Topics

Guests

- Kozue Akibayashinewly elected president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

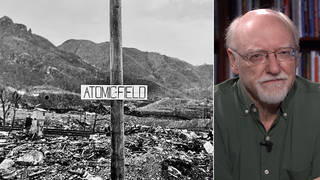

As peace activists gather in The Hague, Japan is moving toward taking a more active military role internationally despite having a pacifist constitution. On Tuesday, President Obama hosted Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for a White House state dinner. The two nations have just unveiled new guidelines for military cooperation. We examine Japan’s growing military role with Kozue Akibayashi, the newly elected president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She also discusses opposition to the presence of some 25,000 U.S. military personnel stationed in Okinawa. “The U.S. military has been granted almost diplomatic immunity to whatever they do. Crimes are committed, but they are not punished. They get away.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Well, as peace activists gather here in The Hague, Japan is moving towards making—taking a more active role militarily, internationally, despite having a pacifist constitution. On Tuesday, President Obama hosted Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for a White House state dinner. The two nations have just unveiled new guidelines for military cooperation.

Well, the new president of WILPF is from Japan, Kozue Akibayashi.

Kozue, thank you for joining us here on Democracy Now!

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: So, as you’re being inaugurated here in this gathering of almost a thousand women from around the world, Prime Minister Abe is in our nation’s capital in the United States. They’re talking about how—they’re welcoming him into the military fold. What is changing in Japan? Can you explain what the peace constitution is—or, should I say, was?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Oh, it still is. It’s our constitution, made in 1946, '47, after the World War II, after Japan was defeated by the Allied countries. And it has—it's called the peace constitution because it has an article, Article 9, that renounces war to settle international disputes and possession of armed forces. That has been there, and that’s still there.

AMY GOODMAN: And it says you can’t have a military, right?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: We cannot have a military, but in reality, we do have a military, and that has been controversial, as well, the military. We don’t call it “military”; it’s called the Self-Defense Forces.

AMY GOODMAN: And it was the U.S. that pushed for that to be included—

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —after Japan was defeated in World War II.

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: But now it’s the U.S. is pushing for it to be amended.

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: It’s both the U.S. and some people within Japan. I think the majority of people in Japan is supporting still the peace constitution. But, well, those who are in power currently, obviously, want to change the constitution so that we can have—we can legitimize the military and even increase the military power, and also increase the military cooperation with the United States. The Self-Defense Forces has been participating in—not operations, but exercises with the United Nations—I mean, with the United States for quite a while. Well, we have lived in—we have been living in that contradiction. And the peace community has been working hard to change or to put it back to what it used to be, the constitution was originally meant to be, but that’s been a struggle.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, you have been a peace activist in Okinawa for a very long time. What is happening in Okinawa today?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Now, is—like, as of now, people are protesting. More people are participating in protesting, nonviolent action on the street, on the sea. There have been a sit-in on the sea, done on the boat, boats, and canoe, even, against that huge Coast Guard ships that have been very brutal against people of Okinawa.

AMY GOODMAN: The U.S. military?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: No, it’s the Japanese Coast Guard. But also, I participated in many of the sit-ins around the gate of military bases in Okinawa. And I have been—

AMY GOODMAN: Are these U.S. military bases?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Yes, U.S. military. Marines, mainly.

AMY GOODMAN: How big is the U.S. military presence in Okinawa?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: In Okinawa, there are a little less than 30,000 soldiers stationed and additional 25,000 dependents and families.

AMY GOODMAN: Why do you object to them being there?

KOZUE AKIBAYASHI: Because it’s our land, it’s our sea, Okinawan people’s lands and sea. And the U.S. military has been granted almost diplomatic immunity to whatever they do. Crimes are committed, but they are not punished. They get away. Many people’s properties have been damaged. The United States military has never, almost, compensated. I have been working on sexual violence by soldiers, the issue on sexual violence by U.S. soldiers, for many years. That has been—that has occurred since 1945, many, many cases.

Media Options