Guests

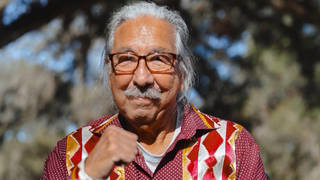

- Dalee Sambo Doroughan Inuit from Alaska, vice chairperson of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. She teaches political science at the University of Alaska-Anchorage.

Hundreds of indigenous leaders and activists from all across the world are gathering in New York City this week for the 11th session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. We speak with Dalee Sambo Dorough, an Inuit from Alaska who teaches political science at the University of Alaska-Anchorage and serves as vice chair of the Permanent Forum. Sambo Dorough discusses the range of hardships faced by indigenous peoples in Alaska today, from environmental devastation and threatened land ownership in the Arctic to rampant sexual violence. “In these various different political and economic agendas, indigenous peoples in the United States are at the bottom of the bottom. They always have been,” Sambo Dorough says. “The issues facing Alaska Native communities, indigenous communities across the United States, never appear on the radar screen as a priority issue.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We want to bring into the discussion, with James Anaya, Dalee Sambo Dorough, an Inuit from Alaska who teaches political science at the University of Alaska-Anchorage, one of hundreds of indigenous leaders and activists who have gathered here this week in New York at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. She is vice chair of the forum.

Dalee Sambo Dorough, welcome to Democracy Now! The significance of this meeting in New York and also of the recommendations that Professor Anaya is talking about, will be coming out in his report?

DALEE SAMBO DOROUGH: Mm-hmm, absolutely. Thank you very much for the invitation to share with you a little bit of information about the Permanent Forum. Absolutely, the fact that it’s the first country visit by the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples to the United States—I was fortunate enough to participate in his visit to Alaska. He spent just about 48 hours in Alaska—and as you can imagine, it’s a huge territory—and, unfortunately, didn’t have a chance to visit with all the major cultural groupings there, but I think that those who had a chance to engage with the special rapporteur were able to bring forward issues of relevance to all Alaska Native people.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I’d like to ask you—we had in the headlines this vote in Congress on the Violence Against Women Act. And data shows that rates of sexual assaults against Native American women are alarmingly high. In close to 90 percent of reported cases, the perpetrator is a non-Native man. I want to play a clip of a video produced by Amnesty International about rape in Alaska Native communities, featuring testimony from a woman named Louisa.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL: Across the United States of America, Native American and Alaska Native women are two-and-a-half times more likely to be raped. In fact, more than one in three of them will be raped in their lifetime. Even when women such as Louisa are able to report what happened to them, convictions are rare.

LOUISA: He got arrested for some other issue, and—and I assumed that he was arrested for my rape. But I found out that he got arrested for something else.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, the House votes to strip protections for Native women, as well as immigrants, from this—the Violence Against Women Act. And your sense of—your reaction to that?

DALEE SAMBO DOROUGH: Well, I think that this is just one example of denial of the real issues facing not only Alaska Natives, but Native Americans across the United States and indigenous women, in particular, not just in the U.S., but globally. The choice to remove funding from an urgent issue like this is just one example in a huge pile of examples as to a denial of the existence of real and serious issues.

With regard to violence against women, the tape that you ran and the statistics are absolutely dead on. The preying on marginalized and vulnerable indigenous individuals, and not just women, but young boys and girls and adolescents, is shocking and alarming. And I think that the Department of Justice, the United States government, rather than pulling funding, ought to be reinvigorating a discussion about the systemic racism that is faced not only out there on the streets that allow vulnerable individuals to become victims, but looking at the larger issues of systemic racism in the entire judicial system. Her reference to the perpetrator being arrested for something not directly related to the rape that she suffered is just one example. But if her case continued through the courts, you would likely, in all likelihood, in all probability, see evidence of systemic racism throughout the whole judicial system and her claim being dispensed with in a fashion that would be unjust and unfair and really reflects an inequality of treatment solely on the basis of race.

AMY GOODMAN: Who are the forces behind stripping Native American women, immigrant women, same-sex couples, the protections around fighting against domestic violence?

DALEE SAMBO DOROUGH: Rephrase the question. Who are they—

AMY GOODMAN: Who are the forces behind it? Who pushed for this in the House?

DALEE SAMBO DOROUGH: I’m unaware of who pushed for it. I’m sure that some of the rationale would, in fact, be that, oh, you know, every budget has to be cut; we have to, in the larger context of being frugal and in these particular times. It’s really—it’s really unclear to me. But I guess what I would also suggest is that in these various different political and economic agendas, indigenous peoples in the United States are at the bottom of the bottom. They always have been. The issues facing Alaska Native communities, indigenous communities across the United States, never appear on the radar screen as a priority issue.

AMY GOODMAN: What about the push for environmental resources in the Arctic, the entire—the international community going for your area of Alaska?

DALEE SAMBO DOROUGH: Yeah, thank you for raising that, because not only—not only the Inuit throughout the North Slope and northwest coast of Alaska, but Arctic indigenous peoples overall, are pressured in ways that we’ve never seen before. And I speak, in particular, of our neighbors, the Russian Federation. I was at a site event that was hosted by the Russian Federation yesterday, and their basic and essential message was that the Arctic, which is the traditional homeland of the indigenous peoples, the small nations of the Russian north, ever since, essentially, the sea level stabilized, they’re being—they’re being pressured. It was referred to by the Russian Federation as the heart of the energy security of the Russian Federation. I mean, they—and that’s huge. So, the rapid industrialization that their communities will face is just one example of the pressure that indigenous peoples are under. And this is in a context of serious outstanding claims and rights to lands, territories and resources.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, in December 2010, President Obama announced the United States would sign on to the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, following years of opposition. Obama spoke before tribal leaders at the White House.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: And as you know, in April we announced that we were reviewing our position on the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. And today, I can announce that the United States is lending its support to this declaration. The aspirations it affirms, including the respect for the institutions and rich cultures of native peoples, are one we must always seek to fulfill.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Can you talk briefly about the significance of President Obama’s announcement?

DALEE SAMBO DOROUGH: Well, the significance is, on the floor of the General Assembly, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—as referred to, the Kansas group—all four of those states voted against the declaration. So, the change in position, the review of the declaration, and the willingness for this administration to express its support for the declaration is highly significant. It’s a reversal of the position. But more importantly, and I think what’s more important about the statement that he gave, is that the actions, the actual implementation out there and on the ground to improve the quality of life of indigenous peoples, is what’s even more important. And I think that we, as indigenous peoples in the United States, need to continue pressing the U.S. government to implement in concrete and comprehensive ways.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you very much for being with us. Dalee Sambo Dorough is vice chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, also teaches political science at University of Alaska-Anchorage. And we want to thank James Anaya, U.N. special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, also professor of human rights at the University of Arizona College of Law. We look forward to seeing your report, and we’ll report on it again when it comes out.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. When we come back, part two of our conversation with Javier Sicilia, who is one of Mexico’s leading poets, has come to the United States to challenge the war on drugs. Stay with us.

Media Options