Guests

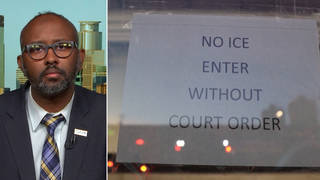

- Sharif Abdel Kouddousindependent journalist based in Cairo. He is a correspondent for Democracy Now! and a fellow at The Nation Institute. He is featured in the new HBO documentary, In Tahrir Square: 18 Days of Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution, airing on HBO2 at 8:00 p.m. EST on Jan. 25.

As tens of thousands of Egyptians gather in Tahrir Square to mark the first anniversary of the start of the revolution that ended Hosni Mubarak’s three-decade reign, we go to Cairo to speak with Democracy Now! correspondent Sharif Abdel Kouddous, who has reported on the popular uprising since it began. “What happened on January 25th was really an uprising that was 10 years in the making, a growing resistance movement to the Mubarak regime, to a regime that was characterized by a sprawling police apparatus that engaged in quashing of dissent and torture, a paralyzed body politic, and rampant corruption,” Kouddous says. “People speak about the barrier of fear being broken, but I really think it was a lack of hope. And that was the gift that Tunisia gave to Egypt: [it] was that here is the dream you can achieve, and here’s the hope that you can change, if you take to the streets.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We go directly to Cairo. Nermeen?

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Tens of thousands of Egyptians are gathering in Tahrir Square to mark the first anniversary of the start of the revolution that ended Hosni Mubarak’s three-decade reign. Inspired by the uprising in Tunisia, tens of thousands of Egyptians took to the streets on January 25th, 2011. Over the following 18 days, the protests grew across Egypt despite a violent crackdown.

While Mubarak resigned on February 11th, the uprising is an unfinished revolution for many Egyptians. The Egyptian military remains in control one year later. In the first seven months of military rule, nearly 12,000 civilians were tried in military courts—more than the total number during the past three decades under Mubarak.

On Tuesday, the military announced a partial lifting of Egypt’s emergency laws, which have been in place since 1981. Military leader Mohamed Hussein Tantawi made the announcement in a nationally televised address.

MOHAMED HUSSEIN TANTAWI: [translated] Now that the people has voiced its word and has chosen its members of parliament, I have taken the decision to end the state of emergency throughout the republic, except when facing crimes committed by thugs. This decision will take effect as of the 25th of January, 2012.

AMY GOODMAN: Ahmed Maher, one of the founders of the April 6 Youth Movement, says the protesters and the military have different visions of the revolution that began a year ago today.

AHMED MAHER: [translated] After the difference became clear concerning vision of the revolution’s meaning between the youth and the military ruling council, the youth seized this revolution as being about changing the regime, as being about freedom, dignity, social justice and changing the whole regime. But only the military council sees the revolution simply as preventing the inheritance of the throne by Mubarak’s son and keeping the regime as intact. Of course, that is not what we want. So the protests increased in March and April. The raids in Tahrir Square started, the torture of some activists and many injuries. There was also the killing of protesters.

AMY GOODMAN: Joining us now in Cairo, Egypt, in a studio overlooking Tahrir Square, is Democracy Now! correspondent Sharif Abdel Kouddous. He has covered the uprising for Democracy Now! for this entire last year, also now a fellow at The Nation Institute. In a moment, we’ll be joined by the HBO documentary makers who have just done a piece on—a documentary that will air tonight on Sharif covering the revolution.

Sharif, though, describe what you are seeing right now and where you are.

SHARIF ABDEL KOUDDOUS: Well, Amy, I’m standing just on the outskirts of Tahrir Square, the epicenter of the Egyptian revolution. And as you can see behind me, it’s an absolutely packed day, that one year after this revolution began, it still is very much continuing.

What happened on January 25th was really an uprising that was 10 years in the making, a growing resistance movement to the Mubarak regime, to a regime that was characterized by a sprawling police apparatus that engaged in quashing of dissent and torture, a paralyzed body politic, and rampant corruption. And that uprising ignited on January 25th. People speak about the barrier of fear being broken, but I really think it was a lack of hope. And that was the gift that Tunisia gave to Egypt, was that here is the dream you can achieve, and here’s the hope that you can change, if you take to the streets. And so, that’s what—that’s what happened. People had hope that they could cause change, and they started this revolution on January 25th, one that really reverberated across the world, one that changed the way, I think, many people think about themselves as citizens in a country and in participatory democracy. And that revolution succeeded 18 days later in toppling Mubarak.

