Guests

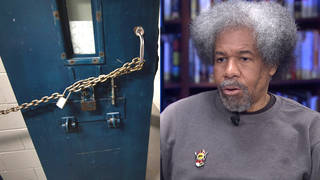

- Robert Kingmember of the Angola Three who spent 29 years in solitary confinement for a murder he did not commit. He was released in 2001 after his conviction was overturned. He’s written a book about his experience, From the Bottom of the Heap: The Autobiography of Black Panther Robert Hillary King. He is featured in a brand new film about his life called Hard Time.

- Carine Williamsattorney for Albert Woodfox with the law firm Squire Patton Boggs.

A federal appeals court has upheld a lower court ruling ordering Louisiana to release Albert Woodfox, a former Black Panther who has spent more than 40 years in solitary confinement — longer than any prisoner in the United States. Woodfox and the late Herman Wallace, another prisoner of the “Angola Three,” were convicted of murdering a guard at Angola Prison. The Angola Three and their supporters say they were framed for their political activism. A federal judge ruled last year that Woodfox should be set free on the basis of racial discrimination in his retrial. It was the third time Woodfox’s conviction has been overturned, but prosecutors have negated the victories with a series of appeals. Thursday’s ruling by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the order for Woodfox’s release in a unanimous decision. But prosecutors could still delay its enforcement with more appeals to keep Woodfox behind bars. We are joined by two guests: Robert King, a member of the Angola Three who spent 29 years in solitary confinement for a murder he did not commit; and Carine Williams, a lawyer for Albert Woodfox with the firm Squire Patton Boggs.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to new developments in a case Democracy Now! has been following for years. A federal appeals court has upheld a lower court ruling ordering Louisiana to release Albert Woodfox, a former Black Panther who has spent 42 years in solitary confinement—longer than any prisoner in the United States. In an editorial over the weekend, The New York Times referred to his confinement as, quote, “barbaric beyond measure.”

Woodfox and the late Herman Wallace, another prisoner of the Angola Three, were convicted of murdering a guard at Angola Prison. The Angola Three and their supporters say they were framed for their political activism. A federal judge ruled last year Albert Woodfox should be set free on the basis of racial discrimination in his retrial. It was the third time Woodfox’s conviction was overturned, but prosecutors have negated the victories with a series of appeals. Thursday’s ruling by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the order for Woodfox’s release in a unanimous decision. But prosecutors could still delay its enforcement with more appeals to keep Woodfox behind bars.

In 2010, the documentary In the Land of the Free featured a clip of Albert Woodfox speaking on a phone in prison.

ALBERT WOODFOX: If a cause is noble enough, you can carry the weight of the world on your shoulders. And I thought that my cause, then and now, was noble. So, therefore, they could never break me. They might bend me a little bit. They may cause me a lot of pain. They may even take my life. But they will never be able to break me.

AMY GOODMAN: Albert Woodfox, in his own words.

To talk more about these developments with the last incarcerated member of the Angola Three, we’re joined by two guests. In Austin, we’ll be joined by Robert King, a member of the Angola Three, who spent 29 years in solitary confinement for a murder he did not commit. He was released in 2001 after his conviction was overturned. We are also joined here in New York by Carine Williams, a lawyer for Albert Woodfox, an attorney with the firm Squire Patton Boggs.

We welcome you, Carine, to Democracy Now! I want to begin with you. You were with Albert when word came down from the court on Thursday?

CARINE WILLIAMS: I was. I already had an attorney-client visit planned, and the decision came down about three minutes before my flight landed. So, I tried to reach George Kendall, another attorney on the case, and confirm that in fact the ruling in the district court had been affirmed by the Fifth Circuit, and then stopped at a hotel lobby on the way out of Shreveport airport to print the case to bring to Albert and went as fast as I could to the prison, mindful of all the speed traps on the roads.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did Albert say?

CARINE WILLIAMS: You know, at first there weren’t a whole lot of words. As soon as I walked in, we both just broke out into huge smiles. This has been a long, long time coming. It’s something that we all expected, because the law was right on our side and the facts were right on our side, but it has been such a long road, that we just had to take a moment to savor it.

AMY GOODMAN: So, please, take us on that road. Explain how it is that Albert Woodfox has been in solitary confinement longer than any prisoner in the United States—42 years—though court after court says he should be freed.

CARINE WILLIAMS: There really is no explanation for it. I mean, it’s just a matter of retaliatory barbarism. And I think that—

AMY GOODMAN: How did he end up in jail?

CARINE WILLIAMS: So, Albert Woodfox originally went to prison on an armed robbery charge. He was then, while in prison, convicted of killing a corrections officer. During the investigation of that killing, he was put into solitary confinement. He never has been released from solitary confinement. There have been two intervening periods, where he—when he was retried in 1998, he was held in a parish facility for three years in the general population. At that point, no incidents whatsoever. Once the conviction was gotten for the second time—again, without a fair trial—he was put back into solitary confinement. In 2008, he was put into a dorm for about eight to nine months. When we got relief on his ineffective assistance counsel—of counsel claims, at that point, we sought bail. And in what we believe was a retaliatory move, they moved him out of the dorm and back into solitary for no legitimate penological reason.

AMY GOODMAN: And explain the case within the prison, when he was brought up on charges of murder, attempted murder of a guard.

