Guests

- Malik Rahimone of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party, and introduced the Angola Three members to the party. He is also co-founder of the Common Ground Collective, which helped bring thousands of people from all over the world to help rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. In 2008, he was a congressional candidate for the Green Party.

- Jackie SumellNew Orleans-based artist behind “Herman’s House,” a collaboration with long-term solitary confinement prisoner and former Black Panther, Herman Wallace, a member of the Angola Three.

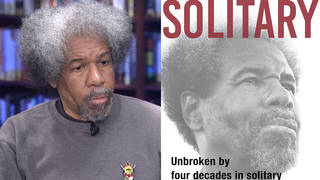

Angola prisoner Herman Wallace is dying of liver cancer after 42 years in solitary confinement. A member of the so-called Angola Three, Wallace and two others were in jail for armed robbery, then accused in 1972 of murdering a prison guard at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola prison. The men say they were framed because of their political activism as members one of the first prison chapters of the Black Panther Party. Wallace’s supporters say he has just days to live, but his requests for compassionate release has so far gone unanswered. We speak with Jackie Sumell, a New Orleans-based artist behind “Herman’s House,” a collaboration with Wallace, which is the subject of a new documentary by the same name. “I’m not sure in the state of Louisiana if compassion is part of the vocabulary of those who are in power. I always felt that compassionate release, or asking for compassionate release, was important in terms of a multipronged effort to have Herman released,” Sumell says. “But there’s been 42 years of the state continuing to deny Herman’s due process. It’s incredible. He’s the longest known serving in solitary confinement in the United States.” We are also joined by Malik Rahim, one of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party and a co-founder of the Common Ground Collective, which helped bring thousands of people from all over the world to help rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re on the road in New Orleans, Louisiana. We’re broadcasting from New Orleans public television station WLAE. We turn now to look at the case of a man who’s spent more than 42 years in solitary confinement in Louisiana, believed to be one of the longest-serving prisoners who served on death row for that amount of time. He is dying now of liver cancer. His supporters are pleading for his compassionate release.

I’m talking about Herman Wallace, a member of the so-called Angola Three. He and two others were in jail for armed robbery, then accused in 1972 of murdering a prison guard at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola. The men say they were framed because of their political activism as members one of the first prison chapters of the Black Panther Party. Herman Wallace is now 71 years old in the late stages of liver cancer. Robert King Wilkerson was released in 2001 after 29 years in solitary confinement. The third of the Angola Three, Albert Woodfox, remains in prison and says he’s been subjected to strip searches and anal cavity searches as often as six times a day.

Well, as Herman Wallace faces the end of his life, we’re joined now by two people. But first I want to turn to a clip from a new film about Herman’s collaboration with one of our guests. Twelve years ago, artist Jackie Sumell began writing to Herman Wallace, and one day she asked him, “What kind of house does a man who has lived in a six-foot-by-nine-foot box for over 30 years dream of?” Wallace wrote back with a description, and soon afterward Jackie made a commitment to build the house so Herman could either live in it upon his release, or so it could serve as a symbol of survival and hope. The two have often spoken by phone in between their visits, though Herman is now too weak to speak anymore. The calls are part of the story documented in a new film called Herman’s House that just premiered on PBS on POV. In this clip, it was Herman who comforts Jackie after the Louisiana Court of Appeals just turned down his latest appeal.

HERMAN WALLACE: Jackie?

JACKIE SUMELL: Yes.

HERMAN WALLACE: What’s the matter?

JACKIE SUMELL: Nothing.

HERMAN WALLACE: I’ll see you tomorrow, right?

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah.

HERMAN WALLACE: Jackie.

JACKIE SUMELL: What?

HERMAN WALLACE: Look, this is a struggle, kiddo, all right? You hear me?

JACKIE SUMELL: I hear you.

HERMAN WALLACE: This is a struggle, and it’s worth it. It’s part of that. You have to roll with that. And it should make us stronger, right?

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah, well—

HERMAN WALLACE: So, please, come on, last thing you want to feel is down. You are too much of a strong, happy person for that. And I think as long as you know that I’m OK, I think that’s all that should matter, right?

JACKIE SUMELL: That’s correct.

HERMAN WALLACE: Right, and I’m OK.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Herman Wallace speaking with our guest today, Jackie Sumell. She is the New Orleans-based artist behind Herman’s House, a collaboration with Herman Wallace and the subject of this new documentary by the same name that premiered on PBS POV this summer.

