Related

Guests

- Randall Robinsonfounder and past president of TransAfrica. He helped found the Free South Africa Movement and was arrested many times during the 1980s protesting the apartheid regime. He is now a law professor at Pennsylvania State University and author of several books.

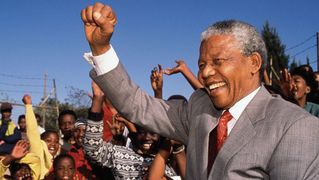

In 1964, Nelson Mandela was sentenced to life in prison on Robben Island. He would become the most famous political prisoner in the world and his freedom became a central demand of the international anti-apartheid movement. Despite growing international pressure in the 1980s, the apartheid government received strong backing from the Reagan administration and Margaret Thatcher in Britain. The African National Congress was considered a terrorist organization by both nations. Mandela was listed on the U.S. terrorist watch list until 2008. We speak to Randall Robinson, founder and past president of TransAfrica. He helped found the Free South Africa Movement and was arrested many times during the 1980s protesting the apartheid regime.

Click here to watch our special coverage of the life and legacy of Nelson Mandela.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: People singing outside Nelson Mandela’s home in Soweto, the epicenter of South Africa’s decades-long struggle against apartheid. You can go to our website at democracynow.org to see highlights of our coverage of Nelson Mandela over the years, including clips of former Archbishop Desmond Tutu from the film Viva Madiba: A Hero for All Seasons by Danny Schechter; as well as my interview with poet and activist Dennis Brutus, who was imprisoned with Mandela on Robben Island; and our trip to Soweto, to the home of Nelson Mandela, when we covered the U.N. climate summit in Durban, South Africa. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: As we continue our coverage of the death of Nelson Mandela, we begin with Randall Robinson, founder and past president of TransAfrica. He helped found the Free South Africa Movement and was arrested many times during the 1980s protesting the apartheid regime. He is now a law professor at Pennsylvania State University. He joins us from his home in Saint Kitts.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Randall.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Thank you.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Your immediate reactions to the news that you heard yesterday of—that the world heard, that Nelson Mandela had passed?

RANDALL ROBINSON: Well, deeply, deeply moved. He was an extraordinary human being. Seldom do you find combined in one personality this kind of brilliant thoughtfulness. He was a contemplative man. He was nuanced. He was not a doctrinaire. He was charming, and he was warm. At the same time, he was as strong as steel and highly principled, and a figure around which, of course, so many across the world could easily rally. He was, of course, everything to the anti-apartheid movement, and seldom do you find that. His life was a very rare, a very rare thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Randall Robinson, you were pivotal in this country leading the anti-apartheid movement, being arrested numerous times. Talk about that struggle. I mean, we just talked about how, in fact, President Nelson Mandela was not taken off the terrorist watch list in the United States until 2008. That was 14 years after he was elected president. Each time he came into the United States—I suppose that included 1990 right after he was released from prison—he got a waiver to come in, as even his foreign minister did and other leaders of the ANC.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Well, when he—when we went to the embassy on November 21st, 1984, to meet with Ambassador Fourie, Nelson Mandela was not a popular figure in policy circles in the United States. I remember giving a speech in San Francisco to American mine interest people, mining interest people. And when I suggested that he would one day be president of South Africa, I was roundly booed, just in a very hateful kind of way. And this was a general feeling in American policy circles about Nelson Mandela. We went to the embassy and met with Ambassador Bernard Fourie and told him that we weren’t leaving the embassy until Mandela had been released, along with Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki and all of the other political prisoners. And, of course, President Reagan had of course rolled out the carpet to the white government, and in addition to which the State Department had promised South African officials that the United States would remove their polecat status and legitimize them in the eyes of the world.

And so, things were quite different then. But we knew what kind of man Nelson Mandela was, and we knew what he was fighting against. And the ambassador made a bad strategic error when he chose to have us arrested that day, when I went with Congressman Walter Fauntroy and Mary Frances Berry. And the three of us were arrested, followed by 5,000 Americans who came to the embassy over the following years—year to be arrested. And of course that helped to propel through the Congress the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986. So, it—and then American investments in South Africa began to tumble. And, of course, that, combined with the internal pressures in the country, produced the circumstances in the government there, the readiness to negotiate and to ultimately release Nelson Mandela.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, and the critical importance of that divestment movement? Because now we’re hearing all of the accolades and the lionizing of Mandela, but really, our government really played a key role in prolonging the apartheid system and resisting the efforts by young people across the country and in colleges and universities building a movement for divestment from South Africa. How critical do you think that was in finally convincing the apartheid government that they would have to negotiate a transition to democracy?

