Related

Guests

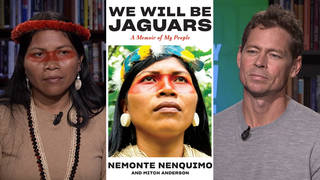

- Shimon Dotanaward-winning filmmaker and director of The Settlers. He teaches political cinema at NYU Graduate School of Journalism and film directing at The New School.

As Israel faces international condemnation over its plan to build 153 new settlement homes in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, the watchdog group Peace Now reports Israel’s defense minister has approved the construction of the new Jewish-only homes last week. The plan sparked swift criticism from U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, who called the settlements “an affront to the Palestinian people and to the international community.” In response, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Ban Ki-moon’s criticism gives “a tailwind to terrorism” and that the “U.N. lost its neutrality and moral force a long time ago.” This comes as President Barack Obama spoke at the Israeli Embassy to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, saying, “We are all indeed Jews.” We examine the history and consequences of decades of Israeli settlement construction on Palestinian lands in an interview with Shimon Dotan, the director of an extraordinary new film, “The Settlers,” which just had its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival. “It is such a heated and often discussed topic, but I find that so little is known about it, and often the discussion is misinformed,” Dotan says.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from the Sundance Film Festival here in Park City, Utah. Israel is facing international condemnation over its plan to build 153 new settlement homes in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. The watchdog group Peace Now reports Israel’s defense minister approved the construction of the new Jewish-only homes last week. The plan sparked swift criticism from U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, who called the settlements, quote, “an affront to the Palestinian people and to the international community.”

SECRETARY-GENERAL BAN KI-MOON: Continued settlement activities are an affront to the Palestinian people and to the international community. They rightly raise fundamental questions about Israel’s commitment to a two-state solution.

AMY GOODMAN: In response, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Ban Ki-moon’s criticism gives, quote, “a tailwind to terrorism,” and that, quote, “The U.N. lost its neutrality and moral force a long time ago,” end-quote.

PRIME MINISTER BENJAMIN NETANYAHU: [translated] The words of the secretary-general only bolster terrorism. There is no justification for terrorism, period. The Palestinian murderers do not want to build a state. They want to destroy a state. And they declare it publicly.

AMY GOODMAN: This comes as President Barack Obama spoke at the Israeli Embassy to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, saying, quote, “We are all indeed Jews.”

Well, we now turn to an extraordinary new film called The Settlers, which just had its world premiere here at the Sundance Film Festival. The documentary examines the history and consequences of decades of Israeli settlement construction on Palestinian lands. We’ll be joined by the film’s director in a minute, but first I want to play a clip from the film. Talia Sasson, the former head of the Israeli State Prosecution Criminal Department, explains the findings of an official Israeli government report on the settlements.

TALIA SASSON: [translated] I listed 105 outposts built between 1995 and March 2005. The findings of my report were that the entity behind the establishment of the outposts was the state of Israel, acting behind the government’s back, illegally, but with the involvement of various government ministries, settlers, local councils in the territories. They are the ones that used state funds to build those outposts, and all of this was done illegally. The illegality was institutionalized. The government couldn’t decide on the establishment of new settlements, because the Americans were given verbal commitments, and the prime minister didn’t want to violate them. But there was still the desire to build new settlements, so they found a system whereby the government is “unaware” that settlements are being built with government funds.

AMY GOODMAN: That was a clip from the just-released documentary film, The Settlers. For more, we’re joined by the film’s director, Shimon Dotan, an award-winning filmmaker. He teaches political cinema at NYU Graduate School of Journalism and film directing at New School University.

Welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us.

SHIMON DOTAN: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the history of the settlements. While we hear a lot about what’s happening every day, how 400,000 Jews came to settle in these Jewish-only communities in the occupied West Bank is critical to understand today.

SHIMON DOTAN: One of the reasons that I’ve made The Settlers is because it’s such a heated and often discussed topic, but I find that so little is known about it. And often the discussion about it is misinformed. I started the film as an attempt to explore the present reality in the West Bank, but soon I understood that it’s very important to go back to the roots, to the very beginning of the settlements.

