Guests

- Abrahm Lustgartenan environmental reporter for ProPublica. He is the author of the book Run to Failure: BP and the Making of the Deepwater Horizon Disaster. His op-ed in Saturday’s New York Times, “A Stain That Won’t Wash Away,” calls for a criminal prosecution that holds BP individuals responsible for the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

- Dahr Jamailinvestigative journalist.

Links

- Dahr Jamail on Al Jazeera’s “Inside Story” about Gulf oil spill

- Follow Dahr Jamail on Twitter: @DahrJamail

- Read Abrahm Lustgarten’s reporting on Gulf oil spill at Pro Publica

- Follow Abrahm Lustgarten on Twitter: @Abrahm

- See 2 years of reports on BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in our archive

- Spewing 5,000 Barrels of Oil a Day, BP Spill Hits Louisiana Coastline (Democracy Now!, April 30, 2010)

- On Front Lines of BP Oil Spill: Democracy Now! Travels Across Coastal Louisiana (Democracy Now!, June 2, 2010)

- Roundtable: NOLA Environmental Attorney Monique Harden, Sierra Club Exec Director Michael Brune and Leading Scientist Amory Lovi

- Voices from the Gulf: "One Year Later, We’re in the Same Situation as Last Year" (Democracy Now!, April 20, 2011)

- List of whistleblowers who have spoken out about BP oil spill and clean-up

- BP to Pay $7.8B to Settle Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Lawsuit. Is it a Bad Deal for Gulf Residents? (Democracy Now!, March 5, 20

Two years since the worst offshore oil spill in U.S. history, we look at its impact on the Gulf of Mexico’s residents and wildlife even as no BP officials have faced criminal prosecution for the disaster. Eleven workers died when the Deepwater Horizon well exploded, and almost five million barrels of crude oil leaked into the ocean before the well was plugged after 51 days. BP maintains the Gulf is rapidly recovering thanks to the company’s efforts, but Al Jazeera reporter Dahr Jamail describes how scientists say shrimp, fish and crabs in the Gulf of Mexico have been deformed by oil and chemicals released during the spill cleanup effort. Meanwhile, ProPublica’s environmental reporter, Abrahm Lustgarten, says the company failed to learn from past mistakes that could have helped avoid the explosion. He is the author of the new book, “Run to Failure: BP and the Making of the Deepwater Horizon Disaster.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show with the second anniversary of the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. It was April 20th, 2010, when high pressure methane gas from a BP oil well in the Gulf of Mexico expanded onto the Deepwater Horizon oil rig. As the gas ignited, it engulfed the rig and caused it to explode, killing 11 workers on board, injuring 17 others. Before the well was plugged, more than 53,000 gallons of crude oil gushed into the Gulf each day for the next 51 days, nearly five million barrels in total.

The impact of the disaster continues to unfold for the area’s residents and wildlife. Scientists say shrimp, fish and crabs in the Gulf of Mexico have been deformed by chemicals released during the spill. One commercial fisherperson told Al Jazeera that half of shrimp caught during the last white shrimp season were eyeless.

SCOTT EUSTIS: We have some evidence of deformed shrimp, which is another developmental impact, so that shrimp’s grandmother was exposed to oil while the mother was developing, but it’s the grandchild of the shrimp that was exposed grows up with no eyes.

AMY GOODMAN: Others reported finding clawless and mutated crabs. A new report released this month shows a toxic blend of crude oil and a dispersant called Corexit is not degrading as some had hoped. The report also found the toxins penetrate wet human skin faster than dry skin and can be observed in skin under UV light. Nearly two million gallons of Corexit were used to disperse the oil, although it was later revealed the chemical made it more difficult for microbes to naturally digest oil.

Meanwhile, oil giant BP maintains the Gulf is rapidly recovering thanks to the company’s efforts. A video on the <a href=”“http://www.bp.com/extendedsectiongenericarticle.do?categoryId=9039957&contentId=7073053”>BP homepage features BP community outreach spokesperson Iris Cross explaining the company’s commitment to the region.

