Related

Guests

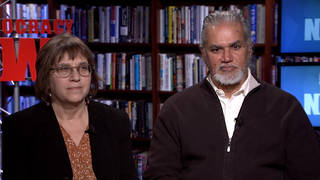

- Monique HardenNew Orleans attorney and co-director of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights.

- Amory Lovinsco-founder, chairman and chief scientist of Rocky Mountain Institute in Colorado.

- Michael Bruneexecutive director of The Sierra Club. His book is Coming Clean: Breaking America’s Addiction to Oil and Coal.

We host a discussion on how the Obama administration has handled this catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico and explore concrete ways that this country might finally move away from a fossil-fuel economy with three guests: New Orleans attorney Monique Harden of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights; Sierra Club executive director Michael Brune; and Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute in Colorado, widely recognized as one of the world’s most influential energy thinkers. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Well, today we host a roundtable discussion on how the Obama administration has handled this catastrophe in the Gulf of Mexico, what he called, quote, “an epidemic” and a “tragedy.” And we’ll talk about concrete ways that this country might finally move away from a fossil fuel economy.

We’re joined by three guests: from New Orleans, Louisiana, attorney Monique Harden, she co-directs Advocates for Environmental Human Rights; from Washington, DC, the executive director of the Sierra Club, Michael Brune, author of Coming Clean: Breaking America’s Addiction to Oil and Coal; and joining us via Democracy Now! video stream is Amory Lovins, co-founder, chair and chief scientist at the Rocky Mountain Institute in Colorado, widely recognized as one of the world’s most influential energy thinkers, author of a number of books, including Winning the Oil Endgame, Small Is Profitable, and Natural Capitalism.

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! But let’s go directly to New Orleans. Let’s go to, well, near ground zero, to Monique Harden. Can you respond to President Obama’s address and what is happening now not so far from where you are in the Gulf of Mexico?

MONIQUE HARDEN: Well, I thought the President’s Oval Office address last night, you know, laid out points that I think people in the region would be agreeable with: the fact that clearly since Hurricane Katrina we have suffered a failed recovery, that we do need to give up this dependence on the fossil fuel industries that have really damaged extensively communities throughout the Gulf region, whether it’s from offshore drilling and the spills that have occurred before the BP disaster, coastal erosion from the channelization of wetlands for an extensive network of oil and gas pipelines. And then, as you go further inland, some of the most toxic production facilities in America are outside the homes of many African American communities, especially in the state of Louisiana. So I think, in broad brush strokes, he laid out a vision for what the future could be, as well as dealing with the critical needs that we have right now of capping the oil and ensuring that people are able to fully recover through adequate and just compensation.

AMY GOODMAN: You have written a letter to Thad Allen, who is in charge of dealing with the whole oil spill from the government side. We’re going to go to a break, but when we come back, I want to find out what that’s about, and then we’ll also speak with Amory Lovins and Michael Brune.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report. Back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama has given his first Oval Office address, and it’s about the oil that is gushing out of the seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico. We are talking today about how the government and the corporation are dealing with this and where we go from here. Our guests, Monique Harden, attorney and co-director of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights; Amory Lovins, chief scientist at Rocky Mountain Institute; and Michael Brune, executive director of Sierra Club.

Monique, why did you write a letter to Thad Allen?

MONIQUE HARDEN: Well, we thought it was — at Advocates for Environmental Human Rights, we thought it was extremely important that Thad Allen, as the national incident commander, not just be concerned about the data regarding BP’s processing of claims by fishermen, oyster farmers and shrimpers and businesses and communities along the Gulf region impacted by the disaster of its oil spill that’s hemorrhaging from the Gulf, but that it was really important to understand the motivations that BP has with a contractual relationship, a company called ESIS, that made it very clear on their website that their focus and goal is minimizing the amount of payout for claims for damages on behalf of its clients, like BP. The information that Thad Allen was seeking in his letter to the BP CEO, Tony Hayward, was — would fail to get at this real critical point, which is BP is utterly motivated to pay as little as possible, which would obstruct the recovery of people in the Gulf region. And it would also obstruct the restoration of our communities and the lives of so many people who have lost their livelihoods for — into the indefinite future.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to also go to Amory Lovins. He’s at home in a very energy-efficient home, safely in Aspen in Colorado. He is the chief scientist and founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute.

You are known as one of the most influential thinkers on energy, alternative energy, in the world, Amory Lovins. What do you think needs to happen now?

