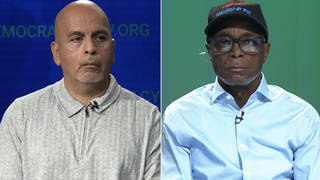

Guests

- Flint Taylorattorney with People’s Law Office who has represented survivors of police torture in Chicago for more than 25 years.

- Darrell Cannonone of dozens of men to come forward with allegations of abuse at the hands of the Chicago police. Darrell says police tortured him in 1983 and forced him to confess to a murder he didn’t commit. He spent more than 20 years in prison, but after a hearing on his tortured confession, prosecutors dismissed his case in 2004. He was released three years later.

Links

Earlier this month, the Chicago City Council approved a $5.5 million reparations fund for victims of police torture. More than 200 people, most of them African-American, were tortured under the reign of Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge from 1972 to 1991. Tactics included electric shocks and suffocation. The reparations package will provide free city college tuition for victims and relatives, counseling services, a memorial to victims, inclusion of Burge’s actions in the school curriculum, and a formal apology. We are joined by two guests: Flint Taylor, a founding partner at the People’s Law Office who has represented survivors of police torture for more than 25 years, and Darrell Cannon, a former prisoner who spent more than 20 years behind bars after being tortured into confessing to a crime he didn’t commit. Prosecutors dismissed Cannon’s case in 2004, and he was released three years later. He has since focused on the roughly 20 men tortured during the Burge era who remain behind bars.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Earlier this month, the Chicago City Council approved a $5.5 million reparations fund for victims of police torture. More than 200 people, most of them African-American, were tortured under the rein of Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge from 1972 to '91. Tactics included electric shocks and suffocation. The reparations package will provide free city college tuition for victims and relatives, counseling services, a memorial to victims, inclusion of Burge's actions in the school curriculum, and a formal apology. Many torture victims were present when the Chicago City Council unanimously approved the reparations package last Thursday. They were recognized by Chicago Alderman Joe Moreno.

ALDERMAN PROCO JOE MORENO: We have some victims of torture here today, and their families, and if they would rise when I call their names: Darrell Cannon; Anthony Holmes; [inaudible]; Mearon Diggins; Mark Clements; Ronnie Kitchen; Marvin Reeves; Stanley Rice; Gregory Banks; Willie Porch; Lindsey Smith: George Powell; Ollie Hammonds; L.C. Riley; Mary Johnson, who’s the mother of torture survivor Michael Johnson; Bertha Escamilla, mother of torture survivor Nick Escamilla; and Carolyn Johnson, the mother of torture survivor Marcus Wiggins. Thank you for your leadership. Thank you for continuing to fight, even though you’re out here—you’ve been out. You’re fighting for those that are still in and for those that are still suffering. Thank you so much.

AMY GOODMAN: Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel then apologized to the police torture victims and their survivors, and thanked them for their efforts to demand justice.

MAYOR RAHM EMANUEL: This stain cannot be removed from our history of our city, but it can be used as a lesson of what not to do and the responsibility that all of us have.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we go to Chicago, where we’re joined by two guests. Flint Taylor is founding partner of the People’s Law Office. For more than 25 years, he has represented survivors of police torture, including Darrell Cannon, who also joins us. Police tortured Darrell in 1983 and forced him to confess to a murder he didn’t commit. He spent more than 20 years in prison, but after a hearing on his tortured confession, prosecutors dismissed his case in 2004. He was released three years later. Since then, he’s focused on the roughly 20 men tortured during the Jon Burge era who remain behind bars.

We welcome both of you back to Democracy Now! Darrell Cannon, can you talk about being in the City Council chamber, the Chicago City Council chamber, as you were recognized and thanked by a city councilmember as they voted on a police torture fund of—what was it? Five-and-a-half million dollars?

DARRELL CANNON: Correct.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what happened to you?

DARRELL CANNON: On November the 2nd, 1983, about 15 all-white detectives invaded my apartment, terrorized me, my common-law wife and my cat. And during that day, through—I was tortured in despicable ways, from them using an electric cattle prod to shock me on my genitals and in my mouth. They tried to hang me by my handcuffs, which was cuffed behind my back. And they tried to play a game of Russian roulette on me with a shotgun, and they ended up chipping my two front teeth and splitting my upper lip.

AMY GOODMAN: And then what happened?

DARRELL CANNON: From there, by the time they finished with me that evening, I was ready to say that my mother committed a crime, if they told me that was the case. The type of things that they did to me, I have never in my life experienced, and I’ll never in my life forget. It was something that you couldn’t even conjure up in a horror movie, because you don’t think that Chicago police officers would stoop this low in trying to obtain a confession. It didn’t matter whether or not I was guilty or innocent. In their minds, any time they pick a black man up, he’s guilty.

AMY GOODMAN: Flint Taylor, you’ve represented Darrell Cannon as well as other people who were the victim of police torture. What—how was this $5.5 million fund arrived at? And what did it take for you to get the City Council of Chicago and the mayor, Rahm Emanuel, to talk about this as a police torture fund?

