out on what’s called a Chapter 517, which states that all of my conditions were pre-existing. They’ve done this to over 250,000 soldiers. And it’s time to stop. It’s said between — twenty percent, at the minimum, of troops are suffering from some sort of trauma, whether it be TBI, PTSD or military sexual trauma. That’s an extreme amount of soldiers who are suffering. And they’re being denied their basic human rights to heal. And we’re trying to put a stop to that. It needs to end now. And we need to — we need to stop the redeployment of these troops.

AMY GOODMAN: Time magazine has learned Army troops are seeking mental health more than 100,000 times a month, the figure reflecting a growth of more than 75 percent from the final months of 2006 to the end of 2009, according to Army data.

Media Options