Topics

Guests

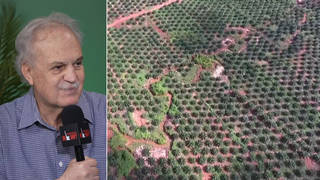

- Greg Melloco-founder and executive director of the Los Alamos Study Group. He joins us from the PBS station KNME in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

In New Mexico, an out-of-control wildfire that began Sunday has already burned nearly 80 square miles and is a mile or less from Los Alamos National Laboratory, home to a nuclear weapons plutonium facility. Pieces of ash from the fire have dropped onto the laboratory grounds, sparking “spot” fires. A senior investigator with the Project on Government Oversight said a fire at the facility would be a “disaster” that could result in large and lethal releases of radiation. Officials insist explosive materials on the laboratory’s grounds are safely stored in underground bunkers made of concrete and steel. But the group, Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety, told the Associated Press that the fire appeared to be about 3.5 miles from a dump site where as many as 30,000 55-gallon drums of plutonium-contaminated waste were stored in fabric tents above ground. The group said the drums were awaiting transport to a low-level radiation dump site in southern New Mexico. We speak with Greg Mello, the director of the Los Alamos Study Group, a citizen-led nuclear disarmament group based in New Mexico. “Los Alamos Lab is becoming the center of plutonium manufacture for the country,” Mello says, even though “it’s a place with a lot of natural hazards, not just fire, but also earthquakes.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: It’s been several months since catastrophic flooding from the tsunami in Japan knocked out cooling systems at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, resulting in three reactors melting down and producing the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. Now two U.S. nuclear plants are surrounded by rising floodwaters in Nebraska, and raging wildfires threaten to engulf a third nuclear facility in New Mexico.

Over the weekend, a floodwall protecting Nebraska’s Fort Calhoun Station nuclear plant from the overflowing Missouri River gave way. Water threatened the facility’s main power transformers, and power was cut off. Backup generators were used to cool the plant’s reactors and spent fuel pools. The plant is less than 20 miles away from Omaha, Nebraska’s largest city. About 85 miles downriver, the Cooper Nuclear Power Station could face a similar fate.

Meanwhile, in New Mexico an out-of-control wildfire that began Sunday has already burned nearly 80 square miles and is a mile or less from Los Alamos National Laboratory, home to a plutonium facility. Pieces of ash from the fire have dropped onto the laboratory grounds, sparking “spot” fires. Los Alamos Fire Chief Doug Tucker says he’s preparing for the worst.

DOUG TUCKER: The important part is I will not predict it’s not going to go in the lab. That’s one thing we cannot do, with the weather, with the wind, the topography, with the fuels. That said, we’ve done everything we can. It’s a layered approach, to where we build some buffers. But if it starts spotting—yesterday it was spotting a mile out. That well goes over our protective lands right now. And so, it’s a coordinated effort to where we use the weather, how can we use topography. We tried to reduce the fuel content going on the lab. We would—I will not say it is not going to go in the lab. We’re doing our best to keep it off the laboratory. If it spots on the lab, we get really aggressive about putting it out.

AMY GOODMAN: A senior investigator with the Project on Government Oversight said a fire at the laboratory’s plutonium facility would be a, quote, “disaster” that could result in large and lethal releases of radiation. Officials insist explosive materials on the laboratory’s grounds are safely stored in underground bunkers made of concrete and steel, but the group Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety told the Associated Press the fire appeared to be about three-and-a-half miles from a dump site where as many as 30,000 55-gallon drums of plutonium-contaminated waste were stored in fabric tents above ground. The group said the drums were awaiting transport to a low-level radiation dump site in southern New Mexico.

Well, for more, we’re going to New Mexico, where we’re joined by Greg Mello. He’s at the PBS station KNME in Albequerque. He’s director of the Los Alamos Study Group.

Greg, welcome to Democracy Now! Tell us more about the situation in Los Alamos and the significance of this nuclear facility.

GREG MELLO: Good morning, Amy.

The fire overnight burned to the north and to the west. It’s burning in the mountains on the west side of the Via Grande. It does not appear to have spread into the laboratory overnight. I’m sure there will be more reports as the morning goes on. It did spot into the laboratory in a place called Technical Area 49. And as was stated, it is about three miles from the main nuclear waste disposal site. It’s about four or five miles from the plutonium facility. Those areas aren’t particularly flammable, but one—in making assumptions of safety, one also has to assume that the fire equipment is not distracted by spot fires elsewhere or the wind doesn’t wheel around. So, at the moment, we don’t think—we don’t think it’s all that dangerous, but that assumes that Murphy’s Law is not too intense.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us what happens at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and why you’re concerned.

