Guests

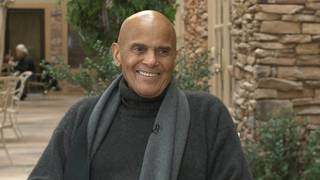

- Stanley Nelsonaward-winning filmmaker and director of The Freedom Riders. His other films include The Murder of Emmett Till and Wounded Knee.

- Bernard Lafayetteparticipated in the Nashville-New Orleans Freedom Ride in 1961. Dr. Bernard Lafayette is Distinguished Professor in Religion, Conflict and Peacebuilding and senior scholar-in-residence at Emory University.

- Jim Zwergparticipated in the Nashville-New Orleans Freedom Ride in 1961. He was severely beaten by a mob in Montgomery, Alabama.

The International Civil Rights Center and Museum opens today in Greensboro, North Carolina at the site of the historic 1960 Woolworth’s sit-in. To mark the start of Black History Month, we turn to the story of another group of young people who were inspired by the success of the nonviolent strategy of the Greensboro sit-in. Starting in May of 1961, mixed groups of black and white students began taking interstate buses into the Deep South, risking their lives to challenge segregation. They called themselves the Freedom Riders. White mobs responded with violence. One bus was set on fire with the Freedom Riders. Numerous Freedom Riders were brutally beaten and hospitalized. We speak to Stanley Nelson, the director of the new documentary The Freedom Riders that premiered at Sundance last week. We also speak to two of the original Freedom Riders, Bernard Lafayette and Jim Zwerg. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN:

Fifty years ago today, four seventeen-year-old freshmen at the all-black Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina sat down at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina and ordered some food. They were refused because they were black. But they continued to sit at the counter and returned the next day and the day after that. Their protest sparked a sit-in movement across the segregated South and Woolworth’s was desegregated in July of 1960.

Well, today, as the International Civil Rights Center and Museum opens at the old Woolworth’s building in Greensboro, we turn to the story of another group of young people who were inspired by the success of the nonviolent strategy of the Woolworth’s sit-in. Starting in May of 1961, mixed groups of black and white students began taking interstate buses into the Deep South, risking their lives to challenge segregation. They called themselves the Freedom Riders.

In December of 1960, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional segregation in public transportation and interstate bus and rail stations. But despite the ruling, Jim Crow travel laws remained in force throughout the South. Six months later, a dozen black and white students decided to challenge the local laws of the Deep South and test the commitment of the Kennedy administration to civil rights. On May 4th, 1961, the group took two public buses from Washington, DC and intended to arrive in New Orleans two weeks later.

A new documentary by Stanley Nelson tells the story of what happened to these brave students over the next few days and weeks and how they inspired hundreds of others to join the Freedom Rides and eventually succeed in desegregating public transportation. The documentary premiered at the Sundance Film Festival last week. It’s called The Freedom Riders and will air on PBS’s American Experience next year.

I interviewed two of the Freedom Riders featured in the film: Bernard Lafayette and Jim Zwerg. Jim Zwerg was beaten unconscious during the Rides. But first, I spoke to the director of the documentary, Stanley Nelson.

AMY GOODMAN: Congratulations on this remarkable film, Stanley Nelson.

STANLEY NELSON:

Thank you so much.

AMY GOODMAN:

Talk about the origins of this. Why did you choose the Freedom Riders?

STANLEY NELSON:

Well, I think the Freedom Riders is a great, great story. It’s kind of the story of the beginnings of the civil rights movement. It’s a story that so many people really don’t know, and it will be the fiftieth anniversary of the Freedom Rides in 2011. So we wanted to get the film started and make sure that we got it, and got it out, and got it done in time for that.

AMY GOODMAN:

Tell me about the Freedom Riders and how you pieced this together — I mean, it is the most dramatic telling of this story — and its significance in history.

STANLEY NELSON:

Well, you know, let me explain in just a real quick way — in a quick way what the Freedom Riders were. In 1961, twelve people, both black and white, decided that they would test the segregation laws of the South by simply getting on buses, Greyhound buses and Trailways buses, and going down south. And the white and black people would sit together at the front of the bus. They would eat together in the restaurants in the bus stations. The white people would use the colored-only restrooms, and the black people would use the white-only restrooms. And they would just see what would happen to them. And they had no police protection, no army protection, very little press when they started out, and they had no idea that it would really turn into this mass movement.

