Topics

Guests

- Col. Morris Davisretired Air Force colonel and the former chief military prosecutor at Guantánamo Bay. He resigned in 2007, shortly after he met with Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

- Nancy Hollanderlead lawyer for Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

- Larry Siemswriter and activist, and the editor of Guantánamo Diary. He is the former director of the Freedom to Write and International Programs at PEN American Center.

Links

- Book: "Guantánamo Diary" by Mohamedou Ould Slahi (Little, Brown and Company)

- Read chapter 1 of "Guantánamo Diary"

- Watch video about Mohamedou Ould Slahi produced by The Guardian

- Read Op-ed: "Where is justice for the men still abandoned in Guantánamo Bay?" by Col. Morris Davis

- See our vast archive of Democracy Now! reports on Guantánamo

- Read original manuscript written by Mohamedou Ould Slahi (posted by The Guardian)

After a seven-year legal battle, the diary of a prisoner held at Guantánamo Bay has just been published and has become a surprise best-seller. Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s diary details his experience with rendition, torture and being imprisoned without charge. Slahi has been held at the prison for more than 12 years. He was ordered released in 2010 but is still being held. “The cell — better, the box — was cooled down so that I was shaking most of the time,” he writes. “I was forbidden from seeing the light of the day. Every once in a while they gave me a rec time in the night to keep me from seeing or interacting with any detainees. I was living literally in terror. I don’t remember having slept one night quietly; for the next 70 days to come I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping. Interrogation for 24 hours, three and sometimes four shifts a day. I rarely got a day off.” We air a clip of a Guardian video about Slahi’s case, which features actors Colin Firth and Dominic West reading from his diary. We speak with three guests: Slahi’s lawyer, Nancy Hollander; book editor, Larry Siems; and Col. Morris Davis, the former chief military prosecutor at Guantánamo Bay, who says Slahi is “no more a terrorist than Forrest Gump.”

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: After a seven-year legal battle, the diary of a prisoner held at Guantánamo Bay has just been published and has become a surprise best-seller. The diary was written by a Mauritanian man named Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who has been held at the base for more than 12 years. He was ordered released in 2010 but is still being held. Later in the show, we’ll be joined by his lawyer, Nancy Hollander, and Larry Siems, who edited the diary.

AMY GOODMAN: But first, let’s turn to a new video produced by The Guardian. It features interviews with Nancy Hollander, Siems and Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s brother, Yahid. It begins with the actor Dominic West, best known for his role as Detective Jimmy McNulty in the TV show The Wire, reading the diary writings of Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Dominic West] The cell—better, the box—was cooled down to the point that I was shaking most of the time. For the next 70 days, I wouldn’t know the sweetness of sleeping: interrogation 24 hours a day. I was living literally in terror.

NANCY HOLLANDER: There is no reason for Mohamedou to be in Guantánamo. Mohamedou has never been charged with a crime. He’s been in Guantánamo now 14 years. It’s not that they haven’t found the evidence against him; there isn’t any evidence against him. Mohamedou started writing in 2005. He had prepared 90 pages in a notebook that the guards had given him. That was the beginning of this manuscript.

LARRY SIEMS: For a number of years, his attorneys conduct litigation and negotiations to get that manuscript declassified.

NANCY HOLLANDER: Mohamedou is somewhat of a modern Renaissance man. He is from the country of Mauritania. He’s from a very poor family, but he won a scholarship to study in Germany as a very young man.

LARRY SIEMS: Mohamedou had joined al-Qaeda in the early 1990s. Like many young men, he had gone to Afghanistan as a student to join the fight against the communist government of Afghanistan. And to join the fight, you had to train at an al-Qaeda camp. And he had trained, and he had sworn loyalty to them. But, as he’s said repeatedly, he broke all ties; after the communist government collapsed and the various mujahideen factions started shooting each other, Mohamedou essentially said, “I’m out.”

NANCY HOLLANDER: Mohamedou was at his mother’s house in November of 2001. And he gets a call from the police to come and be interviewed. And he literally, I’m sure, told his mother, “I’ll be right back.” And he disappeared. And his family has never seen him again to this day.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Dominic West] There were four of them when I stepped outside the door with my mom and my aunt. Both kept their eyes staring at me. It is the taste of helplessness when you see your beloved fading away like a dream and you cannot help him.