But what happened on February 11th wasn’t the end of the revolution. It was really only the beginning, because, as you mentioned, the Supreme Council of Armed Forces took control of the country on February 11th, led by Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi, who was Mubarak’s loyal defense minister for 20 years. And what has happened over these past 12 months, as you can see behind me what’s happening now, is that the revolution has really progressed from this uprising against the Mubarak regime into a deeper struggle that is targeting the real backbone of modern autocracy in Egypt, which is the military, the regime that has ruled Egypt for the past 60 years, that enjoys a special political and economic autonomy outside of any kind of civilian control. And this is the regime that SCAF embodies. And so, the revolution has really become much more radical, I think, in targeting that aspect of Egyptian autocracy.

If you remember, right after the 18 days finished, the common chant in Tahrir was “The people and the army are one hand,” and the army was applauded for not firing on protesters, which is a dubious accolade in and of itself. But they enjoyed widespread popularity. And over the past 12 months, they’ve seen a real plummeting of authority, a plummeting of legitimacy, due to their really bumbling decision making over the course of the last 12 months in their transitional process, really erratic decision making, and a very—what’s been increasing crackdown on dissent, on protest and on the media. In the past three months alone, over a hundred people have been killed protesting, many of them in the square you see behind me. The bloodiest day of these past 12 months came at the hands of army soldiers, not of police. It was on October 9th, when army soldiers drove armored personnel carriers into a crowd of Coptic Christians and their supporters, killing 27 people in a single day.

So, while we’ve had this kind of crackdown and this more severe suppression of dissent, we’ve also seen growing resistance. So, as you mentioned, perhaps one of the most egregious things that the Supreme Council has done is put 12,000 civilians on military trial. These are really a big deterioration in basic due process rights. But perhaps the most successful grassroots campaign of 2011 was the “No to Military Trials” campaign. The practice has all but been abolished. An extra 2,000 people were just let go, who had been put on military trials today. We’ve also seen a burgeoning, growing independent media movement here that’s really blossoming and engaging in citizen journalism that is countering this clampdown on the media and countering a very vicious propaganda campaign by the SCAF. And so, what you’re seeing behind me is, I think, an embodiment of a revolution that is still going and still has a long way to go.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Sharif, can you say what the response in Egypt has been to Tantawi’s announcement yesterday of a partial lifting of the state of emergency?

SHARIF ABDEL KOUDDOUS: Well, that’s right. Tantawi went on the air yesterday and announced he would lift the state of emergency, but said except in cases of thuggery. So this is a very, very broad exception. Many protesters have been put on military trials over the past 12 months, being called thugs. So it gives them a broad—very broad leeway to exercise the law. It really reminds me of what Mubarak said in 2010 when he said he would only apply the emergency law in cases of terrorism or drug-related offenses. And, of course, as Human Rights Watch said in a statement, this really gives them the leeway to do whatever they want. I think it was seen largely as a way to try and quell the protests, to try and reduce their size, by giving some kind of concession. By releasing almost 2,000 prisoners who had been jailed in military trials, I think was a move, as well, to try and placate the crowd, and also the decision to have the first session of parliament happen two days before the anniversary of the revolution.

Of course, as we know, the Muslim Brotherhood is kingmaker in parliament, capturing about 47 percent of the seats. The ultra-conservative Salafi Nour party has about 25 percent. And a very distant third are an older liberal party called Wafd, and behind that, some of the newer liberal parties. But the parliament is seen as having wide legitimacy in Egypt. Many of the revolutionary youth boycotted the revolution—the elections, but it wasn’t a widespread boycott, by any means. The main charge of this parliament right now is to appoint a 100-member constituent assembly that will draft a constitution. Many people now, what they’re calling for, what they’re calling for in the streets, are for a quicker handover of power, saying that SCAF has—the Supreme Council has no right—no role anymore in the transitional process, now that we have an elected body. And so, they’re asking for a handover of power immediately.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re speaking to Democracy Now!'s Sharif Abdel Kouddous. He's overlooking Tahrir Square in Cairo. When we come back, we’ll continue this discussion and also talk about a new HBO documentary that covered Sharif covering Tahrir in the first 18 days of Egypt’s unfinished revolution. Stay with us.

Media Options