Related

Topics

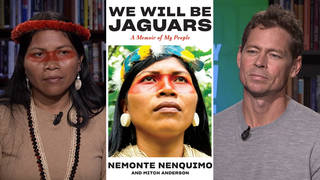

Guests

- Monserrat Martinezworks in the investigation unit of Pro-Búsqueda Association for Missing Children, which was attacked on November 14.

- Alexis Stoumbelisexecutive director of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES).

On Thursday, armed men sabotaged an El Salvadoran nonprofit dedicated to finding children who went missing three decades ago during a time when the United States was backing Salvador’s military government. The intruders broke into the Pro-Búsqueda Association for Missing Children, destroyed four of its offices, and set fire to its archives. They also stole computers, possibly containing sensitive information about children stolen by members of the military between 1980 and 1992. El Salvador’s human rights ombudsman, David Morales, told the Associated Press the attack could be related to an appeal before the country’s Supreme Court that would eliminate amnesty for people who carried out war crimes. We go to San Salvador, El Salvador, to speak with Monserrat Martínez, who works in the investigation unit of the Pro-Búsqueda Association for Missing Children. We are also joined by Alexis Stoumbelis, the executive director of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Armed men have sabotaged a Salvadoran nonprofit agency dedicated to finding children who went missing during three decades ago during a time when the United States was backing Salvador’s military government. On Thursday, the intruders broke into the Pro-Búsqueda Association for Missing Children, destroyed four of its offices, and set fire to its archives. They also stole computers, possibly containing sensitive information such as cases of children stolen by members the military between 1980 and 1992. Efforts to investigate those cases have been obstructed by the military’s refusal to share DNA records.

Shortly after the attack, El Salvador’s human rights ombudsman, David Morales, visited the organization and commented on what had happened.

DAVID MORALES: [translated] On a group that struggles for the community and tries to help victims of armed conflict, we haven’t seen this type of attack for a long time. Traditionally, the political purpose is to intimidate, pursue and destroy information that shows what happened in the past.

AMY GOODMAN: Morales told the Associated Press the attack could be related to an appeal before the country’s Supreme Court that would eliminate amnesty for people who carried out war crimes, and he requested the attorney general to prioritize investigating the attack.

For more, we’re going to San Salvador, El Salvador, where we’re joined via Democracy Now! video stream by Monserrat Martínez, who works in the investigative unit of the organization that was just raided and with its files destroyed on Thursday. In Washington, we’re joined by Alexis Stoumbelis, the executive director of CISPES, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Monserrat, describe what happened in your offices in San Salvador and why this is so critical at this moment, as your organization comes—that started with Archbishop Romero; he was gunned down by U.S.-backed military, paramilitary forces in 1980—why these files were so important that have been destroyed.

MONSERRAT MARTÍNEZ: Good morning. Well, the files that were taken from our office contained legal information and testimonies of cases of forced disappearance of children during the armed conflict, and, for us, have the proof to put these cases into the national system of justice in El Salvador. So, we are still evaluating the damages and the kind of information they took, but we are afraid that this information can be helpful for us, for our legal department, to put these cases into the legal system.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what has happened in recent months in terms of being able to come to terms with what happened back then that might have prompted people to do this attack?

MONSERRAT MARTÍNEZ: Well, in the last months, there has been some events in El Salvador that are a coincidence in the time. And we now—we need to know the relation between these events. But, for example, we had the problem with the Tutela Legal. It’s an organization created by the archbishop, Monsignor Romero, where they contain a lot of files also on testimonies of human rights violation during the armed conflict. And the actual archbishop of San Salvador decided to shut down that organization and is not allow to anybody to obtain that information or those files. That’s one of the events. The other one is what will happen with the amnesty law. There is an initiative to put down this law, and now we are respecting the decision of the court. Yesterday we have this violent attack against Pro-Búsqueda, so while we can think that there is a relation between these events, although in our case we need to evaluate first our damages and the kind of information that these three men took with them.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to bring Alexis Stoumbelis into this conversation, executive director of CISPES. She’s in Washington. Explain the significance of this in terms of trying to find justice in El Salvador for the thousands of people who were killed during the 1980s.

ALEXIS STOUMBELIS: Yeah, I mean, one thing that’s really important to understand about the amnesty law is, you know, it was put in place in 1993 by the right-wing ARENA government. The ARENA party, of course, was founded by the father of the Salvadoran death squads, Roberto D’Aubuisson. And so, since putting in—the law was put in at the end of the war in 1993, just before the U.N. Truth Commission would issue its report naming that the Salvadoran state or state forces were responsible for over 85 percent of the 75,000 civilian deaths that occurred during the civil war. And so, it’s really important to understand that since that time, literally no one has been brought to justice or brought to criminal charges in El Salvador for any of the human rights atrocities that happened, even, you know, incredibly huge events like the El Mozote massacre in 1981. So it’s been this ongoing struggle.

AMY GOODMAN: Where 800 people were killed.

ALEXIS STOUMBELIS: Yes. And, you know, the Inter-American Human Rights Court in Costa Rica last year charged the Salvadoran state with responsibility for those crimes and actually ordered the state not to allow the amnesty law to be an obstacle to that. And so, it certainly really looks like the, you know, abrupt closure of Tutela Legal, which holds 50,000 records, including 80 percent of the cases that were used in the U.N. Truth Commission—that being cut off in terms of access—no one can get in to see if archives are even safe at this point in time—and now the attack on Pro-Búsqueda, it certainly looks like the right-wing oligarchy, who are the ones who stand to gain—stand to lose, of course, the most if the amnesty law is ever overturned, are, you know, reaching increasingly violent and desperate measures to make sure that those—that evidence never comes to light.

AMY GOODMAN: Alexis Stoumbelis, we want to thank you for being with us—that wraps up our show—executive director of CISPES, and Monserrat Martínez, joining us from San Salvador, from the organization that was attacked and their files destroyed. We’ll continue to follow this story.

Media Options