Related

Guests

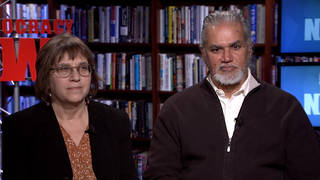

- Mariel Hemingwayactress and subject of the new documentary, Running from Crazy.

- Barbara Koppletwo-time Oscar-winning filmmaker whose documentaries include the 1977 classic, Harlan County U.S.A., and Running from Crazy.

The new documentary “Running from Crazy” chronicles the life of actress Mariel Hemingway, the granddaughter of the great novelist Ernest Hemingway. The film focuses on Mariel’s family history of mental illness and the suicides of seven relatives, including her grandfather and her sister, Margaux. The film is directed by the two-time Academy Award-winning filmmaker Barbara Kopple, whose documentary “Harlan County U.S.A.” has become a classic and won an Oscar in 1977. We’re joined by Mariel Hemingway and Barbara Kopple from the Sundance Film Festival in Utah. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to today’s interview. We’ve just returned from the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, where the new documentary Running from Crazy premiered. The film chronicles the life of actress and model Mariel Hemingway, the granddaughter of the great novelist Ernest Hemingway. The film focuses on Mariel’s family’s history of mental illness and suicides of seven relatives, including her sister Margaux, the supermodel, and her grandfather Ernest. In the film, Mariel opens up about how she put her own depression and suicidal thoughts behind her.

The film is directed by two-time Oscar-winning filmmaker Barbara Kopple. The first film she ever made alone, Harlan County U.S.A., has become a classic and won an Oscar in 1977. I sat down with Barbara Kopple and Mariel Hemingway last week at the Sundance Film Festival.

But first, let’s go back to 1954, an excerpt of the late, great writer Ernest Hemingway’s speech accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY: No writer who knows the great writers who did not receive the prize can accept it other than with humility. There is no need to list these writers. Everyone here may make his own list according to his knowledge and his conscience.

It would be impossible for me to ask the ambassador of my country to read a speech in which a writer said all of the things which are in his heart. Things may not be immediately discernible in what a man writes, and in this sometimes he is fortunate; but eventually they are quite clear, and by these and the degree of alchemy that he possesses, he will endure or be forgotten.

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness, but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness, and often his work deteriorates, for he does his work alone, and if he is a good enough writer, he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day. For a true writer, each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment.

AMY GOODMAN: That was the acclaimed writer Ernest Hemingway accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954. He committed suicide July 2nd, 1961, in Ketchum, Idaho. His granddaughter Mariel was born just a few months later. At the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, just a few days ago, I interviewed Barbara Kopple, the Oscar-winning filmmaker, and Mariel Hemingway about the title of the new film, Running from Crazy.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: That would be me. I jokingly sort of have said, for years, “Ahhh, I’m running from crazy!” I’ve been running from crazy my whole life. And yeah, so the—I said it in an interview, and they went, “Oh, what a great title!” I was like, “Oh.”

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean by “running from crazy”?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Well, you know, my—as the documentary sort of points out, that, you know, the family has—there’s generations of suicide and mental illness and all that stuff, that’s unspoken. But my sister, my oldest sister, who’s in the film, Muffet, has suffered from mental illness since I was a child, so that was always looming. That was always there. Tremendous amount of addiction in the family, knowing about the many different suicides—you know, uncle who suffered from mental illness, getting—you know, they had shock treatment, the whole nine yards. And so, I was always a little—not a little, a lot fearful of waking up one day and being crazy, or thought maybe I am crazy and I just don’t know it, you know. So, for me, my whole life was about surviving crazy. It was really. But my role was different than my sisters. My sisters sort of did it as—you know, they were rebellious and partiers and, you know, had addictive behavior. Mine was addictive, but on the other side, sort of towards health and wellness, although I didn’t quite do all the right things when I was younger. But I always went outside. I always felt like I was trying to get away from the feeling of losing it. And a lot of my early childhood was all about controlling everything.

