Guests

- Julian Assangefounder and editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks. He was granted political asylum by Ecuador last year and sought refuge almost a year ago at the Ecuadorean embassy in London because the British government promises to arrest him if he steps foot on British soil. Assange is the co-author of book, Cypherpunks: Freedom and the Future of the Internet.

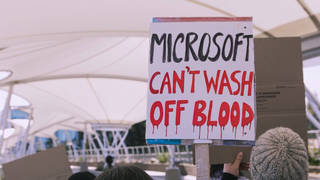

The sentencing hearing for Army whistleblower Bradley Manning begins today following his acquittal on the most serious charge he faced, aiding the enemy, but conviction on 20 other counts. On Tuesday, Manning was found guilty of violating the Espionage Act and other charges for leaking hundreds of thousands of government documents to WikiLeaks. In beating the “aiding the enemy” charge, Manning avoids an automatic life sentence, but he still faces a maximum of 136 years in prison on the remaining counts. In his first U.S. television interview since the verdict, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange discusses the Manning “show trial,” the plight of National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden, and the verdict’s impact on WikiLeaks. “Bradley Manning is now a martyr,” Assange says. “He didn’t choose to be a martyr. I don’t think it’s a proper way for activists to behave to choose to be martyrs, but these young men — allegedly in the case of Bradley Manning and clearly in the case of Edward Snowden — have risked their freedom, risked their lives, for all of us. That makes them heroes.” According to numerous press reports, the conviction of Manning makes it increasingly likely that the U.S. will prosecute Assange as a co-conspirator. During the trial, military prosecutors portrayed Assange as an “information anarchist” who encouraged Manning to leak hundreds of thousands of classified military and diplomatic documents.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: The sentencing hearing for jailed Army Private Bradley Manning begins today, one day after he was convicted of six counts of violating the Espionage Act and over a dozen other charges for giving WikiLeaks hundreds of thousands of U.S. diplomatic cables, raw intelligence reports and videos from the Iraqi and Afghan battlefields and elsewhere. Military judge Colonel Denise Lind found Manning not guilty on the most serious charge of aiding the enemy, which carried a potential life sentence without parole. Reporters who were in the courtroom say Manning showed no emotion as he stood to hear Judge Lind read the verdict. The sentencing phase of his trial is expected to last at least a week with more than 20 witnesses set to appear. The 25-year-old Manning faces a maximum of 136 years in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: In a statement to The Guardian, Manning’s family expressed thanks to his civilian lawyer, David Coombs, who worked on the case, which has now lasted three years. An unnamed aunt of Manning said, quote, “While we’re obviously disappointed in today’s verdicts, we’re happy that Judge Lind agreed with us that Brad never intended to help America’s enemies in any way. Brad loves his country and was proud to wear its uniform,” she wrote.

Ben Wizner, director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy & Technology Project, responded to the verdict Tuesday saying, quote, “It seems clear that the government was seeking to intimidate anyone who might consider revealing valuable information in the future.”

Meanwhile, House Intelligence Committee Chair Mike Rogers and Democratic Ranking Member Dutch Ruppersberger issued a joint statement that, quote, “justice has been served,” adding, “There is still much work to be done to reduce the ability of criminals like Bradley Manning and Edward Snowden to harm our national security.”

Well, today we spend the hour on the Manning verdict and its implications. We begin with Julian Assange, founder and editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks, which published the secret cables obtained by Bradley Manning. According to numerous press reports, the conviction of Manning makes it increasingly likely that the United States will prosecute Assange as a co-conspirator. During the trial, military prosecutors portrayed Assange as an information anarchist who encouraged Manning to leak hundreds of thousands of classified military and diplomatic documents.

Julian Assange joins us via Democracy Now! video stream from the Ecuadorean embassy in London. He took refugee in the embassy in June of 2012 to avoid extradition to Sweden, where he’s wanted for questioning around sex assault allegations but has never been charged. He remains in the embassy there because the British government promises to arrest him if he steps foot on British soil. This is his first interview with a U.S. TV show since the Manning verdict.

We welcome you back to Democracy Now!, Julian Assange. What is your response to the verdict?