AMY GOODMAN:

And so, there were — talk about the different Rides that went down and what happened to each.

STANLEY NELSON:

Well, the first twelve people were beaten so badly in Anniston and Birmingham that they had to stop, they had to quit.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to a clip of Freedom Riders.

JANIE FORSYTHE McKINNEY: The door burst open, and people just spilled out into the yard. They were practically tripping over each other because they were so sick and they needed to get some air.

MAE FRANCES MOULTRIE: I can’t tell you if I walked off the bus or if I crawled off or if someone pulled me off.

HANK THOMAS: When I got off the bus, a man came up to me, and I’m coughing and strangling. He said, “Boy, you all right?” And I nodded my head. And the next thing I knew, I was on the ground. He had hit me with part of a baseball bat.

MOSES NEWSOM: People were gagging, and they were crawling around on the ground. They were trying to get the smoke out of their chests. It was just an awful, awful, awful, awful scene.

JANIE FORSYTHE McKINNEY: It was horrible. It was like a scene from hell. It was the worst suffering I had ever heard.

STANLEY NELSON:

But then another wave of Riders came down from Nashville who were mostly students in Nashville. And they came down, and they were — they finally, after another ride in Montgomery, got to Jackson, Mississippi, where they were put in prison. They were put in the worst prison in the South, Parchman Penitentiary, which is the prison that we know with the black and white stripes and the chains and the chain gang. And they were put into Parchman.

And the governor, Ross Barnett, of Mississippi thought that that would break the back of the Freedom Rides. But then there was a call for more Freedom Riders, and it ended up over 400 Freedom Riders came from all over the country, and they kind of filled up the jails in Mississippi. And finally, the signs in the bus stations and the train stations that said “white only” and “colored only” were taken down as a result of the Freedom Rides.

AMY GOODMAN:

The role of President Kennedy, of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, his brother?

STANLEY NELSON:

Oh, one of the things that’s so interesting about the story is that the Kennedys are not the Kennedys that we know later on. You know, they really did not — they wanted to ignore the civil rights movement. They were so focused on foreign policy, and they were really beholden to the segregated South.

RAY ARSENAULT: It became clear that the civil rights leaders had to do something desperate, something dramatic, to get the Kennedys’ attention. So that was the idea behind the Freedom Rides, to dare the — essentially dare the federal government to do what it was supposed to do and see if their constitutional rights will be protected by the Kennedy administration.

STANLEY NELSON:

And the South voted solidly Democratic, so they were trying as best they could to stay out of the Freedom Rides, you know, and they just kept getting backed up and backed up and backed up, to where finally there was this dramatic siege in a church in Montgomery, where the Freedom Riders and the local, mostly black, community had come for a rally. There were 1,500 people trapped in the church by a mob of over 3,000 people, who were setting fires, turning over cars. And finally — they were trapped there until about 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning, and finally the federal troops were called out, and that was the only way they were saved from the church.

AMY GOODMAN:

And the relationship between the Kennedys and the governor?

STANLEY NELSON:

John Patterson, who is in the film, who’s still alive and in the film, was the first governor in the South to support John Kennedy when he was running for president, so, you know, they did not want to antagonize him. And he was an out-and-out racist. I mean, he ran on a segregated ticket. You know, he was very clear about it. And so, they did not want to confront him; they did not want to send troops into the South. So it was only after three riots and the church siege that they acted.

AMY GOODMAN:

And what about his avoiding them, not wanting to talk to him, allowing the violence to go on?

STANLEY NELSON:

Yeah, that’s one of the great moments in the film. It’s really a great story, where finally Robert Kennedy convinces his brother, JFK, to call John Patterson directly and say, “Look, you have to act.” And so, he calls him, and Patterson won’t take the call. And John Kennedy, the President of the United States, is pressing, is saying, you know, “Where is he? Where is he?” And John Patterson, in the film, was telling this story, and he tells his secretary to say he’s in the gulf fishing. And then he actually says in the film, you know, “I lied. I just lied about where I was.”

AMY GOODMAN:

So, talk about whether and when he transformed.

STANLEY NELSON:

I think he’s a different man today, and I think, you know, in some ways, he wasn’t the man that he appeared to be back then. I think that he felt that to be reelected — and, you know, he was elected on a segregation ticket — that this is what he had to do.

