Guests

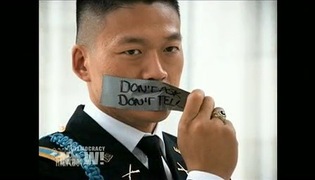

- Dan Choigraduate of West Point, an infantry platoon leader in the New York National Guard and a trained Arabic linguist who served in Iraq. He was discharged under the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for admitting he is gay.

“As we mark the end of America’s combat mission in Iraq,” President Barack Obama said this week, “a grateful America must pay tribute to all who served there.” He should have added “unless you’re gay,” because, despite his rhetoric, weeks earlier the commander-in-chief fired one of those Iraq vets: Lt. Dan Choi. Choi is a West Point graduate, an Arabic linguist and an Iraq war veteran. He was fired under the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. We talk to him about his life, his coming out and his military service. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In his speech before the Disabled American Veterans national convention in Atlanta Monday, President Obama paid tribute to the US soldiers who have served in Iraq.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: And as we mark the end of America’s combat mission in Iraq, a grateful America must pay tribute to all who served there. Remember, our nation has had vigorous debates about the Iraq war. There are patriots who supported going to war and patriots who opposed it, but there has never been any daylight between us when it comes to supporting the more than one million Americans in uniform who have served in Iraq.

AMY GOODMAN: President Obama might have added, “Unless you’re gay.” Today we speak with Lieutenant Dan Choi. He was just discharged under the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. Dan Choi is a graduate of West Point, an infantry platoon leader in the New York National Guard, a trained Arabic linguist who served in Iraq — exactly the kind of soldier Obama referred to in his speech. But Dan Choi was honorably discharged from the military two weeks ago for publicly admitting he’s gay. Choi has been one of the most vocal critics of the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. He came out on national television on The Rachel Maddow Show in March of 2009. He was dismissed by the Army in May of that year. Then, a few weeks ago, he received his final discharge papers.

At the Netroots Nation conference in Las Vegas last weekend, where thousands of bloggers, activists, journalists were, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid was forced to address Lieutenant Choi’s discharge after he was handed Choi’s West Point ring and discharge papers by the moderator, Joan McCarter, on stage.

JOAN McCARTER: This morning, Dan Choi gave me this to give to you. That’s his West Point ring. He says — he says it doesn’t mean what it did mean to him anymore. And this is his discharge. So, hopefully, you can take that with you.

SEN. HARRY REID: Well, let me just —-

JOAN McCARTER: You can use that, hopefully -—

SEN. HARRY REID: I just want to say, about the ring, my son, my youngest boy, played on three national championship teams at the University of Virginia, soccer champions, and he gave me one of those rings. And I love that ring. That was terrific. But I didn’t earn the ring. My son gave it to me. He earned this ring. And I’m going to give it back to him. I don’t need his ring to fulfill the promise that I made to him.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: It means nothing when [inaudible] —

JOAN McCARTER: Thank you.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: When it’s signed! When it’s signed!

JOAN McCARTER: When it’s signed, Senator. When it’s signed.

SEN. HARRY REID: OK, that’s good enough with me. When the bill is signed, I’ll keep it safely and give it back to him.

JOAN McCARTER: Senator?

SEN. HARRY REID: Hello, Dan. When we get it passed, you’ll take it back, right?

LT. DAN CHOI: I sure will, but I’m going to hold you accountable.

SEN. HARRY REID: OK, that’s good.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Dan Choi telling Senator Harry Reid on stage he’s going to hold him accountable for changing the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy. Then they hugged.

Well, I caught up with Lieutenant Dan Choi just before that event, earlier at the Netroots Nation conference, just after he had found out about his discharge from the military.

AMY GOODMAN: Lieutenant Dan Choi, welcome to Democracy Now!

LT. DAN CHOI: So great to be with you again.

AMY GOODMAN: What are you looking at?

LT. DAN CHOI: This is actually the email I got yesterday morning notifying me of my discharge orders. And this memo was actually sent to my dad, whom I am not speaking with right now. And I haven’t had any communication with him since October, so it was difficult to hear that they were using my dad as a conduit, saying that he signed for my paperwork.