NANCY HOLLANDER: He realized he wasn’t going home when he got on an airplane, was stripped of his clothes. In August of 2002, he landed in Cuba, in Guantánamo. His family, of course, had no idea what had happened to him.

LARRY SIEMS: And it was only when Yahid, Mohamedou’s younger brother, who lives in Germany, picked up Der Spiegel and saw an article in October of 2002 that Mohamedou was in Guantánamo, did the family know where he had been held.

YAHID OULD SLAHI: [translated] We were all speechless. How can a government lie to us for so long and play such dirty games with us? We were all completely disheartened.

NANCY HOLLANDER: They were trying to frighten him so that he would tell them what they wanted to hear.

LARRY SIEMS: They would come to him, essentially, and say, “Well, we know what you did. We just need you to tell us.”

NANCY HOLLANDER: “We know you were involved in 9/11. We know you know these people.”

LARRY SIEMS: And they were on this kind of endless fishing expedition.

NANCY HOLLANDER: And there was no truth to tell them, but that’s what they kept saying.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Dominic West] “I’m going to do everything I’m allowed to to break you. You will never see your family again.” My answer was always: “Do what you got to do. I have done nothing.” And as soon as I spit my words, he went wildly crazy, as if he wanted to devour me alive.

NANCY HOLLANDER: Mohamedou was subjected to a whole list of torture techniques that had been approved by the secretary of defense.

YAHID OULD SLAHI: [translated] They told him they had taken my mother from Mauritania and put her in a single cell in Guantánamo. And if he didn’t give officials the information they expected, she would be severely tortured.

NANCY HOLLANDER: Significantly, they included what in Guantánamo was known as the “frequent flyer program.” And they called it that because they wouldn’t let people sleep. And they proceeded to torture him.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Dominic West] “Blindfold the [expletive] if he tries to look.” One of them hit me hard across the face, and quickly put the goggles on my eyes, ear muffs on my ears, and a small bag over my head. They tightened the chains around my ankles and my wrists; afterwards, I started to bleed. I thought they were going to execute me.

LARRY SIEMS: Just as Mohamedou had this remarkable journey, his manuscript has a fairly remarkable journey. He writes it in 2005.

NANCY HOLLANDER: We would get the book in bits and pieces.

YAHID OULD SLAHI: [translated] He started the book as a diary, and over the years the book became more detailed.

LARRY SIEMS: Every utterance of a Guantánamo prisoner is deemed classified from the moment of its creation.

NANCY HOLLANDER: What you have to do is send it back to what’s called a “privilege team.” And they read it and decide what can be made unclassified.

LARRY SIEMS: What I got in the summer of 2012 was the version of the manuscript that was cleared for public release, that had had these, you know, layers of censorship grafted onto it. You know, the physical impression of a page full of redactions is a brick wall. The amazing thing about Mohamedou and his writing is he has an incredibly strong, clear voice.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Dominic West] They brought me a chessboard so I could play against myself. When the guards noticed my chessboard, they all wanted to play me. And when they started to play me, they always won. The strongest among the guards taught me how to control the center. After that, the guards had no chance to defeat me.

NANCY HOLLANDER: He just hopes that someday he’ll be released. He’s in what I would consider a horrible legal limbo, and it’s just tragic. He needs to go home. If he gets out, he could come live with me. I would be happy to have Mohamedou in my house. He is just such a good, warm, caring human being. And somehow that strength keeps him going.

LARRY SIEMS: What’s remarkable about Mohamedou’s book is that we have a voice that’s come out of this void, and that it’s such a remarkable, humane and, I think, ultimately, forgiving voice. It’s a wonder.

YAHID OULD SLAHI: [translated] Sadly, this has taken so long. But we have never, and will never, lose hope. Never.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Dominic West] A Mauritanian folktale tells us about a roosterphobe, who would almost lose his mind whenever he encountered a rooster. “Why are you so afraid of the rooster?” the psychiatrist asked him. “The rooster thinks I’m corn.” “You’re not corn. You’re a very big man. Nobody can mistake you for a tiny ear of corn,” the psychiatrist said. “I know that, Doctor. But the rooster doesn’t.” For years, I’ve been trying to convince the U.S. government that I am not corn.