IRIS CROSS: When BP made a commitment to the Gulf, we knew it would take time, but we were determined to see it through. Today, while our work continues, I want to update you on the progress. BP has set aside $20 billion to fund economic and environmental recovery. We’re paying for all spill-related cleanup costs, and we’ve established a $500 million fund so independent scientists can study the Gulf’s wildlife and environment for 10 years. Thousands of environmental samples from across the Gulf have been analyzed by independent labs under the direction of the U.S. Coast Guard. I’m glad to report all beaches and waters are open for everyone to enjoy.

AMY GOODMAN: BP recently settled with victims of the spill for an estimated $7.8 billion over medical claims and economic losses in one of the largest class action settlements in history. Critics argue the settlement allows BP to avoid going to court, where more than 72 million pages of documents and hundreds of witnesses could reveal damning evidence.

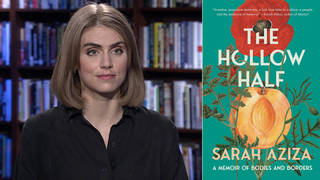

For more, we’re joined from Doha, Qatar, by investigative journalist Dahr Jamail. He has reported extensively on the BP oil spill for Al Jazeera. We’re also joined from San Francisco by Abrahm Lustgarten, environmental reporter for ProPublica, author of Run to Failure: BP and the Making of the Deepwater Horizon Disaster. His op-ed piece in the Saturday New York Times is called “A Stain That Won’t Wash Away,” calling for a criminal prosecution that holds BP individuals responsible for the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

Dahr Jamail, Abrahm Lustgarten, welcome to Democracy Now! I want to begin with Abrahm, about this issue of corporate responsibility and the fact that no corporate executive was charged. Talk about what they should have been charged with and how you see what you describe as, well, not really an accident occur two years ago.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, it’s not for me to say exactly what they should be charged with, but I’ve been looking at the history of BP, and they have a string of accidents over the last 15 years or so: you know, a refinery blast in 2005 that killed 15 workers, extensive oil spill on the North Slope of Alaska, and so forth. And in each of these cases, the company was charged with a crime as a corporate entity—two felonies, one misdemeanor. They eventually pled guilty to those crimes, but then we see accidents happening again, like in the Gulf of Mexico. The premise is that if an individual is charged, perhaps that would provide the kind of deterrent that would change the way that people inside the company think and might affect the decision making when it comes to the Gulf of Mexico.

What we saw in the Deepwater Horizon disaster was a string, one decision after another, eight or nine of them, that were—that seemed, from an observer standpoint, to be negligent, that really crossed the line of what was known to be best practices, crossed the line of better judgment, but all sped BP’s process along and moved the company towards profitability in that well faster.

AMY GOODMAN: Dahr Jamail, you’ve been following this BP oil spill since the beginning. Talk about what you have found.

DAHR JAMAIL: We have recently come across very, very disturbing information from Gulf region scientists. You know, the first person I came across was Dr. Jim Cowan with Louisiana State University, and he’s been working on a project, getting his funding from the state of Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. And he’s been, actually, for many decades, sampling red snapper, which is a very popular fish in the industry. And he’s been finding that before the BP disaster in April 2010, that of all the red snapper he was sampling, he was finding point-one-tenth [0.1] of 1 percent snapper coming up with lesions and other types of problems. Post-spill, that has gone to between 2 and 5 percent of all samples. That means an increase of between 2,000 and 5,000 percent, and in some areas as much as 20 percent, he said, in other areas who have extreme impact, where the oil and dispersants came in nearby the shore, of as many as 50 percent of fish sampled. Very, very disturbing information there.

And then, another doctor that I spoke with, Dr. Darryl Felder with University of Louisiana-Lafayette, he also has before-and-after samples. He was working out around the Macondo wellhead area on the sea floor with a grant from the National Science Foundation, that they wanted him to investigate just overall drilling impact on species in the area. And so, he had deep sea crab, deep sea lobster, deep sea shrimp, from before the spill, and then many, many sampling trips after the spill. And what he found was obviously a very, very large increase of finding crab and lobster, etc., that had black gills, that had appendages falling off, again similar stains on their shells, and again similar to findings not too different from Dr. Jim Cowan’s, in that when the oil, that much unnatural oil introduced into the environment, coupled with the dispersants, that it’s causing these lesions that are burrowing into the carapace and the shells and eating into the wax of the shells, causing an increase in the microbes that do eat oil. Not only are they not eating just oil, but eating into the shells, and then parasites and diseases and other illnesses are being formed.

