Guests

- Ana Nogueiraco-director of the new documentary, Roadmap to Apartheid. She was born in South Africa and now lives in the United States. Ana is a longtime journalist and former Democracy Now! producer, and a founding member of the New York City Independent Media Center and its newspaper, The Indypendent.

- Eron Davidsonco-director of the film, Roadmap to Apartheid, and a longtime media activist and filmmaker. He was born in Israel and now lives in the United States.

As the African National Congress voted Thursday to support the Palestinian call for boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel known as BDS, declaring it was “unapologetic in its view that the Palestinians are the victims and the oppressed in the conflict with Israel,” we look at a new film that examines the apartheid analogy commonly used to describe the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “Roadmap to Apartheid” is narrated by Pulitzer Prize-winning Alice Walker and puts archival footage and interviews with South Africans alongside similar material that shows what life is like for Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and inside Israel. The documentary has just been released to the public after a year-long film festival run, where it won numerous awards. We are joined by its co-directors, South African-born Ana Nogueira and Israeli-born Eron Davidson, both longtime journalists. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: “Hamdulillah,” The Narcicyst featuring Shadia Mansour. In his YouTube posting about this song, The Narcycist wrote: “To say 'Hamdulillah' is to be grateful for

what one has. The images of the past decades have cast a veil on our identity as a people. We, as international brothers and sisters, are now witness to injustice in real time. We watch our Wars in HD. It is time for us to claim our faces back,” he says. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman with Juan González.

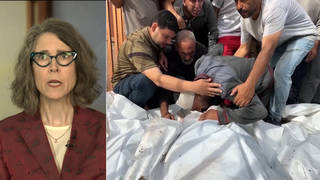

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, a new report says four Israeli attacks launched on journalists and media facilities during the bombardment of Gaza last month violated the laws of war by targeting civilians and civilian objects. Human Rights Watch issued the findings Thursday on the attacks that killed two Palestinian camera people, wounded at least 10 media workers and damaged four media offices. One strike also killed a two-year-old boy, Abdelrahman Naim, who lived across from a targeted building.

The report comes as the ruling party in South Africa has voted to support the Palestinian call for boycott, divestment and sanctions against Israel, known as BDS. On Thursday, the African National Congress declared it was, quote, “unapologetic in its view that the Palestinians are the victims and the oppressed in the conflict with Israel.” Several high-level South African church leaders recently visited Palestine and said they were shocked at what they saw. In August, South Africa’s deputy foreign minister, Ebrahim Ebrahim, issued an advisory not to travel to Israel, quote, “because of the treatment and policies of Israel towards the Palestinian people.”

AMY GOODMAN: Well, South Africans are no stranger to the complex issues facing Israelis and Palestinians. Now a new award-winning documentary examines the apartheid analogy commonly used to describe the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The film is narrated by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker. This an excerpt from the trailer for Roadmap to Apartheid.

ALICE WALKER: This is the beautiful land of Israel and Palestine. The world’s three most prominent religions—Islam, Christianity and Judaism—consider it holy land. Each year, millions of people from around the world come here to pray for peace and prosperity. Yet this land is also a major center of conflict in the world today.

For Jewish Israelis, the conflict centers on protecting a homeland created for the Jewish people in 1948. For Palestinians, it is about resisting decades of colonialism, expulsion, occupation and apartheid.

Most people identify apartheid with the grotesque system of control that existed in South Africa from 1948 to 1994, in which the white minority ruled over the black majority, stole their land, and deprived them of basic rights. It was a system reviled by the whole world, and it eventually crumbled under the combined pressure of internal resistance and international sanctions. Today, the word is back, and with it, too, is a growing global movement to end the Israeli form of apartheid.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from the trailer of Roadmap to Apartheid. The new film puts archival footage and interviews with South Africans, alongside similar material that shows what life is like for Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and inside Israel. Roadmap to Apartheid has just been released to the public after a year-long film festival run, where it’s won a number of awards.

For more, we’re pleased to be joined by its co-directors, Ana Nogueira and Eron Davidson. Eron is a longtime media activist, born in Israel, now living in the United States. Ana was born in South Africa, longtime journalist, former Democracy Now! producer, founding member of the New York City Independent Media Center and its newspaper, The Indypendent.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Ana, let’s begin with you, why you took on this project, this film.

ANA NOGUEIRA: Thanks, Amy. It’s good to be back in the studio.

Well, as you know, I was born in South Africa. And when I came to this country, I was only 11, but I was the youngest of seven children and learned about what apartheid was like through them and through research and looking into it. And then, when I started working at Democracy Now! in 2001, the Second Intifada had just begun, and so I was learning about the Israel-Palestine conflict through our daily coverage of the Second Intifada. And that’s where I began to pick up on the similarities with the apartheid analogy and the apartheid experience in South Africa. So, I thought it was important to really flush that out. And I met Eron, and he’s Israeli. We decided to do this project together and really present a thesis as to why the analogy is so powerful.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, it’s a very controversial analogy, Eron, and you come from South Africa, apartheid well known in this country and the struggle against it.