AMY GOODMAN: The actor Dominic West reading the diary of Guantánamo prisoner Mohamedou Ould Slahi. That video was produced by The Guardian. When we come back, we’ll be joined by Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s attorney, Nancy Hollander; the editor of the prison diary, the Guantánamo Diary, Larry Siems; and Colonel Morris Davis, the former chief military prosecutor at Guantánamo Bay. Back in a minute.

[break]

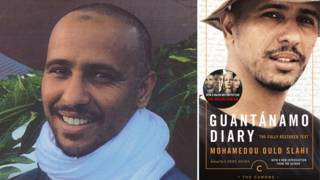

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We continue to look at the case of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a Mauritanian man who’s been held at Guantánamo for 12 years without charge. His writings were published this week as the book Guantánamo Diary. Slahi’s 466-page handwritten manuscript was initially classified by the U.S. government and heavily redacted before publication.

AMY GOODMAN: It was held for more than seven years before it’s been released. We’re joined now by three guests. Nancy Hollander is Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s lead lawyer. Larry Siems is editor of Guantánamo Diary. And Colonel Morris Davis is the former chief military prosecutor at Guantánamo Bay. He resigned in 2007, shortly shortly after he met with Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

We welcome you all to Democracy Now! Colonel Morris Davis, talk about who Mohamedou was, how you met him there. And did your resignation have anything to do with him?

COL. MORRIS DAVIS: Yeah, I met him early in 2007. As we were preparing, you know, the prosecution of the military commission cases at Guantánamo, we were interested in potentially finding a detainee or detainees who would be cooperating witnesses. And I was told that Slahi and his partner, Tariq al-Sawah—they lived in a compound of their own—that the two of them were candidates, potential candidates, to cooperate with the prosecution. So I met with Mr. Slahi probably three or four times over a course of several months and got to know him probably as well as any of the detainees that I had contact with at Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: And what was your impression of him? How did he affect you?

COL. MORRIS DAVIS: Well, it was really an interesting contrast. He and Tariq al-Sawah lived together in a compound of their own. You know, at the time, back in 2007, Guantánamo was supposed to be this super-secret facility that you couldn’t really talk about, but you could go on Google Earth, and if you knew what you were looking for, you could drill down and see their compound where they lived and their vegetable garden that was between their two huts where they lived. They were a sharp contrast. Mr. Slahi is maybe five-foot-six and weighs about 110 pounds last time I saw him, and Mr. Sawah was probably six feet tall and weighed over 350 pounds. So just their physical appearance was like the odd couple. And personality-wise, as well. Mr. Sawah was polite and would—if you ask him something, he would respond, but he didn’t carry a conversation, where with Mr. Slahi the problem was—wasn’t getting him to talk, it was getting him to stop, because he was very, very gregarious. As you can see from the diary, he’s very articulate, very bright.

And, you know, it was always a pleasure to meet with him. I mean, every time I went—I mentioned in the article I wrote for The Guardian that every time I went, he had to make tea, using mint leaf from the garden. And, you know, Guantánamo was always hot and humid, and I was in uniform, and I’m not a tea drinker to begin with, but I’d have to sit and drink hot tea and sweat in the sun and chat with Mr. Slahi.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Nancy Hollander, you’ve been Slahi’s legal representative since he’s been allowed legal representation—that is, since 2005. Can you tell us how you came to work on this case and how it is that he’s been held for 12 years and has yet to be charged with anything?

NANCY HOLLANDER: I came to work on this case because a lawyer in France, a lawyer named Emmanuel Altit, sent me an email saying that he had heard from a lawyer in Mauritania, Mr. Ebety, that the family of Mohamedou thought he was in Guantánamo, and that now that the prisoners could have lawyers, would I consider seeing if I could represent him. I found him. I found that he had been assigned to another lawyer by the Center for Constitutional Rights. That lawyer was Sylvia Royce. And although Sylvia left the team later on, at the beginning the two of us made arrangements to go to Guantánamo.

