Since last year, 15 states have passed new voting laws that critics say suppress the votes of the poor, students and people of color. This is the topic of a major speech set for today by NAACP head Benjamin Jealous before the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva. The NAACP wants a U.N. delegation of experts to monitor the impact of voter identification laws, as well new restrictions on same-day registration, early voting, Sunday voting, and making it harder to run a voting registration drive. Its outreach to the United Nations has been compared to the group’s efforts in the 1940s and 1950s when it sought international support in its fight for civil rights and against lynching. Its visit to the United Nations also comes days after the group joined with thousands of people in Alabama to retrace the historic 1965 civil rights march in Selma. In what became known as “Bloody Sunday” on March 7, 1965, police attacked demonstrators at Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge as they tried to march for voting rights. Outrage over the crackdown led to passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: A delegation from the NAACP is—just arrived in Geneva to testify today before the United Nations Human Rights Council about restrictive voting laws in the United States. Since last year, 15 states have passed new voting laws that critics say suppress the votes of the poor, students and people of color. The NAACP is going to the United Nations, and this trip has been compared to the group’s efforts in the ’40s and ’50s, when it sought international support in its fight for civil rights and against lynching.

The NAACP’s visit to the U.N. also comes days after the group joined with thousands of people in Alabama to retrace the historic 1965 civil rights march in Selma. In what became known as “Bloody Sunday,” on March 7, 1965, police attacked demonstrators at Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge as they tried to march for voting rights. Outrage over the crackdown led to the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. This year’s commemorative march began at the Edmund Pettus Bridge and ended five days later, on Friday, in Montgomery, which the original marchers reached on their third attempt in 1965. As the NAACP and other groups commemorated this defining moment in the civil rights struggle this past week, they also rallied against Alabama’s new immigration law and its new voter identification law, which goes into effect in 2014. These are some of the voices from the march.

MARCHER 1: Up above my head—

MARCHERS: Up above my head—

MARCHER 1: Shout our voices in the air.

MARCHERS: Shout our voices in the air.

ELISEO MEDINA: We are here today to say we still believe in Dr. King’s dream.

UNIDENTIFIED: They are taking us back to a past that does not bear repeating.

MARCHER 1: I really do believe—

MARCHERS: I really do believe—

MARCHER 1: There’s a god somewhere

MARCHERS: There’s a god somewhere.

ARLENE HOLT BAKER: We are all under attack. If you are a worker in this country, you are under attack, because they’re trying to take our voices away and stop us from being able to bargain collectively.

MARCHERS: Oh, deep in my heart.

MARCHER 1: Oh, way down in my heart.

UNIDENTIFIED: When César Chávez was at the height of his fast, Dr. King wrote him, and he said, “Our struggles, our separate struggles, are really one.” And that is true back then, and that is true today. Let us be together. Let us march. And let us move ahead.

AMY GOODMAN: That video courtesy of the Service Employees International Union.

Well, NAACP’s CEO and president, Ben Jealous, is—was in Alabama for last week’s march. Now he’s in Geneva, about to address the United Nations Human Rights Council.

We welcome you to Democracy Now!, Ben. What are you going to be saying today?

BENJAMIN JEALOUS: Thank you, Amy.

We’re going to talk about the fact that more states have passed more laws pushing more citizens in our country out of the ballot box in the past 12 months than in—you know, than since the rise of Jim Crow. You have to go back to the 1890s to find a year when we passed more laws pushing more voters out of the ballot box than we have seen in the past 12 months, five million people pushed out, disproportionately black and brown. In Wisconsin, by some estimates, 75 percent of young black men don’t have an up-to-date, valid ID and will not be able to vote. You know, these laws have a horribly racially disproportional impact. And in the case of Florida, for instance, with—who just put back into place a bar on formerly incarcerated folks voting, that was the intent. It was very, very clear when that law was first passed in Florida decades ago, and when they put it back in place now, after—you know, with this new governor, they pushed off 500,000 people in that state by itself, half of those black people.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, go back to the ’40s and ’50s, why the NAACP testified before the U.N. now, and how you see this, more than a half-a-century later, is so critical to this issue that the NAACP has been raising for so many years.

BENJAMIN JEALOUS: So, yeah. So in—1947 was the last time that our staff led a delegation to the U.N. Human Rights—then called the Human Rights Commission, now Human Rights Council, in Geneva. It was W.E.B. Du Bois and Walter White. And they came here really to talk about the assault on voting rights in the U.S., which at that point had been going on for decades, the silencing of black people and how that frankly gave rise to and helped to continue a culture of racial violence and hatred and suppression of rights.

And so, we are here at this dawning of this period where, as you heard the protesters in Selma talking about, you know, a whole range of rights are being attacked in the U.S.: affirmative action; the right to organize; the right of migrants to this country to be treated in the way that, quite frankly, the Statue of Liberty itself suggests that they should be treated; you know, attacks on the rights of women. Against this backdrop, massive attack on voting rights. Why? Because when you come after people’s right to vote, which is the very right upon which their ability to defend rights that they may even hold more dear is leveraged, you make it easier to wipe away those other rights. So while no one is saying that they’re bringing back Jim Crow, they are trying to facilitate a more massive assault on rights by going after the right to vote.