ERON DAVIDSON: From Israel. I was born in Israel. And yes, the analogy is very controversial—but getting more common now. In the past eight or so years, the analogy has been getting quite common, yet used somewhat rhetorically. And that’s why we wanted to make this film, is to kind of break down that carefully, where that analogy fits and where it doesn’t.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, I wanted to go to a clip from your film, which we first hear from the South African journalist, Na’eem Jeenah, and then Allister Sparks, a veteran apartheid-era journalist.

NA’EEM JEENAH: Now, in the South African context, the attempt by the apartheid government was to de-citizenize more than 80 percent of the South African population and then give them new citizenship in some kind of a fantasy entity—Bophuthatswana, Transkei, etc., so the South state could say, “You have no claims over us; you’re a citizen of Bophuthatswana. Social benefits, etc., is what you should be looking for there.”

ALLISTER SPARKS: The godfather of the system was Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd.

DR. HENDRIK VERWOERD: In South Africa, you can only achieve peace by separating the nations.

ALLISTER SPARKS: And he spelled out the whole bantustan concept. He said the black people have got to be given their own country. They embarked upon this remarkable experiment of trying to cut up the country into bantustans. And these were created, at least on paper, 10 of them, and the move began to advance them towards independence.

LUCAS MANGOPE: My government would like to continue as we are, an autonomous and independent country, preferably with extended borders, continued friendly and cordial relations with our neighbors, and, if possible, international recognition.

YASMIN SOOKA: Most of them were stooges and really puppets of the apartheid state.

ALLISTER SPARKS: To give some veneer of reality to the fantasy of the bantustans, the the Afrikaner government threw money at them, built elaborate parliaments, housing for ministers, built airports, sports stadiums. It was to create separate states. It was not so much a two-state solution as a multi-state solution.

When I look at Israel, when I traveled through the West Bank, I was looking at bantustans—totally unviable, impossible states. In many respects, it struck me as being significantly worse than apartheid.

NA’EEM JEENAH: Bantustans, as much as we abhorred them in South Africa, bantustan leaders actually had more power and more control than the Palestinian Authority has. What Oslo did was create an authority, which allowed Israel to still control the occupied Palestinian territory, but control it through a Palestinian authority. Ostensibly, there’s a Palestinian—some kind of Palestinian authority that’s controlling, that’s in power of the occupied territory. In fact, Israel controls the borders. Israel controls taxes. Israel controls all kinds of things—access in and out of that area.

ALLISTER SPARKS: To me, the big analogy was that South Africa, in taking these two choices, where you’ve got two or more nationalisms laying claim to the same country, you either have got to find a way to live together, or you’ve got to have a fair partition. The big similarity between apartheid South Africa and the Israeli-Palestinian situation is that both decided to have a partition solution, and, in both cases, it was a grotesquely unfair partition.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That was Allister Sparks, a veteran apartheid-era journalist, and then we also heard from South African journalist Na’eem Jeenah. The bantustans and the parallel in terms of what’s going on in the Palestinian territories today?

ANA NOGUEIRA: I think that’s one of the most important similarities to look at, because ultimately it shows where we’re going, where we’re heading with this. As the clip showed, you know, South Africa tried to set up a multi-state solution, to de-citizenize the majority population, put them into these ghettos or bantustans. And it failed. The whole world saw it for what it was and refused to recognize it.

Israel was one of the few countries who actually did recognize it, in an attempt to legitimize this strategy. Ariel Sharon apparently told one of the Italian former prime ministers that the bantustan solution was the situation for Israel and Palestine. And we’ve seen over the last 20 years that the attempt to create a two-state solution has failed, and Israel has done everything in its power to thwart that. Even the most recent U.N. recognition of Palestine as a non-member observer state, as soon as that was—you know, that referendum was held to the world and everyone supported it, Israel immediately showed everyone who’s boss by announcing the building of 3,000 settlements, withholding tax revenue from the Palestinian Authority, which cripples the Palestinian economy. So, this two-state solution really is a farce, and it really is more of a bantustan.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to a clip from Roadmap to Apartheid, when narrator Alice Walker explains part of the history of the Afrikaner movement.

ALICE WALKER: A deeply religious people, the white Afrikaners of South Africa believed they had a God-given right to a land that they considered mostly uninhabited. In what is known as the “Great Trek,” what Afrikaners consider their equivalent of the Exodus, thousands trekked into the wilderness in search of the promised land. The Afrikaners pushed into land the Africans considered theirs, and many battles ensued. Armed with guns and protected by a circle of covered wagons, known as a “laager,” the Afrikaners easily beat back the indigenous masses that outnumbered them.

This image of the heroic settlers in their laager fending off the savage masses became the dominant mythology in Afrikaner history, morphing into the philosophy of apartheid in 1948. Under apartheid law, the one standard against which everything was judged was the security of the state, and the state meant the Afrikaner people. With every law enacted, the freedoms of the majority were whittled away in order to protect the privileges of a white minority.

