Six years after first promising to close Guantánamo, President Obama is beginning to free more men from the 13-year-old military prison in Cuba. Four Afghans were sent home this week, following six other Guantánamo prisoners sent to Uruguay earlier this month, four years after they were first approved for release. Their transfer was the largest for a single group out of Guantánamo since 2009. Meanwhile, Clifford Sloan, the Obama administration’s envoy for Guantánamo’s closure, has just submitted his resignation. But with 132 prisoners still behind bars, will Guantánamo ever close? We are joined by Pardiss Kebriaei, senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The United States has released four Afghan prisoners from Guantánamo Bay. The four men will all return to Afghanistan, where they’ll apparently be able to live without restriction. Earlier this month, six other Guantánamo prisoners were sent to Uruguay, four years after they were first approved for release. Their transfer was the largest for a single group of Guantánamo prisoners since 2009.

Meanwhile, the Obama administration’s envoy for the effort to close Guantánamo Bay has resigned—Clifford Sloan, a Washington lawyer. He headed the State Department’s Office of Guantánamo Closure for 18 months.

Speaking to CNN on Sunday, President Obama said he will do everything he can to close Guantánamo.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: I’m going to be doing everything I can to close it. It is—it is something that continues to inspire jihadists and extremists around the world, the fact that these folks are being held. It is contrary to our values. And it is wildly expensive. … We need to close that facility, and I’m going to do everything I can.

AMY GOODMAN: With the latest release, there are 132 prisoners left at Guantánamo.

To talk more about the significance of this, we’re now joined by Pardiss Kebriaei, senior staff attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: So there have been these series of two groups who have been released from Guantánamo. Talk about their significance.

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Right. So, all of these men were held for over a decade, for 12, 13 years, without charge. They were all approved for release by the Obama administration in 2009. The four men who went to Afghanistan had spent half of their imprisonment at Guantánamo waiting for release.

The significance, I think, is—you know, in terms of Uruguay in particular, it’s the first Latin American country, the first country in South America, to come forward and offer safe haven to men who need it in order to leave Guantánamo. President Mujica has really emphasized the fact that he’s doing this as a humanitarian gesture. He, himself, obviously, was a political prisoner for 14 years, was in isolation. So I think his expressions of support, the fact that Uruguay has come forward and taken six men—he released a letter from the State Department stating that the United States did not have enough information that these men were involved in conducting or facilitating terrorist activities. So I think this, for the region, is important.

And then I think we hope that there is more of an opening for more countries in South America and in the region to come forward and take the additional men who remain. There are 64 men, of the 132 still at Guantánamo, who have been approved for release, most of whom since 2009. So it is absolutely past time for these men to go home. We are now approaching the 13th year anniversary of Guantánamo. January 11th will be the beginning of the 14th year that these men have been in prison. So it is time—it’s past time to close it.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, in an interview, outgoing Uruguayan President José Mujica said he agreed to receive the six prisoners out of his long-standing opposition to Guantánamo Bay.

PRESIDENT JOSÉ MUJICA: [translated] That isn’t a prison. It’s a kidnapping den, because a prison entails subjection to some system of law, the presence of some sort of prosecutor, the decision of some judge—whomever that may be—and a minimal point of reference from a judicial point of view. Guantánamo has nothing.

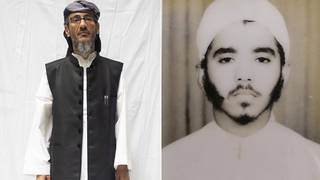

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: That was outgoing Uruguayan President Mujica. But earlier this month, Abd al Hadi described his new life. He’s one of the folks released there in Uruguay.

ABD AL HADI OMAR MAHMOUD FARAJ: [translated] Uruguay is a beautiful country. The Spanish class here is good, and I study two hours every day. I can speak a little Spanish, and I know how to say “Saturday, Sunday, Monday, Tuesday.”

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Pardiss, this whole issue of Sloan resigning, could you talk about that? And there’s been speculation that he was very unhappy with the pace of the releases, especially with the responses of the Defense Department to releasing the men in Guantánamo.

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Sure. And just on that point of the video you just showed, I mean, I think it is very important to note that the American public never has direct exposure to the men themselves. And I think that if we were to have that kind of exposure—and there are citizens of most of the world, of the rest of the world, that interact with former detainees, who can go to panel discussions and hear them talk about their imprisonment, who can have that exposure firsthand. We never get that here in the United States. And I think that really—that’s one of the reasons why I think these myths about who we have held and the fear mongering that continues to happen is allowed to continue. So, that’s just—you know, it’s important to note.

