Guests

- Gabor MatéVancouver, Canada-based physician and author. He is staff physician at the Portland Hotel Society, which runs a residence and harm reduction facility as well as Insite, North America’s only supervised safe-injection site. His four books, all bestsellers in Canada, include Scattered: How Attention Deficit Disorder Originates and What You Can Do About It, When the Body Says No, and his latest, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction.

Links

Dr. Gabor Maté is the staff physician at the Portland Hotel Society, which runs a residence/harm reduction facility and North America’s only supervised safe-injection site in Vancouver, Canada, home to one of the world’s densest areas of drug users. The bestselling author of four books, we speak to Dr. Maté about his latest, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, which proposes new approaches to treating addiction through an understanding of its biological and socio-economic roots. Maté also discusses his work on attention deficit disorder and the mind-body connection. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The Obama administration’s budget proposal for the Office of National Drug Control Policy sets aside nearly twice the amount of funding for law enforcement and criminalization than for treatment and prevention of drug addiction. Out of a total of $15.5 billion, some $10 billion are used for enforcement. National Drug Control Policy Gil Kerlikowske praised the numbers as reflecting a “balanced and comprehensive drug strategy.”

Well, just last year, the newly appointed drug czar and former Seattle police chief had called for an end to the so-called “war on drugs,” raising hopes among advocates of harm-reduction approaches to curbing drug use. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal last May, Kerlikowske said, “People see a war as a war on them. We’re not at war with people in this country.”

Well, I’m joined right now here in the Democracy Now! studio by a doctor who has spent the last twelve years working with one of the densest populations of drug addicts in the world. Dr. Gabor Maté is the staff physician at the Portland Hotel, a residence and harm reduction facility in Vancouver, Canada’s Downtown Eastside. Dr. Maté also treats addicts at the only safe-injection site in North America, a center that’s come under fire from Canada’s Conservative government led by Stephen Harper.

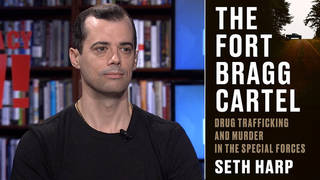

Dr. Gabor Maté is the bestselling author of four books. His latest, just out in the United States, is called In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Dr. Maté.

DR. GABOR MATÉ: Pleasure to be here.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, what do you mean, the only safe-injection site, the only legal injection site in North America? People inject heroin there?

DR. GABOR MATÉ: People are allowed to bring their drugs there. We don’t provide them with their drugs. I think we should, but we don’t. But they bring it in, and without fear of being arrested, they’re allowed to inject, under supervision. And the staff, without being fear arrested, are allowed to help them inject in a safe way, give them clean needles, sterile swabs, and resuscitate them if they overdose. So, everywhere else in Canada or in the States, of course, these activities would all be illegal.

AMY GOODMAN: Why are they allowed to do this?

DR. GABOR MATÉ: Well, it was conceived in a moment of political openness, because so many people pass on infections, like HIV and hepatitis C, to one another through injection use, sharing needles. They infect themselves with bacteria from their skin by using dirty water. So it’s a harm reduction measure that, in many studies, have been shown to reduce the burden of disease and also the economic costs attendant to addiction to society.

AMY GOODMAN: And do you find that addicts can actually heal themselves or perhaps be able to get off heroin more easily by injecting there?

DR. GABOR MATÉ: Well, the facility is not designed to treat addiction, per se; it’s designed to reduce the harm from it. It’s a harm reduction measure. What we do find, though, is that we have a detox facility on the second floor, which is where I’ve been working, and people come from the injection facility to detox, because they’ve been into —- brought into contact with compassionate caregivers perhaps for the first time in their lives. These people all had very tough lives. And so, for them to even contemplate receiving help takes a lot of trust.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the people you treat.