But I think that, you know, that the elected officials in the South were really, in some ways, responsible, you know, if any one person was responsible, for not stopping the violence, for inflaming the violence, for going — you know, he would go with the side of the mob, not against the mob. So when there were riots, he would say, “Well, it was the Freedom Riders’ fault for coming down here,” which is, you know, a completely irresponsible thing to do as a governor of a state.

AMY GOODMAN:

And the role of Dr. Martin Luther King?

STANLEY NELSON:

The role of King is really strange in the Freedom Rides, because he meets with the Freedom Riders in Atlanta, when they first get to Atlanta, and they ask him to go on the Ride, and he refuses. And he says, you know, “If I were you, I wouldn’t go on the Rides either, because I have reports that bad things are going to happen in Alabama.” So that’s the first — he refuses to go.

And then, after the second wave of Freedom Riders come and there’s a church siege, which Martin Luther King is part of the church siege — he’s in the church, because he comes down to support the Riders — they ask him again, “OK, we need you to go on the Ride. We need the high visibility that Martin Luther King will bring to this.” He still refuses to go. He says, you know, “I want to choose the moment of my own death.”

And he really ticks off a lot of the Freedom Riders, because they felt that having Martin Luther King would give them more publicity, but also the publicity makes it safer for you. So it’s really a start of what becomes, later on, a split in the civil rights movement, between some of the younger people and Martin Luther King.

AMY GOODMAN:

You’re steeped in civil rights history. What did you learn doing this film? What surprised you most, Stanley Nelson?

STANLEY NELSON:

Well, you know, I think it’s a film about what a few people can do if they just step forward. I mean, that’s what’s so amazing about the first twelve people who start the Freedom Rides. They have no backing. I mean, you know, everybody’s saying, “Don’t do this. You know, the South is —- you know, you’ll get killed!” But they do it. They do it, and they end up changing America forever. You know, the signs that say “white only,” “colored only,” which had been up for, you know, generations and generations, come down, because twelve people say, “You know, we’re just going to go out there and do it.” And I think that’s what’s important about the Freedom Rides.

AMY GOODMAN: —- premiered at Sundance last week. After break, we go to my interview with two Freedom Riders themselves. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As we begin Black History Month, we continue with the Freedom Riders. I spoke to two prominent civil rights activists who joined the Freedom Rides. This was in 1961. We sat down at the Sundance Film Festival and talked about this brave moment in history.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Well, I became a Freedom Rider because I was involved in the Nashville movement back in 1960. And I was one of the founders of SNCC, and we wanted to continue the work that we were doing, because we’d been so successful in desegregating the lunch counters. We said, “Wow, we have something now that’s going to work, that’s going to make a difference.” And this whole nonviolence training was the thing that really made the difference.

I was going to go on the original Freedom Ride in 1961 — in fact, John Lewis and I were going to go — but I needed parental permission, because I wasn’t going to be twenty-one until the summer, and they wouldn’t let me go. And I tried to get my parents, you know, to sign, and they say, “Well, you think we didn’t read this thing? We’re not going to sign your death warrant. You stay in school.” So, well, OK, I couldn’t go.

But once the bus got burned and the Freedom Ride stopped, I didn’t have to turn in any papers or get permission. In fact, because that happened, it gave me the freedom to be involved, because of what had happened to those other people.

AMY GOODMAN:

Explain what you mean.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Well, CORE was a sponsor of the Freedom Rides, and they’re the ones that required parental permission for anyone under twenty-one. But once CORE stopped the Freedom Rides and had the cooling-off period, that’s when the students from Nashville took over. So we didn’t need parental permission, because we — Diane Nash and John Lewis and those of us who were involved in Nashville — we weren’t obligated to any other organization.

AMY GOODMAN:

What about your parents?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Well, I felt that it was very important for me to do this. Some people were involved in the movement because they wanted to make things better for their grandchildren and, you know, those who would follow them. No, not me. I wanted to make things better so my grandparents would be able to enjoy this thing. So I had an urgency, and I had a passion, that I wanted to see it happen so in their lifetime, because of all they had experienced in the past, that they would be able to enjoy some of this in their lifetime.

AMY GOODMAN:

Jim Zwerg, talk about how you got involved with the Freedom Rides.

JIM ZWERG:

Well, I was also in Nashville. I was an exchange student from Beloit College attending Fisk. And one of the first people I met was John Lewis. I attended some workshops and got to meet people like Bernard and the others.