And then, lastly and I think most disturbingly, as you already touched upon, the eyeless shrimp. We’re seeing very, very large incidence of eyeless shrimp now popping up not just in Louisiana, but in Alabama and Mississippi, not just inshore, but further far ashore—offshore. And some of the shrimp that we’re seeing, they came from a shrimper in Louisiana that was caught—caught 400 pounds of white shrimp in one catch in last September, just off the outskirts of Barataria Bay. And that was—of the 400 pounds of shrimp, the shrimpers told us that all of them were eyeless. So, very, very disturbing findings. And unfortunately, we’re expecting more to continue.

AMY GOODMAN: The BP website states, quote, “Did you know that seafood from the Gulf of Mexico is the most tested and inspected in the world? Inspectors from the FDA, NOAA, the EPA, and the National Fish & Wildlife Service patrol the docks on the Gulf regularly, testing and tagging fish and seafood. Fishermen from all along the coast want you to know that their catch is safe, plentiful and delicious,” unquote. The statement is accompanied by a video featuring Gulf Coast seafood catchers and vendors. This is a clip.

DEWEY DESTIN: The fish right now are the most inspected fish in the world. We’ve got about seven or eight agencies, from the FDA to NOAA to the Fish and Wildlife in Florida, DEP, which is the Department of Environmental Protection—they’re all inspecting these fish, and usually they’re up and down these docks all the time. So, from that standpoint, we can be as confident as you can be about the quality of the fish.

CHEF: This is a red grouper, pretty local fish. You can catch them off the Destin Bridge. See how pretty and white that is? A nice, pretty fillet of fish. Even after the oil spill, all of our fish look just like this—at least, you know, nice fish. And if there was ever any questions, then we would never even have, you know, brought it in in the first place.

AMY GOODMAN: And there’s this comment made on Al Jazeera by former Louisiana senator and current oil industry lobbyist J. Bennett Johnston. In this clip, he questions, Dahr Jamail, your findings and suggests shrimp industry is doing better than ever before.

J. BENNETT JOHNSTON: What NOAA has said is that there was damage to the dolphins before the spill, there’s damage after the spill, and they think there might be a connection between the spill and the dolphins, but it has not been established at all.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s former U.S. Senator Bennett Johnston, now an industry lobbyist. Dahr Jamail, your response?

DAHR JAMAIL: I think it’s pretty simple, actually. When we take the fact that 4.9 million barrels of Louisiana light sweet crude were introduced into the Gulf of Mexico and then almost two million gallons of toxic dispersants were injected into that crude oil both down at the source when it was gushing into the Gulf as well as spraying aerially for weeks on end after the disaster began, and you take that information, and then you look at regional scientists like Dr. Andrew Whitehead at LSU who’s released the killifish study, who we interviewed extensively, Dr. Darryl Felder at University of Louisiana-Lafayette, Dr. Jim Cowan at Louisiana State University, Dr. Samantha Joye over at University of Georgia who’s been studying the plumes in the deep—deep in the Gulf of Mexico, and then other studies that have been released by University of South Florida—all this information about oil persisting, dispersed oil persisting, seafood deformities, catches are down, seafood problems—and you take all this information and you compare that up against statements made by a giant oil company like BP that caused this in the first place, coupled with oil lobbyists, who do you want to believe?

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break, then come back to this discussion with Dahr Jamail. He’s speaking to us from Doha, Qatar, Al Jazeera investigative reporter, and Abrahm Lustgarten, environmental reporter for ProPublica. His new book is called Run to Failure: BP and the Making of the Deepwater Horizon Disaster. We’ll be back in 30 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: On this second anniversary of the BP oil explosion and disaster that led to 11 deaths, at least, 11 deaths of workers, and five million gallons of oil released, we’re joined in Doha, Qatar, from Al Jazeera’s studios by Dahr Jamail, who has been reporting extensively on the BP oil spill for Al Jazeera, and Abrahm Lustgarten is with us from San Francisco, author of a new book, Run to Failure: BP and the Making of the Deepwater Horizon Disaster.

