Related

Guests

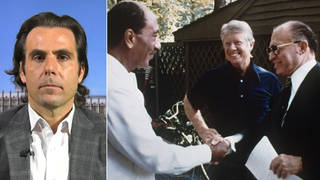

- Justin Simienwriter-director of Dear White People, which won the U.S. Dramatic Special Jury Award for Breakthrough Talent at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival and is set for release later this year.

- Marque Richardsonactor in the film Dear White People. He also appeared in the HBO series True Blood.

As colleges across the country, from Harvard to University of Mississippi, continue to witness racism on campus, we look at a new film that tackles the issue through comedy and satire. “Dear White People” follows a group of black students at a fictional, predominantly white, Ivy League school. One of the main characters, Sam, hosts the campus radio show “Dear White People,” where she confronts the racist stereotypes and dilemmas faced by students of color. Racial tensions on campus come to a head when a group of mostly white students throw an African-American-themed party, wearing blackface and using watermelons and fake guns as props. We speak to actor Marque Richardson and award-winning, first-time director Justin Simien.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: A new film tackling racial politics in contemporary America is getting a major Hollywood break. The film, Dear White People, took the Sundance Film Festival by storm earlier this year, winning U.S. Dramatic Special Jury Award for Breakthrough Talent. Now, Lionsgate and Roadside Attractions have acquired rights to the film, pretty much guaranteeing a wide U.S. and Canadian distribution.

Dear White People examines race relations through comedy and satire. While it elicits many laughs from the audience, at its core, it’s a serious film. The film follows a group of black students at a fictional, predominantly white, Ivy League school called Winchester University. One of the main characters, Sam, hosts a radio show on campus called Dear White People, where she confronts the racist stereotypes and dilemmas faced by students of color. Racial tensions on campus come to a head when a group of mostly white students throw an African-American-themed party wearing blackface and using watermelons and fake guns as props.

The concept is not all that far-fetched. Just as the film was premiering at Sundance, a fraternity at Arizona State University decided to mark Martin Luther King Day by holding a, quote, ”MLK Black Party” where white partygoers donned basketball jerseys, flashed gang signs and drank from cups made of watermelons. When posting photos of the event to social media, they used hashtags like “hood,” “blackout for MLK,” “my boy martin” and “kill em.”

More recently, three freshmen were expelled from their fraternity at University of Mississippi, popularly known as Ole Miss, for hanging a noose and plastering a flag bearing the Confederate symbol on a statue of James Meredith, a civil rights hero who was the first African American to attend the university. The fraternity was also suspended after the incident, which took place in February during Black History Month.

Further north, at one of the world’s top universities, students of color say they’re tired of people suggesting they don’t belong. Black students at Harvard recently began a photo montage campaign called “I, Too, Am Harvard” that went viral. In it, students hold signs that say things like “Having an opinion does not make me an 'Angry Black Woman'” and “No, I will not teach you how to twerk.” A Harvard student named Ahsante Bean made this promo video for the campaign.

HARVARD STUDENT 1: There’s always that moment when you’re the only black student in your section.

HARVARD STUDENT 2: When, in class, and you’re the only black kid, and this—the N-word comes up or some—in a book or something where there’s slavery or whatever it is.

HARVARD STUDENT 1: And the issue of race comes up or the issue of slavery or the issue of whatever. Everyone looks to you …

HARVARD STUDENT 2: Everyone looks to you —

HARVARD STUDENT 1: … as if you’re about to speak for your race.

HARVARD STUDENT 2: As if, like, you represent everybody in the race, and suddenly your voice will, like, carry such weight.

HARVARD STUDENT 1: And it’s kind of frustrating, because you would hope that people would understand that there are all different types of black people, and black people don’t all have the same opinions about the same issues.

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt from the promo video, “I, Too, Am Harvard.”

Well, black students have launched similar campaigns across the country, including at the University of Mississippi, after the incident involving the James Meredith statue, and at University of Michigan, after a fraternity planned a “hood”-themed party invoking racial stereotypes. That party was canceled following an uproar. Campaigns by students of color demanding acceptance and respect have also been launched abroad, at Cambridge and Oxford.

Well, the film Dear White People deals with these very real issues in creative and often humorous ways. The film just showed here—is showing this weekend at New Directors/New Films festival presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art. It’s scheduled for a theatrical release this year.

While at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, earlier this year, I sat down with the film’s director, Justin Simien, who was recently named one of Variety's “10 Directors to Watch.” We were also joined by Marque Richardson, who plays Reggie in the film. I began by asking the director, Justin Simien, about the film's storyline.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: You know, the story revolves around four black kids at a mostly white Ivy League college. And Samantha White is—you know, she’s sort of this Angela Davis, Malcolm X, Huey from The Boondocks, you know, Lisa Bonet’s character from The Cosby Show amalgamation of, you know, a girl who really hangs her identity on being this black militant in this white place and sort of really challenging the status quo and trying to, what she calls, pop the post-racial bubble and sort of this illusion that because Barack Obama is president and, you know, everyone loves Beyoncé, that somehow we’re all past race. You know, that’s really her thing.