It was a very simple thing that started it. I asked some of my classmates if they wanted to go to a movie with me and was informed that we could not go to a movie together, because the movie theaters weren’t integrated.

AMY GOODMAN:

Were not integrated.

JIM ZWERG:

They were not integrated. So, ultimately, after a lot of soul searching and prayer, I got involved in Nashville in the stand-ins, and we had, the month before the Freedom Rides started, persevered, and the theaters had opened up, without any problems. And I had been selected at that time to be a part of the central committee, which was a group of about twenty-four students or so, representing the various colleges.

And when we learned that the CORE group left, our immediate response was, it’s got to go on. I was, at that time, the only male — white male involved in Nashville, and I felt very strongly that the group that went had to be integrated. And so I volunteered, and I was one of those selected to be among the first ten.

JIM ZWERG:

Students from the movement in Nashville had been through violence. We had been arrested. We had all had our lives threatened. We were ones that had not broken, and we were the logical ones to continue the Ride.

Tuesday, May 16, 1961. “We held two meetings today. The first was at 6 this morning, the second from 7 to 1 tonight. After much discussion, we decided to continue the Freedom Ride. Of the 18 who volunteered, 10 were chosen: three females and seven males. We will leave on the Greyhound bus tomorrow morning at either 5:15 or 6:45. We were all again made aware of what we can expect to face: jail, extreme violence or death.”

AMY GOODMAN:

So, where did you get on the bus?

JIM ZWERG:

We got on the bus in Nashville.

AMY GOODMAN:

What date?

JIM ZWERG:

The 17th — 16th — 17th — I’m getting old again. And as we were getting on the bus, the original plan was, we weren’t going to rock the boat at all. We wanted to get to Birmingham. We had talked to Reverend Shuttlesworth, and we had attempted to have him have people available to pick us up when we got to the bus station, rather than go in directly and demonstrate. We were going to go out into the community, hope that feelings would calm down a little bit, and then the next morning, prior to getting on the bus to go on to Montgomery, we would go back, and I would use the “colored” facilities, and they would use the “white” facilities.

Well, as we were getting on the bus, Paul Brooks was right ahead of me, and he looked to the back of the bus, and the back was fairly well full already. And he turned to me and said, “Jim, I don’t want to sit back there. Will you sit up front with me?” And I said yes. And so, from Nashville on, Paul and I were breaking the law. We sat two seats behind the bus driver.

AMY GOODMAN:

Black and white together.

JIM ZWERG:

Correct.

AMY GOODMAN:

Bernard Lafayette, describe this ride. When did your heart start to pump?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Well, when the first group, that Jim Zwerg was involved in, they got arrested in Birmingham. Well, we did have twenty-some students who were ready to drop out of school in the middle of their exams to go, and I was one of them. But we decided that what we should do is split the group in half, because if all of us go, then we all get arrested or we get killed or something, there wouldn’t be a cadre to follow up. So we decided what we’d do is let the first ten go, and I would be part of the second group. In fact I was spokesman for the second group. So when they got arrested in Birmingham, we said, “OK, now it’s time for us to go.”

We said, “Well, wait a minute. Suppose all ten of us get arrested?” So what we did was to divide it up. Five went by car, and the others went by train. And we wanted to rendezvous in Birmingham. But we didn’t know, in the meantime, while we were on our way down to Birmingham, Bull Connor has taken them out of jail and was bringing them back to the state line of Tennessee. So, during the night, we passed each other.

AMY GOODMAN:

Jim Zwerg, going to the state line, how scary was that?

JIM ZWERG:

Unfortunately, I didn’t get to go to the state line, because when we got to the Birmingham city limits, the bus was stopped, and Bull Connor arrested Paul Brooks and myself for disobeying an officer when we refused to give up our seats. I was put in the drunk tank with about forty various-stages-of-inebriated white Southerners. And so, when the others were taken out to the state line, Paul and I remained in jail, until the 19th, when we went to court. We were found guilty. And when they heard that the buses were going to take us on to Montgomery, we were released.

AMY GOODMAN:

Bernard Lafayette, talk about when Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King got involved with this.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Well, Dr. King came down when we had this mass meeting in Montgomery, when we continued the Freedom Rides from Birmingham.

Martin Luther King got involved when we had the violence at the bus station in Montgomery, and we had the mass meeting at the church. And he wanted to, you know, be there to show his support and that kind of thing. That’s when Martin Luther King was involved.