DR. GABOR MATÉ: Well, the hardcore drug addicts that I treat, but according to all studies in the States, as well, are, without exception, people who have had extraordinarily difficult lives. And the commonality is childhood abuse. In other words, these people all enter life under extremely adverse circumstances. Not only did they not get what they need for healthy development, they actually got negative circumstances of neglect. I don’t have a single female patient in the Downtown Eastside who wasn’t sexually abused, for example, as were many of the men, or abused, neglected and abandoned serially, over and over again.

And that’s what sets up the brain biology of addiction. In other words, the addiction is related both psychologically, in terms of emotional pain relief, and neurobiological development to early adversity.

AMY GOODMAN: What does the title of your book mean, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts?

DR. GABOR MATÉ: Well, it’s a Buddhist phrase. In the Buddhists’ psychology, there are a number of realms that human beings cycle through, all of us. One is the human realm, which is our ordinary selves. The hell realm is that of unbearable rage, fear, you know, these emotions that are difficult to handle. The animal realm is our instincts and our id and our passions.

Now, the hungry ghost realm, the creatures in it are depicted as people with large empty bellies, small mouths and scrawny thin necks. They can never get enough satisfaction. They can never fill their bellies. They’re always hungry, always empty, always seeking it from the outside. That speaks to a part of us that I have and everybody in our society has, where we want satisfaction from the outside, where we’re empty, where we want to be soothed by something in the short term, but we can never feel that or fulfill that insatiety from the outside. The addicts are in that realm all the time. Most of us are in that realm some of the time. And my point really is, is that there’s no clear distinction between the identified addict and the rest of us. There’s just a continuum in which we all may be found. They’re on it, because they’ve suffered a lot more than most of us.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the biology of addiction?

DR. GABOR MATÉ: For sure. You see, if you look at the brain circuits involved in addiction -— and that’s true whether it’s a shopping addiction like mine or an addiction to opiates like the heroin addict — we’re looking for endorphins in our brains. Endorphins are the brain’s feel good, reward, pleasure and pain relief chemicals. They also happen to be the love chemicals that connect us to the universe and to one another.

Now, that circuitry in addicts doesn’t function very well, as the circuitry of incentive and motivation, which involves the chemical dopamine, also doesn’t function very well. Stimulant drugs like cocaine and crystal meth, nicotine and caffeine, all elevate dopamine levels in the brain, as does sexual acting out, as does extreme sports, as does workaholism and so on.

Now, the issue is, why do these circuits not work so well in some people, because the drugs in themselves are not surprisingly addictive. And what I mean by that is, is that most people who try most drugs never become addicted to them. And so, there has to be susceptibility there. And the susceptible people are the ones with these impaired brain circuits, and the impairment is caused by early adversity, rather than by genetics.

AMY GOODMAN:

What do you mean, “early adversity”?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, the human brain, unlike any other mammal, for the most part develops under the influence of the environment. And that’s because, from the evolutionary point of view, we developed these large heads, large fore-brains, and to walk on two legs we have a narrow pelvis. That means — large head, narrow pelvis — we have to be born prematurely. Otherwise, we would never get born. The head already is the biggest part of the body. Now, the horse can run on the first day of life. Human beings aren’t that developed for two years. That means much of our brain development, that in other animals occurs safely in the uterus, for us has to occur out there in the environment. And which circuits develop and which don’t depend very much on environmental input. When people are mistreated, stressed or abused, their brains don’t develop the way they ought to. It’s that simple. And unfortunately, my profession, the medical profession, puts all the emphasis on genetics rather than on the environment, which, of course, is a simple explanation. It also takes everybody off the hook.

AMY GOODMAN:

What do you mean, it takes people off the hook?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, if people’s behaviors and dysfunctions are regulated, controlled and determined by genes, we don’t have to look at child welfare policies, we don’t have to look at the kind of support that we give to pregnant women, we don’t have to look at the kind of non-support that we give to families, so that, you know, most children in North America now have to be away from their parents from an early age on because of economic considerations. And especially in the States, because of the welfare laws, women are forced to go find low-paying jobs far away from home, often single women, and not see their kids for most of the day. Under those conditions, kids’ brains don’t develop the way they need to.