Lionel Higgins, who is sort of like on the polar opposite end, has no black identity to speak of in the beginning of the film, and because he is also gay and dealing with sexual issue—you know, sexual identity issues, is sort of really feeling sort of, you know, like he belongs in no place and very much in the middle and sort of watching the other black characters in the film from the sidelines.

Coco Conners, whose government name is Colandrea, is, you know, also kind of a flipside of Sam. She’s just taking a different approach to sort of owning her black identity. You know, some might call her a bit of a conformist. She definitely comes in the package that I think, you know, the people at this particular school would, you know, expect—what she believes that they expect from. But she also is kind of daring and cunning in her way of surviving in this place.

And then you have Troy Fairbanks, which is—he’s sort of the poster black child of diversity of the school. He’s the son of the dean. He’s a legacy kid. He’s a, you know, perfectly coiffed sort of, you know, Essence, Ebony magazine kind of black man and is sort of like a nonthreatening version of black for his white friends, but, you know, he can black it up when need be for his black friends. So—

AMY GOODMAN: And his dad is Dennis Haysbert, who is—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: His dad is played fantastically by Dennis Haysbert, who—

AMY GOODMAN: Who is the president of the United States in 24.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s right. That’s right. That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: In 24.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s right. But, you know, at Winchester, only the dean. There’s also a president of the school, that doesn’t deserve it, but is, you know, his boss. And it’s that sort of like—you know, when a—

AMY GOODMAN: Who is white, and the dean is black.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, exactly, who is white. And I just wanted to sort of get into the pressure that I, as a black man, feel from, you know, my parents’ generation of just sort of what they had to go through and, you know, this idea that the “Talented Tenth” has to work 10 times harder, and we have to appear perfect and, you know, have everything. That’s a kind of pressure that I don’t know if people who aren’t minorities feel.

AMY GOODMAN: So, who are you?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Who am I?

AMY GOODMAN: In Dear White People.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Oh, god, I’m all of them. I’m all of them, truly. I mean, I like to say, because it’s easy to say, that I entered college Lionel and left as Sam. But the truth is, is that I’m each one of those characters. I mean, there are really autobiographical threads in all of them.

AMY GOODMAN: So, it’s amazingly diverse. And here at Sundance, when the film premiered, one of the audience members raised their hand and congratulated you for the diversity. And in response, you came out.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, yeah, that’s true. I mean, I’ve never been in, but yeah. I mean, that happened years ago. But, you know, no one has really asked me to stand in front of a bunch of people and talk about myself, so, you know. But yeah, I mean, I think it’s an—I think it’s an important thing to talk about. I think it’s a thing that, like, is still an issue in the black community for black men to own their sexual identity and to say that, yeah, I can be all of these things and be gay and be black, and still it’s all good. All these things can still—can coexist together. And, you know, I think Lionel’s trepidation over that is certainly an anchor for a lot of people in the film.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Justin, talk about the inspiration for this film.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: The beginning really came from two places. I mean, I had had a college experience that was certainly not as extreme as the events that take place in the film, but, you know, this sense of being one of very few black people in the room and having to sort of toggle my blackness and what parts of my identity I showed to people based on what groups of friends I was with was something that I felt like that was kind of what all of my friends were doing and feeling the pressure to do, and I wanted to talk about that in the movie. And—

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you go to school?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I went to school at Chapman University. It’s a great school.

AMY GOODMAN: In California.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, a great school, really lovely people, lots of people touching my hair, lots of people thinking I could play basketball. You know, it was funny. It was like—it was kind of anecdotal. And that’s really where it began. And it really wasn’t until I started to research particularly what has happened at Ivy League schools, research blackface parties, which are unfortunately a very common occurrence in predominantly white institutions, that the script really, for me, began to be more about the American black experience, as opposed to my specific college experience. And I began to treat Winchester University as a microcosm of, you know, this sort of identity crisis that I feel like—I know I’m having, that my black friends are having, and, you know, just—and finding ways to sort of broach these sort of uncomfortable topics, you know, as we go through life.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, you’ve been driven to do this. It’s not like it’s your 10th film.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: This is your first film.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: And you’ve been working on it for a few years. What were you doing in between?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I actually was a studio publicist for a while. I worked at several major studios doing publicity, online publicity, that kind of thing, and most recently was doing sort of like independent—I’m sorry, not independent, but doing Internet content, like digital content, and all along, on the side, sort of writing and trying to work on the craft and push the boulder up the hill for the movie.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, what made you finally put down the day job—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —and just do the other full-time?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I think what it was is we made a concept trailer, you know? I had a script that I believed in. And particularly with a multi-protagonist script about—you know, ruminating on black consciousness and identity, you know, I felt like I needed to do something to give people a reason to let it come in the room and pitch myself. So I, you know, poured my tax return into a concept trailer.

