Topics

Guests

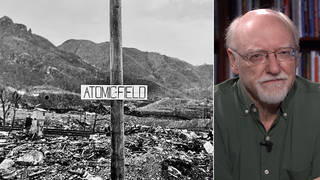

- Philip Whiteinternational liaison officer at the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center based in Tokyo, Japan.

Radiation at the shoreline of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power facility has measured several million times the legal limit, just four weeks after the earthquake and tsunami and days after workers discovered a crack where highly contaminated water was spilling directly into the Pacific Ocean. Experts say radiation dissipates quickly in the vast ocean, but they are unclear what will be the long-term effects of large amounts of contamination. The new levels prompted the Japanese government on Tuesday to create an acceptable radiation standard for fish for the first time. We’re joined by Philip White of the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center in Tokyo. “Cancers from this sort of level of radioactivity will not appear in the first few months or year; they will be late-onset phenomena,” White says. “So, it’ll require a lot of monitoring of health to actually see what the impact of this is.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Radiation at the shoreline of the Fukushima Daiichi plant has measured several million times the legal limit just four weeks after the earthquake and tsunami. The seawater was tested Monday before the plant’s operator began dumping more than 11,000 tons of low-level radioactive water, after it ran out of storage capacity for more highly contaminated water.

Over the weekend, plant workers discovered a crack where highly contaminated water was spilling directly into the Pacific Ocean. Japanese officials maintained Tuesday that the contamination still does not pose an immediate danger. Experts say radiation dissipates quickly in the vast ocean, but they’re unclear what will be the long-term effects of large amounts of contamination. No fishing is allowed near the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

The new levels, coupled with reports that radiation was building up in fish, prompted the Japanese government Tuesday to create an acceptable radiation standard for fish for the first time. Some fish caught Friday off Japan’s coastal waters would have exceeded the new provisional limit.

Japan says it will continue to update the International Atomic Energy Agency and other countries on the effects of the radioactive water. On Tuesday, Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano tried to assure neighboring countries.

YUKIO EDANO: [translated] We don’t believe that this current situation will have a direct effect on surrounding countries, but it does involve nuclear power, so there is a lot of interest. But there is a convention on early notification of a nuclear accident, and based on that, we are voluntarily offering information on the situation to the IAEA and to other countries.

AMY GOODMAN: Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano.

Russian media reports that Japan has asked Russia to send a floating radiation treatment plant, which will solidify contaminated liquid waste from the crippled facility. Engineers also plan to build two giant “silt curtains” made of polyester fabric in the sea to block the spread of more contamination from the plant.

Several thousand people have been forced from a 12-mile radius area near Fukushima Daiichi plant because of the radiation concerns. Tokyo Electric Power Company said today it would give affected towns about $240,000 each. So far, at least one town has refused to accept the money.

Meanwhile, the death toll from the earthquake and tsunami has risen to 12,341. More than 15,000 people remain missing. Another 160,00 are homeless.

For the latest update, we go to Japan. We’re joined in Tokyo by Philip White, international liaison officer at the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center in Tokyo, Japan.

Philip White, welcome to Democracy Now! Give us the latest on this contamination of the water.

PHILIP WHITE: Well, I think, during today and from last night, Tokyo Electric Power Company was releasing what they called low-level radioactive water into the sea. And the reason for doing that was because they needed to empty an area so that they could actually shift high-level radioactive water, which was already leaking into the sea, into this other space. They’re running out of space to hold all the radioactive water that’s flowing through the reactors and leaking out of the bottom. So, this was considered to be a less worse option.

Are you there?

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the millions — the radiation is millions of times the acceptable limit. What does this mean in the water, in the ocean?

PHILIP WHITE: Well, it depends how it spreads out, whether it goes off into the Pacific or whether it accumulates in pockets along the coastline. It will certainly have an effect on fishing. The fishing industry is already seriously damaged by this. But I think you’ve got to look at it as — it’s an ongoing thing. It’s not as if this one release solves the problem. Tokyo Electric Power Company says that this will have a very small — be a very small dose, represent a very small dose to people who continue to eat fish. But whether or not that is an accurate analysis, it’s not as if this is the end of the story. So, it’s a very serious situation, and it’s a long way before this is going to be brought under control.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the experts saying fixing the plant will now take months? What does that mean?

PHILIP WHITE: Well, I mean, it’s a gross underestimate. They won’t fix the plant. That’s the first thing. The plant will be abandoned. It’s a matter of whether or not they can actually bring it under some sort of control. And that “bring it under control” really involves taking away the heat from those radioactive spent fuel rods and the fuel rods that were in the plant. And they will be hot for years, decades, because that’s the way radioactivity works. It continues to send out energy, which takes the form of heat, for a long, long time. So, this notion of fixing it, I mean, it’s got no — makes no sense at all.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about the government setting its first radiation safety standards for fish today?

PHILIP WHITE: Well, they have set a number of standards for different food products and water, and these are all so-called provisional standards, and they are touting them at safe levels. However, you must realize that these so-called safe levels are actually emergency measures. They didn’t exist before. So these standards are based on the assumption that, “Well, we’ve got radioactivity out there; what are we going to do about it?” The levels are very high. If people continue to eat this sort of food for a long period of time, there’s a fairly strong probability that the rates of cancers will go up. But that’s a long-term issue. Cancers from this sort of level of radioactivity will not appear in the first few months or year; they will be late-onset phenomena. So, it’ll require a lot of monitoring of health to actually see what the impact of this is.

Media Options