As far as Sloan, you know, I don’t know that we really have much insight into why he resigned. I think the point is that the administration needs to fill that position immediately. He’s played a critical role. That position has a critical role. It’s the special envoy, the person tasked with negotiating transfers. He was appointed by President Obama after the hunger strike, if you remember, in 2013, after a couple of years where that office had been closed. Since Sloan had been in his position, there have been nearly—there have been nearly two dozen transfers. So, the pace of transfers has been what we—what should be happening, what we expect to continue to be happening. And the administration absolutely needs to fill that position immediately.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to comments that President Obama made about Guantánamo while speaking to Candy Crowley on her last show on CNN over the weekend.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: There are a little less than 150 individuals left in this facility. We are going to continue to place those who have been cleared for release or transfer to host countries that are willing to take them. There’s going to be a certain irreducible number that are going to be really hard cases, because, you know, we know they’ve done something wrong, and they are still dangerous, but it’s difficult to mount the evidence in a traditional Article III court. And so, we’re going to have to wrestle with that. But we need to close that facility, and I’m going to do everything I can.

AMY GOODMAN: So, President Obama, one of his first acts in office as president, way back in 2009, was to close Guantánamo. Congress opposed it. What can he do? I mean, he’s done a lot on other issues right now, on the issue of immigration, for example. What can he do on Guantánamo?

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: He can continue this pace of transfers until all of the men, not just those who are cleared right now, but all of the men the administration does not intend to charge are released. He has the authority under Congress right now. There are countries coming forward to resettle men. There are a number of men—it’s important to be clear that this is now largely a prison for Yemeni detainees. Over 80 of the 132 who are still there are from Yemen. Some of those men want to go home. They should be able to go home. The administration has said that it’s going to review cases, individual cases, case by case. It should be looking at the specific circumstances of each of those people and determining whether some of them can go home. Some of them, frankly, want to go to third countries, and they should be resettled. And there are now countries coming forward to do that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But what can be done about that specific Yemeni situation, where obviously the government in Yemen, given the continuing strife there, is hardly in a position to say, “Well, we’re going to take all these guys back”?

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Well, I mean, I think there is—there is a certain number. Of the 64 who’ve been cleared, 55 are Yemeni. These are men the administration has determined do not pose the kind of threat that would require them to continue to be detained at Guantánamo. There is also this myth that all of the people at Guantánamo were ever engaging in terrorism to begin with. So the idea that they would—there’s a risk of returning to the battlefield is just—is false. So we need to be clear about that. There are administration officials themselves who said—the former commander—a former commander of Guantánamo said, easily, a third of the men there should not have been there, were mistakes. They later changed that to half of the men. So there is a history and a facts—you know, facts that we need to be clear about in terms of who we have held there.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, Pardiss, you know, it’s quite amazing, in the last few weeks, these historic developments, the U.S. and Cuba normalizing relations. For the U.S. to have this piece of land, what, rent it from Cuba, you would think since the U.S. has imposed this embargo for more than 50 years, what they’d want to do with that piece of land is show Cuba what they believe, what the U.S. government believes democracy should look like, should be conducted like. Instead, they have this prison there—

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: —where they’ve tortured and held men.

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: Many of them have been cleared for more than a decade.

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: Absolutely. And in the context of discussion right now about accountability for torture, I think it’s also important to note and be clear that when the U.S. releases people and sends them home, there is never a moment of acknowledgment of wrongdoing for having held them for 12, 13 years without charge and having tortured them. And we know that torture has happened, not just in CIA black sites, but in military prisons like Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: Should the U.S. give Guantánamo back to—this whole area, Guantánamo Bay, to Cuba?

PARDISS KEBRIAEI: I think it should. But a first step would be closing the prison—and closing it the right way, not whittling the number of prisoners down to some palatable number for the U.S. public and transferring them to prisons in the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: Pardiss Kebriaei, I want to thank you for being with us, senior staff attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights. When we come back, an unhappy Christmas story. A woman who gets in a cab in a small island nation called East Timor ends up in prison. We’ll find out why. And then a remarkable Christmas story, as a prisoner returning to Cuba sees his wife for the first time, gets to hold her for the first time, in years. She’s about to give birth to a baby in about two weeks. Stay with us.

Media Options