Topics

Guests

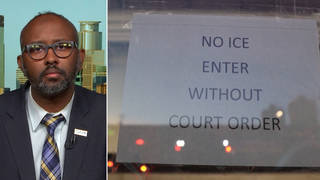

- Malik Rahimco-founder of the Common Ground Collective, which helped bring thousands of people from all over the world to help rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. He is also one of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party.

We continue our coverage of the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina by speaking to Malik Rahim, co-founder of the Common Ground Collective and one of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party. In 2005, he and the Common Ground Collective helped bring thousands of people from all over the world to assist in the rebuilding of New Orleans. Just weeks after Hurricane Katrina hit the city, Malik took us around the neighborhood of Algiers, where he showed us how a corpse still remained in the street unattended, lying right around the corner from a community health center. Malik returns to Democracy Now! to talk about the storm a decade later.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We continue our coverage of the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. In a moment, we’ll be joined by Malik Rahim, co-founder of the Common Ground Collective, which helped bring thousands of people from all over the world to help rebuild New Orleans after the storm. But first, I want to rebroadcast a part of the interview that we did with Malik on Democracy Now! just days after Katrina hit in 2005, when we went down to New Orleans and the community, the neighborhood of Algiers. Malik took us around to the corner at a community health center, a multi-service center, and he showed us how a corpse still remained on the street unattended. Let’s go back to that day.

MALIK RAHIM: You could basically smell it from right here. You know, and the police, they pass by. They look at it, and they ain’t gonna do nothing, you know, to pick it up.

AMY GOODMAN: Malik then walked us down the driveway next to the health center and lifted up a sheet of corrugated metal marked with an X, revealing the dead body underneath.

MALIK RAHIM: Now, his body been here for almost two weeks. Two weeks tomorrow. All right. That this man’s body been laying here. And there’s no reason for it. Look where we at? I mean, it’s not flooded. There’s no reason for them to be—left that body right here like this. I mean, that’s just totally disrespect. You know? And I mean two weeks. Every day, we ask them about coming and pick it up. And they refuse to come and pick it up. And you could see, it’s literally decomposing right here. Right out in the sun. Every day we sit up and we ask them about it. Because, I mean, this is close as you could get to tropical climate in America. And they won’t do anything with it.

AMY GOODMAN: Malik, do you know who this person is?

MALIK RAHIM: No. But regardless of who it is, I wouldn’t care if it’s Saddam Hussein or bin Laden. Nobody deserve to be left here, and the kids pass by here and they’re seeing it. I mean, the elderly. This is what’s frightening a lot of people into leaving. We don’t know if he’s a victim of vigilantes or what. But that’s all we know is that his body had been allowed to remain out here for over two weeks.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re standing right outside the health clinic. Its doors are chained. The building is not seriously damaged. Have you reached people there? What authorities have you talked to to pick up this body?

MALIK RAHIM: We done talked to everyone, from the Army to the New Orleans police to the state troopers to—I mean, we done talked to everybody who we can. I even talked to Oliver Thomas, who is the councilman-at-large, yesterday about this body. He said he was surprised to see that this body is still there. But it’s two weeks, two weeks that this man been just laying here.

AMY GOODMAN: As Malik Rahim was speaking, as if on cue, every level of authority he mentioned drove by. There’s a dead body right here. Is—who are you with?

SOLDIER: We’re with Bravo 15.

AMY GOODMAN: Which is?

SOLDIER: The Cav.

AMY GOODMAN: Army?

SOLDIER: Army, yes. Regular Army.

AMY GOODMAN: There’s a dead body right here. Can you guys pick it up?

SOLDIER: I don’t think we can pick it up, but we can call the local authorities to come and pick it up.

AMY GOODMAN: This gentleman who lives in the neighborhood said that they have been trying to get—here, let me ask these guys, too. Excuse me. Excuse me. Hi. There’s a dead body right here. Can Louisiana state troopers, can you pick it up?

LOUISIANA STATE TROOPER: You need to talk to our public information officer, Ma’am.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s been here for two weeks. We filmed it last week, and gentleman over here said he’s been trying to get it picked up for two weeks. And Louisiana state troopers, the police, the Army, no one has responded. We’re looking right over at it right there.

LOUISIANA STATE TROOPER: You need to talk to our public information officer and contact him at the troop.

AMY GOODMAN: Your name is?