AMY GOODMAN: And a concept trailer, for people who don’t know, is just sort of like a—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: It’s like an as if—

AMY GOODMAN: —big trailer?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: As if the movie existed. You know, we cut like a three-minute piece, and I just shot what’s in the trailer. You know, we shot it very quickly over two days, with no money, and put that online, and it blew up. And, you know, a year and a half later, we were able to get the financing and actually make the movie. So, when the concept trailer hit, though, I just felt like I needed to do something dramatic. And so I quit my job and basically said, “You know what? Making this movie is the only thing that matters to me right now.” And it was a year and a half of figuring out, but we finally did.

AMY GOODMAN: The director of Dear White People, Justin Simien, speaks to us at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah, earlier this year. In our next segment, he’ll be joined by Marque Richardson, who plays the character Reggie in the film. We’ll have more in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we go back to our interview with Justin Simien, the director of the remarkable new film, Dear White People, that just played in New York this weekend. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year. With him is Marque Richardson, who plays the character Reggie in the film. I asked Justin Simien about his ensemble film, Dear White People, and who inspired him as he was making this film, his first ever.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I’m a big fan of ensemble films. They’re probably—it’s probably my favorite genre. I just love the way they’re put together, and particularly when it comes to issues. I love films that talk about things like race from many, many different, conflicting points of view, because it’s not—I never wanted to make a morality play. I never wanted to say this is how it is and this is what you should feel. I wanted these characters to disagree with each other and to all be struggling to figure out the answer, because, you know, I just think that that’s more interesting. I think that speaks to the human experience. Movies like Network do that. Movies like Do the Right Thing do that, Election, even The Royal Tenenbaums. Like, they find a way to talk about the human condition from all of these different points of views. And particularly with race identity, I couldn’t—I can’t think of another way to do it. You know, there’s just so many different ways to go about it.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Reggie—well, you’re Reggie in the film; you’re Marque Richardson in real life.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yes, ma’am.

AMY GOODMAN: But talk about your character, Reggie.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah. Reggie represents the angry black man in my head. And so, in doing a lot of research, you know, for the project and for Reggie, I was listening to a lot of Malcolm X, Public Enemy, Flavor Flav, you know, just all of these prominent black leaders, and James Brown, you know, and—in terms of, you know, rebelling against the man or really having that strong black identity, and that’s it. You know, so.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about who Reggie is in—at Winchester University, where you go to school.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Reggie is—I had it that he’s the Michelle Obama to Samantha, who is the Obama. You know, he’s her support system, that’s—he does everything for her.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, Sam is Dear White People. She has a radio show. She has a voice, and she is angry.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yes, yeah. Yeah, she is. And she’s amazing. I’m going back into my character right now, [inaudible] character.

AMY GOODMAN: That you worship her.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah, I worship her, pretty much. Yeah, pretty much. So—

AMY GOODMAN: And you’re an IT guy, too—I mean, in the film. You’re very good. You know how to work the system. You—

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yes. Yes, yes, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And that serves you very well. What was it like to perform in this ensemble company? And how do things change? I want to ask both of you this. When you’re all together, do things change as you’re—you know, your lines change, the feelings change, as you’re working together? Do you get inspired by the other people on the set?

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah, I say I was inspired by everybody on the set, just in terms of—because a lot of these people were my friends before we actually started to work. And, you know, to be able to work with your friends and actually work on a project that you’re so proud of, even though it’s not the easiest thing to do, was phenomenal. It was like a summer camp. And, you know, you take—I just took everything that happened and used it in the work, and you stay present. And, you know, we created this. So—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: And Marque Richardson is a beast, man. I mean, what was cool about it is that, like, it was just a bunch of beasts. I mean, seriously, like these really incredible actors who had not had a chance to really show this side of themselves in a movie before. And it was great to just see them sort of like see each other other’s takes and get inspired. And, you know, you talk about things changing. I mean, you know, they always say there’s a movie that you write, there’s a movie that you make, and then there’s a movie that you edit, and they’re all different. And, you know, we had a very tight budget and schedule, and so, yeah, stuff changed all the time. I mean, there were all sorts of days where you’d walk in and say, “Oh, well, this is the set we’re shooting on now. How do we make the scene work for that?”

AMY GOODMAN: So let’s go to the first clip. This is in Dear White People where Samantha White, who is played by Tessa Thompson, confronts Kurt Fletcher. Kurt is the character in the movie, and he’s the son of the university president, President Fletcher. He’s in the dining hall of Armstrong/Parker House. And explain Armstrong/Parker House.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Armstrong/Parker House is sort of the residence hall that’s deemed like the black house, like where the black kids that want to be around other black kids historically have gone to. And it’s basically being challenged by the administration, who thinks it’s a sort of self-segregation, and so they’re actually—they’re actually randomizing housing. And so, this sort of like, you know, history of black students going to this school is in danger for the first time.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to the clip. And then I want to ask Marque what was it like to shoot this scene. This is Dear White People.

SAMANTHA WHITE: [played by Tessa Thompson] Well, on behalf of all the colored folks in the room, let me apologize to all the better-qualified white students whose place we’re taking up.