JULIAN ASSANGE: Thank you, Amy. First of all, I must correct you. I have been given political asylum in this embassy in relationship to the case that is in progress in the United States. It’s a common media myth that’s put about that my asylum here is in relation to Sweden. It is not. Here I am.

My reaction to the verdict yesterday, well, first of all, really one of surprise in relation to the timing. This is a case that has been going for three years, two months at trial, over 18 months of interlocutory motions, at least 40,000 pages of judgments and evidence that the judge was required to read. But she has made her decision on 21 separate counts over the weekend. We said at the very beginning of this process that this was a show trial. This is not a trial where any justice can come about, because the framing of what was possible to debate was set from the very beginning. It was not possible for Bradley Manning’s team to say that he was well-intentioned. Motive was taken out of the case. The prosecution has not alleged that a single person came to harm as a result of Bradley Manning’s alleged actions, not a single person. And, in fact, no evidence was presented that anyone was indeed harmed. The defense is not allowed to argue that that means that these charges should be thrown out.

And so what we are left with here is 20 convictions for Bradley Manning. Five of those are for espionage. This is a case where everyone agrees that Bradley Manning provided the media information about war crimes and politics, some of which was published by the media. There is no allegation that he worked with a foreign power, that he accepted any personal benefit for the disclosures that he engaged in. And yet, we see him being convicted for five charges of espionage. It is completely absurd. It cannot possibly be the case that a journalistic source, who is not communicating with a foreign power, who is simply working for the American public, can be convicted of five counts of espionage. That is a abuse, not merely of Bradley Manning’s human rights, but it is an abuse of language, it’s abuse of the U.S. Constitution, which says very clearly the Congress will make no law abridging the freedom of the press or of the right to speech. That’s clearly been subjugated here.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Julian Assange, you said yesterday that the aiding the enemy charge for which Bradley Manning was acquitted was absurd, and it was put forward, quote, “as a red herring,” you said. Could you explain what you mean by that?

JULIAN ASSANGE: Well, you will have seen the way WikiLeaks has made its statements today. We have Bradley Manning, right now, despite having been acquitted of effectively being a traitor, aiding the enemy—he was acquitted of that—but he faces 136 years in prison, which is more than a life sentence. So, this aiding the enemy charge, while it has attracted a lot of people’s attention, because it has a possible life sentence or death penalty, really, it was just part of the extent of overcharging in this case. You know, at the very minimum, perhaps Bradley Manning could have been charged, say, with mishandling classified information. Of course, I think he should be acquitted of such a charge, because under the First Amendment and a number of other obligations we all have, he should be free to break one obligation to fulfill another: the higher obligations of exposing crimes and satisfying the Constitution. But where we have a aiding the enemy charge soaking up our public attention and many people going, “Oh, well, look, the justice system is just, because it’s taken this one out,” actually, this is one charge out of 21 different offenses. He’s still up for 136 years. The substantive aspect that a alleged journalistic source, pure in their motives, as far as there are any allegations for, and who received no financial payment, has been now convicted of five counts of espionage, that is absurd.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to break, but we’re going to come back to this discussion. We’re speaking to Julian Assange, our exclusive interview with him inside the Ecuadorean embassy. He’s been granted political asylum by the country of Ecuador but can’t leave the embassy for fear of the British government arresting him. Julian Assange is the founder and editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks. We’ll continue with him in a moment.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. This is the broadcast on the day after the Bradley Manning verdict was announced, that he was acquitted of aiding the enemy but found guilty on a number of espionage-related and other charges. He faces 136 years in prison. The sentencing phase of the trial begins today 9:30 Eastern time at Fort Meade, where the court-martial has taken place. Just after the Bradley Manning verdict was announced Tuesday, Associated Press reporter Matt Lee asked State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki to comment on the verdict. Let’s go to a clip of their exchange.

MATTHEW LEE: What is the State Department’s reaction to the verdict in the Manning trial?

JEN PSAKI: Well, Matt, we have seen the verdict, which I know just came out right before I stepped out here. I would—beyond that, I would refer you to the Department of Defense.

MATTHEW LEE: Well, for the—

JEN PSAKI: No further comment from here.