Abrahm, you speak about the executives who led BP. You talk about—John Browne and Tony Hayward, among them—how they managed it, how this was a catastrophe that could have been avoided.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Yeah. I mean, when you go back 15 or 20 years, it seems like a really long time, but that’s where I found the roots of this story. And it started with John Browne, a former executive for BP, and his great ambitions to grow the company very quickly. He wanted to be the largest oil company in the world. He had a long way to go, and he did it by acquiring a number of companies, seven in all, tens of thousands of employees, and also aggressively cutting costs. And while he did that, cutting costs in all of his operations in maintenance and so forth, his employees, whether in Alaska or Texas or elsewhere, were consistently complaining that it was forcing them to cut corners, that critical equipment wasn’t being maintained, that there was a risk of oil spill or risk of death, and those complaints were often ignored. Sometimes the workers even received reprisals for making them.

And it took some years for the snowball to build, if you will, but by the early 2000s, BP really started having the kinds of troubles that its workers complained about. And John Browne kept pushing, in that sense, even while oil was spilling in Alaska or refineries were blowing up in Texas. And that plus the acquisitions of these other companies kind of led to an internal culture without clear lines of communication, with an ethos of “Do whatever it takes to please the upper management to make sure that the profits were there, no matter what happened.”

And there’s a lot about the spill of the Macondo well and the Deepwater Horizon explosion that fits that same pattern. A lot of the poor decisions can only really be seen in the context of the fact that they sped up the process for BP. And so, you know, Tony Hayward didn’t drive that—you know, that cultural transition in BP the same way that John Browne did. He made a lot of moves to try to correct it. He said, as he became CEO in 2007, that the company needed a cultural transformation. But it doesn’t appear, from the circumstances, that he was successful in achieving that in the years that he was CEO.

AMY GOODMAN: Abrahm, very quickly—you mentioned at the beginning of this conversation the two catastrophes before, but I don’t think people are very familiar with them—if you could explain once more what happened before BP’s oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico? This clearly wasn’t the first time.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Yeah, of course. The Texas City refinery, it’s on the Gulf Coast just outside of Galveston, Texas. It’s a sprawling plant, 1,200 acres, and it makes 3 percent of United States gasoline supply. It’s a very old, very outdated refinery. And at the time, there was some critical equipment that needed to be replaced. There was extensive discussion within BP about what the dangers were and how much it would cost to replace it. And at one point in 2004, the company, actually in London, received a report from the plant’s manager warning that workers were afraid to go to work. There was a document that said that the company might kill someone within the next 12 to 18 months if they didn’t replace equipment. BP emails that I obtained show that the company declined to invest $150,000 at the time to replace a piece of this equipment called a blowdown drum.

One day, the refinery operations were underway, and the fuel spilled out of the top of this tower that refines gasoline and should have been caught by this piece called the blowdown drum. It wasn’t. It sprayed into the sky and was caught by a spark, and it was a massive explosion, and 15 workers died. At the time, it was one of the largest industrial accidents in United States history. And it was followed up by many of the same things that we’ve seen after the Gulf spill: government investigations, internal BP investigations, extensive engineering reports, all finding—you know, as we’re now familiar with—a series of missteps, a series of poor decisions, and a real depth of cognizance on part of the company before the accident happened.

AMY GOODMAN: Going to the current catastrophe, BP’s claims fund is administered by Washington lawyer Kenneth Feinberg, who also handled a similar fund for victims of 9/11 attacks. Feinberg defended the amount paid by the fund so far.

KENNETH FEINBERG: There’s never been anything like this. Over a million claims in a year and a half? Compounding the volume problem, the quantification problem, is the qualitative problem: claims eligible from Mexico or Norway or Washington, D.C., or Boston; claims eligible when they’re filed not by fishermen or shrimpers or hotels, but by dentists, chiropractors, veterinarians—everybody, in good faith, blaming the spill for their damage.