And so, if it’s all caused by genetics, we don’t have to look at those social policies; we don’t have to look at our politics that disadvantage certain minority groups, so cause them more stress, cause them more pain, in other words, more predisposition for addictions; we don’t have to look at economic inequalities. If it’s all genes, it’s all — we’re all innocent, and society doesn’t have to take a hard look at its own attitudes and policies.

AMY GOODMAN:

Can you talk about this whole approach of criminalization versus harm reduction, how you think addicts should be treated, and how they are, in the United States and Canada?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, the first point to get there is that if people who become severe addicts, as shown by all the studies, were for the most part abused children, then we realize that the war on drugs is actually waged against people that were abused from the moment they were born, or from an early age on. In other words, we’re punishing people for having been abused. That’s the first point.

The second point is, is that the research clearly shows that the biggest driver of addictive relapse and addictive behavior is actually stress. In North America right now, because of the economic crisis, a lot of people are eating junk food, because junk foods release endorphins and dopamine in the brain. So that stress drives addiction.

Now imagine a situation where we’re trying to figure out how to help addicts. Would we come up with a system that stresses them to the max? Who would design a system that ostracizes, marginalizes, impoverishes and ensures the disease of the addict, and hope, through that system, to rehabilitate large numbers? It can’t be done. In other words, the so-called “war on drugs,” which, as the new drug czar points out, is a war on people, actually entrenches addiction deeply. Furthermore, it institutionalizes people in facilities where the care is very — there’s no care. We call it a “correctional” system, but it doesn’t correct anything. It’s a punitive system. So people suffer more, and then they come out, and of course they’re more entrenched in their addiction than they were when they went in.

And by the way, according to many studies, the easiest place to get drugs is in prisons — and in schools, by the way. These are the two areas where you can get drugs in North America: the schools and the prisons. So that it makes no sense from any point of view. It serves some people, perhaps, with entrenched interests, but it does not serve the addict, nor does it serve society.

And I could tell you something else about that. A patient of mine with a $50 cocaine habit a day, which is not excessive, how does he raise money to be able to afford those drugs? By shoplifting. To reach $50 a day, he has to shoplift $500 worth of goods. Who pays for that? The social cost is way beyond the cost of law enforcement.

AMY GOODMAN:

Wasn’t there an attempt to shut down the clinic that you have in Vancouver by the federal government in Canada?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, the federal government we have in Canada right now, the Harper government, is — got its stuck head very much in the sands of Bush-era attitudes. And they never liked the idea of a supervised injection site, and they’ve tried to shut it down, and twice now, in the Supreme Court of British Columbia and in appeal court. Their attempt has been defeated, because the courts have ruled that this is a necessary medical service which the government does not have the right to withdraw. And, of course, twenty-four international studies have attested to that, but the government ignores the medical information.

AMY GOODMAN:

You’re headed back to Vancouver, where the Olympics are beginning next week.

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Yes.

AMY GOODMAN:

What is the effect of the Olympics on the community, especially when it comes to social services?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, in the Downtown Eastside, there’s a real fear, because the last time there was a big international event in Vancouver, which was Expo, the police simply took street people off the streets and shipped them out of Vancouver. They put them on buses. Now, nobody’s clear that that’s going to happen this time, and probably not, because the political organization amongst people in the Downtown Eastside is much stronger now.

But certainly, I live in an area of the world where we’re building highways now so that rich people can see skiing events, whereas social services are being cut. There’s a danger of teachers being let go because of the typical North America-wide economic squeeze. And drug programs in northern British Columbia that serve aboriginal youth have been cut now because of budgetary constraints. At the same time, we’re building skating rinks. So it’s usually the people at the very bottom who pay the price for the people who are well-to-do to have a good time.

