Guests

- Dr. Theo Colbornzoologist and president of the the Endocrine Disruption Exchange

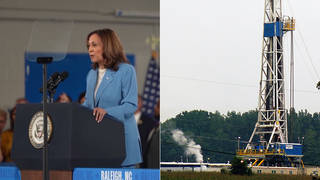

The Environmental Protection Agency has begun a review of how the drilling process known as hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” can affect drinking water quality. We speak to Dr. Theo Colborn, the president of the Endocrine Disruption Exchange and one of the foremost experts on the health and environmental effects of the toxic chemicals used in fracking. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN:

Right now, we’re turning to a health issue here in this country. Sharif?

SHARIF ABDEL KOUDDOUS:

That’s right. We’re going to look at the health impacts of natural gas drilling. As the Environmental Protection Agency begins its review of how the drilling process known as hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” can affect drinking water quality, the gas industry is raising new objections. The Independent Petroleum Association of America told the EPA its intended research, quote, “goes well beyond relationships between hydraulic fracturing and drinking water.” The findings could lead Congress to repeal an exemption that shields the fracturing process from federal regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

AMY GOODMAN:

Well, as the debate over shale gas drilling heats up, we’re joined here in New York by Dr. Theo Colborn, zoologist and president of the Endocrine Disruption Exchange. She’s one of the foremost experts on health and environmental effects of the toxic chemicals used in fracking fluid.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Dr. Colborn.

DR. THEO COLBORN:

Amy, it’s great to be here with you.

AMY GOODMAN:

Well, it’s great to have you in our studio. Start off by explaining what fracking is. What is hydraulic fracturing?

DR. THEO COLBORN:

Well, you know, you first have to drill a hole. And fracking goes one step beyond drilling the hole. In other words, the gas comes up out of the hole, but eventually you want to get more gas. And to facilitate that, there’s a now technology called fracking. Actually, industry calls it “stimulating.” And that’s to make it more, you know, citizen-, public-wise acceptable.

But basically, it causes many earthquakes underneath the ground. They put chemicals in large amounts of fluids. Basically, if you’re going to be drilling in the New York City watershed, say, you’re going to be using between three and eight million gallons of water, which may be carrying tons of toxic chemicals that eventually — no one really knows where they’re going to go.

Now, when they fracture, as they go down in the hole, the chemicals are added over a sequence of time, because they’re put in there for various purposes. But when the little mini-explosion takes place underground, that may extend as far as 2,000 feet out from the borehole. And consequently, that extends then this ability of this fracturing process to work. Now, that’s from a direct drilled pipe, and we’ve been using that process for years. More recently, they’ve gone into what they call horizontal fracturing, where as they drill the pipe down in, they bend the pipe, so that the pipe then goes off horizontally below the ground. And that can extend another 2,000 feet.

So the beauty of fracturing, of course, is that you don’t have to make as many perforations on the ground, above, where the people are living, but you also have this access to maybe a radius of a mile or more around where each borehole goes into the ground.

SHARIF ABDEL KOUDDOUS:

Well, let’s turn to a clip from this documentary Split Estate that investigates fracking. This clip features Weston Wilson, an environmental engineer in the EPA’s Denver office. In 2004, Wilson openly questioned an EPA study that declared fracking poses little or no threat to drinking water.

WESTON WILSON: The former chairman, CEO of Halliburton, Dick Cheney, within a few months of coming into office, and as vice president, he was pressuring the administrator of EPA, Christie Todd Whitman, to exempt hydraulic fracking from the Safe Drinking Water Act regulation.

From my own view as a technician, I just thought it very alarming that EPA technically had described how toxic these materials are — toxic at the point of injection — and still come out with a summary that says they don’t need to be reported or regulated. And that led me, in the fall of ’04, to object on technical grounds. Then the inspector general of EPA began an investigation of my complaints.

And several months into that, Congress took the report from EPA saying that fracking did not present a risk, along with other information, and exempted hydraulic fracking from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. That leaves you and I, as the American public, in this position: we cannot know what the industry injects in our land. It is exempt from being reported.

SHARIF ABDEL KOUDDOUS:

That was Weston Wilson, an environmental engineer in the EPA’s Denver office, speaking in 2004. Dr. Theo Colborn, your thoughts on what he was saying on this issue of disclosure?