MATTHEW LEE: For the entire trial, this building had said that it wouldn’t comment because it was pending, it was a pending case. And now that it’s over, you say you’re still not going to comment?

JEN PSAKI: That’s correct. I would refer you to the Department of Defense.

MATTHEW LEE: Can I—OK, can I just ask why?

JEN PSAKI: Because the Department of Defense has been the point agency through this process.

MATTHEW LEE: Well, these were State Department cables, exactly. They were your property.

UNIDENTIFIED: State Department employees were [inaudible].

JEN PSAKI: We don’t—we just don’t have any further comment. I know the verdict just came out. I don’t have anything more for you at the time.

MATTHEW LEE: Well, does that mean—are you working on a comment?

JEN PSAKI: I don’t—

MATTHEW LEE: Are you gratified that this theft of your material was—

JEN PSAKI: I don’t expect so, Matt, but if we have anything more to say, I promise everybody in this room and then some will have it.

MATTHEW LEE: OK. I’m a little bit surprised that you don’t have any comment, considering the amount of energy and time this building expended on assisting the prosecution.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Associated Press reporter Matt Lee questioning State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki right after the verdict came down. Our interview continues with Julian Assange, founder and editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks. Your response to the government’s, U.S. government’s, lack of response and what this means also, Julian, in your own case?

JULIAN ASSANGE: It’s quite interesting to see the State Department doing that. The State Department has made many comments about this affair over the past three years, saying—Secretary Clinton, for example, saying that this was—once again, an absurd piece of rhetoric—an attack on the entire international community by our publishing organization and, I assume, by proxy, by our source, she would say.

Well, look, this investigation against our organization is the largest investigation and prosecution against a publisher in United States history and, arguably, anywhere in—anywhere in the world. It involves over a dozen different government departments. The tender for the DOJ to manage the documents related to the prosecution—the broader prosecution against WikiLeaks and myself, and not just the Manning case—is $1 [million] to $2 million per year just to maintain the computer system that manages the prosecution’s documents. So I assume those sort of statements by the State Department are a mechanism to reduce the perception of their involvement, which has been extensive over the last three years.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I want to turn to comments made by Trevor Timm, who’s the executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation, regarding your likely prosecutions or the consequences of Manning’s verdict for you. He said—although he agreed that the verdict brings the government closer to prosecuting you, he said, quote, “Charging a publisher of information under the Espionage Act would be completely unprecedented and put every decent national security reporter in America at risk of jail, because they also regularly publish national security information.” Julian Assange, your response?

JULIAN ASSANGE: Yeah, I agree. We’ve been saying this for three years now. It’s nice to see, finally, that in the past three months or so the mainstream press in the United States, at least McClatchy and The New York Times—Washington Post has been a bit more problematic—have woken up to the reality of what this case means for all national security reporters and, even more broadly, for publishers.

You know, the approach here has been to smash the insider and the outsider, as it was only one name on the table for an insider, and that was Bradley Manning; it was only one organization as the publisher, the outside force, that’s WikiLeaks, and most prominently represented by me. So in order to regain a sense of authority, the United States government has tried to, rather conspicuously, smash Bradley Manning and also the WikiLeaks organization. At least for WikiLeaks, the organization, it has not succeeded. It will not succeed. It is bringing great discredit on itself. Its desire for authority or perception of authority is such that it is willing to be seen as an immoral actor that breaches the rule of law, that breaches its own laws, that engages in torture against its youngest and brightest. In the case of Bradley Manning, the U.N. formally found against the United States, special rapporteur formally finding that the United States government had engaged in cruel and abusive treatment—cruel and inhumane treatment of Bradley Manning.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Assange, I also want to ask you about BSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, who remains, as you know, at the Moscow airport, who you’re deeply involved with helping to try to find a place of asylum. In a letter sent last week to the Russian minister of justice, the U.S. attorney general, Eric Holder, assured Russia that Snowden will not be executed or tortured if he’s sent back to the United States. Holder wrote, quote, “Mr. Snowden will not be tortured. Torture is unlawful in the United States.” He went on to say, “If he returns to the United States, Mr. Snowden would promptly be brought before a civilian court convened under Article III of the United States Constitution and supervised by a United States District Judge.” Holder also added, quote, “We believe [that] these assurances eliminate these asserted grounds for Mr. Snowden’s claim that he should be treated as a refugee or granted asylum, temporary or otherwise.” Can you tell us what you understand to be the latest situation for Snowden and what your involvement with Edward Snowden is, why he is so significant to you, what his actions have been?