AMY GOODMAN: So, in 1972, I think, for a little context, the conditions at Angola were atrocious. There was an inordinate amount of violence between—among inmates, among guards. Albert and Herman, Herman Wallace being the third member of the Angola Three, who passed away last year after having his conviction overturned, began organizing inmates as members of the Black Panther Party. And their primary goal in organizing inmates was to protect others from prison rape. And so, that earned them the ire of an administration that was itself under a big change. They had been ordered to integrate their prison administration, so there were some antagonisms and frictions among the prison officials and guards. And then, when this terrible murder happened—I mean, it’s truly a tragic crime—they were automatically, immediately fingered as the culprits, without any evidence whatsoever. And a number of people who were affiliated with that Black Panther chapter in the prison were put into solitary confinement.

AMY GOODMAN: Even the guard’s wife has said that they should be freed. Even when Herman was alive, she did not believe they were responsible for the guard’s death.

CARINE WILLIAMS: Right. That’s right, Amy. You know, anybody who looks—

AMY GOODMAN: Let me play Teenie Verret—

CARINE WILLIAMS: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: —the wife of the guard, the widow of the murdered prison guard. She was just 17 when her husband, Brent Miller, was stabbed to death in 1972. This is Teenie Verret from the documentary, In the Land of the Free.

TEENIE VERRET: I’ve been living this for 36 years. There’s not a year that goes by that I don’t have to relive this. And it just keeps going and going. And then these men, I mean, if they did not do this—and I believe that they didn’t—they have been living a nightmare for 36 years.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Teenie Verret, the wife of—the widow of the guard.

CARINE WILLIAMS: Right. I mean, this case, if you look at it, the state’s case has always been weak. It was weak in 1972 when the conviction originally happened. They could not get that conviction without cheating, without violating the constitutional safeguards of a fair trial. They had a second chance in 1998. Again, they couldn’t get a fair conviction against Mr. Woodfox, as the Fifth Circuit just found on Thursday.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined by Robert King in Austin, a member of the Angola Three who himself spent 29 years in solitary confinement for a murder he didn’t commit, released in 2001 after the conviction was overturned, has written a book about his experience called From the Bottom of the Heap: The Autobiography of Black Panther Robert Hillary King.

Robert, it’s great to have you back on Democracy Now! Can you respond to the court’s decision, yet again, on Thursday for Albert Woodfox to be released?

ROBERT KING: Yes. Thank you, Amy. It’s good to be here again. And, yes, I can only reiterate what Carine has said and alluded to, that Albert was overjoyed. I talked to him yesterday. And we’re thinking this, that this decision here gives—or puts him closer to his freedom. As, again, alluded to by Carine, you know, this case was weak from jump street, and it has been overturned many times, based not just on procedural defaults—I’m sure the court had other things in mind—but it was overturned on procedural default. And the attorney general seems to take this as a green light to continue this atrocious prosecution of Albert Woodfox. And we’re thinking this, that it is high time that the state let it go. There is nothing else that can be done. Albert has proven time and time again that he’s actually innocent of this crime. All evidence shows that he was innocent of this crime, that he should not have even been convicted, or should not have even been charged with this crime.

AMY GOODMAN: So, the question is: What happens now, Carine? So, the court ruled that—exactly what?

CARINE WILLIAMS: The court ruled that the conviction is a bad conviction and that he has to be released or retried. So the ball, in terms of what happens now, is, in effect, in the state’s court again. They have a few options. They can appeal, seek a rehearing of this panel. They can seek en banc review of the whole Fifth Circuit, or they can appeal to the Supreme Court. They could also decide that enough is enough, that Mr. Woodfox has served 42 hard years in Louisiana prison, and this is no longer a wise use of the state’s resources.

AMY GOODMAN: Robert King, we had you on talking about Herman Wallace, who prayed he could be free to die as a free man, and he was taken out of the prison at the last minute, as he lay dying, a judge ordering his release, demanding the warden release him or perhaps be imprisoned himself. And he was taken out in a gurney, and he died a free man. You and Albert Woodfox—Albert Woodfox in chains—were brought to say goodbye to Herman Wallace. Is that right?

ROBERT KING: Yes. In fact, we were allowed to visit Herman on the day, as Carine pointed out. She was there at the time, and she told him that his conviction had been overturned. And Albert and I were there, and we were also able to inform Herman and let Herman know that his case had been overturned, and that not only had his case been overturned, but that he would be released that same day from prison. And I think he recognized this. So, Herman did—he died unconvicted, a man free from murder.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to end with Albert Woodfox’s own words. He bent down in his chains and kissed Herman Wallace on the forehead as he said goodbye. But this is his own words from the 2010 documentary, the words of Albert Woodfox in The Land of the Free.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Our primary objective is that front gate. That is what we are struggling for, and we are actually fighting for our freedom. We are fighting for people to understand that we were framed.

OPERATOR: This call originates from a Louisiana correctional facility and may be recorded or monitored.

ALBERT WOODFOX: That we were framed for a murder that we are totally and completely and actually innocent of.

OPERATOR: You have 15 seconds left on this call.

ALBERT WOODFOX: Let me call you back.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Albert Woodfox, and that’s where we’re going to have to leave it until we speak to him live on Democracy Now! I want to thank Robert King, a member of the Angola Three. We will continue our conversation and post it online at democracynow.org. And Carine Williams, the lawyer for Albert Woodfox, an attorney with the firm Squire Patton Boggs.

Media Options