AMY GOODMAN: When did you understand about your family history? When did you learn about your grandfather, Ernest Hemingway, who he was and how he died?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: I think I knew that he had killed himself. It wasn’t spoken a lot about in my home. My dad didn’t talk about it a lot. I didn’t know where he had done it. I knew that it happened in Sun Valley. I knew that there was mental illness, but I didn’t really even understand what that was. I mean, as a kid, you sort of don’t—you think your family is normal, even if they’re yelling and screaming and there’s a lot of dysfunction in the home. You know, I thought that that was my normal—that was normal for me. Really understanding it has been a process over many years, to be quite honest. I think the more—and even this film coming to fruition has been a completion of understanding. You know, I understand myself a lot better even through watching it. I’m like, “Wow! Now I see why I made the choices that I made.”

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to turn to a clip in the film, Running from Crazy, where you’re in your grandfather’s house.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: I always avoided right in here. This is where he killed himself. I was in my late twenties when I found out. I never knew. And somebody said, “Well, yes, this is where it happened.” And I was like, “Whoa.” I was so blown away. I just had no idea that this was it. But I would not come in here as a kid—totally freaked me out. Felt like a basement, you know, like a creepy basement that you don’t want to go into. And, of course, it was just kind of the back door to the outside. But it’s like something kept me away.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Mariel Hemingway walking around a back-door area of her grandfather’s house. Talk about your sister. Talk about Margaux. She is a central figure in the film, not to mention in your life.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And in this complicated story of addiction and of depression, mental illness, suicide.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Well, Margaux—you know, it—what I love about the film is that it’s made me have compassion for her and understand her in a different kind of way, which I never did as a kid. I mean, she was seven years older than me, and, you know, when you’re a child, seven years is a big jump. It’s different when you’re an adult, but she was practically out of the house by the time I had real memories. And her coming back and her life was just odd to me. She just—she got me a role in a movie called Lipstick, which really started my career, which was—created a lot of tension, because I got notoriety for it, and she got slammed. And there were just things about our relationship that were very, very difficult. And because I was always making choices towards health, or what I thought was health, I was very judgmental of how she was living her life, like I didn’t understand why she drank so much. I didn’t understand her partying. But that was her getting out of pain. I just couldn’t see that, because I was too young. I was—you know.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to a clip of the film, Running from Crazy, where Margaux is actually making a film about your grandfather.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Actually, before we go to it, explain what it is she’s doing here.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: She had decided—and Barbara found this amazing footage. You know, that was what was the—before we go to that, I have to say that that was the most amazing part that Barbara kept a secret from me. She didn’t tell me she had footage of my family and my sister. I had no idea that she had made a documentary. I mean, I had heard that she had made one, or that was making one or something. She found this footage. She found 43 hours of, you know, unseen footage of my sister. But it shows my family in the kitchen and things that I had said to Barbara, sort of thinking I was imagining it almost, because they’re my memories, and she found footage, and it matches. It was so chilling for me to actually see my mother, you know, on the counter with her feet in the sink and in the yellow—yellow and baby blue kitchen, you know? I mean, it was crazy.

BARBARA KOPPLE: Yeah, and for us, it was a treasure to find it.

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you find it, Barbara?

BARBARA KOPPLE: Our sound man, when we went to Ketchum to film for the first time, said—

AMY GOODMAN: This is in Idaho, where Mariel grew up.

BARBARA KOPPLE: This is, yeah, Sun Valley, Idaho. And he said, “You know, in the ’80s, I shot a film with Margaux.” And I said, “Where? Where is it?” And he said, “Well, you could try calling this person, this person.” And we got on it, but—and it was a two-hour or one-hour film. And then we found a place that had 43 hours that had never been seen before, never looked at. And, you know, we—

AMY GOODMAN: And Mariel, you had never seen it?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: I had never seen it. I didn’t know it existed. So, literally, telling her stories about my childhood, she had—yeah, she had—not—it wasn’t my childhood, but she had footage of that house and the behavior. It was crazy.

BARBARA KOPPLE: And for me, it was bringing a whole different layer to the film. And as Mariel spoke about the film, we were actually seeing the real things that happened and the things that she felt, and it was also sort of stepping into Margaux’s life and seeing her interview her father and Ernest Hemingway’s oldest son. I mean, it was just miraculous for her. It would be—every time I would go on a shoot, I would run back, and I would look at more footage to see: What can we substantiate? What can we try to start to put together?

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Margaux changed the spelling of her name from the sort of more regular M-A-R-G-O-T—

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —to?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: M-A-R-G-A-U-X, which she says that my parents had a romantic interlude in Paris over a bottle of Chateau Margaux. I think that was a made-up story, but, you know, it worked for—

AMY GOODMAN: Where they conceived her.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yes. I think it worked. It was more—it was more mysterious. It was a better—it was a better story than M-A-R-G-O-T.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to a clip of the film, where you describe your mother and father, your nightly ritual. We’ll put it that way.

