Related

Topics

Guests

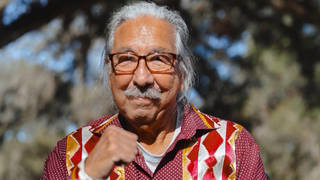

- Mac McClellanda contributing reporter to Mother Jones magazine. Her cover story last June was headlined “I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave: My Brief, Backbreaking, Rage-Inducing, Low-Paying, Dildo-Packing Time Inside the Online-Shipping Machine.”

As Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos buys The Washington Post, we look at life inside the factories that make online companies like Amazon run. Last week, President Obama delivered a major speech on jobs at an Amazon warehouse in Chattanooga, Tennessee. We speak to journalist Mac McClelland, who went undercover and got hired at an unnamed online fulfillment center using the model Amazon has perfected. The result was her cover story for Mother Jones magazine last June, “I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave: My brief, backbreaking, rage-inducing, low-paying, dildo-packing time inside the online-shipping machine.”

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We continue now to look at the track record of Amazon.com, the company founded by Jeff Bezos, who on Monday purchased The Washington Post. The company was also in the news earlier this month when President Obama delivered a major speech on jobs at an Amazon warehouse in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Obama offered to cut corporate tax in return for new government programs to create jobs.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: So, here’s the bottom line. If folks in Washington really want a grand bargain, how about a grand bargain for middle-class jobs? How about a grand bargain for middle-class jobs? Here’s the bottom line. I’m willing to work with Republicans on reforming our corporate tax code, as long as we use the money from transitioning to a simpler tax system for a significant investment in creating middle-class jobs. That’s the deal.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: President Obama’s comments were part of a White House effort billed as an attempt to take on widening U.S. inequality. But critics say creating more jobs like those at the Amazon warehouse where he spoke would do little to achieve this goal.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined by reporter Mac McClelland, who went undercover and got hired at an online fulfillment center using the model Amazon has perfected. The result was her cover story for Mother Jones magazine last June, headlined “I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave: My Brief, Backbreaking, Rage-Inducing, Low-Paying, Dildo-Packing Time Inside the Online-Shipping Machine.”

Mac McClelland, welcome to Democracy Now! So tell us, where did you work?

MAC McCLELLAND: I—actually, on the record, for legal reasons, I can’t say where I worked, because there’s a precedent to side with companies in cases where companies sue journalists who have gone undercover.

AMY GOODMAN: So you called it “Amalgamated Product Giant Shipping Worldwide Inc.,” the place that you worked. Tell us where you worked, at least, you know, physically, the state you were in, and then tell us about, well, the state you were in, I guess, psychologically and physically. What happened at the plant?

MAC McCLELLAND: I can tell you that I was west of the Mississippi and sort of in the middle of no place. A lot of these warehouses are in kind of industrial wasteland areas, and people commute from nearby cities from all over. The warehouse that I was working in had thousands of people in it. And since it was the run-up to Christmas, they were hiring 4,000 additional temporary workers just for the last four months of the year.

So, basically, from the moment I arrived in town, even before I got to the warehouse, I stopped by the local Chamber of Commerce, and they told me, “Don’t start crying, and don’t take anything that happens to you personally, because it’s a very ugly scene in there. And there’s lots and lots of people who would be willing to take your job, because the economy is so bad. So, basically, put up with whatever they throw at you, and, you know, leave your dignity at the door.” And so, that’s what I did, and that’s what everybody else there did every day.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Mac, could you talk about what prompted you to get this temporary job? How did you become interested in conditions in these kinds of warehouses?

MAC McCLELLAND: I had done another story about basically the death of the middle class in Ohio in the run-up to Governor Kasich’s, you know, budget slashes that he was doing, and so I stopped by a warehouse that one of my ex-girlfriends actually from college was running. I didn’t have any agenda. I just went in there to look at it, and I was shocked at the conditions. And I come from a labor background. I worked for years and years and years in moving and storage. Actually, I was a mover and worked in warehouses and things like that. And I couldn’t believe how tough and dehumanizing and low-paying these positions were. And my friend, who is a really nice person, was being sort of a monster. I was there for 20 minutes, and she was firing people for going to the bathroom and for talking to each other, even though they were continuing to work while they did it. And those were the orders that she had from up top, and she just—if she wanted to keep her job, she had to enforce them. And so, since this sector is gigantic and is continuing to grow and will continue to grow, we decided to devote a whole story to it.

AMY GOODMAN: So, tell us—take us inside the plant. Tell us about your first day and the days beyond that.