What I found out, which is not a secret, but it’s—I think it’s relevant to put it up front, is that at no point in time any Israel government decided that it’s in the best interests of the state of Israel to keep settlements in the West Bank. It all happened in a sort of dragged way, in—as Talia Sasson explained in the clip that we’ve just seen. There was initiative from the settlers that was driven—that were driven often by religious, ideological or political reasons. And we are facing today a reality which is, in my view, the most critical to the state of Israel, to the region at large, that took us there without a calculated and educated decision from the government of Israel.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the first Jewish settlers, how they ended up there. Talk about the numbers of people right now that are settlers in the West Bank.

SHIMON DOTAN: After the—well, maybe I’ll take one step back. In May 1967, there was a celebration of the Israel Independence Day at a yeshiva called Mercaz Harav Yeshiva, where a charismatic rabbi named Tzvi Yehuda Kook started an outcry longing for the lost biblical sites of Israel: “Where is our Hebron? Where is our Nablus? Where is our Jericho?” Three weeks later, Israel took possession of Jericho, Nablus and Hebron. The students, his disciples that were there at this particular moment, became the leader of the settlement movement, where its primary ideology is that Israel and the people of Israel will get redemption by populating the land of the West Bank. So, very early on, it was almost a whimsical attempt from individuals to go back to sites that have biblical or recent memory presence among those Israelis.

At the same time, it was a clear intention of the government of Israel to engage in a land-for-peace negotiation with the neighboring [Arab] states. The government, Levi Eshkol, Israel’s prime minister at the time, allowed these one or two settlements to take hold. And later on, it had become—you know, it mushroomed in a way that’s hard to fathom. We have today about 400,000 settlers in the West Bank. I would say about 80,000 of them are ideologically or politically driven, religiously driven. And the vast majority is there for, let’s call it, quality-of-life reasons—cheaper housing, etc.

AMY GOODMAN: The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin by an extremist Israeli Jew, talk about the significance of this.

SHIMON DOTAN: Well, that’s a watershed. Everything changed after the assassination. And I think one of the reasons that many in Israel do oppose the settlement enterprise and whatever it implies is that there is an inevitable process, inevitable evolution: When you create a reality of settlements under occupation of the population within that territory, extremists tend to flourish, and you put the people in this region in an eternal conflict with their immediate neighbors. Now, before Rabin was assassinated, 20 year earlier—20 years earlier, he was a very strong opponent of the settlement enterprise. He called clearly in 1974 the Gush Emunim, which was the driving force behind the early settlers—he called it a cancer in the democratic fabric of the state of Israel. It didn’t take long: 20 years later, he was murdered.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about the man who murdered him.

SHIMON DOTAN: Well, I have—his name is Yigal Amir. He’s an extremist Jew that believed that he has to take an action in order to save the settlements, so to speak, to prevent the Oslo process, which was a peace—an attempt to a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians, to take hold. And tragically, he—it was an extremely successful political assassination. After Rabin’s death, Oslo fell apart, and Israel, since then, more or less, was governed by right-wing governments.

AMY GOODMAN: You have extremely powerful moments, poignant moments—a Palestinian woman saying, “Get off my land,” to Israeli settlers who have come onto the land. “These are my olive trees. This is my land.”

SHIMON DOTAN: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about that, and also your interview with the head of Al-Haq, the human rights organization in Ramallah.

SHIMON DOTAN: Well, at first, I thought I’m going to interview and talk about and present only settlers. But it was clear that I cannot just stay away from those who are terribly affected by this presence. And so, we have this woman that actually she has just a few olive trees, and she has a stick in her hand, and she comes to some of the settlers that took a hold of her olive trees, and she threatened them with this stick, says, “Don’t dare touch my olive trees!” Well, you know, it’s an iconic moment, and it does represent a reality that became now the day-to-day life of the people there.

