Guests

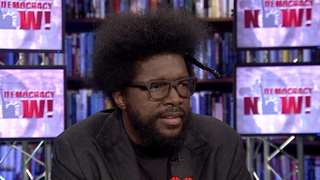

- Ahmir "Questlove" Thompsondrummer and co-founder of The Roots, the legendary hip-hop group and house band on NBC’s Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. He is also a DJ, music scholar and author of the new memoir, Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove.

On the heels of this week’s historic ruling declaring the “stop-and-frisk” tactics of the New York City Police Department unconstitutional, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of the Grammy Award-winning band The Roots joins us to talk about his own experiences being racially profiled by police. Questlove describes the first time he was harassed by police, as a young teenager in Philadelphia on his way to Bible study, to the most recent: being pulled over in his car by the NYPD two weeks ago, despite being one of the most acclaimed artists in hip-hop. He also discusses the message he took away as an African-American male from the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin: “You’re guilty no matter what, and you just now have to figure out a way to make everyone feel safe and everyone feel comfortable, even if it’s at the expense of your own soul.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This week is widely celebrated as the 40th birthday of hip-hop music and culture. On August 11, 1973, the New York DJ Kool Herc held his first block party in the Bronx. It was at these parties where Kool Herc pioneered a revolutionary technique: Using two turntables and two copies of the same vinyl record, Herc isolated instrumental portions of funk, soul, Latin and even rock songs to create the elongated beats that form the basis of the hip-hop sound. Combined with lyrical rhyming over-top, rap music was born. This past week, Kool Herc was joined by a number of hip-hop legends in New York’s Central Park for a 40-year celebration.

Well, today we are joined by one of hip-hop and popular music’s most eclectic and influential voices, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson of The Roots. Born in West Philadelphia and immersed in music from an early age, Questlove rose to fame as the co-founder and drummer for The Roots. While most rap music comes from drum machines and samplers, The Roots create their sound through live instrumentation. Steeped in the jazz and soul tradition that influenced hip-hop’s rise, The Roots have helped define a new generation of neo-soul and conscientious rap.

Today, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson and The Roots are well into their third decade. They’re the house band on NBC’s Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, with Questlove serving as musical director. Questlove is also a highly prolific music producer and composer, working with artists including D’Angelo, Common, Al Green, and Betty Wright. He’s also a highly in-demand DJ. Questlove is also now an author, out with a new memoir, Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove.

Well, on Tuesday, Democracy Now!'s Aaron Maté and I sat down with Questlove to discuss his new book, the state of hip-hop after 40 years, and the killing of Trayvon Martin. But first, on the heels of this week's historic ruling declaring the stop-and-frisk tactics of the New York Police Department unconstitutional, I asked Questlove to talk about his own experience with racial profiling. He talked about his first time being stopped as a teenager in Philadelphia.

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: There was a point where I was coming home from—from Bible study, like teen Bible study on a Friday night, and there was a Tower Records on South Street. And a friend of mine wanted to purchase U2’s The Joshua Tree album, which just came out. And they were coming to Philly at RFK Stadium, so he wanted to, like, study the record and know all the material before they came, and so we went and purchased The Joshua Tree. And we were driving home, and then, seconds later, on Washington Avenue in Philly, like, cops stopped us. And he was holding a gun on us.

And there’s nothing like the first time that a gun is held on you. Like, we’re 16, mind you, like 16, 17 years old. And, you know, I just remember the protocol. I remember my father telling me, like, “If you’re ever in this position, you’re to slowly keep your hands up.” I mean, he did it in sort of a humorous way that Richard Pryor did. You know, Richard Pryor told a joke of, whenever you’re stopped, “Yes, officer, my hands are on the steering wheel.” You know, it was that type of thing. I remembered that lesson. So, my friends didn’t know that, so they just thought that it was normal. And I was like, “Yo! Get your hands up! Get your hands up!” Like, how I knew that was the protocol at that young age, I mean, it’s probably a sad commentary, but it was also, you know, a matter of survival. And so—

AMY GOODMAN: You know, Judge Shira Scheindlin just handed down the decision saying “stop and frisk” is unconstitutional in New York, 700,000 especially—

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: I was—I was highly shocked that—you know, that’s something that just came out of left field, because I, too, was wondering, you know, will “stop and frisk” just be just a way of life? I mean, just two, three weeks ago—I mean, I wasn’t frisked, but I was—I definitely know that was stopped for, you know, unknown reasons, that I was just the wrong person in the wrong automobile.

AMY GOODMAN: Two weeks ago?

