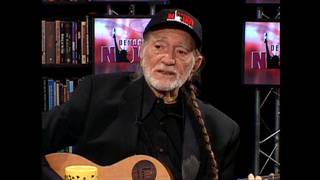

Country music legend Willie Nelson turns 80 years old today. Last night he performed a benefit birthday concert in Austin to raise money for the fire department of West, Texas — the town devastated by a fertilizer plant explosion that killed 14 people earlier this month. Nelson was born just a few miles away in Abbott, Texas, in 1933. In addition to being one of the most celebrated country musicians, Nelson has been politically active for decades. He co-founded Farm Aid, the annual benefit and awareness-raising concert for small farmers. Nelson has partnered in a biodiesel plant that fuels trucks with vegetable oil. And he serves on the advisory board member for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. We broadcast an excerpt of our hour-long interview with Nelson when he joined us in our studio in 2008.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Willie Nelson singing “A Peaceful Solution” in our old studios at DCTV. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We end today with country music legend Willie Nelson, who turns 80 years old today. Last night, he performed a benefit birthday concert in Austin to raise money for the fire department of West, Texas, the town devastated by the fertilizer plant explosion that killed at least 14 people earlier this month. Willie Nelson was born just a few miles away in Abbott, Texas, on this day, April 29th, 1933.

In addition to being one of the most celebrated country musicians, Willie Nelson has been politically active for decades, co-founded Farm Aid, the annual benefit and awareness-raising concert for small farmers; also serves on the advisory board for NORMAL, the National Organization for Reform of Marijuana Laws.

We end today’s show with our interview that we did in 2008 along with co-host Juan González. I began by asking Willie to talk about his upbringing in Texas.

WILLIE NELSON: I was born in Abbott, Texas, a little small town in central Texas, and I was raised by my grandparents. And my parents divorced when I was six months old, and my grandparents raised me. And my granddad was a blacksmith, and so I spent a lot of time in the blacksmith shop, growing up there. And both my grandmother and my granddad were music teachers and singers, and they sang the old-fashioned shape notes, you know, and we’d sing in church: do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do. I had a lot of fun and learned a lot. And I feel like that the education that I received in Abbott, Texas, was as good and as general as one that I could have found anywhere in the world. Everything that I found in the rest of the world, I found in small amounts in Abbott, Texas, so it was really a good training ground.

AMY GOODMAN: You were born what year?

WILLIE NELSON: 1933.

AMY GOODMAN: What’s your birthday?

WILLIE NELSON: April 29.

AMY GOODMAN: April 29th, 1933.

WILLIE NELSON: 1933.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wanted to ask about the time in Texas. Obviously, Texas has always had a large Mexican population and influence, and Tex-Mex music developed in southern parts of the state. Most people are not aware that there’s been quite a bit of intermingling or ties between Tex-Mex and country, in general. Any influence at all during your youth?

WILLIE NELSON: Yeah. Oh, a lot. In fact, I grew up across the street from, you know, the Villarias, which was a great Mexican family there. In fact, there was three houses right across the street from me. So, day and night, I listened to Mexican music, and I’m sure, you know, my guitar playing, singing, writing, whatever, has a lot of Mexican flavor there, but it comes natural.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the whole subgenre outlaw country? What does that mean? How did you get into it?

WILLIE NELSON: Well, Waylon, I think, was—had a lot to do with the “outlaw” title, and maybe, me, too, but we were sort of unconventional, I guess, when we went to Nashville, and we had our own ideas of what we wanted to do and the way we wanted our music to sound. I mean, Waylon and I didn’t even know each other at the time, but we both had the same rebellious ideas, that we were stubborn and wanted to play our music the way we wrote it and the way we feel it. And there was elements in Nashville—and not only Nashville, around the world—where whoever put up the money said this is the kind of music we want. So there was always that problem, and there still is. But Waylon and I managed to get it done our own way, and, you know, they put the label “outlaw” on us for doing it. And I wear it as a badge, and I kind of enjoy it.

AMY GOODMAN: Johnny Cash—talk about your relationship with Johnny, his influence and what he meant to you and what he means to music.

WILLIE NELSON: Well, of course, John was one of the original instigators, one of the original outlaws, and he had always done it his way, and he’d always gone against the grain, uphill, whatever. And so, eventually, it was inevitable that we had to get together. So—

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you meet?

WILLIE NELSON: I met him—well, he and Waylon lived together in Nashville for awhile, and Kris was in town, and I was there, so—in Nashville.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson.