It’s difficult when you come out all at once, to your parents and your church and your work, your colleagues and the Army and the government, and Amy Goodman. You know, it’s all very difficult, and it reminded me that I haven’t really done everything to hold my parents’ hand through this.

I started the journey because of my parents. And after Prop 8 passed in California, I felt I needed to something, as well, and I said I was just going to educate my parents about discrimination and about who I am and tell them the truth. And that’s how it all got started. I lived with them for six months, but it didn’t really go anywhere, and we left on very bad terms.

I decided to devote fully to the movement, to help build the movement, to help repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and full equality. And that took up my entire time, and I’ve not been able to tend to what my parents were also going through. And the fact that it went to my dad, and for three weeks, it sat — well, apparently, according to the Army, he signed for the papers and never notified me, never gave it to me, so…

AMY GOODMAN: How did you end up getting your discharge?

LT. DAN CHOI: Well, people were rumoring about it a day before and telling me that I’ve been discharged. “Why aren’t you coming out with it?” And I said, “Well, I haven’t gotten any papers yet.” So my commander gave me a call yesterday morning at about 10:30. I was right here, at Netroots Nation. I was not expecting to have to do this and deal with the discharge, but my commander, who’s been absolutely professional and absolutely sympathetic, as well as caring, on a personal level, throughout this entire journey, he said, “This isn’t news that you wanted to hear, for sure, but you are formally discharged, and I will forward you the memo.”

It was something I was expecting, but the pain and the emotion, you can never fully prepare yourself for that. Immediately when he said that, I thought about every moment of my service, from the time I was eighteen years old and I went to West Point and the friends that I made, the training, preparing for deployment, going to deployment, the Iraqi friends that I continue to contact and connect with and communicate with, all of the many things that I learned in my times in service, what that all meant, and especially this year of activism, I’ve learned a lot about what service really, really means and why we volunteer, to begin with, why we put others before ourselves.

And I have no resentment, I have no regret, to anybody in the military. This is clearly a failure of our government. We all know that America’s promises are not manifest yet, so long as gay or transgender people are getting kicked out of their workplaces, fired for telling the truth or expressing who they are. And that part of my commitment, that I learned my first days at West Point and from the early days growing up in my parents’ house, telling the truth and having integrity, never being ashamed of who you are, having that conviction that you are on the right path to helping other people, that oath and that foundation does not change. I might not have a uniform to wear, to drill anymore, and I might not have a commission anymore, but I still have a responsibility, I still have an obligation. It’s what we all signed up to do, to protect our Constitution. And I believe that with discrimination rampant right now against gay and transgender people, our Constitution is under attack.

AMY GOODMAN: How does it feel to be discharged in the midst of troops throughout the country being surveyed on changing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and President Obama himself expressing his desire to change this policy?

LT. DAN CHOI: I think it’s absolutely insulting that we’re having a survey right now, this day and age, that the commander-in-chief, who is the first racial minority to achieve that rank and that position — and it was a signifying moment for all of us, who — whether we’re racial minorities, whether we’re sexual minorities, whether we are American citizens or not even yet American citizens, it was an absolute moment of vindication for a lot of people that the first African American and interracial American is the president and the commander-in-chief. And the fact that we’re having a survey that hearkens back to the times of segregation and the times of absolute racism, that’s absolutely contrary to what our country stood for and continues to stand for, I think, is incredulous. And I honestly believe that future generations are going to look back at this time, and they will vomit. They will absolutely, with so much indignation, look at what we are doing and wonder why people didn’t stand up and shout at their government officials, what a travesty it is that we have not learned — seems like we haven’t learned anything, from the times when segregation laws and racism was just the thing to do.

The polls of our troops, it might not be unprecedented, but it’s un-American. It’s absolutely contrary to what our country and our military stands for that we would even ask the question, “Do you think discrimination is OK?” and that we would have to study that. I will give you the CliffsNotes version: you can read the Constitution, and you can see that discrimination is in no way in keeping with what America stands for. So when we’re talking about polling and asking opinions of soldiers, of servicemembers, nobody ever polls the soldiers on whether we should go to war or not. Nobody ever polls the soldiers on whether it’s going to be difficult for them. Nobody ever says, “What do you think about your commander-in-chief being African American?” Nobody ever polls in that way. And why should we ever poll when we’re talking about doing the right thing? It’s shameful that we’re actually asking the question.