AMY GOODMAN: Abrahm Lustgarten, what about the settlement? The documents are just coming out in the last few days.

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, there’s certainly reason to believe that in some cases the system has been abused. You could call BP a victim in some of those cases. It’s also quite positive that BP has invested the way it has both in cleanup and in restitution for victims in this way. You know, those are all important contributions that BP has made after this disaster. I do think they have to be seen in the context of the number—the amount of revenues and the $26 billion in profits that BP is also reporting in 2011, something that one of the EPA investigators who has worked with BP in the past described to me as just a cost of doing business at this point. But certainly BP is spending a very, very large amount of money on its settlements and on the restitution programs along the Gulf Coast.

AMY GOODMAN: Dahr Jamail, comment on the deal that has been struck.

DAHR JAMAIL: Well, more updated, Feinberg is on his way out, because so many people across the region are incensed at the way he’s handled most of the claims. And he claims that, OK, BP has paid out more than a million claims, is I think what he said. He doesn’t add, of course, that the vast majority of those claims are quick pay, meaning that they went across the coast, blanketed the coast with the—going up to people, filing individual claims, and said, “OK, an individual claim will pay you $5,000, and then that’s done, and you sign here and promise not to sue.” And so, that is the majority of those claims. If you had a business, it was $25,000 and a promise not to sue. The third option that BP gave people was: “We’ll see you in court.” And, of course, with the funding they have and the lawyers they have, that would be quite the feat.

So, you know, when you talk to the people across the Gulf Coast, you’re not going to find a lot of people that are really happy with the type of compensation and the claims that BP is giving out. I mean, I talked to Ryan Lambert, who heads one of the largest charter fishing businesses in the entire Southeast, and he said, “Hey, we’re going to court. They have destroyed my business. It’s not coming back. I haven’t seen one single speckled trout in three months. It’s the first time I’ve ever experienced that in my life. That’s 90 percent of the fish that we catch. So of course I’m going to go to court, because what they offered me, frankly, was insulting.” And I’ve heard that story from fishermen, shrimpers, seafood business owners, up and down the coast. The vast majority of the people I’ve spoken with down there are displeased, to put it very diplomatically, at the way that BP has handled compensation.

AMY GOODMAN: Also, interestingly, an organization that’s very much been in the news now, the nonprofit status of ALEC being challenged, the American Legislative Exchange Council, that’s pushed conservative legislation, partnering corporate executives with legislators around the United States at both the state and the national level—BP is a part of the American Legislative Exchange Council. While many corporations in the last few weeks have pulled out, from McDonald’s to Wendy’s to the Gates Foundation, BP is still there, along with other oil giants. And one of the laws that they are pushing through around the country are laws that—against dealing with global warming and that deal with limiting the Environmental Protection Agency. Dahr or Abrahm, can either of you comment on this?

ABRAHM LUSTGARTEN: Well, that would be an interesting turn, because one of the things that BP has said for many, many years—and this goes back to their former CEO John Browne, again—is that they acknowledge the importance of global warming and that they think that the oil industry, that the hydrocarbon industry, has a role to play in addressing it. I mean, this was one of the key things that made John Browne famous and one of the key things that led to the rebranding or was a product of the rebranding of BP as we know it. Changing from British Petroleum to this idea of “Beyond Petroleum” was this extraordinary acknowledgment of the impact of climate change. I haven’t heard a lot about BP being involved in lobbying against climate change, but that would be a really stark contrast with their previous positions. At worst, they have remained silent at times, but I haven’t seen them be actively against climate change efforts.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you both for being with us. Abrahm Lustgarten, environmental reporter with ProPublica, his latest book is called Run to Failure: BP and the Making of the Deepwater Horizon Disaster. And thanks so much to Dahr Jamail, who is joining us from Doha, Qatar, from the studios of Al Jazeera, has been reporting for Al Jazeera on the BP oil spill.

This is Democracy Now! We’re just taking a 15-second break, then part two of our national broadcast exclusive on the national surveillance state. Stay with us.

Media Options