BYRA LOUISE HEMINGWAY: Drink the wine.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: My mother and father drank wine every night, and they called it “wine time” — always my favorite. And wine time started about 5:00, and my mother would sit on the countertop in the kitchen, and her feet were like crossed in the sink—every night, same place. You know, they’d have one glass of wine, and things were kind of happy, and they were actually having a regular conversation.

BYRA LOUISE HEMINGWAY: Do you want me to do that?

JACK HEMINGWAY: No, I’m fine.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: But after a couple glasses of wine and the alcohol kicked in, nastiness would happen, uncomfortable—I can’t remember why it would start, but there would—some switch would happen. Somebody’s thrown a bottle against the wall, somebody gets cut. My mother would storm off to her bedroom, and my dad would go down into the basement, where he lived in his land of seclusion. And I would clean up the dinner party, the blood, the glass. It’s just a—just weird, like it was the most normal thing to do, like that’s what you did.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Mariel Hemingway describing growing up in her family house. You say in that clip, Mariel, you thought this was standard, that the little girl in the family, the child, would clean up for her parents every night.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Absolutely. Yeah, I mean—and I really did. I thought—because that was the role that I played. You know, they were all kind of drink—I never drank. I’ve never drunk. You know, based on watching this, “wine time” really kind of was a—it had a double—you know, it had double—it was double-sided. You know, it started out OK. One drink’s good. Two drinks is OK. Three drinks gets a little funky. And then four drinks, people are mad, and nobody can talk. And then they have gourmet dinners on TV trays in front of Jeopardy, because nobody can communicate anymore. So, it was—it was just a double-edged sword. And I was the girl that decided—and I played the martyr my whole life, you know, who was going to clean up and be good, so that would be the way that I got attention and the way that I was loved, you know.

BARBARA KOPPLE: And she also, too, would never—nobody in the family would ever say that there was any trouble, because they were all “good WASPs,” and so—

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Right.

BARBARA KOPPLE: —they kept it inside.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, here is Margaux not exactly keeping it inside, but standing outside her grandfather’s house, Ernest Hemingway’s house, talking about what went on there. This is Margaux making her own documentary.

MARGAUX HEMINGWAY: This is my grandfather’s house. He spent a lot of time there writing. And, of course, that’s where he took his life. I’ve always felt that if somebody can’t go on living and creating the way they can, I mean, the way they’re used to, and in a healthy form, in which grandpapa was accustomed to, I mean, I accept the fact that he—that he killed himself.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Margaux Hemingway as a young person making a documentary about her famous grandfather, Ernest Hemingway, talking about suicide—

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —his choice in ending his life.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yeah. It’s a—that’s a chilling moment, because it’s so prophetic, you know. I mean, like, I remember watching it when you showed me the—you know, what, a month ago, when I saw it for the first time. And it’s just so—you know, it takes your breath away, because you know what’s happening, and you know what’s going to—you know what’s to come. And it—and her acceptance of suicide being a choice for my grandfather, it’s that moment that you just go, “Wow! That’s powerful.” And I think, for me, who’s been running from crazy my whole life, to realize that that’s not a choice for me, even though I’ve had suicidal thoughts in the past, wow, it was so clear that that’s just—it’s not acceptable in my life, you know, which was a wonderful kind of realization.

BARBARA KOPPLE: And also, too, Margaux idolized the thought of Ernest Hemingway.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yes.

BARBARA KOPPLE: You know, hunting, fishing, drinking, women, bullfights. And so, that was her ideal, and she felt that she was a lot like him. And that’s why she wanted to retrace his footsteps.

AMY GOODMAN: The horror with the kind of metaphor you have in the film of the bullfight in Pamplona and this bull being skewered, dying, the bleeding, and there is Margaux weeping, looking at the bull, comparing the bull and the dying bull to—

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: To her life.

AMY GOODMAN: —her own life.

BARBARA KOPPLE: To her own life, to her pain, and just attributing it in such a close way that you could really see her going down.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go back to Margaux in this documentary, where she’s interviewing her and, Mariel, your father, Jack Hemingway, also a writer, the son of Ernest Hemingway.

MARGAUX HEMINGWAY: This is a question that everybody wants to hear.