And our first visit was perhaps the one that sticks in my head the most. We went. It was our very first visit to Guantánamo for both of us. We walked into the hut. The guards opened the door, and there was Mohamedou. And he stood up, and he smiled, and he put his arms out as though to walk up to embrace us. But he didn’t move. And we stood there for a moment, and then I realized, to my horror, that he was chained to the floor, with chains around his ankle, and couldn’t move. So he could just stand there and smile. And we walked into his embrace, and he hugged us. I think we were the first people he had hugged in several years. And then he gave us these first 90 pages as a way for us to know about him, to know something about him and what had happened to him. And that’s how—that’s how this book began. And we encouraged him to keep writing, and then he continued to write.

AMY GOODMAN: Nancy Hollander—

NANCY HOLLANDER: He has never been charged with—I’m sorry.

AMY GOODMAN: He’s never—you were saying he’s never been charged with a crime. Nancy Hollander, can you describe what happened to him when the U.S. detained him, first before Guantánamo and then at Guantánamo? In Guantánamo Diary, Slahi’s book, he says one of the interrogators said, quote, “I know I can go to hell for what I do to you.”

NANCY HOLLANDER: Well, what that guard was referring to was specifically not letting him pray. One of the things that was on the list of special interrogation techniques that the secretary of defense, Donald Rumsfeld, approved specifically for Mohamedou was that he not be allowed to pray. He was also put in what they called their “frequent flyer program,” which meant he was not allowed to sleep. He was interrogated around the clock, and maybe he would get an hour or two of sleep, and then they would wake him up. So this went on for almost two months, or maybe even longer.

They dragged him out on a boat. First they came into his cell with a dog, terrified him, put a hood over him, put goggles on, put ear muffs on, dragged him. We were able to learn from his medical records that he complained that his ribs were broken, and in fact they were broken, on that, when they beat him. And they took him out, and he was, as he says in the book, afraid that they were going to dump him in the ocean or take him to some other place. For a long, long time, they did not tell him he was back in Guantánamo. They beat him. They terrified him. They put ice down his clothes. They kept him in cold rooms, then they kept him in hot rooms. They knew that he had a back issue from a previous injury and that the doctor in Guantánamo had ordered that he not have to stay in certain positions, and they used that. And those were the positions they put him in, precisely what they knew he was not supposed to be in. The litany goes on and on of what they did to him.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But, Nancy, even before Slahi got to Guantánamo, he had been detained for almost a year. He was picked up on his way from—I believe from Canada to Mauritania, he was picked up in Senegal. Then he was detained in Mauritania, then sent to Jordan, under the CIA’s extraordinary rendition program, for seven-and-a-half months, then from there to Bagram, and from Bagram to Guantánamo. Can you describe what happened in the course of his going to Guantánamo?

NANCY HOLLANDER: Well, he was picked up twice, first in Senegal, when he left—when he left Montreal, he flew to Senegal, and that’s where his family was going to meet him to drive home to Nouakchott in Mauritania. He was detained there. Then later, he was detained again in Mauritania. And then, finally, he was at his mother’s house—and this was the third time—and he got another call from the police station, then the police chief. And they said, “Would you come and talk to us? And bring your own car. We’re sure you won’t be staying long.” And he never went back.

They took him to Jordan. He was there for seven-and-a-half or eight months. He was interrogated there. He was not tortured in the same way, but he was put in a cell where he could hear other people screaming and crying, and was terrified every moment that he was there.

And then, suddenly, another plane comes. He thinks he’s going home. And in fact he ends up in Afghanistan for a couple of weeks and then goes to Guantánamo. And at that time, the government was claiming that it was taking people from the battlefield in Afghanistan, which of course wasn’t true—only about 5 percent of the people in Guantánamo were ever actually on a battlefield—but he came from Afghanistan in a harrowing airplane ride to Guantánamo and was interrogated as soon as he got there, and then was interrogated and tortured. And even after he agreed to tell them whatever they wanted to hear, they continued with their—what he called “the recipe of torture.”

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to—

NANCY HOLLANDER: But he was never charged, ever charged with any crime.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to a comment from Slahi’s brother, Yahid Ould Slahi. He spoke to the BBC and said he was most upset with the Mauritanian government about what happened to his brother.