AMORY LOVINS: Well, the President made two very interesting shifts in language in his speech. One is from just oil to talking about ending the addiction to fossil fuels, so that refers also to coal and ultimately, indeed, to natural gas. And second, he started a very interesting exercise in consensus building, because he pointed out that this has cost — our dependence on fossil fuel has cost not only to our economy but also to our national security and our environment. And I think that starts a new conversation of a new kind in energy policy, because we’ve always supposed people had to want the same things we wanted in energy for the same reasons. So if you had different priorities than somebody else, you couldn’t agree on the outcome. What the President started to do here is to say, let’s focus on outcomes, not motives, and then we can build a strong consensus. Whether you care most about national security or environment or economy, we ought to do the same things about energy. And if we do the things we agree about, then the things we don’t agree about become superfluous.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, talk about what we do need to do. There is very little discussion in this country about what it would mean to come off a fossil fuel economy, Amory Lovins.

AMORY LOVINS: Yeah. Well, at Rocky Mountain Institute our strategic focus is what we call reinventing fire, and that is mapping and driving the journey beyond fossil fuel, to transition from oil and coal, and ultimately gas, to efficiency and renewables.

There are many things that need to be done to bring that about, but the oil part is already clear, and we’ll publish an update of that. A lot has happened, and I say implementation is ahead of schedule, and the electricity part, in about a year. But six years ago, we did publish a road map for getting the US completely off oil by the 2040s at a cost roughly a fifth what we’re paying for the oil right now, not counting any of its environmental security or other hidden costs.

The two most powerful things we can do to get off fossil fuel, in policy terms — well, first is what we call “feebates.” That’s a very powerful way to get efficient cars on the road faster, and therefore induce manufacturers to offer a lot more of them. Feebates were adopted in France two years ago, and in the first year the sales of inefficient cars went down 42 percent and the sales of efficient cars went up 50 percent — a stunning result. And the way it works is, when you go to the dealer to buy a vehicle of the size you want, the less efficient models of that size have a fee attached to them according to how inefficient they are, and those fees are used to pay a rebate on the more efficient models in that size class. So we widen the price spread enough that people will look at the whole life cycle fuel saving, not just the first year or two.

By the way, there is another financial mechanism we could use for the low-income Americans who are having trouble affording efficient cars that they can afford to run. And we proposed a couple of ways six years ago for getting those families into very efficient, new, reliable, warranted cars that come with price-hedged gasoline and insurance all bundled in. And I think that is still on the table. And this would be a particularly good time to take a careful look at how to do it. This has huge social consequences. If, for example, the car ownership at that time were the same in African American and white households, the employment disparity would be cut about in half.

The other big policy thing we need to do that’s very powerful for saving electricity, that is half-made from coal, and saving natural gas is to reward utilities for cutting our bill, not for selling us more energy, which is still the case in about forty states. That’s just as dumb as it sounds. We’re rewarding the opposite of what we want. Oregon and California have a very good reform, called decoupling and shared savings. And to varying degrees, a couple of dozen other states have adopted or are adopting it. I think it ought to be considered nationwide, because once you align incentives between utilities and customers, it really transforms their culture and behavior. Most of the electricity we use is now wasted and can be saved — cheaper than just running an old coal-fired plant, even if the plant and the grid were free.

AMY GOODMAN: Amory Lovins, in a minute I’m going to ask you to take us on a kind of tour of your house to talk about how you built your house and how you’ve saved energy. But I want to turn now to Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club. His book is called Coming Clean: Breaking America’s Addiction to Oil and Coal.

Michael, assess President Obama’s speech, what the US is doing, what BP is doing, and what we need to do in the long run.

MICHAEL BRUNE: Sure. Well, the President’s speech wasn’t perfect, but it was quite good. You know, when you have someone — when you have the President talking from the Oval Office about how we won’t give up on this fight, that we need to hold BP accountable, that we need a trust fund of billions of dollars that will compensate the victims of this disaster, and that he is committed to this fight for the long haul, for years, that’s why we elected President Obama. The speech was not perfect. There was a lot that we needed to get from the President, more in terms of specifics and an ambitious goal. But it’s comforting to hear someone who is echoing the values of millions of people who want to see America move beyond our dependence on fossil fuels and are willing to organize and to fight for it. So that was good.

What we didn’t hear was the close, the closing argument. What we didn’t hear was a broad and ambitious and achievable goal by which we can get off oil, getting off oil in the next twenty years, where we can break our addiction to coal and we can transition to clean energy sources. What we also didn’t hear was what we all can do as Americans, how we can actually achieve these goals that the President began to speak so eloquently about.