KURT FLETCHER: [played by Kyle Gallner] No, it’s fine. We’re OK.

SAMANTHA WHITE: I’m sorry. Did you get lost? Bechet [phon.] is that way.

KURT FLETCHER: I know where it is. I’m actually supposed eat there. Yeah, it’s just there’s—this is the only dining hall that you can actually get yourself some chicken—and waffles. Look, you’re Dear White People, right? It’s funny. It’s funny stuff. It really is. How have we not staffed you yet?

SAMANTHA WHITE: Oh, me? Oh, what? On Pastiche, your uninspired humor magazine?

KURT FLETCHER: It’s actually much more than just a magazine, sweetheart. SNL’s staff is basically half-Lampoon, half-Pastiche. Same goes for the network comedies.

SAMANTHA WHITE: And what gives you clubhouse kids the right to come to our dining hall? You don’t live here.

UNIDENTIFIED: Sam, what are you doing?

SAMANTHA WHITE: So you can’t eat here.

TROY FAIRBANKS: [played by Brandon Bell] Chill, Sam. Damn, all right, let the man eat.

SAMANTHA WHITE: Got this.

KURT FLETCHER: Got this. Look, who are you to throw me out?

SAMANTHA WHITE: Well, I think I’m head of this house. And I’m doing things my way.

AMY GOODMAN: That last voice, Sam White. She is the radio announcer, the radio host, and now the president of Armstrong/Parker House, throwing out the white guys. Yes, that’s a clip from Dear White People. And our guests in studio are here at Sundance Film Festival headquarters, are the star of—one of the stars of this ensemble production, Dear White People, Marque Richardson, as well as the director, first-time director Justin Simien. Marque, talk about that scene.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: That scene was just—to be there and to watch the work—first off, the work of Tessa and Kyle, like Justin said, they were just beasts, and to see them play and to see them go at it with each other was just phenomenal, to be a witness of it. And then, for my character, anyway, it riled me up.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: OK.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: It was arousing, you know, because—you know, Sam is Reggie’s muse. I mean, he does everything for her. And just to sit there and watch her work, as Reggie, was just—you know, that was love.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I think, in a lot of ways, too, Sam is sort of like—Sam and, then, eventually, other characters are sort of like mouthpieces for Reggie. Like—

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I think he—I think he likes when she does things that maybe he’s too timid to do, you know, which I think is an interesting—

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I mean, I love—you know, one of the things I tell the actors is, in the cutting room, like I love to watch—you know, because the camera is on lots—on all the different groups in Armstrong/Parker House in that scene, and I love to watch them when they’re not on camera. You know what I mean? When I know we’re going to cut to Sam and Kyle, but I love just watching—I just loved watching them watch what was happening, because they never turn off. They’re just always in the moment, and all these—so many good reactions to choose from.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Marque, in your life, how much do you identify with Dear White People?

MARQUE RICHARDSON: A lot.

AMY GOODMAN: Where did you—where were you born?

MARQUE RICHARDSON: I actually—I was born in San Diego, and I went to USC. And right before—

AMY GOODMAN: University of Southern California.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah, University of Southern California—fight on. But right before this interview, I told Justin, I said, “I just realized that I actually lived on an all-black floor at USC.” And it just hit me that I lived this. You know, I lived this. And, you know, we would go off campus and integrate with other students and whatnot, but, you know, they would ask us why. You know, “Why are you integrating yourselves? Why are you—you know, just living in your own world?” And it was a support system, you know, to go out there in the world and have people try and touch your hair, have people, you know, professors, say these things to you, and to go back home and to share that experience with your people.

AMY GOODMAN: Interestingly, Sam, Tessa Thompson, throws out not only Kurt, the white president’s son—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —who ends up throwing the—what would you call it? Not “block party,” “black party,” whatever you call it.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: The costume party. But she also throws out Lionel.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Mm-hmm, yeah. I wanted to—first of all, I wanted to—I’m always about telling the truth and being honest, and I didn’t want—I didn’t want these to be just grandstanding archetypes. I wanted them to be complicated and complex and to sometimes do things that confuse people.

And one of the things that I experienced in college—I’ll never forget it—is, there was a moment when I was sitting in—you know, and I was new to the school, and, you know, I don’t think particularly at the time I came in the expected, you know, black male package. I was kind of a mess. My hair was all over the place, not quite where Lionel’s is in the movie, but—I don’t know. I don’t know what it was about me, but, you know, the Black Student Union meeting started to happen around me in this area that I—you know, I had seated to study and was kind of waiting for the meeting to start. It would have been my first meeting. I was brand new to the campus. And there was something about me they just didn’t think I was down enough. And they were just like, “Hey, so you know we’re doing Black Student Union here. You might want to like leave.” And I just remember, like, ooh, like that was such an awful feeling to not feel black enough in that environment, when, like, I feel like exoticized for being black in other—you know, in other areas of my experience.