YAHID OULD SLAHI: [translated] I think they sold him to the Americans, and they lied the whole time to us. They told us that Mohamedou was still in prison in Mauritania, while he was being tortured in Guantánamo Bay. I read the news in Der Spiegel magazine whilst I was at university in Germany, and I couldn’t believe it. My mother had been taking money and food to the jail every day in Mauritania, because they told her that Mohamedou was in there. I called my family, and I told them that my brother was actually in Guantánamo Bay, but they didn’t believe me. They didn’t believe me until 2002, when they got a letter from my brother from the prison in Guantánamo.

AMY GOODMAN: That is Yahid Ould Slahi, the brother of Mohamedou, who is still in prison at Guantánamo, over 12 years without charge. Colonel Morris Davis, you have referred to Slahi as a kind of Forrest Gump. What do you mean?

COL. MORRIS DAVIS: Well, as was mentioned earlier, you know, he was a—went to Germany. He was in and around Hamburg. You know, the Hamburg cell of al-Qaeda was affiliated with 9/11. You heard, I think, Nancy mention that he was in Montreal, which was in and around Ressam and the millennium bombing plot. So, he turned up in places where there were significant events related to terrorism that were taking place, kind of like Forrest Gump. You know, anytime there’s a historical event, somewhere in the picture you’d see him in the background. And Slahi was kind of the same way. He showed up at the right time in the right places.

But when we were looking at him potentially being a cooperating witness, myself and some other members of the prosecution team went out to the National Counterterrorism Center with a group of other people, and we had a briefing from the agents that had spent years investigating Slahi’s case. And we went through the whole litany of, you know, where he’d shown up. But their conclusion was that there was a lot of smoke and no fire, that there are odd circumstances where he showed up in places, but there was absolutely no evidence that he had ever engaged in any acts of hostility towards the United States. And the conclusion was there was simply nothing that we could charge him with.

And as you said, you know, for more than a dozen years now, he’s been sitting at Guantánamo. And one of the real ironies is, there have been six men that have been convicted of war crimes at Guantánamo in the military commission. Five of those six are back home in their home countries. So it’s a sad commentary on America, where you’re better being a convicted war criminal than someone who’s never been charged at all.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Colonel Morris Davis, could you explain how it is that he was initially—Slahi was initially considered a high-value target, but then when it came to the point where an attempt was made to charge him or to prosecute him, as you point out, there wasn’t sufficient evidence? Could you talk specifically about the role of Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Couch and his role in this?

COL. MORRIS DAVIS: Right, yeah, I became the chief prosecutor in September of 2005. I was the third chief prosecutor. They’re currently up to the sixth chief prosecutor. But at the time I came on board, Lieutenant Colonel Couch had been a member of the prosecution team for a year or two before I got there. And one of the cases that he’d been assigned was the Slahi case. And after reviewing the evidence, you know, he was convinced that there was insufficient evidence to bring charges, and he was also convinced that Slahi had been tortured. So, for both reasons, he had concluded it was a case that couldn’t be prosecuted.

And when I came on board, you know, he briefed me on the case, and I came to the same conclusion. And that was just reinforced later, as I said, when we got the briefing at the National Counterterrorism Center and all of the agencies involved agreed that there just wasn’t a case to be had against Slahi. But again, he showed up at places, like Hamburg and Montreal, where there were significant events, and I think that’s what led to the suspicion that he had to be a high-value detainee, that he was in and around these places where significant events that took place, and if only we could torture him, and, you know, he would spill the beans, and we’d find bin Laden, and everything would work out fine. And that just simply wasn’t the case.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it’s just astounding. You quit eight years ago as the chief military prosecutor at Guantánamo, having decided not to bring charges against him, and he is still there, actually there for more than 12 years, which brings us to Larry Siems, who is the editor of this astonishing book called Guantánamo Diary. You know, sometimes we get on the air, we say a book has just come out to rave reviews, it’s a best-seller, and we interview the author. We cannot interview the author, because he’s at Guantánamo. But we can talk to you, who worked on the text. The cover of Guantánamo Diary, you see his handwriting behind it. It’s in English. Where did Mohamedou learn English?

