Related

Guests

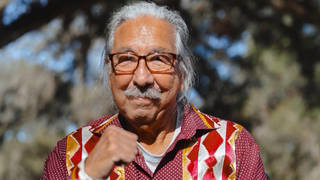

- Ezequiel Adamovskyhistorian and activist who teaches at the University of Buenos Aires.

As we broadcast from Buenos Aires, we look at the economic rebellion of Argentina that took place after the government defaulted on $95 billion in foreign loans in 2001. The next two years saw record protests and social upheavals that changed the country’s political landscape. Today, Argentina’s current president Cristina Kirchner is in South Korea taking part in the G20 summit. We speak with Ezequiel Adamovsky, a historian and activist who teaches at the University of Buenos Aires. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We are on the road in Buenos Aires, Argentina. When we flew in yesterday, our first stop here in the Argentine capital was the Plaza de Mayo where mothers of the disappeared continue to march every Thursday afternoon holding the pictures of their children and grandchildren who were disappeared. Thirty thousand people were disappeared during Argentina’s military dictatorship, which ended in 1983.

Well, two weeks ago, tens of thousands of people gathered here in Buenos Aires to mourn the passing of the former Argentine president Néstor Kirchner. He headed Argentina from 2003 to 2007 as it struggled to recover from a crippling financial meltdown. His wife, Cristina Kirchner, is the current president of Argentina. Today, she’s in South Korea taking part in the G20 summit — this, as a group of financiers took out an ad in the Wall Street Journal demanding Argentina be thrown out of the G20.

See, in 2001, Argentina defaulted on $95 billion in foreign loans. The next two years saw record protests and social upheavals, and unemployement was at an all-time high. Soon after taking office in May 2003, Néstor Kirchner told the International Monetary Fund Argentina would only give its creditors 35 cents back for every dollar they were owed. The IMF restructured Argentina’s debt.

Néstor Kirchner is also credited with reforming the judiciary and armed forces and paving the way for dozens of trials involving people accused of torture and other abuses during the military dictatorship. We’ll talk more about these trials later in the show today, but first we go to some analysis of the economic transformations in Argentina since the massive street protests of 2001.

Joining me here in Buenos Aires is Ezequiel Adamovsky. He’s a historian at the University of Buenos Aires. He has been involved in the student movement in the neighbourhood assemblies that emerged in Buenos Aires after the protests in December 2001.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Professor Adamovsky, Ezequiel. Talk about what happened. For viewers and listeners who are watching and listening all over the world right now, put Argentina in a political and geopolitical context.

EZEQUIEL ADAMOVSKY: I think the most important thing to take into account was that Argentina, during the 1990s, was the most extreme experiment in neoliberal transformation. We had the most radical program of reforms at that time, which ended up in massive unemployment, impoverishment of more than half of the population of the country, and in 2001, finally, the collapse of the whole economic system. At the same time, we had a crisis of credibility in the political system. Since every single political party was proposing the same types of measures, neoliberal measures, population lost confidence in all politicians at the same time. So we — in 2001, we had the vast majority of the population rejecting neoliberal measures and not having any political alternative in the established political parties as to how to continue ruling this country.

So that was the moment in which the rebellion happened. And the rebellion was basically, at the same time, a rejection of austerity measures and also a rejection of the political system. The main slogan of the rebellion was “They must all go,” meaning that all politicians should leave the political scene. So, up until this, there was no political alternative then. But the most interesting aspect of the rebellion was that precisely at that moment, large social movements started to experiment new forms of political representation, new political slogans and programs. And some of the measures that you just mentioned, which Néstor Kirchner took after 2003, were actually the measures that the rebellion itself was proposing. For example, the renewal of the Supreme Court was one of the demands of this vast social movement in 2001.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean, the renewal of the Supreme Court?