AMY GOODMAN: Dan Choi, West Point graduate, Arabic linguist, Iraq war vet. He was just discharged under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” We’ll have more with him in a minute. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We return to my interview with the West Point graduate, Iraq war veteran, Dan Choi. He was just discharged from the military for admitting he’s gay.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you know what number you are — and I hate to put it like that, but where you stand in the number of gay men and lesbians and transgendered people who have been discharged from the military for your sexual orientation?

LT. DAN CHOI: Right now the estimate is at 14,000.

AMY GOODMAN: Since when?

LT. DAN CHOI: Since the beginnings of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 1993 and '4. We’ve seen so many hundreds that were just kicked out just last year, though, under President Obama’s watch. I don’t know what number I am, because those numbers are actually a very low estimate, and it does not include Reserve and National Guard soldiers, of which I am one. I am also an Arabic linguist. I’m qualified, but my job is an infantry officer, so I don’t even get counted in that statistic of those Arabic linguists, qualified Arabic translators and interpreters who are getting kicked out.

AMY GOODMAN: How do you feel that “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” began under a Democratic administration, and it continues under — you were discharged under a Democratic administration.

LT. DAN CHOI: Well, democracy doesn’t depend on one political party’s platform. Democracy depends on every one of us standing up to elected officials. Whether they have a D, an R, an I or a whatever after their name, they have an obligation to uphold and to defend and to support the Constitution. And when that doesn’t happen, we hold them accountable.

I think one thing that we learned from the civil rights movements, as well as a lot of the human progress movements throughout our history, of our civilizations, we need to remember that progress doesn’t depend on somebody else’s platform, and progress doesn’t depend on us just supporting the people who are in power. It is their job to enact and to manifest what America stood for and stands for. That's their obligation. It’s not my job, as a gay American, legally, among those American citizens who are oppressed, probably the most oppressed, legally, in America today — it’s not my job to help the President with his political aspirations and for him to keep his job. And for any Democrats who are here or who are listening — I’m sure we have a couple of them here — if you’re asking me to help you keep your job or your political career, I think you’re asking the wrong guy for sympathy, just about, today, at least.

AMY GOODMAN: Do we still call you Lieutenant Dan Choi?

LT. DAN CHOI: Well, you can. I am a former lieutenant. I’ve served, and I’m very proud of my service, and I’m very proud to continue serving. But, whether with a rank or with a title or not, whether with a pension or a paycheck or not, we still have an obligation. And honor and dignity does not come through titles, does not come through class or paycheck, wealth, or any of the other constructs of honor that we might think our society says is what honor is. It’s absolutely false to think that. Honor and dignity comes from our ability to stand up to what we know is right.

AMY GOODMAN: Dan Choi, you went to West Point at eighteen. How old are you now?

LT. DAN CHOI: I’m twenty-nine.

AMY GOODMAN: Eleven years you’ve served in the military. What made you decide a year ago to come out on national television?

LT. DAN CHOI: I came back from Iraq. And many times when I was sitting in the barricade areas within the compound or in my Humvee, I thought to myself, when am I going to get along with my life, get along with the truth, reconcile who I really am from what I’ve been pretending to be? And many times I would spend alone in Iraq, many nights I would be very contemplative. I came back from Iraq, and I decided that it’s not worth it. I could have died at any moment in the area that I was, in the Triangle of Death. Why should I be afraid of the truth of who I am?

I came out to my parents. I found love, and that was the reason why. It was difficult to come out to my parents. You know, with “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” sure, I could get kicked out, I knew that. I could give up a lot. And a lot of people have given up quite a hefty sum of benefits, including your medical benefits, your right to go to a VA hospital without paying, even if your disability rating is something like mine — I’m 50 percent disabled from my time in service. I stood to lose all of that, as well as scholarship moneys, a GI Bill and a home loan through the VA programs. And I realized that those were things that we could give up. That was nothing compared to the prospect of coming out to my dad, who’s a minister, and he’s affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention. He’s still in denial. He tells me, “Every single time you go on media, you must make sure that they know that I do not officially condone who you are. I do not officially love you for who you are. I cannot say that.” That’s his interpretation of what the Southern Baptists believe. And I wasn’t afraid of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in the military, in that regard; I was afraid of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” at home.