DR. THEO COLBORN:

Well, exactly. It’s very interesting. We’ve been trying to get information on the chemicals that are used to fracture —- well, actually, drilling and fracturing. Drilling has its problems, as well. We must not overlook that. And over the years, with the help of government datas and then also information that we’ve basically collected because of accidents and spills, we’ve been able to put together a database in which we have 944 products listed now that are being used in the states where natural gas activity is taking place.

Now, out of those 944 chemicals, we know between 95 and 100 percent of about 14 percent of the chemicals that are being used. We know what they are in those products. But we also have 43 percent of the products that are being used, we know absolutely nothing. We have no idea what’s in those forty-two-gallon drums or the 350— or 360-gallon totes. So we’re dealing with —- the information that we’re working with is only based on a very small percentage of the products that are being used. And then -—

AMY GOODMAN:

So, let’s talk about the health — go ahead.

DR. THEO COLBORN:

But the problem here is, what Wes is talking about is, 70 percent — 30 to 70 percent of that water that’s injected underground can possibly come back up to the surface. No one knows exactly how much stays underground and how much is going to be coming back up to the surface. So you worry about the long-term effect of that material that’s staying underground, that could appear later coming up in rivers and streams, at people’s well sites, that sort of thing, because we don’t understand the geology underground. But then all that — the rest of that has to come back up. And what people don’t realize is that gas doesn’t come up out of the ground dry, either; it comes up wet. So we have the water we’re taking off of the gas that is not clean, and we have the water that’s coming back up from fracturing.

AMY GOODMAN:

We don’t have much time, but we want to talk about the health effects. You are the president of the Endocrine Disruption Exchange.

DR. THEO COLBORN:

That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN:

Explain what endocrine disruption is and how that relates to these chemicals that you are beginning to identify.

DR. THEO COLBORN:

Well, it’s amazing, Amy. We were really stunned when we began breaking out the chemicals by their major health effects, and we found that 43 percent of the chemicals in Colorado, in those that are used there, are endocrine disruptors. Now, and in our national survey, it’s 37 percent.

But what endocrine disruption does, basically, these are the chemicals that we now understand better — by the way, that are made from natural gas, believe it or not — the plastics that — and pesticides and other industrial chemicals. These are the chemicals that can get into the pregnant woman and enter the womb, while her baby is developing in her womb, and alter how those children are born. And this is our big concern today, because we’re facing major pandemics of endocrine-driven disorders — simple things like ADHD, autism, diabetes, obesity, early testicular cancer, endometriosis. These are all endocrine-driven disorders that we’re very concerned about.

And these products are being injected underground, for centuries, maybe, to stay before they surface, and also coming back up. So the big problem is — with natural gas, is dealing with the water when it comes back up.

SHARIF ABDEL KOUDDOUS:

And the EPA now is conducting a national study looking at natural gas drilling. What do you think is the significance of the study, and is it funded well enough?

DR. THEO COLBORN:

Well, I’m concerned about the funding, actually, and the time limit on it, too. It’s been given to the Office of Research and Development. Dr. Paul Anastas is now running that division of EPA, which was a great appointment by Obama recently, and I have a lot of faith in him. But there is — you know, it’s easy to go into a laboratory and set up some test tubes and run an experiment. But you’re working with undefined geology that shifts. Every single place you go, the geology is different, the hydrology is different. And for them to be able to get out there, and in two years, with only $2 million, try to resolve this problem, I don’t think they can do it.

And I did sit in on their day-and-a-half meeting that they had in Washington about the plans they’re thinking about and how they’re going to move forward to do this study. And I’m afraid they’re going to get into what is called the stakeholder process. They’re going to bring in people who know nothing about it, representing all the stakeholders, just like they did with the endocrine disruption panel that they put together in 1996.

AMY GOODMAN:

We have five seconds.

DR. THEO COLBORN:

Five seconds, OK.

But when you give it to the stakeholders, and you don’t give it to the scientists, you’re — we’ve got to separate the research that we’re doing behind all of this work that’s going on from those — the corporate-controlled decision makers.

AMY GOODMAN:

And, of course, we’re going to continue to follow this, because, well, under the guise of energy independence, this whole issue of natural gas drilling is really coming to the fore in this country. Dr. Theo Colborn, thank you so much for being with us.

Media Options