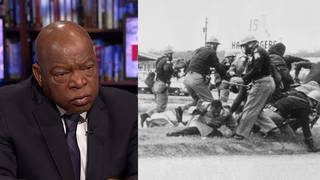

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to Democratic Congress Member John Lewis of Georgia. We had hoped he could join us today, but he’s preparing for the funeral of Don Payne of New Jersey, the only and—the only African-American Congress member from New Jersey. A veteran civil rights activist, Congress Member Lewis was among the original participants badly beaten on Bloody Sunday in 1965. And he, like you, Ben, was at the commemorative march this past week, as he has gone for many years. In a recent speech on the House floor, Congress Member Lewis reflected on the significance of Bloody Sunday.

REP. JOHN LEWIS: On March 7, 1965, 600 peaceful, nonviolent protesters attempted to march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capitol in Montgomery to dramatize to the world that people of color wanted to register to vote. We left Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church that morning on a sacred mission, prepared to defy the dictates of man to demonstrate the truth of a higher law. Ordinary citizens with extraordinary vision walked shoulder to shoulder, two by two, in a silent, peaceful protest against injustice in the American South.

We were met at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge by a sea of blue, Alabama state troopers. Some was on horseback, but all of them was armed with guns, tear gas and billy clubs. And beyond them were deputized citizens, who was waving any weapons they could find. Then we heard, “I am Agent John Cloud. This is an unlawful march. You cannot continue. You have three minutes to go home or return to your church.” We were preparing to kneel and pray when the major said, “Troopers, advance.” And the troopers came toward us, beating us and spraying tear gas.

That brutal confrontation became known as “Bloody Sunday.” It produced a sense of righteous indignation in the country and around the world that led this Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Eight days after Bloody Sunday, President Lyndon Johnson addressed a joint session of the Congress and made what I believe is the greatest statement any president has ever made on the importance of voting rights in America. He began by saying, “I speak tonight for the dignity of man and for the destiny of democracy.” He said, “At times, history and fate meet at a single time and a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.”

AMY GOODMAN: That was Congress Member John Lewis on the floor of the House. He was in Selma, Alabama, last week, as was Ben Jealous, our guest, head of the NAACP, right now in Geneva about to address the Human Rights Council. It’s 47 years after, well, what John Lewis described. What are you asking the U.N. Human Rights Council to do? What are your recommendations, Ben?

BENJAMIN JEALOUS: We’re asking them to take an interest in what’s happening in the U.S., to send over a delegation of experts, of lawyers, to, you know, look at what’s happening and to, frankly, make clear the horrible impact that these laws are having and the new ones will have.

We also want to make sure, quite frankly, that countries throughout the world cannot replicate these laws and pretend like they don’t know what they do. I mean, we saw, for instance, with the passage of the PATRIOT Act in the U.S., with its very vague definition of “terrorism,” that people like Hosni Mubarak, like Charles Taylor, held up that as justification for 20 years, 30 years of torture in their countries, saying, “If the U.S. says this is what torture is, then you know—then now you know why I’ve done what I’ve done” — sorry, “If the U.S. says this is what terrorism is, then now you know why I had to use those tactics against those people.” So, you know, any tear in the fabric of human rights protection in the U.S. becomes a gaping hole somewhere else. So we’re here, again, to ask the U.N. to come over and take an interest in what’s happening in the U.S., speak out against it, both for the protection of human rights in the U.S. and throughout the world, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: For those who say — and this is often repeated on the networks, on the talk shows — “What is the problem with someone having a photo ID, presenting a photo ID to vote?” what is the problem here, Ben Jealous?

BENJAMIN JEALOUS: First—yeah, so the first thing is that these new voter ID laws come in the midst of a massive onslaught against all sorts of voting protections. So they have attacked same-day registration, early voting, Sunday voting, made it harder to actually run a voter registration drive. And yes, they’ve also passed these voter ID bills, making it harder to vote. Every single one of those, quote-unquote, “reforms,” these voter suppression laws and tactics, have the same effect of driving down the black vote.

Now, with voter ID, the interesting thing here is this. First of all, those folks, they often lie and say, “Well, you need an ID to travel, so why shouldn’t you have an ID to vote?” Actually, you know, folks who say that should actually go online to tsa.gov, read the actual TSA regs. You are not required to have an ID to travel. You simply have to go through one more security screening. But, you know, frankly, I travel all the time. I’ve lost my wallet before. You can get on a plane without your ID. So they lie when they say that.

What they know is this. People who are too poor to own a car tend not to have a driver’s license—black people, brown people, disproportionately poor. So when you put in a financial barrier, whether it was the poll tax, you know, when they first put it in place 110 years ago or so, or it’s this requiring people to purchase an ID before they vote—and sometimes even if the ID is free, you have to show up with a copy of your birth certificate, and you end up paying for that—it disproportionately suppresses the black vote. Again, you know, people who are too poor to own a car, they tend not to have a driver’s license. People who are—you know, rent, they’re too poor to own a home, and they move frequently, like many renters in this country move every six to 12 months, they tend not to have an up-to-date driver’s license. If they’re students, their driver’s license tends to be from their home and not where they’re going to school. All of these intended to make it hard to vote.

And, Amy, you know, the reason we focus on the impact is because their expressed intent is so vacuous. I mean, they say, you know, “Oh, oh, oh, we’re doing this to present” — sorry, “We’re doing this to prevent voter fraud, voter impersonation.” And the reality is, in the entire country, according to various Republican governors, to the Republican Lawyers Association, maybe you get 25 cases of voter impersonation a year—out of tens of millions of ballots cast, 25 cases. And to prevent those 25 cases—again, and that’s being conservative and generous—they want to push five million people out of the ballot box. That’s not what we do in our country. We believe in one person, one vote. We believe in free and fair elections. This creates a situation that is neither free nor fair.

Media Options