AMY GOODMAN:

Now, you all had asked him to join you on the Freedom Rides, but he refused. Were you in that meeting?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes. I was chairing the meeting, yes. And some of the students, particularly students who were from other states, who had been involved in SNCC, and also who were part of CORE or some other groups, because they felt that Martin Luther King would give the kind of visibility. And visibility sometimes meant some kind of security and protection, because the media played a very important role. Had it not been for the media, we don’t know whether we would have survived physically. And that’s one of the reasons why they attacked the media in Montgomery first. I was standing there. They went past us.

AMY GOODMAN:

And “they” are?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

These are the members of the Ku Klux Klan and other kind of people who were part of some hate groups and that kind of thing.

AMY GOODMAN:

The police?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

No, these were actually citizens.

AMY GOODMAN:

Right, but also, the police’s role?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes, well, policemen sat back and did nothing and allowed them to have about — well, they agreed on fifteen minutes, to rough us up, you know, and they agreed that they couldn’t kill us, but they could beat us up.

AMY GOODMAN:

They went after the journalists first?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

They went after journalists, smashed cameras, and that sort of thing.

AMY GOODMAN:

Who were you standing next to?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes, I saw a LIFE photographer. There were two of them. One was very tall and young, and the other was kind of short and a little chubby. And they started running. And they were trying to get the camera from the short guy. And I understand this LIFE reporter, who was a football player — and he was able to grab the camera and take off. They never — they couldn’t catch him at all. But this was at the bus station in Montgomery, Alabama, where Jim Zwerg, you know, was brutally beaten. But I was right there and saw the whole thing.

But now, on the issue of Martin Luther King, there was a debate. There was not consensus. What should be said is this: Martin Luther King went to jail many times, so going to jail was not an issue for him. His house had been bombed, with his wife and his baby there, OK? He had been a victim of many death threats and that kind of thing. So he was totally committed. So it was not out of a fear, for Martin Luther King. He was on probation in Georgia, because, remember, when Kennedy was running for president, he made — Kennedy made the phone call that helped to get Martin Luther King off the chain gang, because he had not changed his license when he moved from Alabama to Georgia. So that charge had nothing to do with the movement, per se. It was extreme, in giving someone six months because they didn’t get their license changed, but that was the maximum. But had Martin Luther King got arrested on the Freedom Rides, he would have been off serving a sentence in Georgia. So you have to look at the practicality of it. Yes, but he helped — he was there at the mass meeting. He was the spokesman for the group. And so, I was one of those who persuaded him not to come on the Freedom Rides, because we didn’t need him in jail. We needed him, you know, on the outside helping to raise money to get us out.

AMY GOODMAN:

Did it cause a rift with some of the other Freedom Riders, that he wouldn’t go, since they saw him as serious protection, that would —

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes.

AMY GOODMAN:

— a rift that would last for a while?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes, it did. And when you’re in a situation like we were in, you need all the help you could get. But I agree that people must play different roles at different times. So I was very much coming, you know, from the point of view of, we didn’t need Martin Luther King in jail this time.

AMY GOODMAN:

Jim Zwerg, what happened to you?

JIM ZWERG:

Well, I realized from my experience in Nashville that I was going to be a focus for violence, if there was going to be violence, in that the segregationists, if they hated anybody, they hated a white being with the blacks. I mean, I was called all the names, and I was a disgrace to the white race. And when I saw the mob coming, I realized that probably I was going to have some violence.

AMY GOODMAN:

And explain exactly where you were?

JIM ZWERG:

We were standing on the bus platform. We had gotten off the bus. When we first arrived, there was — it was very quiet.

AMY GOODMAN:

This was in Montgomery.

JIM ZWERG:

Yes. There were some of the media around. And John was our spokesman.

AMY GOODMAN:

John Lewis, the now congressman.

JIM ZWERG:

John Lewis. And we had gotten off the bus, and he was just stepping forward to respond to some questions.

JIM ZWERG:

And just as he is about to do this, this fella went at one of the fellas that was holding one of the parabolic mikes, and he grabbed it out of his hands, and he threw it to the ground, stomped on it, and turned and approached one of the photographers and grabbed his camera and yanked on it, and as doing so, the cameraman fell to the ground. He started kicking and beating him. And that seemed to be the cue.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

The mob came out and went straight to the reporters and started beating them and kicking them and throwing their cameras down, smashing them on the ground.