JACK HEMINGWAY: Not me.

MARGAUX HEMINGWAY: Is it really just so hard being—growing up being grandpa—I mean, Ernest Hemingway’s son?

JACK HEMINGWAY: I wasn’t very conscious of it, you know, as a kid.

MARGAUX HEMINGWAY: That’s the one thing growing up here. I mean, you never, ever, ever had us, you know, read grandpapa’s—I never, ever felt like—I never even knew who Ernest Hemingway was, I mean. How do you feel about all of us, your daughters, being so well known?

JACK HEMINGWAY: I know that the kind of lives that you’ve—that you’ve chosen are tough on you, because, I mean, I saw what effect fame had on papa, both in a positive and negative way. You know, I think—it seemed to me I heard you or Mariel, or both of you, at some point said, “Don’t worry, Daddy, I’ll never change.” But you do. And, you know, you have the whole world open to you. You’ve had opportunities as a result of your grandfather’s fame, which have given you chances that some little gal off the street would not have had.

AMY GOODMAN: There’s Margaux Hemingway interviewing her father, Jack Hemingway, talking to him about what it’s like to be the son of a famous man and for him to have these daughters, Mariel and Margaux, who are also so famous.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: He was a great—I mean, he was a great outdoorsman, my father, and he was tying a fly, and he was speaking to my sister, as you can see, you know, answering her questions about what it’s like to be the father of famous daughters and the son of a famous man. And I think, although he chuckles and acts like it’s OK and that it’s alright and, you know, that he accepts that, there’s a pain in him. And you can see it in that moment. You can see how there’s a feeling of, like, not—of a lack of completion or something, like he didn’t quite do what he wanted to do. I always felt that my dad was just on the verge of something that he couldn’t quite complete for himself, because he was a wonderful writer in his own right, but, you know, how do you do that?

AMY GOODMAN: You have very complicated feelings about your father, and in the film you raise the issue of incest.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Right. I bring it up because I think it informs how—how you see my sisters and why they—they turned out the way that they turned out. That said, I loved my father, still love my father. He was a wonderful man. I learned so much about the outdoors from him. I—you know, I really did care for him. It’s complicated, because—and I think it’s one of the issues that is important for other people to see, because I think we all come from families, and we all have complicated relationships. He was a—you know, he drank too much. And in our childhood, he drank a lot. I’m not even sure that he remembered any of that, you know? I’m—and probably not at all. So, I didn’t—that’s the hardest part of the documentary for me to talk about, because I never want to throw my dad, whom I love, under the bus. But it’s the truth. And one of the things that I’ve discussed before is that I made a pact with myself to tell the truth. I wasn’t going to—if I was going to do this, I was going to go all out and really do it and dig deep and not—not cover things up. I felt that it was honoring of the piece, an honoring of the story. And I still don’t think my dad’s a bad guy, at all.

AMY GOODMAN: Did he—

BARBARA KOPPLE: And she really did. I mean, she—our first cut was five-and-a-half hours, and it was so hard to cut it down. And it went to five-and-a-half hours, then to three-and-a-half hours, and we just felt like we were ripping the innards out of this film. So, she gave up everything, maybe even more than I needed to know.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Mariel, that is one of the, I would say, most painful part of the film, when you seemed to be retrieving these memories of—did he victimize all of his daughters?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: No, not that I’m aware of. I don’t have any kind of memory myself, though my—you know, and I said it in the film, I slept with my mother since I was like seven years old. Granted, she had cancer, and I was her primary caregiver. I had slept in the same room to take care of her, but I also think that I was being protected, at some level.

AMY GOODMAN: That your mother was protecting you.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yeah, I think that it was unknown, you know, and I don’t think this was like conscious thought that I’m going to—I think it was like an unconscious way of protecting me.