Some of the things that we need to keep in mind are that we are fighting some of the richest companies in the history of the world. So, Amory Lovins’s policy suggestions are great. They’re fantastic. And the Sierra Club supports feebates. We’ve been working on decoupling legislation in states all around the country. But we have to remember that the coal industry isn’t just goingt to lie down and say, “OK, you won, all you clean energy activists, you.” And the oil industry isn’t simply going to give up. So we know the playbook —-

AMY GOODMAN: You know, I just want to say something.

MICHAEL BRUNE: —- for how the oil industry operates.

AMY GOODMAN: Watching the coverage yesterday on television, I’m seeing this new series of ads that are coming out from the coal industry, and it’s women wearing hardhats, one woman says she’s an environmentalist, and the reason she’s in coal mining is because she deeply believes in clean coal. And clearly, you know, this is a time it’s coming out as an alternative to the oil companies, right? To what’s happening in the Gulf of Mexico.

MICHAEL BRUNE: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: So put together coal — and of course we just experienced, before BP, the Massey coal mine collapse and explosion — coal with oil.

MICHAEL BRUNE: Sure. Well, first let me just say that this is part of the industry’s playbook, the oil industry’s playbook, whether it’s Exxon up in Alaska twenty years ago or Chevron down in Ecuador for the last twenty years. We know that the industry, what they try to do is they put a clean face on their operations, and they try to change the story.

But just as the coal and oil industries are integrated, so are our solutions, that our solutions are integrated at the same time. So, the way we need to get off oil, part of what Amory was suggesting was to electrify transportation by moving many of our cars and trucks, passenger vehicles, off of oil and onto the electrical grid. But then we need to clean the grid. We need to make sure that we’re chasing out all of the remaining fossil fuels, the tiny bit of oil that’s still used to produce electricity, the massive amounts of coal that’s used to produce electricity, and then eventually we need to transition off of natural gas at the same time.

The way that we do that is by first looking at all of the systemic challenges to a clean energy future. We need to separate oil and state, and make sure that the federal government isn’t subsidizing the dirty industries that we want to phase ourselves out of. We need to go to Wall Street, to the biggest banks in the world, companies like Citigroup and Bank of America, and make sure that they’re not — our consumer dollars aren’t financing our dependence on fossil fuels.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about the bailed-out banks, in addition —-

MICHAEL BRUNE: And then, finally, state by state -—

AMY GOODMAN: You’re talking about the bailed-out banks, so it’s not just consumer dollars invested in these banks, but it’s the US —-

MICHAEL BRUNE: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —- taxpayer having bailed these banks out, can actually set the rules, if President Obama decided that.

MICHAEL BRUNE: That’s right. That’s right. So if you’re a taxpayer, you’re paying for our fossil fuel addiction three different ways. You’re paying for it because of the taxpayer dollars that have gone to bail out banks. You’re paying for it through taxpayer subsidies to oil companies and coal companies. But then you’re also paying for it with your ATM fees, your home mortgage payments, your student loans. All of the fees that you’re paying to banks are then recycled back into the economy. And for every one dollar that these banks are funding clean energy projects, they’re putting twenty dollars towards dirty energy projects. So, as consumers and as taxpayers, we need to seize control of the situation and redirect our funding, whether it’s public dollars or private dollars. We have to stop funding the problem and start funding the solution.

AMY GOODMAN: Monique Harden, when we were traveling through the Gulf a week or two ago, you have the fishermen, you have the oyster shuckers, shrimpers, and you have the oil industry, the consultants for the oil companies. I went to a seafood festival, where they were mainly oil folks that were there. And when I was saying, “So do you think offshore drilling should end?” they said no, of course, because they know nothing else. I was talking to a Chevron consultant. He said, “This is the only thing I know,” which is why conversion is so important. Can you talk about this whole issue of, here you have a devastated coast, the bayous, the coastal towns of Louisiana, and yet people are still for offshore drilling, and how you think that could change?

MONIQUE HARDEN: Well, I think the —- my state of Louisiana, and our neighbors in the Gulf region, is really the belly of the beast, when you’re talking about this clean energy future. Going back to the 1920s, when little-known companies like Esso, of course Exxon now, and the Royal Dutch Shell Company came to our state, they there were given huge tax breaks that extend to this day that allows them to, and gives them incentive to, increase and expand their amount of pollution and facility base in our communities throughout the region. I think what needs to be supported and strengthened is an understanding that, for us in the Gulf region, this is a generational issue, where there’s no alternative that’s visible. And so, the work that folks like Amory and others are doing is extremely important, but there needs to be a real focus in terms of raising awareness and educating people about what those alternatives can look like and how we can create opportunities around those alternatives.