AMY GOODMAN:

I’m curious about your own history, Gabor Maté.

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN:

You’ve written a number of bestselling books. We won’t get to talk about them all. I’m very interested in your one on how attention deficit disorder originates and what you can do about it. But about your own history, you were born in Nazi-occupied Hungary?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, ADD has a lot to do with that. I have attention deficit disorder myself. And again, most people see it as a genetic problem. I don’t. It actually has to do with those factors of brain development, which in my case occurred as a Jewish infant under Nazi occupation in the ghetto of Budapest. And the day after the pediatrician — sorry, the day after the Nazis marched into Budapest in March of 1944, my mother called the pediatrician and says, “Would you please come and see my son, because he’s crying all the time?” And the pediatrician says, “Of course I’ll come. But I should tell you, all my Jewish babies are crying.” Now infants don’t know anything about Nazis and genocide or war or Hitler. They’re picking up on the stresses of their parents. And, of course, my mother was an intensely stressed person, her husband being away in forced labor, her parents shortly thereafter being departed and killed in Auschwitz. Under those conditions, I don’t have the kind of conditions that I need for the proper development of my brain circuits. And particularly, how does an infant deal with that much stress? By tuning it out. That’s the only way the brain can deal with it. And when you do that, that becomes programmed into the brain.

And so, if you look at the preponderance of ADD in North America now and the three millions of kids in the States that are on stimulant medication and the half-a-million who are on anti-psychotics, what they’re really exhibiting is the effects of extreme stress, increasing stress in our society, on the parenting environment. Not bad parenting. Extremely stressed parenting, because of social and economic conditions. And that’s why we’re seeing such a preponderance.

So, in my case, that also set up this sense of never being soothed, of never having enough, because I was a starving infant. And that means, all my life, I have this propensity to soothe myself. How do I do that? Well, one way is to work a lot and to gets lots of admiration and lots of respect and people wanting me. If you get the impression early in life that the world doesn’t want you, then you’re going to make yourself wanted and indispensable. And people do that through work. I did it through being a medical doctor. I also have this propensity to soothe myself through shopping, especially when I’m stressed, and I happen to shop for classical compact music. But it goes back to this insatiable need of the infant who is not soothed, and they have to develop, or their brain develop, these self-soothing strategies.

AMY GOODMAN:

How do you think kids with ADD, with attention deficit disorder, should be treated?

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Well, if we recognize that it’s not a disease and it’s not genetic, but it’s a problem of brain development, and knowing the good news, fortunately — and this is also true for addicts — that the brain, the human brain, can develop new circuits even later on in life — and that’s called neuroplasticity, the capacity of the brain to be molded by new experience later in life — then the question becomes not of how to regulate and control symptoms, but how do you promote development. And that has to do with providing kids with the kind of environment and nurturing that they need so that those circuits can develop later on.

That’s also, by the way, what the addict needs. So instead of a punitive approach, we need to have a much more compassionate, caring approach that would allow these people to develop, because the development is stuck at a very early age.

AMY GOODMAN:

You began your talk last night at Columbia, which I went to hear, at the law school, with a quote, and I’d like you to end our conversation with that quote.

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Would that be the quote that only in the presence of compassion will people allow themselves —

AMY GOODMAN:

Mahfouz.

DR. GABOR MATÉ:

Oh, oh, no, yeah, Naguib Mahfouz, the great Egyptian writer. He said that “Nothing records the effects of a sad life” so completely as the human body — “so graphically as the human body.” And you see that sad life in the faces and bodies of my patients.

AMY GOODMAN:

Well, Dr. Gabor Maté, I want to thank you very much for being with us. His latest book is called In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. Before that, Scattered: How Attention Deficit Disorder Originates and What You Can Do About It and When the Body Says No: Understanding the Stress-Disease Connection.

Media Options