We’re also joined here in New Orleans by Malik Rahim, one of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party. He introduced the Angola Three members to the party in prison. He is also co-founder of the Common Ground Collective, which helped bring thousands of people from all over the world to help rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. In 2008, Malik ran for Congress as a Green Party candidate.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now!

We did submit a request to interview Herman Wallace after he was removed into the prison hospital, but we were told James LeBlanc, secretary of the Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections, had, quote, “denied similar requests in the [last] few weeks and he did not want to make an exception in this case.”

Jackie Sumell, Malik Rahim, welcome to Democracy Now! Jackie, you just came back from seeing Herman yesterday. What is his condition?

JACKIE SUMELL: Thank you so much, Amy. It’s an honor to be here. I had an opportunity to visit with Herman yesterday. And it’s really obvious, beyond a reasonable doubt, that we are days, if not hours, from watching the state of Louisiana kill another innocent man behind bars.

AMY GOODMAN: Was he able to speak?

JACKIE SUMELL: He’s still able to speak a few words. Yesterday he asked me to put his cap on. The inmates had just bathed him, and he was without his cap. He was cold. His words are few and far between. He sleeps most of the time. His belly is distended. He’s incredibly uncomfortable. And I think these will be his last few breaths before he joins the ancestors.

AMY GOODMAN: Compassionate release, is it a possibility?

JACKIE SUMELL: I’m not sure in the state of Louisiana if “compassion” is part of the vocabulary of those who are in power. I always felt that compassionate release or asking for compassionate release was important in terms of like a multipronged effort to have Herman released. But there’s been 42 years of the state continuing to deny Herman’s due process, so—

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, 42 years in solitary confinement.

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah, it’s incredible. It’s incredible. He’s the longest known serving in solitary confinement in the United States. And one of the things I think is important to illustrate, or that Herman’s fight has been, is to illustrate the fact that the U.S. still employs the use of solitary confinement. There’s over 80,000 inmates at any given time, and, as you said, the highest incarcerator in the world, that are in solitary confinement, a six-foot-by-nine-foot cell, a minimum of 23 hours a day. And it’s an indefinite period that most people are in solitary confinement.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to play a clip of Teenie Verret, the widow of the murdered prison guard. She was just 17 when her husband, Brent Miller, was stabbed to death in 1972. This is the murder that Herman Wallace was convicted of. This is Teenie Verret from the documentary In the Land of the Free.

TEENIE VERRET: I’ve been living this for 36 years. There’s not a year that goes by that I don’t have to relive this. And it just keeps going and going. And then these men, I mean, if they did not do this—and I believe that they didn’t—they have been living a nightmare for 36 years.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Teenie Verret saying, if they did not do this—and she doesn’t believe that Albert Woodfox and Herman Wallace did this—then they should not be serving these sentences.

JACKIE SUMELL: You know, there’s tens of thousands of people who believe that they did not do this. You know, I have absolutely no doubt that Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox and obviously Robert King are innocent.

AMY GOODMAN: And Robert King is out.

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah, Robert King was released in 2001, under investigation for the same crime and had just served 29 years of solitary confinement for a crime he didn’t commit.

AMY GOODMAN: Malik Rahim, you are well known in this area. Yes, you ran for Congress. You helped save New Orleans after the Hurricane Katrina. You knew these men in prison. They say they were framed for this murder because of their political organizing. You were involved with that political organizing.

MALIK RAHIM: Yes. First I want to say that compassionate—compassionate justice do not exist in Louisiana. Their confinement is based upon what the state call Black Pantherism, you know, that the Black Panther Party was just an organization of blacks who hated whites and was bent on killing. And that’s what they have based their conviction on. They stay in solitary, have been, basically because of that Black Pantherism. It have been used throughout their 41 years. Burl Cain—they have repeatedly said that even if they was found innocent, he would still be keep them in solitary, because of Black Pantherism.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to a clip of Herman Wallace in his own words describing the impact of solitary confinement on his body. This is from the film that just premiered this summer on POV called Herman’s House.

HERMAN WALLACE: Being in a cage for such an extended period of time, it has its downfalls. I mean, you may not feel it, you may not know it, you may think that you’re OK, and you just perfunctorily move about, you know. However, when you was removed from out of that type of situation and placed in an open environment where, you know, you’re even breathing that oxygen and it’s getting into your lungs and you’re feeling something growing within you, and—you begin to develop a different mode within your body. I even watched my body. I’ve looked in the mirror, and I’ve seen muscles and [bleep] begin to pop out there. I began to run even faster and [bleep]. And I’m saying, “Whoa, what the hell is going on here?” Much was preserved. But then I got locked up again after eight months. And being locked up like that, the whole body just got confused.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Herman Wallace describing solitary confinement. Jackie, you’ve talked to him a great deal about this.