LARRY SIEMS: English is Mohamedou’s fourth language. He—born in Nouakchott in Mauritania, he spoke Arabic and French. He studied in Germany, and so he was fluent in German. He learned English in U.S. captivity. This is a language that he learned from the United States, from his captors.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Larry, on the back of the book, John le Carré describes this work as, quote, “A vision of hell, beyond Orwell, beyond Kafka.” So, could you explain how you first came across his writing and what made you decide to work on this text?

LARRY SIEMS: Sure. I actually came to Mohamedou’s story through another set of documents entirely, which was the U.S. government’s own documents. From 2009 to 2012, I worked with the ACLU on this project called “The Torture Report.” The ACLU had managed to excavate 100,000 pages of formerly classified government documents about the abuse of detainees in Guantánamo, in Afghanistan, in Iraq and in the CIA black sites. But it was kind of—it was just raw data. And my job was to try to sort of go through that and find stories, weave together stories of individual characters, to find the human beings that were, you know, involved in these documents.

And one of the people that emerged most clearly was Mohamedou Ould Slahi, because Mohamedou, as we’ve said, was one of the most abused prisoners in Guantánamo. He was one of two prisoners designated for this special project interrogation by defense intelligence agents. That interrogation, the plan of which was signed, as Nancy said, by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld himself, that plan was written, revised, meticulously. It involved everything that Nancy described—extreme isolation, sleep deprivation, cold rooms, loud music, strobe lights, death threats, threats—ultimately, a threat to his mother. They came to him—his chief interrogator came to him posing as a Navy captain who was an emissary from the White House, handing him a letter that said, “Mohamedou, we have your mother. We’re bringing her to Guantánamo. She’ll be the first woman in Guantánamo, and you can imagine what will happen to her in Guantánamo.”

All of those things were calculated and written out ahead of time in government documents, and then, of course, meticulously detailed, as torturers are perversely prone to do, in all of the daily reports from those interrogations. We had all those documents by 2008, 2009, mostly because of two large government investigations, one by the Justice Department that was prompted by FBI agents inside of Guantánamo complaining about the treatment that the Pentagon interrogators were starting to mete out in Guantánamo, patterned on the CIA’s black site enhanced interrogations, and then from a Senate Armed Services Committee report. Both of those reports have many pages about Guantánamo—about Mohamedou’s story, so I knew the broad outlines of it.

I also had, in those—from those documents, little hints of his voice. And it’s very, very—you realize how absolute the censorship is around Guantánamo. And one of those things is—part of the reason is to keep us from hearing those voices. But in those documents, there were two in particular that were transcripts from his hearings before review boards in Guantánamo. And one of them was from 2005, his Administrative Review Board hearing. He’s quite a humorous guy. He makes a couple of good jokes in there. And then he tells the presiding officer, he said, “Oh, by the way, I’ve written a book. You know, they sent the book to Washington. You know, it’s classified, but it will be cleared for release. And when it’s cleared, you should read it. It’s a really interesting book, I think.” He says this in 2005. As Nancy said, it’s held for seven years. And then, finally, after this process of—you know, of litigation and negotiation that Nancy’s team carried out, in 2012, after I had finished this torture report, I got a call from them, saying, “We have this manuscript. Would you like to see it?” And I said, “Yes, please.”

AMY GOODMAN: And you take it from there. How much of it was redacted? Was he able to see the final edited version?

LARRY SIEMS: There are about 2,600 black bar redactions in the book, varying from one word to many pages. I was not able to communicate with him. I sent him a letter, at one point, introducing myself and saying that I had been asked to work on this and I hoped we could correspond, and I never heard anything. I have no idea whether he received that letter.

When I had finished my draft of an edit of the manuscript, I officially—I, you know, petitioned the Pentagon to be allowed to visit him just once, using—you know, according to whatever security protocols they wanted, just so I could sit with him and sort of go through and make sure that he approved of the shape of the final manuscript, because I think it’s a dead basic right, as Mohamedou would say, of any writer to have the final say about how his words appear in print. I had, for years, worked as the free expression director at PEN American Center, and I am, above all, a free expression advocate. So I thought he would have that right to do that. The Pentagon refused to allow me to visit him, citing, as they have done for every journalist and writer who’s tried to visit a detainee—citing, quite ironically, the Geneva Convention’s prohibition on making detainees into public curiosities. That was their basis for denying me the right to visit him.