In Pretoria today stands a monument to the Great Trek, a shrine to this history and philosophy. A concrete laager, that iconic image of the Afrikaners’ military defense tactic, completely surrounds the monument—a physical representation of a state of mind that sees enemies everywhere and will do anything to protect against them.

AMY GOODMAN: That is a clip from Roadmap to Apartheid, narrated by Alice Walker. And I wanted to turn to another one, how you explore how Israel was one of the closest allies and biggest arms suppliers to South Africa’s former apartheid regime. This clip is narrated by journalist Ali Abunimah and Sasha Polakow-Suransky, author of The Unspoken Alliance.

ALI ABUNIMAH: The South African Defense Forces, as they were called, their army and navy was almost totally outfitted by Israel, because South Africa couldn’t get weapons from other countries. Israel was one of the only countries willing to break the arms embargo.

SASHA POLAKOW-SURANSKY: Well, the alliance started in earnest in 1973. By 1979, about 35 percent of Israel’s arms exports were going to South Africa, so they became a crucial client and also a crucial source for export revenue that Israel couldn’t give up easily. And it involved everything from tanks to aircraft, to ammunition, you name it. After ’77, there was a mandatory U.N. arms embargo. Israel violated the U.N. arms embargo openly, and many Israeli officials are happy to admit that. If you talk to South African defense officials, especially people from the air force, they tell you that Israel was an absolutely vital link and was a lifeline for them during the 1980s.

After 1977, the ideological component becomes much stronger. The top brass of the two militaries really felt that they were in a similar predicament and that they faced a common enemy. They also had a very similar conception of minority survival. There was a sense that Afrikaner nationalists were similar to Israelis, a beleaguered minority surrounded by a hostile majority.

AMY GOODMAN: That, a clip from Roadmap to Apartheid, Sasha Polakow-Suransky and, before that, Ali Abunimah. Eron Davidson, you were born in Israel. This is obviously an extremely sensitive comparison that many object to.

ERON DAVIDSON: It’s true. It is. It’s gaining more ground and becoming a more common discourse, though. And yeah, as you saw in the clip, the government ties through the '60s, ’70s and ’80s were extremely deep. They armed each other with nuclear weapons. The Israeli government did what's called “sanction busting.” Where South Africa couldn’t export products, it sent them to Israel; they manufactured them and then sent them out to the rest of the world, labeling it “made in Israel.” So—

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And now, obviously, the whole divestment movement is again another parallel in terms of what happened, in terms of resistance or worldwide resistance to the continuation of the oppression of the Palestinians, as it was in South Africa.

ANA NOGUEIRA: Yeah, there’s a very fast-growing global movement that is modeling itself on the anti-apartheid movement of the '80s and, you know, taking its cues from there, recognizing that apartheid ended as a result of internal resistance, as well, so there needs to be a Palestinian resistance, as well. But it was supported by this global movement that used boycott, divestment and sanctions to pressure the apartheid government to change its ways. And this recent ANC announcement that it's going to abide by this BDS call by the Palestinians is very heartwarming and probably going to have a domino effect in terms of more states getting onto this movement.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to a last clip from Roadmap to Apartheid. This is Eddie Makue with the South African Council of Churches. Later in the clip, we hear from Ali Abunimah and South African reporter Na’eem Jeenah.

EDDIE MAKUE: I have been able to visit Israel and Palestine on more than two occasions. And what I experienced there was such a crude reminder of a painful past in apartheid South Africa. We were largely controlled in the same way. The continuous checking at the roadblocks, and to see these young men and young women standing at the roadblock, having to perform the duties of a military junta, these parallels with Israel pained me severely while I was traveling through that lovely country.

ALI ABUNIMAH: The settlements are linked by modern superhighways, which are Jewish-only roads. Palestinians are not allowed to use them. And these superhighways crisscross across Palestinian land, linking the settlements together and linking them with Israeli cities inside the 1948 borders.

NA’EEM JEENAH: The separate roads that you find, the kind of whole settlement infrastructure that you find in the West Bank, for example, you know, which in South Africa we didn’t dream that we’d have roads that would be only for whites.

ALICE WALKER: In 2008, there were 800 kilometers of Jewish-only roads in the West Bank, or as the Israeli military prefers to call them, “sterile roads.” Settlers are issued yellow license plates so that the military can distinguish them from Palestinian drivers.

AMY GOODMAN: A clip of Roadmap to Apartheid. Ana Nogueira, the film is now out on DVD?

ANA NOGUEIRA: Yes, you can find the film on our Roadmap—on our website, roadmaptoapartheid.org, or on Journeyman Pictures’ website. There’s online and broadcast sales, too.

AMY GOODMAN: Ana Nogueira and Eron Davidson, I want to thank you so much for being with us, as we turn, in our last segment, to Reverend Billy. Stay with us.

Media Options