EZEQUIEL ADAMOVSKY: Well, one — Néstor Kirchner is credited with changing the utterly corrupt Supreme Court that we had in the ’90s with a new one that we have now with more or less respectable judges. That was one of the main demands of the rebellion in 2001.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you participate? And, I mean, the significance, for people to understand these protests in 2001, the uprising in the streets? How many people were in the streets? I mean, you had very much, I mean, the middle class out, as well as the students, smashing the windows of banks.

EZEQUIEL ADAMOVSKY: That is right. It’s impossible to say how many people participated. But in the rebellion of December 2001, it was millions of people in the streets, in Buenos Aires but also in most of the cities throughout the country. And it was the middle class, but also the lower classes in the outskirts of cities, as well. So it was a very special moment of solidarity between lower and middle classes against these neoliberal measures.

AMY GOODMAN: You have written several books. One of them is called Anti-Capitalism for Beginners: The New Generation of Emancipatory Movements. What do you mean?

EZEQUIEL ADAMOVSKY: Well, that book was about trying to communicate, wider audiences, the ideas that social movements in Argentina were debating at that time. So we had the sense that we were debating all sorts of new ideas, but we didn’t have channels to spread all these ideas to larger audiences. So, the basic idea was that we were experiencing then the birth of a new sort of — a new formula of anti-capitalist movements, different from anti-capitalists of the past, at the same time being inheritors of that tradition, but also experimenting with new ideas and trying to reach better outcomes than the movements of the past.

AMY GOODMAN: Ezequiel Adamovsky, it’s interesting, your latest book is called The History of the Middle Class, and there’s a lot of discussion of the middle class in the United States, because of the economic pressure and the economic meltdown in the United States while the middle class lasts there. But why did you write a book on the history of the middle class? How has it changed here in Argentina?

EZEQUIEL ADAMOVSKY: Well, I think I wrote that book without knowing it, perhaps, because I believe that there’s no deep social change possible without solidarity between the lower class and at least part of the middle class. And since I believe that the capitalist political system is about separating those two classes in different fields, I think that the most important challenge that we have, politically speaking, is to reunite part of the middle class with lower class in new kind of bonds and links of solidarity.

In Argentina, the middle class suffered a process of impoverishment throughout the ’90s. There was a new phenomenon called the “new poor,” meaning people who used to be middle class but they were now poor people. And that process, funnily enough, it reapproached, from the identity viewpoint, the identity of the middle class, impoverished middle class, and the lower class. And historically speaking, in Argentina, there was a big gap between those two, the middle class usually rejecting any contact with poor people. But that slightly changed in the ’90s. And in part, the 2001 rebellion was possibly due to that.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the remarkable fallouts from the economic collapse of 2001 was that workers in Argentina began taking over factories abandoned by their owners. Latin America’s most prosperous middle class suddenly found itself in a ghost town of abandoned factories and mass unemployment. What happened next is the story of a documentary by well-known author Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis called The Take. In suburban Buenos Aires, 30 unemployed auto parts workers walked into an idle factory, rolled out sleeping mats, and refused to leave. All they wanted was to restart the silent machines.

AVI LEWIS: Zanon Ceramics. After two years under worker control, it’s the granddaddy of this new movement. Today, the factory is in production with 300 workers. Decisions are made in assemblies: one worker, one vote. Everyone gets exactly the same salary.

NAOMI KLEIN: It wasn’t always like this. A couple of years ago, the owner claimed that the plant was no longer profitable, that it had to be shut down. The workers refused to accept that fate. They argued that the company owed so much to the community in debts and public subsidies that it now belonged to everyone. In the Menem years, the Zanon factory had received millions in corporate welfare, and the owners still ran up huge debts. Now that his workers have restarted the machines, he’s back.

Are you going to get your factory back?

LUIS ZANON: [translated] I’m going to get it back.

NAOMI KLEIN: How are you going to do it?

LUIS ZANON: [translated] The government will give it back to me. The government will give it back to me.