AMY GOODMAN: Actress Mariel Hemingway and director Barbara Kopple. We’ll talk more about their film, Running from Crazy, in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue our conversation in Park City, Utah, at the Sundance Film Festival with Mariel Hemingway and filmmaker Barbara Kopple, director of the new film Running from Crazy. I asked Mariel about the legacy of her grandfather Ernest Hemingway and her sister Margaux, who once claimed she didn’t even know who her grandfather was.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: The odd thing is, is that that was—that was a hard one, actually, to believe, because she modeled her life after my grandfather. But maybe as a child she didn’t know. But as she went out into the world and became a model, and she was traveling in Paris and—you know, and she was going to—

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, she was a supermodel.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: She was. She was the biggest. You know, she talks about that Time magazine thing. I mean, no model had ever been on the cover of Time magazine. And she was—you know, she was the first model to be paid several million dollars, you know, back when that just didn’t happen. It was new. So, then she started to—I think she—in my mind, it was a misinterpretation of someone’s life, you know? It’s doing all the things that my grandfather did, but without doing the other, without doing the creative part, without—he was doing it for a reason, to—I mean, I’m not saying that that—it was actually the most functional, but it’s how he got himself to write. And I think that there was always that missing piece in her. It’s like I’m doing all this, but where is the outlet? Where’s the creative? Where—you know what I mean? So, it’s an interesting—I don’t know—conflict.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how do you deal with this with your daughters? How do you talk about your family? How do you raise them differently?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: You know, I think the best thing that you can do is to be clear and honest. But I wasn’t initially. When they were young, I didn’t talk about that, because I didn’t want that to be something they feared like I had feared. And maybe that was a mistake. Maybe I should have said more. I mean, this has been a very transformative sort of journey, just seeing the film with my—with Langley. For her to understand—I mean, she was it just days ago and said, “Wow!” You know, she had such a great—number one, great insight, powerful insight on the family, but also just so much compassion. And I think it was really nice to have your daughter see you and see what you’ve been through, but without putting it on her. She could decide whether she was going to take it, but she decides that’s not her. And I think that my journey, with all the crazy things that I’ve done in order to find no crazy, have broken that chain. So I don’t feel like I’m handing it to them.

BARBARA KOPPLE: Also, her Langley is very intuitive towards Mariel, because on the Suicide Walk, the American Foundation to Prevent Suicide, Mariel gave a speech, and it was a very hard one to give. And she introduced people who had lost people that they loved. And Langley just felt she was having a hard time getting through it, that it was emotional, and you see her put her hand on the center of her mother’s back to center her. And it was just so beautiful and so loving. And then, after it was over, Mariel puts her arms around Langley and just said, “That was so hard.” And you just feel the bond, and you feel the closeness between them, of really having each other’s back.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re recovering your whole life, but what you are doing.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Well, that’s what’s so beautiful, and thank you for asking, because the truth is, I really feel like this whole movie and being able to look at the past in order—it’s really just information that’s led me to right now. I mean, I have—you know, I have this company called the WillingWay, which is with my partner, Bobby Williams, who’s in the film, who’s our comic relief in the film. And that’s really—it’s about health and wellness and lifestyle and how—how you think, what you eat. You know, how you put yourself out in the world really can inform your mental wellness, mental, physical and spiritual wellness, actually. And that’s really become my life.

And, you know, for—I love that scene, because I didn’t know that they had filmed her doing that. But I love the fact that I could see her seeing me differently, like she didn’t know me to be happy a lot. I mean, I had happy moments, but I was generally just a little bit down, a little bit depressed. And now I’m so happy, and it’s because of the lifestyle choices I make. And that’s—if there’s anything that I want to have come out of this film, it’s that it’s not a “Oh, poor me” film about me. It’s about everybody. Everybody has different choices that they can make. I mean, you may not make my choices, but you can certainly make better, healthier choices that actually can help to make your life more balanced, more healthy, more happy and joyous.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to you and Bobby in Running from Crazy. They’re taking a journey, a road trip.

BOBBY WILLIAMS: We’re going to Ketchum and Sun Valley. We’re leaving in five. We’re actually going to travel 2,000 miles in four days.

BOONE SPEED: This looks really good, Bob. We’re in Red Rocks shooting a—this is a piece with Mariel Hemingway and Bobby Williams. It’s a holistic—it’s a piece on holistic living and living harmoniously with the world and in the environment.

BOBBY WILLIAMS: Up towards the sky would be easy.

BOONE SPEED: Looks amazing.

BOBBY WILLIAMS: That’s good.

Whenever we do road trips together, I want to stop constantly. “Let’s put our feet in the water. Let’s do this. Let’s do this. We need to do this.” For my whole life, it was always about, you know, just doing whatever’s in front of you.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: And that’s such a great for me to have learned, because my life was about—

BOBBY WILLIAMS: Pleasing, being on time.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Pleasing, being on time, schedule, doing what I needed to do.

