Guests

- Art Spiegelmanrenowned American cartoonist, editor and comics advocate best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus. He was co-editor of the comics magazines Arcade and Raw as well as a contributing artist for The New Yorker. In 2006, he wrote an article for Harper’s Magazine titled “Drawing Blood: Outrageous Cartoons and the Art of Courage.”

- Tariq Ramadanprofessor of contemporary Islamic studies at Oxford University. He is the author of a number of influential books on Islam and the West.

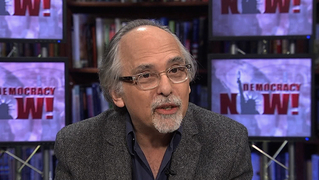

We continue our coverage of the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris by looking at the magazine’s background and its controversial history of satire. We are joined by two guests: Art Spiegelman, the renowned American cartoonist, editor and comics advocate whose Pulitzer Prize-winning “Maus” is considered one of the most important graphic novels ever published and one of the most influential works on the Nazi Holocaust; and Tariq Ramadan, a professor of contemporary Islamic studies at Oxford University and one of Europe’s most prominent Muslim intellectuals.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I want to turn to Stéphane Charbonnier, the editor of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo. He was among the 12 who were killed on Wednesday. In 2012, Charbonnier appeared on Al Jazeera and defended his publication’s decision to publish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad.

STÉPHANE CHARBONNIER: [translated] It’s been 20 years that I am part of this newspaper. It’s been 20 years that we have, quote-unquote, “been provocative,” on many different subjects. It just so happens that every time we deal with radical Islam, we have a problem, and we get indignant or violent reactions. We are in a country of the rule of law. We respect French law. Our only limit is French law. It’s that which we have to obey. We haven’t infringed French law. We have the right to use our freedom as we understand it.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: That was Stéphane Charbonnier, the editor of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo, who was killed in yesterday’s attack.

We are joined now by Art Spiegelman, the renowned American cartoonist, editor and comics advocate. In 1992, he won a Pulitzer Prize—he won the Pulitzer Prize for Maus, considered one of the most important graphic novels ever published and one of the most influential works on the Holocaust. Spiegelman also founded the comics magazine Raw. In 2005, he was named one of the hundred most influential people by Time magazine.

So, Art Spiegelman, could I begin by asking you to kind of situate this magazine, Charlie Hebdo? What kind of work did they do? How did they fit into the broader public sphere in France?

AMY GOODMAN: And why are they called Charlie Hebdo?

ART SPIEGELMAN: OK. They had been called Hara-Kiri. That was a satirical magazine in the '60s, way off to the wonderfully lunatic fringe of—it's something like the National Lampoon or something, far, far over the edge compared to, say, The Onion. I would say the only thing in American culture—somebody brought up this analogy for me when I talked to them yesterday—is South Park. South Park is closer to the spirit of Charlie Hebdo than anything else in American culture, in that to say that they’re provocative is to say their mission statement. Hara-Kiri had a subtitle, which was le journal bête et méchant, “mean and nasty.” And their point was not to afflict the afflicted, as was just coming up from Mr. Ramadan as an idea that somehow, oh, well, the Muslims are outsiders, they have no real power in France, and therefore they were subject to these cartoon attacks. Quite the contrary.

The reason that they changed their name was Hara-Kiri published an anti-Charles de Gaulle cartoon the minute after his death. It was kind of, in the France in which Charles de Gaulle was France, this was beyond whatever mourning—America went through its own conniption fit when Ronald Reagan died. Even NPR was off and sanctifying him. Charles de Gaulle, who maybe, arguably, there might have been more reason to sanctify in France, was—he died a week after a horrible fire in a discotheque in a small town in France in which 20 people or so died. And the headlines all over France were, whatever town it was, “Tragedy in (whatever town it was), 20 dead.” And the next week Charles de Gaulle dies, and the cover of Hara-Kiri is “Tragedy in Paris, One Dead,” keeping these people equivalent. That enraged France so much that that magazine was muzzled and censored and not able to come out the week after. But the week after that, they said, “OK, no problem, we’ll just change the name.” And from what I understand, and the magazine that I know, did reprint Peanuts at a time where that seemed interesting to do in the late '60s in France. And they just, “OK, if we're Charlie Hebdo, then we’re out again, because they only banned Hara-Kiri,” exactly the same magazine, new title.