And, you know—and also because Sam White, in that moment, is saying, “If you don’t live in this residence hall, you don’t eat here,” it wasn’t—I didn’t want to make it specifically about the fact that they were white, because then that would make her just a racist. And, to me, that’s not interesting. What’s more interesting is her being about the principle of it, like if you’re not down enough to live in Armstrong/Parker, you don’t get to eat here. And that, to me, was more interesting.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, you have Lionel, the black, gay character in this film, being thrown out here.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: But when he walks into the newspaper room, he’s assuring the white student, “I’m not going to write for you. Don’t worry.”

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And I wanted to talk about that toggle, that weird toggle of like—it’s like a tap dance, you know what I mean? It’s like it’s a softshoe. You’ve got to—you’ve got to sort of be—you don’t have to be, but certainly in college I felt a pressure to be different things to different groups of people, because of—you know, when you walk through the world as any minority, when you walk through the world as a woman, like, in every space you go, there’s—you’re aware that you are what you are and that people are going to have, you know, ideas about you just by seeing you. And I wanted each of the characters to be dealing with that conflict of their identity versus who they really are.

AMY GOODMAN: Dean Fairbanks, the African-American dean, says to Sam that she’s racist, and Sam replies, “Black people can’t be racist.”

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, yeah. Actually, you know what? I don’t believe—I don’t agree with everything Sam says. I just want to put that for the record, like Sam is not my mouthpiece. Neither is Lionel. None of the characters just say what I believe. But I actually agree with her. I think racism is—it speaks to a system of disadvantage. I think that like, certainly, there are people who can be called racist because of very specific attitudes that they have, but it’s about coming up in a system and being at a disadvantage because of race. And I think when you look at racism as a system, you know, as an infrastructure, I think that that is—that’s more truthful, because people can be polite to me all day long and be sweet and nice, and I’ve never—I personally have never run into a lynch mob or had any issues like that, but I am at a disadvantage as a black man in this country, and that it’s a much more complicated issue than just like what are you—being PC or being polite or, you know, saying the right—what’s expected of you in a situation.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to another clip.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: And this is Sam and Dean Fairbanks. Justin, set it up for us.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Oh, sure. So, this is—Dean Fairbanks is concerned that Sam’s sort of like movement on the campus is gathering a lot of negative attention for the university, so he confronts her over a would-be rally to save the “blackness” of Armstrong/Parker residence hall.

SAMANTHA WHITE: The role of counterculture is to wake up the mainstream.

DEAN FAIRBANKS: [played by Dennis Haysbert] I have furniture older than you. Counterculture? Is that what you think this is? Your little show?

SAMANTHA WHITE: What about my show?

DEAN FAIRBANKS: Your show is racist.

SAMANTHA WHITE: Black people can’t be racist. Prejudiced, yes, but not racist. Racism describes a system of disadvantage based on race. Black people can’t be racist since we don’t stand to benefit from such a system.

DEAN FAIRBANKS: Your antics are making press, Sam. And press like this keeps men like President Fletcher up at night.

SAMANTHA WHITE: Warm milk?

DEAN FAIRBANKS: He’s building a file on you.

SAMANTHA WHITE: OK, it’s not my fault that your son couldn’t beat me in an election.

DEAN FAIRBANKS: I’m sure it was tough growing up, wondering which side you’d fit into, feeling like you have to overcompensate, perhaps.

SAMANTHA WHITE: If that’s true, Dean, I’m not the only one.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from Dear White People, that’s premiered here at the Sundance Film Festival. Justin, talk about that.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: You know, with that scene, I just—I really wanted to make a point of these two very different, but kind of valid in their own way, approaches of surviving in this place. I think, you know, for Dean Fairbanks, who kind of represents maybe an older guard, a different generation’s way of thinking, you know, the answer is to not shake the boat, to simply be excellent, be better than excellent, and to never be controversial. And for Sam, you know, her thing is to just break everything in sight and cause a fuss. And I think that they both have really valid points, actually. And I think that they’re both right in the scene. And I love—I love movies that do that, and I love scenes that do that, where you have two people that do not agree with each other, and they’re both right, and they’re both wrong. And I just wanted to—you know, I just wanted the two of them to come head to head in that way.

AMY GOODMAN: We haven’t even talked about what this whole film leads up to, and that is the—what, the African-American-themed costume party. Was this Halloween?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, Halloween in the film, yeah, mm-hmm. But, you know, there’s a billion—I mean, they happen at—it happens at Halloween time, happens for Martin Luther King Day. You know, it happens a lot. And sometimes—and oftentimes it doesn’t even make the news. I mean, a lot of times, you know, in just doing research and talking to people, they’re like, “Yeah, that happened at my school. It never got out, but it happened.” And it’s happened at Ivy Leagues. It’s happened at smaller institutions. It happens, you know, in grad programs. Like, it’s a thing that happens.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, as we just said, it just happened at Arizona State University—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, just happened. Yeah, that’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: —for Martin Luther King Day.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s right. That’s right. And I think—you know, I think part of it is—and what I also wanted to do, I didn’t want to vilify anyone in the film. I think that one of the most interesting things about researching these parties is the responses that these students give after the fact. And believe it or not, there really is a sort of a naïveté to what they’re saying and a really sort of like—they kind of didn’t realize like how messed up this was and didn’t completely comprehend how that would come across to a minority, particularly in those environments. And ultimately, the movie, to me, is not even really about racism; it’s about identity and about sort of like what is the mask that you wear, what is the mask that you’re forced to wear by the culture around you. And there’s no better way to get into that than by showing students who are literally wearing blackface and wearing these masks and wearing these costumes that, to them, represent Martin Luther King. To me, like there’s just no—there’s no—that, to me, was like a perfect end, and particularly since it’s kind of a phenomenon. I mean, it happens every year, all the time, no matter how many times these controversial stories come out.