Also, we need to be more mindful of the fact that, just as in the situation with the workers at the Massey mine company, they go to work knowing that this could be their last day. And that’s a real fundamental human rights issue, to know that because of the kind of work you’re in, because there are no alternatives, you can lose your life. And that’s a deal and a bargain that’s been set up in our states around the Gulf of Mexico, but also around the country, that should be unacceptable in this country, especially as we are looking towards and looking forward, with great optimism, towards a clean energy future, is that we’ve got to make sure that this is good for people as well as our environment. We can’t leave people out of the equation. And we also have to really be supportive of folks being able to make that transition in a way that makes sense economically for them, as well as puts them on a sustainable path for the future.

AMY GOODMAN: Amory Lovins, the reality of what it means to live off the grid or in a different kind of grid, there’s so little discussion in this country, that people don’t know where to begin. Why don’t we begin where you are right now: in your house? And is it Aspen, right in Aspen, Colorado? Tell us how you built your house.

AMORY LOVINS: No, actually, it’s that valley. It’s in Old Snowmass, Colorado, valley with more elk than people. And we’re at 7,100 feet up in the Rockies, where it can occasionally go to minus-47 F. You can get frost any day of the year. You can get thirty-nine days of continuous cloud in midwinter, so it’s not a reliably sunny place. And yet, just off to my right is a tropical jungle, where we’re ripening banana crops thirty-three through thirty-five with no heating system, because the house is so well insulated in passive solar design that it didn’t need one. And it was $1,100 cheaper upfront not to put one in. So I then reinvested that money in saving about 99 percent of the water heating energy and 90 percent of the electricity. If I didn’t make electricity with solar, my electric bill for 4,000 square feet would be five bucks a month. And all of the extra cost of that efficiency in 1983 paid for itself in the first ten months. Today’s technologies, which we’ve just retrofitted, are a lot better. And the key is what we call integrative design, so we get any benefits from each expenditure. The arch, for example, that holds up the middle of my house, does twelve different things, but I only pay for it once. And I can tell you, it’s really fun to sit there munching your tropical fruit while a blizzard’s outside and know that you’re not using any fossil fuel, you’re not stealing from your kids, you’re a net exporter of energy to the grid, and it had great economics.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, wait a second. When you say a “net exporter of energy to the grid,” explain what you mean.

AMORY LOVINS: I have solar panels on the roof that make more power than the building uses, so we actually run our meter backwards most of the year, and on average for the whole year. It’s really fun to watch your meter run backwards. And, in fact, we designed the new renovations the last few years specifically to take as much coal-fired power as possible off the grid. Now -—

AMY GOODMAN: And do you get paid — does the energy company pay you for that extra energy that you are creating?

AMORY LOVINS: Yeah. They only pay us half as much as they charge us for a unit of electricity, but it is nice to get the credit. And you can do that in about forty states now. It’s called net metering. Also, we’ve set up the solar power system so that the house works with or without the grid. The lights don’t flicker if the grid goes away or if the grid comes back. That’s called making it islandable, and that gives us a much greater sense of security in a rural area where storms and other events can wipe out the grid.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, that is key, is the government support for alternative energy. I mean, if you want to build in an alternative way, in a green way, it’s expensive, unless to get, for example, tax breaks. I mean, in New Orleans, when we were going through the coastal towns of Louisiana, I mean, in Grand Isle, everywhere, the idea that there isn’t solar panels everywhere is just astounding. Michael Brune, take us from there, in terms of how we break America’s addiction to oil and coal. What are the government programs that need to be set in place? There is this moment now where people are — have arrived, they see the crisis. But the question is, is there going to be the specific, concrete leadership? We didn’t hear much concrete last night from the Oval Office.

MICHAEL BRUNE: Not yet. And that’s why it’s now our turn to inspire the President and to challenge the President and to challenge Congress to deliver a clearer plan to break our addiction to oil and coal. You know, what we need is a combination of the individual actions, like what Amory has been doing for so many years — and Amory, you know, I’d love to live in your house and eat your bananas right now, and there millions of Americans who can start to make very similar investments in energy efficiency in their own homes or advocate for it in their own businesses or within their own towns — but then what we also need to do is we need to organize collectively, to create more systemic change, to allow for us to create more jobs, to cut pollution, and to increase energy security through statewide and nationwide policies.