Coming out to them really allowed me to finally meet up with people who have also been through it, who have also served in the military, other West Point graduates. When we talked about our love relationships, we wondered why we were holding those back. I’ve wanted to go back to Iraq and to Afghanistan, but then I thought, if I die in Afghanistan or Iraq, then would my boyfriend be notified? Or would he have to hear about it through Democracy Now! or CNN? Who would be the one telling him? And the fact of the matter is, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” forces our families into the closet and into nonexistence. And that’s no way to support our troops or the families that allow them to continue to serve.

AMY GOODMAN: Dan Choi, what was your mother’s reaction?

LT. DAN CHOI: My mom, when I told her, she tried to express as much Christian love as she possibly could. I asked her, “If I tell you what’s going on, will you love me?” She grabbed my hand, and she said, “Of course. I will always love you.” And I said, “I’m gay.” And she grabs my hand even tighter and says, “I love you, but that doesn’t exist. It’s not in the Bible. It’s wrong. And I don’t know any gay people. I don’t know any gay people. I don’t any gay people.” And I’d asked her a month later, she said, “OK, I know one gay person.” And then she said — two months later, she said, “OK, I actually know a lot of gay people.” But she was in such denial. She said, “You can change. You can change.” And she voted for McCain, and she was a big Prop 8 supporter. And I was trying to explain to her, “The way you vote really does affect my rights and who I am as a human being, as your son, who wants to live a fulfilled life.” And she said, “Well, you can change. You can change. You can pray to God, and you can be straight.” She said that as long as I prayed to God enough, that I could just wake up in the morning and, you know, be straight, apparently. And I said, “No, I’ve tried. I’ve tried. I prayed all the time, at all of the retreats, all the revival services.” And she said, “But you can pray harder. Yes, you can! Like Obama! Yes, you can! You can change!”

And I — you know, in one way, I wanted to laugh and just say, “Well, you voted for McCain, and now all of a sudden you’re toting Obama slogans!” But in another way, I realized that it was so difficult to just hear that from her, that I can just change, and I haven’t been praying hard enough. I wanted to commit suicide many times when I was growing up. I didn’t know if I’d be able to live and tell my parents and know that I am a worthwhile human being. When I came back home, it got so difficult during that six-month period when I was coming out to them that I wanted to put a bullet into my West Point pistol and end my life.

One Sunday, I was wanting to do that, and I thought that there would be a hunting store that was open in Orange County. Before I did that, I went to a church for gay people, and I said, OK, well, I’ll try — because I was raised so religiously, I said, “Well, maybe I’ll hear what they have to say.” That was the first time I went to Metropolitan Community Church. And they were saying that “You are a child of God. You were created gay. You were born this way, and there is nothing that can separate you from God’s promise.” And that’s the first time I heard any of that put that way. I’ve been back and forth — atheism, agnosticism, humanism, born-again Christianity, back and forth. Because of this journey, I felt that I had to pick one or the other. You know, either you live honestly as a gay person, or you are a Chrisitan, but you cannot do both. And that was the first time that I heard that message, and it had a very powerful impact on me, as much as I felt that “I’m not an emotional person. I don’t really fall prey to some of those taglines, and I’m not just going to say that I’m converted just because I hear a 'Just As I Am' on the piano.” I didn’t feel that I was like that, but it had such a gripping, powerful force on me, that said, “You are a worthwhile human being.” And I felt that, at that moment, I was glad that I didn’t find a hunting store.

And to hear that kind of a message reminded me that, whatever your religion, you know, I think most Americans understand the story of Jesus and what that means to a lot of people and our psyche. When I read the verses of Jesus now, I see that he was a practitioner of civil disobedience of the highest regard and highest caliber, and for him, at a time when the religious establishment and the political power elites were telling him that he did not have a right to say the things that he was saying about himself or say the truths that he knew, or even say things like “I’m just fulfilling scripture. I’m just trying to manifest what promises you have given to your own people, through your own written words and your own written laws and legislation. I’m just trying to say, 'Why don't you make that true?’” And he was not treated very well by his government, as far as I remember, or the religious establishment, as far as I remember. So I’m not comparing myself to Jesus in any way, but I am saying that we can learn a lot from not only Jesus, but from Gandhi and from Dr. King and from the American Revolution and those military officers who were chastised for some of their tactics in bringing about real change, those who stood up. And the reason why we have America is because of people like that.