AMY GOODMAN: And the name “Charlie”?

ART SPIEGELMAN: Charlie, I believe, comes from Charlie Brown. What you mentioned before we came on the air is interesting, and maybe they had that in mind. It’s more than I know. But I would like to point out—

AMY GOODMAN: Did it also have to do with Charles de Gaulle?

ART SPIEGELMAN: That’s what I mean, yeah—oh, I’m sorry, that’s what you had said off the air, and that seemed like a possible explanation. But the magazine I know always had Peanuts in it. So, I believe it could have come from either.

But the point that was most important about it was the relentlessness of their taking on whatever targets came into view. And I think that when we talk about provocation, the biggest provocation, of course, was putting Salman Rushdie under fatwa, the riots, the deaths that happened all over the world after the cartoons were published in the Jyllands-Posten, which were intended as a provocation in a different way than the one engaged in by Charlie, because their provocation in the Jyllands-Posten really was afflicting a minority in their culture. It was covered, I think, wallpapered over by, “Well, we have to have the right to portray Muhammad in our secular country,” but the reasons for doing it had more to do with the other inside an otherwise rather homogenous country, Denmark.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But why do you make the argument—I mean, that’s exactly what you wrote in that Harper’s piece—

ART SPIEGELMAN: Yeah.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: —-right, in 2006? And in the case of the Danish cartoons, it was, you know, afflicting the afflicted in Denmark, whereas in France now with these cartoons and what Charlie Hebdo does, you don’t think it’s the same. What is the distinct—-how do you compare the two publications?

ART SPIEGELMAN: OK, the mission—the mission of the Jyllands-Posten was to be a conservative right newspaper. The mission of Charlie was not even necessarily to be left-wing. You know, it was—their mission is to rant against all authority. You know, they’re asking for a radical kind of freedom that we don’t get in America very often. That’s why South Park might be closer. South Park is one of the places that did try to show the Prophet Muhammad right after the problems that came from the Danish cartoons. But they did it because they were told not to. This is like the great adolescent impulse. It’s not a sophisticated dialectic about freedom of speech. It’s just taking it for granted that we must have freedom of speech to be able to do what we do, and as a society and culture. And they’ve gone after every religion possible. They’re equal-opportunity defamers. And politically, they’ve gone after both sides. Houellebecq is on their side of the ledger, let’s say, politically, and yet the cover is mocking him, that was out the week that this all happened.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So could I just ask you to respond to what Tariq Ramadan said earlier, that it’s permissible to say things about Muslims in the public sphere in France, that it’s not permissible—because you just made the opposite case—that it’s not permissible to say about Jews, for instance, because it’s branded as—

ART SPIEGELMAN: Well, there’s a kind of touchiness about Jews that has to do with the fact that they were collaborators during World War II, so that makes them have a guiltier conscience there. Nevertheless, I mean, I remember when the mass graves were found in Srebrenica. The Charlie Hebdo cover that week was “How Can You Call It a Concentration Camp When There Isn’t Any Orchestra?” That was their headline. So, it’s hardly a magazine that’s trying to, like, afflict the afflicted. It’s a magazine that’s just trying to afflict. It’s trying to take full advantage of the ability to stir things up. And that’s—in a world where everything is stirred up, I’ve heard all of these discussions about, “No, no, no, we mustn’t stir things up, because it’s such a fraught situation.” But what are we supposedly—in our culture clash of civilizations, we’re not trying to find a culture that’s so repressed it can’t function; it’s one where we have to look at various issues from various points of view.