HERB KAPLOW: After we were forced away, that’s when the attack on the Riders themselves started.

FREDERICK LEONARD: It just seemed like, just suddenly, they were — we were like — the bus was like surrounded.

JIM ZWERG:

Just from around the bus bays and up the driveways and around the bus terminal, here came this mass of humanity screaming, you know, “Kill ’em! Get the [expletive]! Kill the [expletive]! Kill ’em! Kill ’em! Get ’em! Get ’em!” And you could see the weapons they were carrying, you know, hammers, bricks, chains, whatever. And you knew that there was going to be violence. And I bowed my head, and I asked God to be with me, to give me the strength to remain nonviolent and to forgive them. And basically, at that moment, I got grabbed and pulled into the mob.

AMY GOODMAN:

And what happened?

JIM ZWERG:

I got a thumpin’, a pretty severe thumpin’.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

He might not remember, but I was there, and I saw him, and what they did was knocked him over the rail. And then they picked him up and stood him in front of the rail again and knocked him over, knocked his teeth out. And they kept clobbering him and kicking him on the ground. And they took a crate, a cola crate, and hit John Lewis on the head, gashed him on the head. But I was there, and I saw what they were doing to him.

AMY GOODMAN:

And what did you then do? Jim Zwerg, you went off to the hospital. You were taken off. You were unconscious.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes.

AMY GOODMAN:

John Lewis?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

John Lewis was —

JIM ZWERG:

John was taken to the hospital. They were able to find some black ambulances, also segregated, that took both William Barbee and John. But nobody would take me. The white ambulances refused to take me. And so, I kind of laid on the tarmac for a while, and finally it was Floyd Mann who asked one of his associates if he — where his car was parked. And they were the ones that took me to the hospital.

AMY GOODMAN: Freedom Rider Jim Zwerg, recounting his experience of being attacked by a mob at the Montgomery bus station in May 1961. Zwerg was a student from Wisconsin. Bernard Lafayette was on the first Nashville-to-Montgomery Freedom Ride and is currently a professor at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology.

This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back with them in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As we continue with the Freedom Riders, the Reverend Bernard Lafayette and Jim Zwerg, I want to play a powerful clip from Stanley Nelson’s documentary Freedom Riders. This is about civil rights activist Diane Nash from Nashville, Tennessee. It begins with John Siegenthaler, who was the assistant to then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy. During the Freedom Rides, he had been sent to the South as the Kennedy administration’s chief negotiator with Alabama Governor John Patterson.

JOHN SIEGENTHALER: My phone in the hotel room rings, and it’s the Attorney General. And he opened the conversation: “Who the hell is Diane Nash? Call her and let her know what is waiting for the Freedom Riders.” So I called her. I said, “I understand that there are more Freedom Riders coming down from Nashville. You must stop them if you can.” Her response was, “They’re not going to turn back. They’re on their way to Birmingham, and they’ll be there shortly.”

You know that spiritual, “Like a tree standing by the water, I will not be moved”? She would not be moved. And I felt my voice go up another decibel and another, and soon I was shouting, “Young woman, do you understand what you’re doing? You’re going to get somebody — do you understand you’re going to get somebody killed?” And there’s a pause, and she said, “Sir, you should know, we all signed our last wills and testaments last night, before they left. We know someone will be killed.”

AMY GOODMAN: That was John Siegenthaler, talking about Freedom Rider Diane Nash in that excerpt from Freedom Riders.

We go back now to my conversation with the Freedom Riders Jim Zwerg and now the Doctor Reverend Bernard Lafayette, who were also, like Diane Nash, student activists in Nashville, Tennessee in 1961.

AMY GOODMAN: In the film Freedom Riders, it points out that Jimmy Hoffa, the union chief, said no bus drivers, Greyhound or Trailways — was it? — are going to ride these buses — they’re not going to drive them.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

I guess it was a union issue, but they knew it was very dangerous. When someone would burn the bus, like they did in Anniston, Alabama, it was not safe for whites or blacks. Even whites who were not involved in the Freedom Rides were just passengers. This mob that had no regard for anyone, and they just followed these buses, and they attacked them. They were very, you know, indiscriminate.

AMY GOODMAN:

But a driver did step forward to drive you.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes, on the condition that his supervisor would ride with him.

AMY GOODMAN:

Jim Zwerg, did you think President Kennedy, Attorney General Bobby Kennedy were on your side?