RANDALL ROBINSON: It made every difference. There was no inclination in government to change policy. There was in place a policy that the Republican government called “constructive engagement,” meaning that, in effect, that we were on South Africa’s side and that sanctions would be the wrong thing, even though the ANC was asking us to do all that we could to put in place sanctions, because they knew, and we knew, that unless the government of South Africa felt the steel of some penalty for what they were doing, nothing would ever change. But once the loans began to disappear and the corporate investors began to disappear and the income and the size of the South African economy began to shrink, because of these efforts and because of these civil disobedience efforts across the United States, it made all the difference in the world.

And so, then we saw passed in 1986 in October the Comprehensive Act, with a Republican Senate overriding the veto of Ronald Reagan. It was the only time in the 20th century that an American president had suffered an override for a foreign policy measure, an override of a veto. So, it was historic. And it happened because of the leadership in the Congress working with us, the leadership of Senator Ted Kennedy, the leadership of Bill Gray in the House, the Congressional Black Caucus and many others—Richard Lugar, a Republican leader. Lowell Weicker, a Republican from Connecticut, became the first American member of the United States Senate to be arrested in an act of civil disobedience. Sentor Weicker called me and said—I didn’t know his at the time. He called me and said, “I want to be arrested.” And he came and did that. And so, the movement was broad and deep and national, and it made a significant difference. And it turned our country around and, for once, put us on the right side of an issue.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Randall Robinson. He’s in Saint Kitts in the Caribbean. Sorry for the poor phone line. But, Randall, we wanted to get you to respond to President Mandela speaking at Riverside Church. This was September 1998, a year before President Mandela retired from office. He visited the United States—actually, this was the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York, paying tribute to Americans who supported the anti-apartheid movement.

PRESIDENT NELSON MANDELA: Ladies and gentlemen, it was important that during what is probably our last official visit to your country before retiring from office next year, we should spend time with those Americans who have been so closely linked with the struggle for freedom in South Africa. Our victory in defeating apartheid was your victory, too. To you and to all of the American people who supported the anti-apartheid struggle, we thank you from the bottom of our hearts for your solidarity.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Randall Robinson, I wanted to ask you, especially—he was speaking there just before retiring from office, and there’s been a lot of talk in the media about—about his legacy in terms of first willing to forgive his oppressors. But I’ve always been most impressed by his willingness to step down. So many revolutionary leaders come to power and then decide that they are indispensable to their society, then they stay in office term after term. But Mandela’s willingness to step down after one term really sent a powerful message in terms of democratic transformation. I’m wondering your thoughts about that.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Well, he was one of the most secure men that I ever had the privilege to know. And I think he was very much outcome-oriented. And he thought through everything with that kind of quantitative analysis. What would the outcome be? And what do we do to try to accomplish that outcome? And at the same time, he was an incredibly thoughtful man. I was in a meeting with him around 7:00 in the morning at—in Johannesburg. I had taken a delegation of black American leaders there before—just before he became president. We were sitting in this function room on the first floor of the hotel, just the two of us, at 7:00 in the morning to plan the day. And a hotel maid walked into the room. And he stood up. And she was stunned, and she said, “Oh, Madiba, I didn’t know you were in here.” And he was very cordial to her, and he smiled. And he had this gift of making people comfortable. So, he would sacrifice what some would think were their own sort of needs of personality. He didn’t have those kinds of needs, as far as I could see. He was a whole person, as strong and balanced and as principled as you will ever find a human being.

AMY GOODMAN: Randall Robinson, we want to thank you for being with us, founder and past president of TransAfrica. He helped found the Free South African Movement, arrested numerous times during the 1980s protesting the apartheid regime, now a law professor at Pennsylvania State University, speaking to us from the Caribbean, from his home in Saint Kitts.

Media Options