WILLIE NELSON: Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson and Johnny Cash. And eventually we did the Highwaymen recordings and tours, which was a traveling circus. It was 278 pieces of luggage, because all our families and kids and everybody traveled with us around the world. And we did two world tours that way and really had a lot of fun.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the music industry and talk about the kind of music that, you know, corporate publishing allows and how you have led your life?

WILLIE NELSON: Well, there’s always the music industry. There’s always the business part of it. And I’ve always tried to dodge that part of it, because I didn’t really want to go along with all those things, where it has to be done this way, a song has to be two minutes long or has to have this and that in it. So the music industry or the music business and I never did really gel all that well.

AMY GOODMAN: You were with RCA Victor Records?

WILLIE NELSON: I was with RCA. Before that, I was with Monument Records, and before that I was with an independent label. And so, through the years, I’ve been with a few labels. But, yeah, I was with RCA when Chet Atkins was running RCA, the Nashville division.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We often, on the show, try to deal with what’s happening to media companies around the world, especially in the United States, and we’ve done a lot of emphasis on Clear Channel and the impact of Clear Channel and the ownership of radio stations on the kind of music that they play. From your perspective as a musician, what’s been the impact of all this consolidation of ownership of all these radio stations?

WILLIE NELSON: When I was a young guy growing up and playing around and playing Dallas, Fort Worth, Waco, whatever, and taking my band, one of the good things back in those days was that I could call a disc jockey there in Fort Worth and say, “Hey, I’ve got a new record. I want to bring it over. And play it for me, because I’m playing Panther Hall this next week, and I need the promotion.” And you could do that. Or else I could write a song today and record it tonight, and within two weeks I could have it out on the market, because it was set up that way.

Now, that’s almost impossible. You write a song today, you record it next year, and then, two years later, it comes out. And we’ve lost really control over our music, because of the fact that so much of it is done now—it’s programmed in another state, somewhere else. And so, when I was a disc jockey, I used to go in and grab a handful of records and go in there and sit down and play for two or three hours.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Where were you a disc jockey?

WILLIE NELSON: I started out in Texas at KHBR in Hillsboro, then KBOP in Pleasanton and KCNC in Fort Worth. And then I went around to—went up to Vancouver, Washington, KVAN up there. So, all over the country I was a disc jockey, and it sort of fit in with what I was playing music in the clubs at night, so I could enhance my income a little bit by disc jockeying.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you play a song from your Highwaymen days with Kris and Waylon and Johnny Cash?

WILLIE NELSON: Well, let me see. What would we do? Well, we did “Mama Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys.” We did that. I can do a verse of that for you.

Mama, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys.

Don’t let ’em pick guitars and drive them old trucks.

Let ’em be doctors and lawyers and such.

Mama, don’t let your babies grow up to be cowboys.

They’ll never stay home, and they’re always alone,

even with someone they love.

Cowboys ain’t easy to love, and they’re harder to hold.

They’d rather give you a song than diamonds and gold.

Lone Star belt buckles and old faded Levi’s and each night begins a new day

And if you don’t understand him and he don’t die young,

he’ll probably just ride it away.

AMY GOODMAN: And for the people you sing for, which is people in this country and all over the world—you’re one of the most famous musicians in the world today—your sense of their feeling about our country, about your country, about the United States of America?

WILLIE NELSON: Well, I’ve traveled around over the years; over the last several years, I’ve traveled around a lot, and I got a lot of different feedback from people around. And we’re not as loved as we think we are around the world. That’s for sure. I think most people realize that our problems are our government, not me and you individually, except that we can—must have some sort of responsibility, because they’re in there and they were elected, so we have to defend ourselves on those lines. But a lot of people realize that, you know, now that they’re in there, what are you going to do about it? So I say get them out.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Your message, if you had to give to young people today, from the experience that you’ve had as a musician and as a social activist in terms of what the potential that they have to do something about where our country is headed?

WILLIE NELSON: Well, somebody one time said you can—you know, one person can’t change the world, but one person carrying a message can change the world. And that’s what I think is going on now. I think a lot of young people are realizing that their voice is ready to be heard. They are really important, and they feel that importance, and they know that they have to do something. You know, when you see something wrong, you sit around, and you can say, “Well, I’m either going to do something,” or “I’m going to do nothing.” You have to make the decision. A lot of the kids out there are saying, “Wait a minute, we can do something.”

AMY GOODMAN: Music legend Willie Nelson turns 80 today. A lot of websites say it’s the 30th, tomorrow, but we talked to his wife Annie; she said he was born just before midnight, the doctor recorded it after midnight, so legally it’s the 30th, but really it’s the 29th.

Media Options