To give a couple examples, in Louisiana right now, the state legislature is considering its first renewable energy standard. So it will be the first bill in the state of Louisiana that will actually accelerate the development of clean energy. And it doesn’t have enough support yet. It doesn’t have enough support yet to actually go through. It’s one of the lowest goals. It’s about — I think right now they’re talking about a twelve-and-a-half percent standard for clean energy in the state of Louisiana, and it still doesn’t have enough support in the state legislature. So people in the state of Louisiana and others can help to finance a clean energy campaign in the state and to accelerate the development in a state that needs it more than any other. Right now I think we have about twenty-seven or twenty-eight states around the country that have some standard to increase the pace of clean energy development. We should have all fifty. We should have a standard of going to 20 percent clean energy by 2020, 30 percent by 2025, and increase the pace by which we’re phasing out of coal, phasing out of oil, and increasing investments in both efficiency in solar and wind.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, President Obama —-

MICHAEL BRUNE: The other thing that we can be doing -—

AMY GOODMAN: — is not even at cutting offshore drilling at this point. I mean, you have the Atlantis oil rig that is actually — it dwarfs Deepwater Horizon. It’s run by BP and most — it has tremendous number of problems — whistleblowers from within over the years. Yet most people don’t even know it’s continuing in the Gulf of Mexico.

MICHAEL BRUNE: Yeah, you know, when you talk to campaigners about the challenge of transitioning to clean energy, the metaphor that a lot of people use is we have to turn the supertanker around. And, you know, right now, to turn the supertanker around, you have to crank the wheel. You’ve got to crank the wheel. And so, right now what we’re seeing is, you know, maybe the boat is turning around, but we’re seeing the Obama administration doing a couple different things. On the one hand, they talk about expanding offshore oil drilling, perpetuating our dependence on dirty energy. And on the other hand, the administration has made legitimate and very substantive investments in clean energy and are helping to reduce our dependence on oil by increasing vehicle efficiency. We need to stop doing all of these things that extend our dependence and increase the pace by which we’re investing in a clean energy.

The fact that anybody in Congress or in the White House would be advocating for an expansion of oil drilling, at a time when we’ve had the worst disaster in American history, worst environmental disaster in American history, when we’re poisoning an entire coastline, is an outrage. It’s ridiculous. But what we need to do is we need to find a way to cobble together the votes to give enough assurance that we can meet our continuing energy demands, which we can do, while also investing in a future that doesn’t put at risk both workers and the environment.

AMY GOODMAN: Yet, where is the call right now? Has the Sierra Club made a statement to end offshore oil drilling? Have you met with the President to say this is the moment to stop? He’s clearly going in another direction.

MICHAEL BRUNE: Yeah, absolutely. The Sierra Club has been warning for years. I’ve just been at the Sierra Club for three months. But the Sierra Club has been warning for years that offshore oil drilling is risky, it’s dirty, it’s dangerous, it can be deadly. And sadly, we were proven to be right. So we have called on Congress, and we’re working with senators on a permanent — a permanent — moratorium on the expansion of offshore oil drilling. We’ve met with White House officials, advocating for the same thing, a permanent moratorium on offshore drilling. We have sent letters. We’ve made phone calls. We’ve had meetings with the White House.

And at the same time, what we’re also calling for is a more comprehensive, bold plan to move beyond oil in the next twenty years. You can go to the Sierra Club website or go to a satellite site, letsmovebeyondoil.org, and find out how you can get involved and to call on the President to make a stronger, bolder, clear, unequivocal statement that we need to move beyond oil and coal in the next twenty years.

Over the last several years, the Sierra Club has been working to stop the construction of new coal-fired power plants. With a lot of grassroots partners around the country, we have defeated 129 new coal plants that have been proposed in just the last few years. Now our challenge is not just to slow the rate at which things get worse, but to create that ecological U-turn and start to shut the dirtiest, oldest coal plants down and replace them with clean energy. So, we have a plan to get off both oil and coal within this generation, but it’s going to take the help of millions of people to actually make it happen.

AMY GOODMAN: Michael Brune, I want to thank you for being with us, the new executive director of the Sierra Club. His book, Coming Clean: Breaking America’s Addiction to Oil and Coal. Monique, thanks for being with us from New Orleans, Monique Harden, attorney and co-director of Advocates for Environmental Human Rights. And Amory Lovins from Old Snowmass, co-founder, chair and chief scientist of the Rocky Mountain Institute in Colorado.

Media Options