AMY GOODMAN: Did the other people in your unit in Iraq know that you were gay?

LT. DAN CHOI: In Iraq, no. I was very closeted throughout my entire service on active duty. I told one person as I was leaving active duty and joined the National Guard. You know, this is an infantry unit, so we’re going to talk about sex. And, you know, the bottom line is, it doesn’t scare soldiers. We go to drill and training, while I was serving in the National Guard. We go to infantry training. I’m in the bays, in the barracks, in the close quarters, in the forced intimacy. Three feet away from me is another bunk. I’m sleeping next to this straight guy, this infantryman. We were in the showers. We are naked in the showers.

And if that’s the fear, as you’re hearing the Pentagon say that we need to have shower curtains or separate facilities — you know, it sounds a lot like segregation, or “separate, but equal” mentalities, at least — I don’t think people realize how much that undercuts and insults our straight soldiers, to assume that they are so scared and so weak and so unable, so unprofessional, to deal with diverse people, after coming back from war, that they would quit because of gay people in their unit. I think it’s an insult to our soldiers to assume that they would be quitters. And for anybody to assume that and then to go on a slippery slope argument and say that we need the draft, because everybody’s going to quit, I don’t know of any more treacherous of a talking point than to say, “My assumption is that soldiers are quitters.” I think it’s an absolute slap in the face, not to me as a gay soldier, but to the straight soldiers, and I think those people who espouse that ideology should be ashamed.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the event President Obama had that you weren’t invited to.

LT. DAN CHOI: I wasn’t invited to a lot of events that President Obama has had over the tenure of his term in his office, but I wonder sometimes what good a cocktail party is to the building of a movement or to the achieving of our rights. That, in and of itself, does not achieve rights. In and of itself, sometimes it placates those who can be the greatest fighters. I was not invited to the White House either of the years during commemoration of Stonewall. Many people have said that the only reason why that event occurred in the first place was because gay people were cutting off funding from the Democrats, and so President Obama had to do something. And they put together this emergency cocktail party — because they think gay people just love to have those things and love to be invited, and we love to get dressed up and love to have martinis — declared a wonderful and eloquent and elegant proclamation. But in the end, those words did not give us our rights. And he is the most powerful, the most capable, some people would say most intelligent, man in America, to get to where he is. And the gay people that were in that room, many of them were just as intelligent and just as deserving of the opportunities that he’s had. But because of the legal discrimination, because of the legislation that hasn’t been passed, and because the President hasn’t been pushing, because he believes that calling on gay leaders to have a drink with him will make everybody equal, I think there’s something missing when events like that occur. And I don’t care to be invited to those events, as long as there is work to be done outside of the White House. If we’re not equal in our house, I don’t care about an invitation to his house.

AMY GOODMAN: Dan Choi, if the law was changed and you were able to return to Iraq or Afghanistan, how would you feel about the war then?

LT. DAN CHOI: Well, my feelings on the war and my responsibility to speak out against unjust wars and illegal wars and immoral wars, that certainly wouldn’t change. But, as a soldier, there are certain responsibilities, particularly in war. You put all of the politics of why you’re there aside, and you focus on accomplishing the mission in the most moral and the most, I think, effective way, so that you can get yourself, as well as your soldiers — and your soldiers first — alive back home.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Dan Choi, how does it feel to speak out so soon after you’ve just learned that you’ve been discharged from the military for being gay, for speaking out?

LT. DAN CHOI: It’s certainly painful, the process of getting kicked out. But being able to speak out for something greater than myself — clearly not for my career anymore — there is no greater dignity. There is no greater honor than to be able to do that.

AMY GOODMAN: Lieutenant Dan Choi, West Point graduate, Arabic linguist, Iraq war veteran, just discharged under “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” for admitting he’s gay. I spoke to him at the Netroots Nation conference in Las Vegas last week. Shortly after our conversation, he asked a moderator to give Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, the Nevada senator, his West Point graduation ring. Reid accepted it and said he would return it to Choi after Congress repeals “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

Media Options