JIM ZWERG:

At the time, I’ve got to say I don’t think it was really a major issue that we were contemplating. We were so concerned that we felt the Ride continue, that nonviolence had to show that it could overcome whatever violence you threw at it, that we would ultimately prevail, that it wasn’t — for me, anyway —- a politically motivated thing one way or the other. It was -—

AMY GOODMAN:

The marshals were eventually brought in.

JIM ZWERG:

Yes.

AMY GOODMAN:

And where were they in this journey, Bernard Lafayette?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Well, they came when the mob surrounded us at the church. The federal marshals came in.

AMY GOODMAN:

When Dr. King was inside.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes.

AMY GOODMAN:

And the other leaders.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Exactly. This mob would not go away. They threw bricks and broke stained-glass windows in the church.

AMY GOODMAN:

How many outside?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

About 3,000, estimated.

AMY GOODMAN:

How many of the people were inside, the civil rights activists?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Probably about 1,500.

AMY GOODMAN:

Dr. King was on the phone with Attorney General Bobby Kennedy?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes, he was, and Diane Nash, as well.

AMY GOODMAN:

Diane Nash, the civil rights leader, as well.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Right. She was our youth leader for our students and that kind of thing. And Martin Luther King represented the adult organizations, as well. And James Farmer, who was there, from CORE, he had returned; his father had been funeralized, and he had returned to the Freedom Riders by then.

And so far as the Kennedys were concerned, they wanted to get this thing over with. In fact, they wanted to stop it, because they didn’t want people to get killed. So they asked for a cooling-off period, because they couldn’t get any support or protection from the governor of Alabama. And in terms of our nonviolent movement, we wanted to continue to move forward. And we were trained in nonviolence.

But there’s one thing that’s not well known that’s very important, and there was some taxi drivers there in Montgomery, black cab taxi drivers. And we had received word that they were mobilizing and arming themselves to come and rescue us. And there were a large number of cab drivers and taxi companies in Montgomery, because during the boycott a lot of people started driving their cars. They had twenty-seven black cab companies in Montgomery, and some of them only had two cabs.

But the thing that really struck me, and I’ll never forget, is that Martin Luther King stood in the pulpit of the church, the First Baptist Church, when a mob was surrounding the church, and he said, “I want some — I want a few people who really are sure about their nonviolence, because we’ve got a special mission.” And everybody did not volunteer, including a lot of the ministers, but he got a little group together, maybe about eight or ten maybe. He walked out of that church, through the mob, to dissuade those cab drivers from coming with arms to rescue us. This was before the marshals show up. And then he walked back through the mob. Now that is one mystery in the whole thing that I have never been able to fathom.

JIM ZWERG:

Daniel and the lion’s den.

AMY GOODMAN:

John Siegenthaler, the President — the Attorney General’s envoy to you, what happened to him?

JIM ZWERG:

Well, I was out, but —

AMY GOODMAN:

You were unconscious, you mean, Jim?

JIM ZWERG:

I was unconscious. The story is that he heard and became aware of what was going on, and as he was driving towards the bus terminal, he saw Susan Wilbur and Susan Hermann.

AMY GOODMAN:

They are?

JIM ZWERG:

Those were two of the white students who were also exchange — well, one was an exchange student, Susan Hermann, at Fisk. Susan Wilbur came and was from Peabody and was from Nashville, wasn’t she?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes.

JIM ZWERG:

As I recall. And as he drove up, there was a young teenager just poppin’ these gals. And he went in and grabbed Susan Wilbur and kind of tried to get her in the car, said, “Get in the car.” And she grabbed the side, and she said, you know, “This is not your fight. Don’t get involved with this. I’m trained in nonviolence.” And about that moment, somebody got to Siegenthaler and said, “Who are you?” And he said, “I’m a representative of the United States government.” And somebody hit him with a pipe, and he was out.

AMY GOODMAN:

Let’s go to a clip of Freedom Riders.

REV. JAMES LAWSON: We did not ask for all of the state police and the helicopters overhead. It was shameful that we could not travel peacefully without that apparatus of protection.

REPORTER: At 11:50 a.m. Central Standard Time, the bus hit the Mississippi line, and the Alabama authority is pulling back.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

We felt a very strange feeling when the changing of the guard at the Alabama-Mississippi state line. It was very eerie. In spite of all that Alabama had done, the fear of Mississippi in the minds of many people was far greater. There was a huge billboard, and that billboard said, “Welcome to Mississippi, the Magnolia State.” And when we continued to ride on, the next large sign we saw said, “Prepare to meet thy God.”