AMY GOODMAN: Mohamedou’s mother died in 2013. Nancy, can you talk about Mohamedou’s reaction and what he tried to do to see his mother?

NANCY HOLLANDER: It was really tragic, because we found out from his lawyer in Mauritania that his mother had died, and his family was really afraid to tell him that she had died. They were afraid of how—he was very close to his mother. Of course, that’s what the government knew, and that’s why they came up with this fake letter in the beginning. And they were afraid to tell him. We actually had the responsibility of telling him. We arranged for a phone call. To arrange for a phone call from counsel, you have to have an emergency, and then it takes about 15 days to get the call. We were able to make a call to him. It was a call with someone from the government on the line, so it was not a privileged call, attorney-client privilege. But we actually told him about his mother.

He was very upset. He was upset both, of course, that she had died and that his family had not told him. And they were so conflicted. They were so afraid that it would take him over the edge to know she had died. And as you can see, he dedicated this book to her, which I assumed he would want to do. And, you know, it’s really important to see that even though he wrote the book in 2005, if you read the little afterword, he wrote that in 2014 and gave it to another member of our team, Linda Moreno, when she went to visit him. And he’s still a forgiving person. He still wants to sit down and have a cup of tea with the people who are mentioned in this book. It’s so incredible that he is so compassionate even to this day. And I think that humanity in him is what keeps him going.

AMY GOODMAN: His relationship with his torturers, Larry. Joe Nocera of The New York Times review of books—in the New York Times’ review of his book, said he “come[s] across as fair to all, even [to] his torturers.” And yet, you’ve described him as one of the most abused prisoners at Guantánamo.

LARRY SIEMS: I think that’s one of the most extraordinary things about this book. If you hear that you’re going to read a diary by one of the most abused prisoners in Guantánamo, you’re braced for a lot of darkness. No question about it. And the story that Mohamedou tells is very, very dark. But his personality is the opposite. He is an optimistic person. He’s a curious person. He’s constantly pulled out of himself by his surroundings, by the people he interacts with. He likes people. He has a fundamental ethic of treating everybody as an individual, no matter who they are or what team they’re supposedly playing for. He says, you know, he understands human beings are made up of a combination of good and evil—everybody is—it’s just a question of what percentage, you know?

And his interactions with—you know, the amazing thing about this book is how it gives us the human drama of Guantánamo. And it’s a very, very human drama. And for me, I think the revelation of the book is that this is our drama, as well. And the characters in this book are American servicemen and American servicewomen and intelligence officers whose voices we’ve never heard before, who are put in these positions, you know? And his portraits of our brothers and sisters and sons and daughters, you know, are remarkable. And you realize how much we’ve put on them and how much they must be suffering for what we’ve asked them to do.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, let’s go back to Mohamedou Ould Slahi in his own words. This is the Oscar-winning British actor Colin Firth reading an excerpt from Guantánamo Diary.

MOHAMEDOU OULD SLAHI: [read by Colin Firth] So has the American democracy passed the test it was subjected to with the 2001 terrorist attacks? I leave this judgment to the reader. As I am writing this, though, the United States and its people are still facing the dilemma of the Cuban detainees.

In the beginning, the U.S. government was happy with its secret operations, since it thought it had managed to gather all the evils of the world in GTMO, and had circumvented U.S. law and international treaties so that it could perform its revenge. But then it realised, after a lot of painful work, that it had gathered a bunch of non-combatants. Now the U.S. government is stuck with the problem, but it is not willing to be forthcoming and disclose the truth about the whole operation.

Everybody makes mistakes. I believe the U.S. government owes it to the American people to tell them the truth about what is happening in Guantánamo. So far, I have personally cost the American taxpayer at least one million dollars, and the counter is ticking higher every day. The other detainees are costing more or less the same. Under these circumstances, Americans need and have the right to know what the hell is going on.

Many of my brothers here are losing their minds, especially the younger detainees, because of the conditions of detention. As I write these words, many brothers are hunger-striking and are determined to carry on, no matter what. I am very worried about these brothers I am helplessly watching, who are practically dying and who are sure to suffer irreparable damage even if they eventually decide to eat. It is not the first time we have had a hunger strike; I personally participated in the hunger strike in September 2002, but the government did not seem to be impressed. And so the brothers keep striking, for the same old, and new, reasons. And there seems to be no solution in the air. The government expects the U.S. forces in GTMO to pull magic solutions out of their sleeves. But the U.S. forces in GTMO understand the situation here more than any bureaucrat in Washington, D.C., and they know that the only solution is for the government to be forthcoming and release people.