FLINT TAYLOR: Well, there’s a long history, as you mentioned, of fighting against police torture in this city, starting decades ago. And there’s been tremendous movements, generational, intergenerational movements, interracial movements, that have fought, first to get Burge fired many years ago, later to get him indicted in 2008 for perjury and obstruction of justice, and to get him convicted and sent to the penitentiary, federal penitentiary. And now, this particular movement was a wonderful coming together of young people, older people, an organization called the Torture Justice Memorials and other young organizations, Black Lives Matter, We Charge Genocide, and all of that came together politically to deal with aldermen, to deal with demonstrations, to marches. There was a great up—not uprising, but an uplifting experience, that ultimately led, in the middle of what appeared to be a tough election cycle, to the mayor and his people and a majority of aldermen dealing with this issue some decades after the torture took place. And that really is the reason that we were successful in getting this unique and historic reparations package.

To answer your other question, there are about 55 living men—55 or 65, we estimate—who were tortured, who will be eligible for the reparations. We felt that, symbolically and in a real way, that $100,000 per person would be something that would be meaningful, although certainly does not fully compensate anyone for being tortured. But there was no legal recourse for these men: The statute of limitations had run out. So, the entire package, as you mentioned, not only the money, but the services—psychological counseling for family members and the men who have been tortured; the education, not only for the men, but in the public schools, to have it taught; to have a narrative, the narrative we’ve been fighting for, about police torture all these years, that was disbelieved and laughed at and denigrated in the same way Homan Square is denigrated and laughed at by the city and the police, that now the narrative has changed and will be taught in a different way.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Chicago Police Commander Jon Burge served a short prison sentence for perjury and obstruction of justice before his release last year. Statistics compiled by your office, Flint, the People’s Law Office, show Chicago has paid at least $64 million in settlements and judgments in civil rights cases related to Burge’s police abuses alone. The Chicago Reader reported some of Burge’s techniques may have been learned in Vietnam, where he served as a military policeman. How long did Jon Burge serve? And, Darrell Cannon, did you meet him at any point when you were being beaten and tortured?

DARRELL CANNON: No, ma’am. I didn’t personally meet him. He was at the station that day, and he assigned his own personal, hand-picked soldiers to come and get me. Peter Dignan, the most vicious detective out of all of them, he’s the one that did all the announcing of Jon Burge any time they did a fundraiser. He took him to his house on holidays and fed him with his family and etc. So, as far as I’m concerned, he wasn’t directly there, but indirectly, oh, yes, ma’am, he was there.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Darrell Cannon, will you benefit from this $5.5 million police torture fund?

DARRELL CANNON: Yes, ma’am.

AMY GOODMAN: And—

DARRELL CANNON: But the thing that I’m most proud of is the fact that the curriculums in schools will be taught now from eighth grade through tenth grade, something that has never been done in the history of America. And because of this, I play a small role in trying to bring positive change to the police department. And I’ll continue to work on behalf of those who are still in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, you had been offered money before, is that right? In a settlement?

DARRELL CANNON: Yes, ma’am.

AMY GOODMAN: How much?

DARRELL CANNON: Yes, ma’am. Yes, ma’am. And I—well, we can’t disclose exactly how much, but let’s say it was over a million. But I refused to accept it, because, far as I was concerned, this was hush-up money, for me to go away, to be quiet and to speak no more about it. But the picture has always been bigger than Darrell Cannon, you know? What about the other Darrell Cannons who were not as fortunate as I was to have a supporting system on the streets, as well as to have competent lawyers that stood with me through decades in litigation? And we finally achieved the victories that we wanted, on that level. But as I said before, the case is not over with. The glass is only half full.

AMY GOODMAN: And those other Darrells, Darrell Cannon, those that are still in prison—

DARRELL CANNON: Oh, yes, ma’am.

AMY GOODMAN: What is happening with them?

DARRELL CANNON: Oh, yes, ma’am. We are hoping now that the litigation that has been slowly dragging out, due to the judicial system, will now be stepped up. Seeing how the City Council, as well as the mayor, has come to grips with this horrible tragedy, I’m hoping that the judicial system will also take a leading role and speed up all the hearings into the police brutality for those that are still in prison, and in doing so, let the evidence speak for itself. If the evidence shows that these sadistic, vicious individuals posing as cops did in fact torture them, then give all of those men new trials in front of a fair and impartial judge.

AMY GOODMAN: We have 30 seconds, Flint Taylor. Do you see that happening? And overall, do you see what’s happened in Chicago as a model for other cities?

FLINT TAYLOR: It’s definitely a model, not only for other cities, but all across the world, I would think, that it happened here in Chicago, that if there are movements to take it to other cities, as we see there are across the country, that they can demand the same kind of things that the movement here demanded. In terms of hearings, we’re very hopeful that people who are still in prison after all these years and decades will get fair hearings. And a judge has ordered that they be appointed lawyers to look into their cases and to bring them back to court. So we are hopeful on both fronts, but the message has to get out, as you are taking it to the country for us, so that others can see the example set here and that “reparations” can be a word that is broad and accepted across this country when it comes to police violence and police brutality.

AMY GOODMAN: Attorney Flint Taylor, I want to thank you for being with us, one of the founding partners of People’s Law Office in Chicago, and Darrell Cannon, tortured by Chicago police, now out fighting for those who remain in prison.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, upstate New York, there’s a struggle going on. We’ll speak with a filmmaker, Josh Fox, who was one of 20 people arrested this week at Seneca Lake. Stay with us.

Media Options