AMY GOODMAN: And you show clips—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —from around the country.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, not just below the Mason-Dixon Line.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s right, yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You have Dartmouth. A fraternity-sorority holds a “Bloods and Crips” party. We have—just saw Arizona State, Florida. How did you do the research? How did you find all this?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I mean, Google is a really easy way to do it, but also asking a lot of questions and reading a lot. You know, there’s a lot of books that went into just, you know, my understanding of the issue. I wanted to—I wanted to tell the truth, but I also wanted to be fair, and I wanted to be honest. And I didn’t want anyone to come across as a villain, you know, so—so, yeah, there was a lot of that. And I specifically looked for the response from, you know, the fraternity or the group or whoever did it. I was looking for the response that they gave. And also a big influence was just what happens on TV, like, you know, when you have these sort of mostly white comedy rooms that do black jokes. You know, whether it’s, you know, cartoons for adults or sketch shows or whatever, like, you find these sort of black jokes bubbling up from all-white writers’ rooms, and it’s interesting. And I can always sort of tell that there’s—when there’s not a black guy in that writers’ room and—or a black woman, for that matter. And I just thought that that was interesting, because I think, for some people, because racism is—it’s more subversive now, and it is about the infrastructure, as opposed to, you know, specific, say, rights being taken away—of course, that’s an issue, too. Particularly in this past election, we saw that. But, you know, because it’s sort of relaxed little bit, I think people feel the right and, you know, feel like it’s OK to sort of—to make those jokes, but they don’t realize that it actually—it really is harmful and hurts, you know, for a minority to see that kind of stuff.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have the characters at this party literally unmask.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. And they all have—they all arrive at the party with different ideas about it.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have a leading African-American character, black woman, Coco.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain her role in all of this.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: To me, Coco is the kind of person that understands that identity is just a form of currency. Like, I don’t think that she—I think that she actually, in a funny way, knows more who she is than Sam does at certain points. And she just—she realized that being a black person, it’s not—it’s a mask that I wear anyway, so why not use it to get what I want? And, you know, she—I don’t want to give too much away, but she is involved in the party, in ways that may feel a little unseemly, but honestly, we all do it. We all do it a little bit. And, you know, we all sort of use our blackness to get us someplace. That’s been my experience. And I don’t know if everyone wants to cop to that or admit to that, but sometimes it comes in handy. And the way people see you, you know, is something to be used sometimes.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s the director of a new film called Dear White People. He is Justin Simien, speaking to us at Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, along with Marque Richardson, who plays the character Reggie in the film. Richardson has played a number of roles, including Kenneth in the HBO series True Blood. We’ll have more with them in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: We go back to our interview with Justin Simien, the director of the remarkable new film Dear White People, which premiered at Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, where the film won a U.S. Dramatic Special Jury Award for Breakthrough Talent. Dear White People also played in New York this weekend at the New Directors/New Films cinema—festival, with Justin Simien and Marque Richardson, who plays the character Reggie in the film. I asked Justin about the theme of reality shows that runs throughout Dear White People.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: You see this with every—especially now, every ethnic pocket. Every cultural pocket that seems a bit different from the mainstream now has a reality show around it. And you have these people who I think probably feel a pressure to really play up whatever their thing is, because without that, the show is really not that interesting, you know, if they’re not the extreme version of whatever it is the thing is, you know, whether it’s a show set in Atlanta or Jersey or whatever the—whatever the subculture may be. I mean, you know, it’s entertainment. They’re sort of using their identities to entertain the mainstream culture. And there’s something about that that’s very disturbing. And I wanted—but there’s also—there’s also opportunity there for these people to make a living and to make a life for themselves, and I kind of wanted to—I wanted to get into that a little bit, because that’s a reality of being a minority in this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Marque, did you ever experience anything like this on campus, a black-themed party, not African-American partygoers, but the whites on campus?

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah, it was—it wasn’t a black-themed party, but, I mean, you have, you know, Cinco de Mayo parties. You have, you know, Chinese New Year.