Raja Shehadeh is a human rights activist in the West Bank. He’s based in Ramallah. And he presents, in a very eloquent way, the experience of Palestinians after the settlements actually infiltrated throughout every possible corner of the West Bank.

But I must say—if we have time, I don’t know—I think it’s extremely important to understand what drove the settlers. And it’s not something that will go away. And one of the purposes that I had in making this film is to really inform and have a better understanding that will take us away from the black-and-white depiction of the reality. And I hope that the movie does that.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Shimon Dotan, who’s an award-winning filmmaker. His latest film premiered here at the Sundance Film Festival. It’s called The Settlers. The youth group—talk about Gush Emunim, the significance of this, and the violence the settlers engage in.

SHIMON DOTAN: Well, the pattern that was established by the early Gush Emunim members—it started with Moshe Levinger; at first, he established the Jewish settlement inside Hebron—became a pattern that has been used throughout the years. Tragically, today, almost 50 years after Israel took possession of the land of the West Bank, a new group of young settlers—they call them the hilltop youth—are engaging in similar tactics. The main difference may be that they are probably less educated, they are more extreme, and they stop at nothing. But the pattern that was established 50 years ago seems to relive itself once again. And I find it terribly concerning. They may not have the power, the political power, to drive the dialogue, but they most definitely have the ability to prevent or to stop, by action of violence against the other side, any attempt at moving forward in any process or agreement with the Palestinians.

AMY GOODMAN: The significance of what Ban Ki-moon said, the—once again condemning the expanded settlements in the West Bank?

SHIMON DOTAN: I find it almost irrelevant, if I may say so. The settlements in the West Bank are a massive presence, and 135 new houses are meaningless. At every point in time, there is ongoing construction in the West Bank. The settlements are expanding, are flourishing. More and more people are moving into the West Bank. And if I think of—that, you know, it’s a country that was established on ideals of secular liberalism, on equality. And the push to the settlement enterprise, it forces the state of Israel to hold a strong grip with the occupation of the West Bank. That’s what really is relevant. This small hundred houses or less, that’s—it seems to me, that’s not the issue. We have to have a more far-reaching goal and more—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you see will end the occupation?

SHIMON DOTAN: Well, I wouldn’t even try to propose a solution. What I do know, that if the prime minister of Israel does not wake up every single morning and put a mantra in front of his eyes—”What can I do today to bring peace to the region?”—he’s not doing his job.

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, it doesn’t matter if it was Likud or Labor.

SHIMON DOTAN: Oh, absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: The settlements flourish.

SHIMON DOTAN: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And the insult, not to mention the actual killings of Palestinians in the West Bank, what it means to them every day, they and their ancestral homes being pushed out by many Jews who don’t even come from the area. How many of them, for example, come from New York, come from Brooklyn?

SHIMON DOTAN: Yeah, I don’t have the numbers. But the point is that Jews that are coming through the Law of Return in Israel are allowed to gain citizenship, are offered citizenship as soon as they come to the state of Israel. However, those who come directly to the West Bank enjoy the same benefits. But you mentioned the violence—

AMY GOODMAN: And Palestinians, on the issue of the right of return?

SHIMON DOTAN: No, there is no status for Palestinians to gain the right of return. This is a non-existing element. But you mentioned the violence before that is practiced against Palestinians, which is true, but I must say that the violence against Israelis, against settlers, is quite wider, very present. And we can say that that—what I mentioned before—that we are facing an inevitable evolution. This violence is there to stay. And if they may be, you know, idle for a day or for a week or for a month, it surely will come back. And every time it comes back, it comes back in a stronger and more vicious form.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you very much for being with us. Shimon Dotan is the award-winning filmmaker. His latest film, The Settlers, premiered here at the Sundance Film Festival. He teaches political cinema at NYU Graduate School of Journalism and film directing at New School University in New York.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, the story of Jim—that’s James Foley—the first American to be killed by ISIS. Stay with us.

Media Options