And what’s interesting to me is how great cartoons are at doing that, where it puts things in a high relief. And when they’re in a high relief, you can see them. You can then surround them with lots of words trying to contain them. But the images cut past all that. They move so directly into your brain that there’s no place to avoid them. They’re in there. Then you try to, like, put this salve around them, which is language. And that’s where we got that—whatever the currency rate has, a thousand words for each picture? Takes 10,000 words, because pictures keep leaking out in ways that weren’t intended even by the artist making it, but that are thereby functional—functioning as Rorschach tests for what actually are we living through right now. And it does that in a way that is so high relief that you can’t avoid it. And that allows us to have, hopefully, more language, more pictures, until these things all settle. The idea isn’t for it to turn into Kalashnikovs. I don’t think that was Charb’s goal, although he was willing to stand by the consequences of his magazine’s operating philosophy.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, do you think, Art, that there’s anything—you know, there’s a principle of what’s called hate speech. Do you think that can ever apply to cartoons?

ART SPIEGELMAN: It does, and it has, even in France, where they—actually, my French wife and I debate this all the time, because I, along with Rick, was going, “Man, the Skokie thing really stinks,” marching on a small town outside of Chicago that had a large Holocaust-surviving population. Having the Nazis in America choose that as their place to entertain their own rights of free speech was a dismal thing to do. And yet, OK, that’s the line, and we have to live by that line. I have to live with anti-Semitic caricature. There’s a lot of it in Islamic countries, incidentally. And I think that it’s part and parcel. You then have to, like, counter it. I think Maus functions as a counter to the anti-Semitic cartoons, while ruffling a lot of Polish feathers, for example.

AMY GOODMAN: And in a nutshell, the description of Maus, your Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel?

ART SPIEGELMAN: Oh, in a nutshell, yikes. OK, it’s a narrative about my father and mother’s experiences as Jews in Poland and how that passed down to me as a story, and me trying to understand that story as a cartoonist by giving it visual shape. The visual shape involved borrowing, actually, some anti-Semitic caricature, viewing Jews as rodents, so all the Jews are portrayed as mice, sometimes rat-like mice, in Maus. The Germans are portrayed as cats, because I grew up with the Tom & Jerry cartoons that gave me my operating system. And the Poles were portrayed, actually, as pigs. So these are all, except for the cats, defamatory caricatures by definition. Within the course of the book, I insisted that these animals stand upright and insist on their humanity. So, Poles who behaved incredibly well in the narrative my father was telling me about what happened to him are portrayed as behaving incredibly well. And these things are portrayed even visibly in the course of the book as Woolworth masks, with little strings hanging off the back of the masks. So these are masks of animals that are reducing people to their racial, ethnic, national stereotypes, and within that there are us poor, fraught humans acting whichever way we act, in some cases Jewish policemen behaving rather badly, Poles behaving rather well, even a German with a qualm of conscience, as that came up in the story, while still portrayed in his Nazi cat uniform.

AMY GOODMAN: Tariq Ramadan, when you listen to Art Spiegelman, your thoughts?

TARIQ RAMADAN: No, look, I cannot agree with him on one point, the way he is describing Charlie Hebdo. He’s talking about Hara-Kiri, that was much before Charlie Hebdo became what it is now. Why don’t you say in 2008 that one of the cartoonists was fired because he dared to say something about the—connecting this to the son of Sarkozy and making a joke about the fact that, you know, he was a Jew? And he was fired. So, tell me and give me one example over the last few—two years, for example, coming from Charlie Hebdo targeting another community than the Muslim community, because it’s easy.

And we know that also, just to be clear on that, they had financial problem, and these controversies and ongoing controversies, they were making some money out of it. And I am not saying this as somebody who is outside. This was said by many, many people, saying they are going too far with a target. So, to tell me today that they were courageous, no, don’t talk about Cavanna, what he did—

ART SPIEGELMAN: No, after—after their offices were firebombed, I think all bets are off in terms of discourse. At that point, they were mandated to respond.

TARIQ RAMADAN: No, no, it’s the last six years. The last six years, they have been targeting mainly the Muslim—

ART SPIEGELMAN: You know, I don’t read Charlie Hebdo. I don’t read French that well, so I have to only look at the pictures, and pulling from that.