AMY GOODMAN: Cinco de Mayo parties.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah, all these different—so, as minorities as a whole—right before we started shooting, a friend was throwing a white-trash party. That’s what they called it, a white-trash party. And I had read the script. And prior to reading the script, I probably would have went. I probably wouldn’t have even thought—you know, I wouldn’t have thought anything of it. But I didn’t go, because it was the same thing—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: —in terms of—you know, whether it’s economics, it’s the same thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Marque, you’ve acted in a lot of different productions, like True Blood, for people who know that vampire series.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah, some [inaudible].

AMY GOODMAN: What about your experience in getting jobs, the few jobs for African Americans? This is an amazing film, because you actually see, you know, a core of African-American actors, characters. How much—how different is this from your other work?

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Well, first off, we—you know, Justin allowed us to play, you know, and this was—I honestly can say that this is the proudest thing I’ve ever worked on. So, you know, just from the work, just from the message, just from all that it is, so that’s the hugest difference for me. In terms—I think, in terms of black actors, you know, we are put into a box. I, fortunately, have not been put into a box. A lot of the stuff that I’ve done has not been, you know, the stereotypical gangster, or I haven’t had to wear a dress—but not saying I’m not opposed to it, but I have not had to do it.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Not on camera, anyway.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Not on camera, anyway. Just for the wrap party. But I have not had to do that. So, to actually play this militant character was exciting for me, because I don’t live there, you know? I don’t—in my life, I don’t live there. I do get angry a lot about different things, but I don’t live there.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s talk about the rule book that Sam White writes, “Ebony and Ivy.” It’s interesting, because we just did an interview with Craig Wilder, and he wrote the book, Ebony and Ivy—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —which is about the roots of Ivy League universities, how they gained from slavery, actual slavery, in their founding. But she has this rule book she has written. Talk about it.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure. It’s a survival guide. It’s a survival guide for being a black face in a white space. And, you know, I thought—it’s just something that I thought she would do. And in it is a series of, what they’re called, paper bag tests. And it’s meant to be tests for black people to take to find out how black they are. And she’s—you know, it’s just sort of her tongue-in-cheek, you know, kind of anarchistic way of getting her point across, that it really does take sort of wearing a certain mask to survive at this place.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s go to another clip from Dear White People, and this is Samantha White narrating, well, one of those tests.

SAMANTHA WHITE: The tip test. You hit up Jellies for a snack. Your waitress mistakes you for someone who looks like you, black, who once ran up a $30 bill and left a dollar tip. You watch all the other customers order before you do.

LIONEL HIGGINS: [played by Tyler James Williams] Pastrami sandwich on rye.

SAMANTHA WHITE: And then proceed to wait no less than 40 minutes for your food. How do you tip? A.

LIONEL HIGGINS: Forty minutes? She’s lucky if she gets 40 cents. OK, you do a good job, maybe see a tip.

SAMANTHA WHITE: B.

LIONEL HIGGINS: She was trippin’, but 15 percent is the least I can do.

SAMANTHA WHITE: Or C.

LIONEL HIGGINS: I reject the stereotype that African Americans do not tip. I will leave 20—no, 25, just to prove that I can.

“One Hundred, Oofta, Nose Job”?

AMY GOODMAN: So that ended with—well, that was the narration of Sam and ends with Lionel saying he’s going to tip big.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Justin?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s—I mean, I’m sorry, but that is a real pressure that I feel as a black person whenever I go to a restaurant.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Same, same, same, yeah.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Especially when the service is bad, because like—it’s like, well, damn, like, I don’t want to—I don’t want to reinforce the stereotype, but I also—like, you didn’t come and check on us for like an hour, you know? And I’m, unfortunately—you know, I fall—I pick C just about every time. You know, I always overtip, because I feel this pressure that I’m expected to undertip. And it’s a thing, like it’s a real thing that I just think is an interesting aspect of being a black person in the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Marque, you raised your hand.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Same, guilty, guilty of it. But—but I refuse—you know, if I get bad service, I’ll leave a reason. I’ll write a reason on the receipt—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: —why you’re not getting a tip, so it was not because I’m black. It’s because you didn’t check on me for 20 minutes. Yeah.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s a better way to do it.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Yeah.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s a better way to do it.

AMY GOODMAN: What are some of the other rules?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Well, there’s a couple things that didn’t make the film that, you know, we’ll see what happens in the future life of these characters. But there was a dance test that was in there for a long time. It was called the twerk test, of what do you do—what do you do when there’s like a dance craze that’s sweeping the nation that starts with black people, whether it’s the “Single Ladies” dance or how to Dougie or the twerk.