What do the American people think? I am eager to know. I would like to believe the majority of Americans want to see justice done, and they are not interested in financing the detention of innocent people. I know there is a small extremist minority that believes that everybody in this Cuban prison is evil, and that we are treated better than we deserve. But this opinion has no basis but ignorance. I am amazed that somebody can build such an incriminating opinion about people he or she doesn’t even know.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Oscar-winning British actor Colin Firth reading an excerpt from Guantánamo Diary. I wanted to end with Nancy Hollander. In 2010, Nancy, The Washington Post wrote, “Sawah, now 52, and Slahi, now 39, have become two of the most significant informants ever to be held at Guantanamo. Today, they are housed in a little fenced-in compound at the military prison, where they live a life of relative privilege—gardening, writing and painting—separated from other detainees in a cocoon designed to reward and protect.” Can you explain that?

NANCY HOLLANDER: Well, I’m really not at liberty to talk about Mohamedou’s living conditions. I can tell you that when he was tortured and when they finally brought him this fake letter from his mother, he said, “I’ll tell you anything you want.” And then he told them anything they wanted to hear. But it was really information they fed him. “You did this, didn’t you? You did this, did you? We just need you to tell us that you did it.” So he said, “I did it.” And it was all lies, because he hadn’t done any of it. He lives in Guantánamo in a prison, in a prison cell every single day of his life. And since 2010, since the day that Judge Robertson ordered him to be released, he should have been released. And the government of the United States should stop fighting against that release and release him now.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Nancy Hollander, before we conclude, very quickly, what seems to be at issue then? Is it the case that the U.S. government still says that he has maintained his links to al-Qaeda, whereas he says he has severed them? How is it that he is still detained years after a judge has said he—a U.S. judge has said he should be released, or that there’s nothing to charge him?

NANCY HOLLANDER: Well, you’re correct that the government maintains that when he swore allegiance to fight in Afghanistan in 1990, which, I might add, the United States supported that fight financially and militarily, he—that that was it, that he still maintains—the government still maintains that he’s part of al-Qaeda. And the court of appeals has made the test so broad and so loose that it’s almost impossible to fight against that. And the government keeps forcing that standard to be looser and looser. So, it’s really the government, it’s the Obama administration and the military, that need to step up and stop fighting these habeas cases, particularly in Mohamedou’s case, where the district judge found that in 2010, after he had already been held for many years, the government had already gathered all the evidence it was ever going to gather, that it didn’t have the evidence to even object to this habeas, which is a very low standard. So, the government needs to step up and release him.

AMY GOODMAN: Last seconds, Larry Siems?

LARRY SIEMS: I mean, for me, the most disturbing question is: To what extent has he been held all this time, simply that he’s not able—so he’s not able to tell the story of what happened to him? You know, Guantánamo is a story about secrecy. It’s created in secrecy. It was created in order to allow abuse to happen. Then it was perpetuated in order to cover up that those abuses had happened. It’s being prolonged, I think, finally, to prevent accountability for those abuses. And all that time, we’re perpetuating and prolonging grievous mistakes, and it needs to stop.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we’re going to leave it there. Larry Siems is the editor of Guantánamo Diary. We hope soon to be speaking with the author; he is Mohamedou Ould Slahi. Larry Siems is the former director of the Freedom to Write and International programs at PEN American Center. Nancy Hollander, thanks so much for joining us, Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s lead lawyer. And thank you so much to Colonel Morris Davis, retired Air Force colonel, former chief military prosecutor at Guantánamo Bay. He resigned in 2007, shortly after he met with Mohamedou Ould Slahi.

This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute with what some are calling the Guantánamo Bay in the Pacific. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Shaker Aamer,” a song written for another longtime Guantánamo prisoner by British musician PJ Harvey. Shaker Aamer has been held since 2001 without trial or charge, despite being cleared for release by President Bush in 2007 and President Obama in 2009. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

Media Options