TARIQ RAMADAN: So, it’s—no, no, I’m sorry.

ART SPIEGELMAN: But I’ve seen anti-Semitic caricatures in Charlie Hebdo in the last six years. So, that’s not true.

TARIQ RAMADAN: No, no, I can tell you that six—so tell me. Tell me, why did they fire somebody? And the question was freedom of expression. And, you know, their response was what, coming from Philippe Val, who is now the director of France Inter? Saying, “No, there are limits to freedom of expression.” This was six years ago. And you are telling me now that they are not—they are freedom—

ART SPIEGELMAN: That’s why he’s not the head of Charlie anymore.

TARIQ RAMADAN: No, no, no. That’s the point. That’s the point. It’s not because of this, because the president gave him the direction of France Inter, if you just look at the dynamic with him. So the point here, once again, is for us to say, please, if this is your take on equal treatment, we have to go as far as to assess this on facts, not on the past of this magazine.

ART SPIEGELMAN: OK, I agree—I agree that it’s more seemly when the power and poison of cartoons are directed at the powerful. And that’s the point I was making, actually, in the Harper’s piece that came up before. And yet, Siné, speaking of making money and whatever, that way of stomping on the impulses there, very cheerfully went on and did Siné Hebdo the week or two after. He started his own countermagazine that has been functioning—right after that, it was functioning quite well. And so, in the larger society, there’s room for your Muslim anti-Semitic cartoons, for French anti-Semitic cartoons, as well as all others, but the operating system—

TARIQ RAMADAN: No, no, I’m not—no, no, we are not talking about that. I am not talking about the society at large, that you have the right and you can’t even create your own.

ART SPIEGELMAN: You’re talking about Charlie Hebdo.

TARIQ RAMADAN: We are talking here about a policy that was said by Charlie Hebdo over the last years that is mainly targeting the Muslims. My point here is, once again, I’m not—

ART SPIEGELMAN: But why?

TARIQ RAMADAN: I’m not—

ART SPIEGELMAN: Why were they targeting Muslims? Do you think it’s—

TARIQ RAMADAN: I’m not—you know why? You know what? You know why? It’s mainly a question of money. They went bankrupt, and you know this. They went bankrupt over the last two years. And what they did with this controversy is that Islam today and to target Muslims is making money. It has nothing to do with courage. It has to do with making money and targeting the marginalized people in the society.

The point for me now is just to come with you, as somebody who is involved in this, and to come with the principles that you are making now, and to come and to say, look, now, in the United States of America as well as in the West, everywhere, we should be able to target the people the same way and then to find a way to talk to one another in a responsible way, not by throwing on each other our rights, but coming together with our duties, our responsibilities to live together.

I think that what you are saying now could be dangerous if you are not coming to the facts, but just with the impression that their past is similar to the present. Charlie Hebdo is not the satirical magazine of the past. It is now ideologically oriented. And Philippe Val, who was a leftist in the past, now is supporting all the theses of the far-right party, very close to the Front National. So, don’t come with something which is politically completely not accurate.

ART SPIEGELMAN: The focus on the Muslims really had to do with the riots about the original cartoons. It was their responsibility to show those cartoons, and they rose to that occasion admirably. Ever since—if you tell a provocateur, “Be quiet, be nice,” it doesn’t work that well if their mandate is to be provocateurs.

TARIQ RAMADAN: You’re right.

ART SPIEGELMAN: Which is why Siné immediately went out and created a magazine that allowed him to do whatever toxins he had to express. I don’t argue that the cartoons aren’t toxic. I do argue that that toxin is a necessary part of an ecosystem. And Charlie estimably filled that, even though I don’t know its—you probably know it a lot better than I do over the last two years. I know its history and its impulses.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to break, and we’re going to bring back with us, in addition to Tariq Ramadan, professor of contemporary Islamic studies at Oxford University, and Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist, graphic novelist, best known for Maus, we’ll bring in Gilbert Achcar. Stay with us.

Media Options