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah. I mean, one of the things I want to be clear about, Amy, is that the state of Louisiana has never relied on lethal injection to kill its incarcerated. Right? There’s a history, a documented history, of neglect, abuse, cruel and unusual punishment, and what I would call lethal injustice, which is the denial and delaying of due process or our so-called constitutional guarantees. And within that framework, you have men who are spending 40 years in solitary confinement.

AMY GOODMAN: Jackie, you did something unbelievable with Herman Wallace. You wrote to him and said you wanted to build a house that he would design?

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah, it’s unusual.

AMY GOODMAN: What was the question you put to him?

JACKIE SUMELL: I was at Stanford University, a full ride with stipend to study art, when I met Robert King. And it was really hard for me to—

AMY GOODMAN: One of the Angola Three, the one who was released.

JACKIE SUMELL: The one who was released. It was just about two months after he was released. And it was really hard for me to contextualize my relative privilege to the situation that Herman and Albert were still enduring. And I knew that I had to do something. And, you know, my greatest tool is my imagination. So I asked Herman what kind of house he dreams of after spending then 30 years in solitary confinement in a six-foot-by-nine-foot box. And I did that with the hope that this would be the opportunity for him to just use his imagination to get out of that box.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to play a clip of Herman from Herman’s House where Herman Wallace describes what sort of details he’d like to see as part of his house.

HERMAN WALLACE: Jackie, in your letter you asked me what sort of house does a man who lives in a six-foot-by-nine-foot cell dream of? In the front of the house, I have three squares of gardens. The gardens are the easiest for me to imagine, and I can see they would be certain to be full of gardenias, carnations and tulips. This is of the utmost importance. I would like for guests to be able to smile and walk through flowers all year long.

AMY GOODMAN: This is not just a figment of Herman Wallace’s imagination, Jackie. You are building this house. You’re here buying property for this house, as Herman Wallace lays dying in a prison hospital.

JACKIE SUMELL: Yeah, I made a commitment to Herman over 10 years ago that I would build his dream house, with the intention, as you said at the beginning of this segment, that this house is a testament to his imagination, to the triumph of the imagination, and to Herman’s legacy, which will outlive his flesh and bones—you know, Herman’s legacy, his commitment to the people and the story of his injustice. And it’s important to build this house in the incarceration capital of the world.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to the end of Herman’s House, the documentary, where Herman Wallace describes a dream. Listen carefully.

HERMAN WALLACE: I’ve had a dream where I got to the front gate, and there’s a whole lot of people out there. And you ain’t going to believe this, but I was dancing my way out. I was doing the jitterbug. I was doing all kind of crazy, stupid-ass [bleep], you know? And people was just laughing and clapping and [bleep], you know, until I walked out that gate. And I remember that dream, and I turn around, you know, and I look, and there are all the brothers in the window waving and throwing the fist sign, you know? It’s—it’s rough, man. It’s so real, you know. I can feel it even now, you know, talking about that.

AMY GOODMAN: Herman Wallace, describing his dream of freedom. Malik Rahim, your thoughts as we end today, as, well, we don’t know how many minutes or days Herman Wallace has left?

MALIK RAHIM: I believe that this is one of the saddest occasions in my life. It wouldn’t have been a Common Ground if it wouldn’t have been the Angola Three. And if it wouldn’t have been a Common Ground, then the over 200,000 people that we serve in direct services, what would have happened to them? You cannot say that justice prevail when you have individuals that, under the harshest conditions—I mean, going through the brutal summers locked in those cells, and the coldest winters locked in those cells, and still have enough compassion to help save this city that have literally forgotten him. You know, I mean, a Common Ground never would have been sent out the way it was. It was started by a common—by an Angola Three supporter, scott crow. You know, it never would have happened without the Angola Three. And then this is the reward that he get for saving this city and this area, is to die in a prison cell. You know, I mean, it’s something that—you know, it leave a bitter taste in my mouth.

AMY GOODMAN: Malik and Jackie, I want to thank you for being with us. Malik Rahim, one of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party, knew Herman Wallace in jail and ended up running for Congress on the Green Party ticket. Jackie Sumell is building the house that Herman has dreamed of. Herman’s House describes their collaboration on PBS POV.

Media Options