LOUISIANA STATE TROOPER: You need to talk to our public information officer.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you know about the body?

LOUISIANA STATE TROOPER: You need to talk to our public information officer.

AMY GOODMAN: Sir, do you know about the body over there?

LOUISIANA STATE TROOPER: Ma’am, you talk with our public information officer.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you know what they should do to get this body removed?

ROBERT GONZALEZ: I have no idea. I can’t tell you. I don’t know. There’s been several people over here looking at it.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Homeland Security that just went by. Sir, what were you saying?

ROBERT GONZALEZ: There’s been several people over here looking at it, but, you know, like I said, I haven’t seen anybody take it.

AMY GOODMAN: Several Army guys?

ROBERT GONZALEZ: Army. I’ve seen police over here looking at it. Seen ambulances looking at it. That’s about it.

AMY GOODMAN: That was a part of our coverage 10 years ago in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. That last speaker, Robert Gonzalez, was with the Army National Guard, one of the many different levels of law enforcement that drove by within minutes of us going near that corpse. The body had been there for 13 days at that point.

Well, for more, we go back to New Orleans, Louisiana, where we’re joined by Malik Rahim, co-founder of the Common Ground Collective, one of the founders of the Louisiana chapter of the Black Panther Party before that.

Malik, it’s hard to ever forget that day. Talk about what happened to that body and also what’s happened to your city, New Orleans, in this past 10 years.

MALIK RAHIM: Well, first of all, it’s an honor to be on your show once again.

What happened to the body, I would say the next day after it was viewed on Democracy Now!, they picked him up. They picked up that one and other bodies that was laid out in Algiers. All of a sudden, it was like you had waved a magic wand, you know, by bringing awareness to the tragedy of Katrina, that they started making a move.

Over the 10 years, you know, New Orleans is still a story of two cities. You know, if you’re white or if you’re part of that privileged black class or free people of color class, then, you know, I mean, it’s recovered. But if you’re poor and part of that African or Maroon class, then it’s like the hurricane just happened last year.

Right now we’re in the midst of some of the most violent times in the history of this city. And it’s only because of the fact that that 10-, that eight-year-old, that six-year-old child, that 12-year-old child, that was in the Convention Center and abandoned in that Superdome, now they are 22, 16, full of rage, because we did not deem—have any trauma counselors there with them through this.

We have unemployment is over 50 percent. And the ones who are blessed with a job, the disparity of wages is that they make three times less than their white counterpart. Public housing is no more. They displaced everyone. The only equal opportunity employer is the drug dealer. So now we’ve been in the midst of a drug war. And the tails of it is just in the last two days there has been maybe six shootings. So, again, you know, by the fact that our administrations—and I’m talking about on all levels—refused to address the real, pertinent issues of the aftermath of Katrina is the reason why we are in this way, in this dilemma now.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to ask you a question. Kristen McQueary of the Chicago Tribune Editorial Board recently wrote a piece about Chicago’s financial crisis titled “In Chicago, Wishing for a Hurricane Katrina.” She writes, quote, “I find [myself] wishing for a storm in Chicago—an unpredictable, haughty, devastating swirl of fury. A dramatic levee break. Geysers bursting through manhole covers. A sleeping city, forced onto [the] rooftops.” She later apologized for offending the entire city of New Orleans and beyond. Your response in this last minute we have with you, Malik?

MALIK RAHIM: Well, again, I think that it was totally disrespectful for a person to say that, because, I mean, as an African American, more of my people was killed in the aftermath of Katrina than at any time in the history of this nation. Never at one time have we lost over a thousand lives. And we lost almost 1,200 just in the Lower Ninth Ward. So I feel offended with it.

AMY GOODMAN: And what would you say to President Obama today as he makes his way to the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans?

MALIK RAHIM: I wouldn’t know what to tell him, because of the fact that, you know, our people have seen over six years of President Obama administration, and nothing have changed.

AMY GOODMAN: But they’re hailing New Orleans as a great victory, a remarkable trajectory of progress.

MALIK RAHIM: Yeah, again, that’s among that white and that privileged black class. But that’s only part of this population. And it’s not even the majority. That’s that 40 percent.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you for being with us, co-founder of the Common Ground Collective, and for being there for these 10 years since Hurricane Katrina, not to mention before—Common Ground Collective, which helped bring thousands of people from around the world to help rebuild New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina—speaking to us from New Orleans.

Media Options