AVI LEWIS: That means the workers can never rest. They keep a 24-hour guard at the factory, and everyone is equipped with a slingshot, in case the police show up.

NAOMI KLEIN: Their struggle against authority has even won them fans in one of Argentina’s biggest rock bands. Bersuit is in town, and the band is dedicating its show to the workers of Zanon.

MEMBER OF BERSUIT: [translated] What the guys in Zanon did, fighting against the police with just marbles, like when we were kids, with slingshots against real weapons, they took over the factory.

AVI LEWIS: But as we discovered walking down Main Street, Zanon’s real weapon is the support of the community.

NAOMI KLEIN: What do you think of the Zanon plant under worker control?

MAN AT COUNTER: [translated] That it works better than under the former owners, because at least people are working. The tiles are cheaper, and the future is brighter than it was under the owners. All they did was get subsidies from the state, nothing else, and they kept the money for themselves.

WOMAN AT COUNTER: [translated] All I know is that the community supports them 100 percent, because they’re not stealing, they’re not killing anyone. On the contrary, they’re working to feed their families.

BARBER: [translated] There are many companies that should be in the hands of the workers. But it seems that this is not politically convenient. That’s the real problem.

CROWD: [translated] And now that we are in production, Mr. Zanon, you can kiss our asses!

NAOMI KLEIN: What do you think of this slogan of the workers, which is “_Zanon es del pueblo_,” “Zanon is of the people”?

LUIS ZANON: [translated] What can I say? It’s not true. It’s not of the people. The investment was mine, all the work was mine. I put in everything. It can’t be “of the people.”

AVI LEWIS: You’re standing in front of $90 million worth of factory, which you and your companeros have taken over for your own benefit. We have a word for that. It’s called stealing.

RAUL GODOY: [translated] There’s another word: “expropriation.” And that’s what we’re going for.

NAOMI KLEIN: The Zanon workers have gathered thousands of signatures supporting their demand for definitive expropriation. They donate tiles to local hospitals and schools.

AVI LEWIS: And Zanon’s community building has paid off. Since the workers’ takeover, they have fought off six separate eviction orders. Each time, thousands of supporters have flocked to the factory, set up defenses, and been ready to put their bodies between the machines and the police. Each time, the judges’ trustees have retreated, leaving the factory under worker control. For now, Zanon really is the property of the people.

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt of Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein’s The Take about the occupied factories. Professor Ezequiel Adamovsky, as we wrap up, the significance of this recovered factory movement and also how you’d place it in the context of what happened before, in the last decades, the dictatorship that caused the disappearance of, what, roughly 30,000 Argentines?

EZEQUIEL ADAMOVSKY: Well, the dictatorship that we had after 1976 implemented also for the first time a neoliberal program in Argentina. And the consequence of that was the drastic reduction of the industrial sector in Argentinian economy. Throughout the '90s, we also had a big loss of thousands of firms throughout the country. And it was interesting that the occupied factories movement started by a measure of the workers to defend their jobs. But soon after that, they moved into trying to prove that actually factories could be run by the workers themselves, actually better than the businessmen. And in 2002 and 2003, there were already over 200 occupied factories being run by the workers in Argentina, including the biggest — for example, the biggest tile factory in the whole of Latin America, which is still running under workers' control. Most of those companies are today still running successfully. So it was very inspiring for — although there were not very many companies. It was only, one could say, only 200 cases. But 200 cases were of a great significance to prove that there were alternatives against neoliberalism, and those alternatives were being tested and implemented by the people themselves and not by politicians or elites.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Ezequiel Adamovsky, I want to thank you very much for being with us. He is a professor at the University of Buenos Aires. Among his books, Anti-Capitalism, and his most recent book, The History of the Middle Class. Professor Adamovsky teaches history at the University of Buenos Aires. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. When we come back, we’ll talk about what happened during the dictatorship with the dictatorship’s survivors. Stay with us.

Media Options