JULIAN ASSANGE: Edward Snowden’s freedom is a very important symbol. Bradley Manning’s incarceration is also an important symbol. Bradley Manning is now a martyr. He didn’t choose to be a martyr. I don’t think it’s a proper way for activists to behave, to choose to be martyrs. But these young men—allegedly in the case of Bradley Manning and clearly in the case of Edward Snowden—have risked their freedom, risked their lives for all of us. That makes them heroes. Now, Bradley Manning has been put into a position, quite unjustly, where he is facing 136 years. That brings disrepute upon the United States government and upon its system of justice. Edward Snowden has seen what has happened to Bradley Manning. The Ecuadorean government, in their asylum assessment of me, looked at what happened to Bradley Manning.

U.S. guarantees about torture mean nothing. We all know that the United States government simply redefines its torturous and abusive treatment of prisoners—stress positions, restriction on diet, extreme heat, extreme cold, deprivation of basic things needed for living like glasses or the company of others—it simply redefines that as not being torture. So, its word is worth nothing, in this particular case. In relation to the death penalty, guarantees about the death penalty have more credence, but we wouldn’t want Edward Snowden to be in a Jack Ruby-type situation. That’s quite a possibility for him, that if he ended up in the United States prison system, that given the level of vitriol that exists against him by the administration, that he would not be safe from police, he would not be safe from prison guards, and he would not be safe from other prisoners. There’s no question that he would not—there’s no question that he would not receive a fair trial.

Similarly, the charges against him are political. There’s only allegations on the table at the moment that he acted for a political purpose: to educate all of us. Those are the only allegations that exist. It is incorrect that extraditions should take place for a political purpose. He’s clearly been exercising his political opinion. But we have seen amazing statements by the White House in relation to Edward Snowden’s meeting with Human Rights Watch, based in New York, Amnesty International, based in London, that that should not have happened, that that was a propaganda platform for Edward Snowden. I mean, this is incredible to see Jay Carney, a White House spokesperson, denouncing Edward Snowden for speaking to human rights groups. Edward Snowden cannot possibly receive a fair judicial process in the United States. Under that basis, he has applied for asylum in a number of different countries. I believe that Russia will afford him asylum in this case, or at least on a temporary or interim basis. And a number of other countries have offered him asylum.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian, what—Julian, what is the problem? Last week, there was breaking news that the Russian—that Russia had granted him temporary asylum, but now it is said that he has never been given those papers, so he can’t leave the—what, the airport lounge.

JULIAN ASSANGE: This is just the media. This is a case where there’s a lot of demand for information, so people just invent it, or they amplify some particular rumor.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Julian Assange, very quickly, before we conclude, the U.S. government now classifies 92 million documents a year—this is an unprecedented number—with over four million people cleared for security clearance. Can you explain what you think the significance of this is and has been for whistleblowers, and what the Manning verdict says to future potential whistleblowers?

JULIAN ASSANGE: Well, the verdict is clearly an attempt to crush whistleblowers. It’s not going to crush whistleblowers. The problems that exist in the security state in the West, and a few other countries, as well, as bad as they have ever been, they’re rapidly accelerating. We now have a state within a state in the United States. There are more than five million people with security clearances, more than one million people with top-secret security clearances. The majority of those one million people with top-secret security clearances work for firms like Booz Allen Hamilton and so on, where they are out of the Freedom of Information Act, where they are out of the inspector general of intelligence’s eye. That is creating a new system, a new system of information apartheid, a new asymmetry of information between different groups of people. That’s relating to extensive power inequalities with the—if you like, the essence of the state, the deep state, the intelligence community, lifting off from the rest of the population, developing its own society and going its own way.