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah, I get stopped all the time. I mean, I just—it’s just to the point—

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us about the last time.

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: I was leaving my Thursday night residency. I do a regular DJ night at Brooklyn Bowl in Williamsburg, and right before we got on the Williamsburg Bridge, we got pulled over. They walked up, asked to see license and registration. And it was like four of them with flashlights everywhere. And I played a risky card: I was like—I pulled this out of my backseat and was like, “This is me,” you know, hoping. And nine times out of 10 when I’d play that card, it never works.

AMY GOODMAN: Showing your book, you mean.

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah, you know, because they wanted to know, like, well, you know, “Are you in a cab? You know, is this a cab? Where’s your New York taxi license?” I have my own car, and I have my own driver. And so, by the questions they were asking, I knew they didn’t know who I was. So, to them, it’s like, “OK, like, why are you sitting in the backseat like a—like a don, and you have your driver up there?” And, you know, so I showed them the book, and they looked, and they kind of had a meeting for five minutes. And then, it was like, “Oh, OK, you can go.” And phew, you know, but this happens all the time.

AMY GOODMAN: How many times would you say you’ve been stopped?

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Probably, in my lifetime, I’ve been stopped—one, two, three—I mean, the memorable ones are probably six times. But it’s definitely in the twenties and thirties. I mean, probably, since 1994, twenties and thirties. The worst one was after Super Tuesday in Orange County. I was campaigning for Super Tuesday, and—

AMY GOODMAN: For Obama?

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: For Obama. And after it was over, a friend of mine, Jurnee Smollett, who’s an actress on True Blood, she and I were done campaigning, and we decided to see a movie. After the movie, we went to Borders to get—I wanted to get a housewarming gift for my manager. And we pulled over. I pulled over to take a phone call from my manager, because, you know, I thought, being a law-abiding citizen, you’re not supposed to drive and talk. So I pulled over, talked, finished the conversation, pulled off. Five cars stopped us, and pretty much that was like the—that was the most humiliating experience, because, like, we had to get out the car. They made us spread on, you know, the car. They searched the car. We sat in the back of the—not their paddy wagon, the—

AMY GOODMAN: Cruiser.

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah, their car. And the whole time I was thinking, like, “God, please don’t look in the trunk.” Like, first of all, I felt like a criminal already, like, OK, I’ve got stuff in the trunk. But the stuff I had in the trunk were psychology books and some Scrabble games. And in my head, I was like, there’s no way that they’re going to believe that that stuff belongs to me. Like, there’s no way that they’re—and so, the whole time I was just like, “God, please don’t. Please don’t.” She was trying to get like her camera phone. She’s like, “This is unconstitutional! They’re not—this is an illegal search. They’re supposed to have a protocol for”—you know, so that—you know, I’ve been—this is like the night before the Grammys, the night before the Grammys in 2010, when I won. So, it’s like, this happens all the time.

AMY GOODMAN: So, with all these examples you’ve given of being stopped, whether at the airport or in a car, by cops, can you explain—because we hear, legally—I mean, now it’s been ruled unconstitutional, “stop and frisk” in New York—but what it does to you?

AHMIR “?UESTLOVE” THOMPSON: It is absolutely probably the most humiliating, lowest, lowest feeling a human being can have. Twice this happened in front of dates. And all I kept thinking about was like, man, like, nothing’s more emasculating than to be emasculated in front of a girl that you like. You know, like there’s just no coming back from that. And it’s sort of like an unspoken thing, like I always felt like, even afterwards, like there’s this unspoken cloud of the question of my manhood, because—you know, that’s why I’m often shocked when I see footage of people and they talk back to cops. Like, I want to do that, but it’s like—you know, even watching Fruitvale, like I was like, “No, don’t—don’t—like, just get on your knees! Just don’t—you know, you can die.” And that’s—it’s the most humiliating, emasculating feeling I’ve ever had. That’s—I only feel low when that happens, you know, even—even if it’s playful.