GREG MELLO: Well, Los Alamos National Laboratory is the—in funding terms, it’s the main nuclear warhead facility of the United States. There is a lot of plutonium there. There’s tritium—actually, tritium very close to the fire, about half a mile from the fire. Part of the problem is there’s an information deficit, and there’s a serious trust deficit. You can’t really take anything that the laboratory says at face value. It’s kind of a minimum—you know, they’d be the last to tell you if there was a serious problem. So you have to piece it together from other information. And that’s—Los Alamos Lab is becoming the center of plutonium manufacture for the country. And there’s about a $6 billion factory complex that’s being put together there in the center of the lab. It’s a place with a lot of natural hazards, not just fire, but also earthquakes. So, it’s a laboratory that’s in the process of becoming a manufacturing facility.

AMY GOODMAN: What about the concern expressed by Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety that say the fire now appears to be about three-and-a-half miles from this area where as many as 30,000 55-gallon drums of plutonium-contaminated waste are stored in fabric tents above ground?

GREG MELLO: Yes, those drums are definitely there. That’s about their distance to the fire. Without an external fuel source, those drums probably will be difficult to catch on fire. Some are flammable. Some are filled with cement paste. The fuel loading around that site is rather low. It’s not in a heavily forested area, just relatively small pinyon and juniper trees. Nearby, the area around the tents has been cleared. It’s on a mesa top. So, we’re not unduly concerned about that, but on the other hand, it’s very difficult to coordinate a lot of people in different agencies over a large area with issues of security, with issues of inter-agency communication. And so, there’s always the chance that there could be a major screw-up.

AMY GOODMAN: What about the large plutonium facility that Los Alamos is planning to build, with the purpose of building nuclear weapons?

GREG MELLO: Well, this is one of the centerpieces of the proposed Obama nuclear weapons build-up, or renaissance. Most people probably don’t know about that. In an effort to get the New START treaty ratified in the Senate, the White House made a lot of promises to Republicans, including building a new factory here at Los Alamos for plutonium warhead cores, called “pits.” That’s this $6 billion building in a complex of large—of other supporting facilities. There is a new factory of comparable size proposed in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which is moving along, as well. And there is a factory under construction in Kansas City. So, also Obama proposed—he’s not the first, of course—to replace the submarines, replace the bombers, replace some of the missiles, the cruise missiles particularly. Warheads are to be upgraded. All of this is very expensive. Whether it happens or not will depend on many factors.

AMY GOODMAN: [inaudible] nuclear renaissance under Obama, because we know, unlike his Republican predecessors, who did not start up nuclear—more nuclear power plants for decades, Republican and Democrats, he is pushing for this. That’s nuclear power plants. But you’re also saying a nuclear weapons renaissance under Obama. What do you mean?

GREG MELLO: Well, an unprecedented level of increased spending on new factories for nuclear weapons, on upgrades to existing nuclear weapons, changes to the stockpile. There’s a sense that if we don’t spend money—in the White House, there’s a sense that if we don’t spend a lot of money on these things, that we’ll somehow fall behind the Russians. It’s really like a mini Cold War—quiet, in the background, but there’s a lot of money involved.

AMY GOODMAN: How is President Obama justifying this with dealing with the deficit and everything else in this country?

GREG MELLO: Well, for the most part, he’s not having to do that. The Democrats are largely silent and supportive of Obama. Recently, the Republicans, of all people—in the House of Representatives, the Republicans in the House Appropriations Committee suggested that some of these projects were not cost-effective, that this particular project at Los Alamos, where they would bring what one administrator called the nation’s “storehouse of plutonium,” was premature and needed further study before it could be funded. So, the House Republicans tried to—are trying to cut back the Obama nuclear weapons renaissance, oddly enough.

AMY GOODMAN: Last question. Some have joked, Greg Mello, that if New Mexico were to secede from the United States, it would become the third-biggest nuclear weapons power in the world. Is this true?

GREG MELLO: Yes, it is, I’m afraid. It’s affected our politics, our culture. And we have more than probably 2,000 nuclear weapons a few miles from us here in the studio, and Los Alamos is a very large—becoming a very large manufacturing maquiladora. But perhaps we can stop that.

AMY GOODMAN: Greg Mello, I want to thank you for being with us, co-founder and executive director of the Los Alamos Study Group. He’s joining us from the PBS station KNME in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Media Options