And we have a situation now where young people, like Edward Snowden, who have been exposed to the Internet, who have seen the world, who have a perspective, who have seen our work, the work of—allegedly of Bradley Manning and others, don’t like that. They do not accept that. They do not accept that the U.S. Constitution can be violated, that international human rights law norms can be conspicuously violated, that this information apartheid exists. That system cannot continue. We even saw Michael Hayden acknowledge that in an interview in Australia recently, that in order to function, the National Security Agency, the CIA, and so on, has to recruit people between the ages of 20 and 30. Those people, if they’re technical and they’re exposed to the Internet, they have a certain view about what is just. And they find that they’re—in their jobs, the agencies that they work for do not behave in a legal, ethical or moral manner. So the writing is on the wall for these agencies.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian, I know you have to go, but I want to quickly ask one more time: What does the verdict in the Bradley Manning case—faces 136 years in prison—mean for you? Your name and WikiLeaks came up repeatedly throughout the trial. We know of a grand jury investigation of you and WikiLeaks in Virginia. Do you in fact know that there is a sealed indictment for you? And what does this mean for your time at the Ecuadorean embassy and your chance of getting out?

JULIAN ASSANGE: Based on conversations with the DOJ between my U.S. lawyers and the DOJ spokespersons, we know a lot. We know that Neil MacBride, the Virginia DA, has the grand jury process. My U.S. lawyers believe that it is more probable than not that there is a sealed indictment. It’s the only explanation for the DA behavior. The DOJ has admitted that the investigation against me and WikiLeaks proceeds.

In relation to the Manning verdict, we will continue to fight that. We have a lot of people now in his coalition. Bradley Manning’s support team has been great. The Center for Constitutional Rights also have been excellent, Michael Ratner, who’s been on your own program. That team understands what is going on; has been deployed, to a degree, to defend Mr. Snowden in public; and presumably, when the time comes, will also defend us. I am completely confident that the U.S. will not succeed in extraditing me, because I have asylum at this embassy. In relation to the broader attack on the rest of our staff, that’s still very much in the fight, but we’re not going to go down easy.

AMY GOODMAN: We just have this breaking news, which says that the Obama administration will make public a previously classified order that directed Verizon Communications to turn over a vast number of Americans’ phone records, according to senior U.S. officials. The formerly secret order will be unveiled before a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that’s scheduled to begin in 20 minutes from our broadcast time right now. The order was issued by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court to a subsidiary of Verizon in April. Your response to that, finally, Julian? And then we’ll let you go.

JULIAN ASSANGE: Well, Edward Snowden already made the order public, so, I mean, this is absurd. This is like our release of Guantánamo Bay documents and other documents. These have already been made public, and now the administration is going to apparently wave some magical pixie dust to remove the contaminant of it being formerly classified by the administration. So, I mean, here we have an example that there’s actually no disclosure before the public, until there is unauthorized disclosure before the public. If I’m incorrect, and this is not the document that Snowden has already revealed—

AMY GOODMAN: It is. It is the document.

JULIAN ASSANGE: Yeah, so, I mean, it’s—there’s some magical-like process going on here where there’s holy documents and unholy documents. Holy documents are documents that this classification state within a state, five million people with security clearances, have somehow done something, to sprinkle some absurd holy water on. These are just pieces of paper with bits of information on them and bureaucrats putting a stamp on them. That’s the reality. We’ve got to remove this religious national security extremism. It is a new religion in the United States and in some other countries. It’s absurd. It’s ridiculous. It needs to go.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Assange, we want to thank you for being with us, founder and editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks, granted political asylum by Ecuador last year and sought refuge over a year ago at the Ecuadorean embassy in London.

This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. To read a transcript, listen to or watch this interview, you can go to our website at democracynow.org. When we come back from break, we’re going to Fort Meade, where Bradley Manning has been court-martialed, the sentencing beginning today, the sentencing phase of his trial. We’ll speak with one of the few reporters, independent reporters, to have spent every day in the courtroom, or the media center right next to it, to report to the rest of the world what was happening to Bradley Manning. We’ll be joined by Alexa—we’ll be joined as soon as we come back. Stay with us.

Media Options