AMY GOODMAN: Wait, the “Single Ladies” dance?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, remember the Beyoncé “Single Ladies” dance? How to Dougie or twerk, whatever it may be, and all your white friends are expecting you to teach them how to do it, which is also a really annoying, but very real aspect of being a black person with a bunch of white friends, because, one, like even if you do know how to do it, there’s just something that feels wrong in like sort of like getting up and teaching people how to—I don’t know, it just feels weird, feels a little too close to like tap dancing.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: Shuckish—

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

MARQUE RICHARDSON: —and jivish, you know?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, feels a little—it’s slightly shuckish. And so—

AMY GOODMAN: But you took it out.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah. Well, you know, we couldn’t—we couldn’t shoot it, unfortunately, just time and budgetary restrictions. But it is, you know, one of the realities of, you know, what do you do in that moment? Do you just teach them? Do you act like you don’t know it? Or, you know, do you like throw a big fit and “How dare you? And, you know, I will never shuck and jive for you, you know.” But, you know, it’s—I don’t know. I just thought those were funny ways to talk about, you know, the kind of awkward moments that kind of happen for people who sort of live in between all the cultures like that.

AMY GOODMAN: So, one other thing, here you’re on Democracy Now!, a global news hour, and of your main characters, two of them are journalists, in a sense. I mean, you’ve got Sam with her camera all the time.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: And she’s got that microphone in front of her face saying, “Dear White People.”

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And also Lionel is a local journalist—I mean, is a journalist on campus.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Sure, that’s right. I think that might come—I don’t even know if that was particularly conscious, to be honest. But I knew that—I knew that what I wanted to talk about in this movie is culture and how culture affects our identities, and how identities come into conflict with who we are. And so, it was really important—I think where that comes from is that, you know, even the name of the movie, Dear White People, is sort of an admission that in a lot of ways black culture is in response to white mainstream culture. And so, you know, while I can’t say it was like—it was on purpose, I think that there’s—you know, subconsciously, there is a reason why the characters in some way are contributing to culture, whether or not it’s the black culture on their campus or the mainstream culture on their campus, because, you know, that, to me, is just a really interesting issue and, in many ways, like subversively dangerous. And yeah, so I think that’s where that came from.

AMY GOODMAN: As you introduced Dear White People here at Sundance, at its showings, you give white people permission to laugh.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, that’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you say?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: You know, I just say to all the white people in the audience, on behalf of all the black people in the world, you have the right to laugh. You get a free honorary black card with each Sundance ticket. Because it is—it’s meant to be a satire, you know? I think if you stop at the title, and you get the knee-jerk reaction—”Oh, this is just going to be an indictment, you know, an hour-long indictment”—you’re kind of missing the point. It’s the title of a movie, and I just want to put people at ease. It’s OK, you know? This movie is meant for people of all races to connect to. I think that the issue of being an other is a universal human experience. I happen to be talking about it from a black point of view, and just like every filmmaker is talking about whatever they’re talking about from their point of view. And that should make it no harder to watch or enjoy than any other movie.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what are you working on now? Or is it possible to even talk about that, since this is your first film? It has just broken out.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Yeah, it’s exciting. No, I am very hungry to get a few other stories to the screen. There’s a lot of things that I want to say. And I’m excited about all the possibilities after this film, particularly after this reception, to say—to say even more daring and interesting things.

AMY GOODMAN: How do you compare Dear White People, would you, last year a film based on real-life experience, though it was a feature film—and we usually cover the documentary track, but this was, you know, so significant, was Fruitvale, Fruitvale Station?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Absolutely, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Ryan Coogler

JUSTIN SIMIEN: I actually just met Ryan Coogler just now, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, he’s here.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: It’s very—yeah, it’s very crazy.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how do you compare what you did, Dear White People, with that?

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Well, first of all, they’re very different films. But Fruitvale, what is so brilliant, brilliant, brilliant, brilliant about that movie is that, because you know how it’s going to end at the beginning, you are watching this black man toggle his blackness and modulate his blackness around everyone—it’s like a game of survival. He’s one way with his mother. He’s one way with his friends.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, this is the film about Oscar Grant, who was killed by police at the Fruitvale station in California on New Year’s Day.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: That’s right. And he’s—

AMY GOODMAN: And he then fictionalizes it.

JUSTIN SIMIEN: Absolutely. And he’s all these different versions of himself for all these different people, in all these different situations. And he slipped up. He was the wrong version of himself at the wrong time, and he died because of it. And that’s a tragedy. And that’s what it’s like to be a black man in this country. And I think that that movie said that in such an eloquent and moving and beautiful, simple way. You know, to be even mentioned in the same, you know, reference with that film is an honor, because it really is a masterpiece. And, you know, I think that, you know, Ryan and I have very different approaches to talking about that issue, but it’s that pressure to be a different version of yourself all the time that I think, you know, our films share. We share that same message.

AMY GOODMAN: The director of Dear White People, Justin Simien, along with Marque Richardson, who plays the character Reggie in the film Dear White People. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where we interviewed them earlier this year. There, it won the U.S. Dramatic Special Jury Award for Breakthrough Talent. The film also played this weekend in New York at the New Directors/New Films festival. Lionsgate and Roadside Attractions have just bought the film.

And that does it for our broadcast. If you’d like a copy of the show, go to our website at democracynow.org. On Saturday, on March 29th, I’ll be speaking in St. Louis at 6:00 p.m. at the Gateway Journalism Review’s First Amendment Celebration. You can check our website for details. Hope to see you in St. Louis.

Media Options