AMY GOODMAN:

As we wrap up, how this all ended, and what it meant to each of you? Dr. Bernard Lafayette?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

What happened is from two different points of view. One had to do with how do we go about trying to end discrimination and segregation in public transportation, because this was an area of segregation that affected a large number of people all over. And it shows a drastic contrast between the North and the South, because we didn’t have the segregation in the public transportation in the North. In fact you had to change buses and change train cars when you went North, and that was very dramatic when we made travel like that. So, on that particular issue, it was important.

The other thing that was important was the fact that it was a new way of organizing social movements and social change struggle. In the past, we had the legal struggle, where you go to the courts and you get some kind of court ruling, and you appeal all the way to the Supreme Court. The lawyers were trained, Thurgood Marshall and all those, that whenever you take a simple case like someone getting arrested for a sit-in in the wrong place or whatever, you build a case as if you’re going to the Supreme Court. You’re trained to do it. And that was a battle, that was a fight, the lawyers.

Martin Luther King introduced another whole approach. In addition to the legal struggle, we had to work not only on legislative things, and that was another way of struggling, trying to get the law changed through Congress, but we got the masses of people involved. And that’s when the Freedom Rides changed. You didn’t have a select group of people who could be, you know, disciplined, and certain people that you were aware of. But when the masses of people got involved, and you had over 400 people get involved in the Freedom Rides — so we had to then change our strategy, not go to New Orleans. But when they started arresting us in Jackson, Mississippi, we made that our battleground, to fill the jails. And the purpose of filling the jail was to get more people, individuals, actively involved and participating in the movement, because Martin Luther King believed that a change would come when people themselves had a chance to change and had a chance to be involved.

AMY GOODMAN:

And being imprisoned at Parchman Prison, one of the most notorious prisons?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE: Yes, that meant serious commitment. And by the way, the largest single group, when the demographic study was done, the single group that was there on the Freedom Rides arrested in Parchman was young Jewish women from Chicago. And that was because a professor at the University of Chicago said that he was going on a Freedom Ride, and his class said, “Can we go?”

AMY GOODMAN:

Let’s go back to a clip of Freedom Riders.

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

We made up a song saying that buses are a-coming. And we sang it to the jailers to tell them, and warn them, to get ready, to be prepared, that we were not the only ones coming. So we started singing, [singing] “Buses are a-comin’, oh, yes, buses are a–comin’, oh, yes, buses are a-comin’, buses are a-comin’, buses are a-comin’, oh, yes.”

And we say to the jailers, [singing] “Better get you ready, oh, yes.” The jailers say, “Alright, shut up on the singing and hollering in here! This is not no playhouse. This is a jailhouse.” So we said to ourselves, “What are you going to do? Put us in jail?”

AMY GOODMAN:

Jim Zwerg, how did this affect your life?

JIM ZWERG:

My involvement totally changed my life when I embraced nonviolence. The first person that changes is you, the individual who embraces it. Then it changes the way you look at others, as well. My life has been dedicated to sharing that message through the ministry and through just life in general. To this day, I go and speak with children, and adults of all ages, talking about nonviolence and the steps to bring about social change, principles of nonviolence.

Knowing people like this guy, my brother, and when we get together — here we are seventy years old — well, he’s a young sprite; I’m seventy — but all those memories come flooding back, the love, the fellowship, the relationships we had, the joys we shared, the triumphs. It was the most incredible period in my life, and I will cherish it, and I have been deeply, deeply blessed to call people like Bernard my dear friends.

AMY GOODMAN:

Do you see the same passion for social change today as you did then? Do you think it needs to happen?

BERNARD LAFAYETTE:

Yes, we have to teach our young people, and because what surprises me is, then, lately, that these young people don’t know anything about the struggle. They don’t know anything. There’s a terrible gap, serious, not just generation gap, information gap. And that’s why I’m really so excited about this production and this film presentation, because it’s going to educate a lot of our young people, and we’re going to close the gap.

JIM ZWERG:

It’s very powerful.

AMY GOODMAN:

I want to thank you both for being with us and for your bravery.

AMY GOODMAN:

Jim Zwerg and the Reverend Doctor Bernard Lafayette.

Media Options