BOBBY WILLIAMS: Doing what you need to do, directors, yeah, long days.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yeah.

BOBBY WILLIAMS: The definition of “adventure” is not knowing what’s going to happen next.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Mariel and Bobby on the road, taking a, what, four-day trip, thousands of miles, and just going on, as he puts it, an adventure.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yes. And we—we do road trips often. And this particular road trip was to do a little film, a little short film about the WillingWay and how we live our lives, and we’re—we have fun, and we go on—you know, and what we eat, and we climb—you know, we rock climb and do all this stuff. We get into—you know, we have a regular relationship, and we fight. And what’s so great about it—I mean, it wasn’t great in the moment—I will have to tell you that; I was a little pissed. And I was really mad that there was a camera on.

BARBARA KOPPLE: But that’s good for you.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: But it was great for me.

BARBARA KOPPLE: Yes.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: And that’s exactly right, because I had spent—you know, in a very difficult relationship for 24 years where I was the good girl. I had still played the role that I did as a kid. I never said anything. I didn’t speak up for myself. So all of a sudden, I’m like, “[bleep] you!” You know, I’m like, “Shut the [bleep] up!” or whatever I’m saying.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m glad that we’re not doing this live, because now we can—

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Sorry.

AMY GOODMAN: Those beeps you hear, folks, you’re not meant to hear what was originally said.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Anyway, so it’s just—it’s so great, because it’s the first time in my life that I can actually fight with somebody that I love deeply and know that I’m safe and I’m OK, and he’s not going to leave, and I’m not going to—you know, I’m not—it’s just not a dangerous place for me. Saying how you felt, when I was a kid, was dangerous. And I didn’t know that in my relationship with my ex-husband, at the same time, I didn’t know that I could be safe there, either, not that he was dangerous, but I didn’t know. I wasn’t that advanced in my own understanding of myself to understand that I could have been OK or—and I’m not a martyr anymore. I don’t—you know, I don’t play the victim.

BARBARA KOPPLE: And then, also, too, after the fight, they proceed to rock climb. And you need so much trust in that, because, you know, you’re tethered to each other. And it just showed that they got over that, that was finished, and there they are with another challenge. And there’s Mariel going up there with her bare hands up the rock and doing it.

AMY GOODMAN: You also talk about assumptions. This is Mariel Hemingway driving and talking about whoever you may think you know about their life, when you don’t really know.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: There’s no one outside of yourself that can help you or love you the way you need, except you. You know, this is what I talk about to people. I know a lot about how people can live a better life, how they can be happy, how they can not fear stuff that I’ve feared my whole life. But sometimes it’s such a misunderstanding of the being I really am, you know, and I get that. I often say it. I’ll speak to groups of people. “Yeah, I know you think you know me. You know, yeah, tall blonde, no problems. Well, what does she have to say to me?” I say that. Of course. I get it. I would think the same thing. Guess what. Bunch of funky [expletive] in my family; you know, I’m scared, too.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Mariel, talking about your life, saying people are going to assume all sorts of things about you because you’re this famous starlet actress.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, look at what you have been suffering.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: And that’s the—and I think that’s with so many people. It’s not just my story. I think many people put on masks, and we play games, and we think that—and we try to act a certain way, because—because it’s survival, because it’s running from crazy. It’s whatever it is. It’s how you were brought up. It’s that you don’t want to get in trouble. I’m a—you know, there—I think we reenact our patterns until we can see those patterns. And that’s what I did. And, you know, and I get it. And it’s like I said in the thing, “Oh, I get it. You know, that’s—I’d think the same thing.” But then, when you, you know, crack open that—or you, you know, peel a layer of that onion, you can see more and more and more. As you just peel away at those layers, you see that a person is—has many more layers to them.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, you, yourself, said that you have felt suicidal thoughts in the past, and you have this unbelievable history. How many people in your family have committed suicide?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Well, seven suicides that we know, and we think they’re—

AMY GOODMAN: And who were they?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Well, they’re my—my great-grandfather, Ernest’s father; Ernest; my grandmother’s father; my great-uncle; my uncle; a cousin; and Margaux. And then there might be one more.

AMY GOODMAN: And Margaux drank herself to death.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: She didn’t drink herself to death, no. She took—she took—

BARBARA KOPPLE: Phenobarbital.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: —phenobarbital.