MAC McCLELLAND: Well, basically, every day is running, from the moment you get in the door. There are very specific goals, and they’re very, very fast and very hard-to-meet goals. So you walk in the door, you grab a little hand-held scanner. I was what’s called a picker, which is the person who actually retrieves the items that you order online. And these are hundreds of thousands of square feet, these warehouses, just absolutely enormous. And you have a little scanner that tells you where in the warehouse you have to go. There’s a map on you ID badge. And it tells you how many seconds they want you to take to get there. So, you know, a Barbie will pop up, and you have 20 seconds to traverse this ground, and you run to where the place is on the shelving, and you’re, you know, picking through items as fast as you can, and you grab the Barbie, and you scan it, and you put it in a tote. And then your next thing pops up, and you have 15 more seconds. And that is just relentless. We had minimum 10-hour shifts when I was there. And there’s people walking around telling you how close you are to making your numbers, or not making your numbers in a lot of cases. And so, someone comes up to you every couple hours and says, “You’re making 70 percent of your goals. You’re doing a bad job. You’re going to have to pick it up.” And so you’re counseled sort of incessantly on your pace. And so you run back and forth to the lunch room. You have to go through metal detectors. You have to wait in line to go to the bathroom, eat some food really fast, and run back to your station. And that’s it, just over and over and over again.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, others have described—have reported on conditions you describe, as well. I want to read from a story headlined “Inside Amazon’s Warehouse” that was published in 2011 by The Morning Call newspaper of Allentown, Pennsylvania. They visited Amazon.com’s Lehigh Valley warehouse, where books, CDs and various other products are packed and shipped to customers. The article noted that, quote, “Workers said they were forced to endure brutal heat inside the sprawling warehouse … During summer heat waves, Amazon arranged to have paramedics parked in ambulances outside, ready to treat any workers who [were] dehydrated or suffered other forms of heat stress. Those who couldn’t quickly cool off and return to work were sent home or taken out in stretchers and wheelchairs and transported to area hospitals. And new applicants were ready to begin work at any time.

“An emergency room doctor in June called federal regulators to report an 'unsafe environment' after he treated several Amazon warehouse workers for heat-related problems. The doctor’s report was echoed by warehouse workers who also complained to regulators, including a security guard who reported seeing pregnant employees suffering in the heat,” end-quote.

That’s from a 2011 story by The Morning Call newspaper of Allentown, Pennsylvania, about Amazon.com’s Lehigh Valley warehouse. Mac McClelland, your comments on that? Compare that to your own experience in the warehouse you worked in.

MAC McCLELLAND: Well, I was working in November, and so it was—instead of being really hot, it was freezing inside the warehouse that I was in. And they actually had had a fire alarm a few days before I got there, and everyone had been evacuated. They had been stripped down to their T-shirts and tank tops, because they had been running so hard inside the warehouse, even though it’s cold, that they just stood in the snow, while it was snowing on them for an hour, while they waited for, you know, permission to go back inside. But they were telling me that I should be grateful that I wasn’t working there in the summer, because the summer was even worse.

And the warehouse that I visited in Ohio, that was in June, and there were people working in the backs of trucks. The people who had to load trucks were standing in these tractor-trailer containers, just baking in the parking lots under the sun for hours and hours at a day. They had like a couple little fans blowing on them. They won’t air-condition the warehouses because it’s too expensive. They don’t heat the warehouses because it’s too expensive.

And another problem with the cold that I was having, and that everyone was having where I was working, was that it’s very dry. So, with the dryness and with the metal shelving units everywhere, there’s a lot of electronics in there, with the conveyor belts running and fans and things like that, so there’s actually a buildup of static electricity all the time. And so, I realized one day, especially when you’re assigned to books—I was assigned to pack books—when you—with the paper, it’s even drier in that sector. And when you’re running around on that floor, you’re gathering up all this static electricity, and when you touch the metal shelves to grab whatever the item is, it shocks you really hard in your hand. One of my co-workers actually had leaned a little bit too close to one of the shelves when he was picking books, and it shocked him in his forehead and sort of stunned him back for a second. So, I think all weather conditions are probably unpleasant in one form or another in those warehouses.

AMY GOODMAN: Whether or not you worked at an Amazon house, it was certainly an Amazon model of a warehouse. Your response to President Obama in Chattanooga, Tennessee, at the opening of this new plant? I mean, we are talking about thousands of jobs, Mac.

Mac, can you—can you hear me? It sounds like we’ve just lost the IFB line for a second for her to be able to hear that question. You can go to democracynow.org to see the full conversation today on this segment and every other, and we’ll also be doing a web exclusive on FCC regs of public access TV stations, so check our website there. Let’s see if Mac can hear us in just one second. Mac McClelland is the contributing reporter to Mother Jones magazine, whose cover story was headlined “I Was a Warehouse Wage Slave: My Brief, Backbreaking, Rage-Inducing, Dildo-Packing, Low-Paying Time Inside the Online-Shipping Machine.” We’re going to have to leave it there, but we’ll continue the conversation with her, and we’ll post it online.

Media Options