In Philly, whenever we finish a Roots album, I give it the car test. So, even driving up and down Broad Street in Philadelphia, I once got stopped three times. And, you know, the first two times, they were just like—they looked, they were just like, “Oh, it’s you.” They let me go. Third time, this guy, “Oh, man, it’s you!” And then I felt safe enough to sort of have casual banter with him. I was like, “This is the third time I’ve been stopped. Like, what’s going on here?” And he was like, “Well, you know, I mean, you’re kind of in Temple University’s neighborhood.” And I was like, “Yeah? And?” He’s like, “Well, look at the car you’re in.” I drive a Scion. And my logic for getting a Scion was like don’t get a flashy—like, I come from the '80s, so in the ’80s, when you saw someone in a BMW, in a Mercedes, they automatically got pulled over, because they were a drug dealer. So I thought, OK, I'll get a Scion—well, first of all, it was free; it was given to me. And it was boxy; it was afro-friendly, like it didn’t smoosh my afro down, and so it’s a comfortable car. I like it. He said, “You know, in this, you kind of look like you stole it from a college student.” And I was like, “Oh, well, OK, I get it.” So, in even choosing the car in my mind that would sort of not put me in that position, I actually wound up putting me in that position by driving that car, because he said, “If you were in a SUV, we would have just thought you were one of the Philadelphia Eagles or something.” Like, oh, OK, that’s the car you belong in.

AMY GOODMAN: And you mean by “street test” that you play your album in the car?

AHMIR “?UESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah, well, you know, most people, when they finish their records, they try and find a really good speaker system. When you mix your records, you do it on horrible speakers, so that way, if it sounds great on horrible speakers, it’ll sound great elsewhere. So when you finish your record, the first place you want to take it to is to a good car system. I mean, mine is not—I mean, it’s satisfactory, but, you know, I just wanted to drive around with it. I always do it, with every Roots album. I just drive around for five hours, making sure that I like the mix and I’m fine with it. I just happen to drive between the hours of 2:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m., and, you know, that was another unfortunate circumstance I found myself in. But even then, it’s just like, what do you do? Do you—I mean, how much more can I play it safe? Like, I’m already like taking—purposely taking myself out of situations because I want to avoid that. But I don’t know how much more I can—I can suppress myself to not seem like a threat or be a threat. So…

AARON MATÉ: After the George Zimmerman verdict last month, you wrote a post that was widely circulated. You said, “I don’t know how to not internalize the overall message this whole Trayvon case has taught me: You ain’t [bleep].”

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah.

AARON MATÉ: “That’s the lesson I took from this case. … I guess I’m struggling to get at least 1 percent of this feeling back, from all this protective numbness I’ve built around me, to keep me from feeling.” What did you mean by “protective numbness”?

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: You know, I think there’s just a bit of our soul that sort of just melts away when things like this happen. I mean, first of all, you internalize it. Like, as I watched the case, I mean, I identified with Trayvon Martin, like I felt like, OK, that would have been me in that situation. I mean, there’s definitely been times where I’ve been watching either a sporting event or the Grammys or any sort of television event, and then I’d be the person that would run to the store to get something. Like, that could have easily been me. I live in hoodies. I opened a hoodie shop. I have a hoodie shop that sells nothing but hoodies. Like, I love hoodies, because it gives me anonymity, like I get to go to movies, and no one bothers me. Like, if I go looking like this all the time, then it’s going to be problematic. And so—

AMY GOODMAN: Just for people listening on the radio and don’t know Questlove—

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Oh, what I look like.

AMY GOODMAN: Yeah, he’s got pretty distinctive hair. It may not be the psychedelic hair on Mo’ Better Blues.

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: But it’s sort of just like that.

AHMIR ”QUESTLOVE” THOMPSON: Yeah, I’m kind of—I’m Captain Obvious. And so, when the verdict was handed down, you know, I just felt like—half of me, I instantly felt like, well, yeah, I knew that was going to happen. But then the other half of me was upset that I had just resigned to that fact. And, you know, because I was on an international flight—I was in Holland the day that the verdict was handed down, so that whole eight-hour trip on the plane, I just felt like, oh, well, you know, nothing matters anymore, like this really—life doesn’t matter, like you’re guilty no matter what, and you just now have to figure out a way just to make everyone feel safe and everyone feel comfortable, even if it’s at the expense of your own soul. And so, in talking to my manager about it, who was the first human I talked to when I got off the plane, you know, he, too, was like sort of echoing that, like, “Well, why are you acting shocked? Like, you knew exactly this was the outcome. Like, why are you shocked? Like, why are you letting it get to you?” I just felt like I was going to explode right there, so I just—I had to talk to somebody, and so I just started to write, for no particular reason. And one person asked if they could, you know, put this on their blog, and then it kind of spread, and the ripple effect happened.

AMY GOODMAN: Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, drummer and co-founder of The Roots, the legendary hip-hop group and house band of NBC’s Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, soon to be The Tonight Show. He’s also a DJ, music scholar, and author of the new memoir, Mo’ Meta Blues. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back with the conversation on this 40th anniversary of hip-hop in a minute.

Media Options