AMY GOODMAN: And overdosed.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: And overdosed, yeah. And initially, it was thought—well, the family—they said it wasn’t suicide, and the family was like, “OK, it’s not suicide.” And they never admitted it. And I never admitted it. And we were all like, “No, no, no, no.”

It was surreal. I actually didn’t think it was her. I thought it must be my oldest sister, who had been suffering from mental illness for the longest time. I mean, I knew Margaux suffered from addictions, but I didn’t realize that the depth of mental illness was so deep, although I did have some signs, because there were some things that she was, you know, doing some kind of psychotic—there was some psychotic behavior that my dad was like worried about. But we all said, “Oh, it must be something else.” Or—

AMY GOODMAN: So, how would you do things differently now—you say you’ve learned so much, and even about your sister’s illness—if you knew then what you know now about how to deal with someone who’s mentally ill or suicidal?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: You know, like what we want this film to do, talk, speak about it, be in their lives more, have more compassion. And also, there’s a lot of modalities, like I really know how lifestyle can change the way your brain is balanced. So I would have—if she would have been willing, I would have taken her life and said, “Look, give me—give me a year to shift the way that you eat, shift the way that you think, and teach you about different things.” But it also wasn’t our dynamic, because there’s a lot of like, “I’m the big sister, you’re the little sister.” So there was that, you know. But if—in a different world where I could make it all up, I would have helped in that way.

AMY GOODMAN: So this film, Running from Crazy, has just premiered at Sundance, and it’s getting a lot of attention. A lot of people saw it here, but many, many more people will see it around the country. What do you hope to do with it, for both of you? Barbara Kopple?

BARBARA KOPPLE: Well, for distribution, we’d like to see it show theatrically. And we’d also like to have community groups and mental illness groups and people just get behind it and use it in a pivotal way, so that people are able to really, say, talk to each other. Don’t be afraid. Don’t keep this under the shadows. This is something we have to deal with.

AMY GOODMAN: So where are you headed, and with this film?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: I feel absolutely liberated in my life. You know, 51 and here I am, I’m being reborn. But I feel like I’m younger and happier and more aware than I’ve ever been. And so, for me, the film is a—is a tool. It’s a learning tool. It’s a—it’s like Barbara said: It’s a film about hope. I would love to see it be in rehab centers. In fact, somebody wrote me and said, “We thought about this film. We saw it, and we thought about it all night, and then we all decided that it should be in universities and in rehab centers to help people.” And to be able to go speak around the country and talk about—talk about my own story, just so that it can help other people to talk about their own story, just so they don’t feel alone, so they feel supported.

AMY GOODMAN: Just being here, your film just opening—you were at the opening. Did people come up to you afterwards?

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Oh, my god. Well, that’s the beautiful thing. I mean, because it was scary to see it here and see it with people. But the wonderful thing is, everybody comes up, and it’s not—they have tears in their eyes, not because of me, but because they say, “Oh, my god! That’s my story! You know, you have the same” — and I know that. See, that’s the only thing that I came into this knowing. I knew that I wasn’t alone in this story. Everybody has some similar version of some dysfunction or pain of some kind, or has been touched by mental illness or even cancer, whatever it is. But for somebody to be able to go, “Oh, it’s OK to talk about,” and actually it shifts the paradigm. It breaks a cycle. I would like to help people break that cycle. But I also am doing the WillingWay and going out there and just—like, I love that. I love helping, inspiring people to find their health and wellness. And I’d like to act again, too, just on a side note.

BARBARA KOPPLE: And also, too, after the screenings, it was very—people confessed.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Yeah.

BARBARA KOPPLE: I mean, we had a moderator, who whispered to me, “I fought so hard not to have to be the moderator for this film.” And I said, “Why?” And he said, “I had someone very close to me commit suicide.” And I said, “Do you want to talk about it?” And he talked about it in front of 600 people at the premiere screening.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: It was so powerful.

BARBARA KOPPLE: He said, “I had a sister who five years ago committed suicide. I haven’t talked about it.” And his voice started to quiver. And then other people would come up to us after and say, “I lost my son a month ago,” or people would tell us different stories and just hold onto us and cry.

AMY GOODMAN: Barbara Kopple, director of Running from Crazy, and actress Mariel Hemingway. The film focuses on Mariel Hemingway’s family history of mental illness and the suicides of seven relatives, including her sister, supermodel Margaux, and her grandfather, the great writer Ernest Hemingway.

Media Options