A new report on the devastating harm of policies that criminalize the personal use and possession of drugs finds that in 2015 police booked more people for small-time marijuana charges than for murder, non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery and aggravated assault combined. The report also showed African-American adults are more than two-and-a-half times as likely as white adults to be arrested for drug possession despite comparable rates of drug usage. This comes as four states have legalized recreational marijuana use and five more will vote to do the same next month. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union released the findings Wednesday with a call for states and the federal government to decriminalize low-level drug offenses. We speak with Tess Borden, author of the report “Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States.”

Transcript

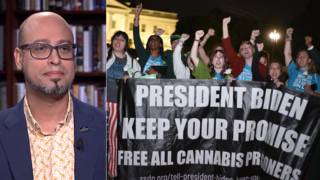

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We turn now to a new report that documents the “devastating harm” of policies that criminalize the personal use and possession of drugs. Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union released the findings Wednesday with a call for states and the federal government to decriminalize low-level drug offenses, which, it says—the report says, account for more arrests than any other crime.

AMY GOODMAN: Last year, police booked more people for small-time marijuana charges than for murder, non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery and aggravated assault combined. This comes as four states have legalized recreational marijuana use and five more will vote to do the same next month. This is part of a video that accompanies the new report.

NARRATION: Corey Ladd is a 27-year-old man that got sentenced to 20 years for half an ounce of weed.

LISA LADD: When Corey gets out of prison, Charlie will be about 18 years old.

Hi, Corey, I was just talking about you missed out all the little things of Charlie’s life.

COREY LADD: I definitely don’t think it’s fair whatsoever. And I don’t believe that I should be taken away from my family for 20 years for it.

NARRATION: Every 25 seconds, someone is arrested in the United States simply for possessing drugs for their personal use. Around the country, police make more arrests for drug possession than for any other crime—over 1.25 million arrests per year.

CARMEN: Steven is not here with us right now, because he’s in prison. The last time he was arrested, I think it was for like drug paraphernalia, and eventually they gave him five years.

BRIDGETTE: Steven was—at one time, he was a provider. His not being there has definitely impacted, you know.

MAJOR NEILL FRANKLIN: Blacks, whites, people of color, we all use and sell drugs at relatively the same rates. But we enforce our policies in these poor black and brown communities.

KENNETH HARDIN: In my opinion, it is not justice. The definition of insanity is to keep doing something over and over again and expect a different result. So, maybe we should try something different.

NARRATION: The human toll of criminalization is out of control. It is time to decriminalize the personal use and possession of all drugs.

AMY GOODMAN: That video accompanies the new report by Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union titled “Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States.” Its principal author joins us now to discuss its findings. Tess Borden spent a year visiting with people jailed on drug possession charges around the country, as well as prosecutors and other key players in the system. She focused on the states of Louisiana, Texas, Florida and New York.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Tess. Lay out your findings.

TESS BORDEN: Thank you. It’s terrific to be here.

Human Rights Watch and the ACLU undertook this yearlong investigation into just how failed the law enforcement approach to drug use is. And what we found is, first, that the scale of enforcement is absolutely massive. Every 25 seconds, someone is arrested. That accounts for 1.25 million arrests per year, more arrests, as you said in the opening, than any other crime, three times more than all violent crimes combined, five times more than drug dealing. So, the scale is just absolutely incredible and devastating.

Secondly, we found that the consequences of those arrests and prosecution can be sometimes lifelong, not only for individuals, but also for families. On any given day in the United States, some 140,000 people are behind bars just because they possessed a small amount of drugs for their own personal use, while each day tens of thousands more are cycling through jails and prisons, struggling to make ends meet on probation and parole.

We also found that a conviction for drug possession, often at the felony level, because in 42 states small amount of possession can be a felony offense—we found those convictions can keep individuals, and sometimes, again, entire families, out of public benefits, such as food stamps or Section 8 housing. It can make it hard to get a job, rent a house, next month to vote. And for noncitizens, of course, it can result in deportation.

And then, we also found that the enforcement of these laws is disproportionately impacting communities of color and the poor, without justification, just to drill down there. We know around the country black and white people use drugs at equivalent rates, and yet a black person is two-and-a-half times more likely to be arrested for simple drug possession than a white person. In many states, that ratio is significantly higher. And absolutely no state is at one-to-one. So, a black person is more than five times more likely to be arrested for, again, simple drug possession for personal use than a white person in North Dakota, New York, Minnesota, Montana, Iowa, Vermont. Here in Manhattan, a black person is 11 times more likely to be arrested than a white person. Again, that’s despite equivalent rates of use. So, these are racial disparities. But more importantly, under human rights law, this is racial discrimination.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: One of the interesting things is, you—the core of the report is all these interviews that you did with about 149 people, and most people think, “Well, a person gets arrested on a drug charge, they deserve it.” But you look at the entire impact, not just on that person, but on their family, on their whole situation, and also on their prospects once they get out of jail in terms of being able to reconstruct their lives. Can you talk about that, as well?

TESS BORDEN: Yes, absolutely. So I met 149 people, 64 of whom were in custody when I met them, so in jails, in prisons. And what I found across the board was that these are mothers and fathers, these are friends and family members, who have been taken out of their lives and for whom it’s really hard to move on after the fact of prosecution. I met people like Corey Ladd in the video, like Steven’s family.

To flesh it out a little bit, Corey Ladd has a four-year-old daughter. She’s going to be five. We saw the picture of her. She’s going to be five in January. He was arrested in December, before she was born. He’s never held her. He’s never played with her outside of prison. The first time he held his baby girl in his arms was in the infamous Angola prison in Louisiana. Charlie, the little girl—

AMY GOODMAN: This is for possessing half an ounce of marijuana?

TESS BORDEN: This is—absolutely, possessing half an ounce of marijuana. His prior convictions were also for drug possession. And because he was considered under Louisiana law a habitual offender, because he had habitual drug use, he was sentenced to 20 years. Twenty years. And so, his little daughter, Charlie, now thinks she visits him at work, when they go to prison. She could be a teenager going off to college by the time he comes home. And she’ll know by then that prison isn’t where her dad works.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us about Nicole.

TESS BORDEN: Nicole is a mother of three young children I met in the Harris County Jail in Houston, Texas. Nicole was detained pretrial on two charges, both for residue inside drug paraphernalia. The prosecutors could have prosecuted her for misdemeanors, but instead they sought felony charges. Nicole was detained for three months, away from her young children, away from her newborn. The little baby, who I call Rose, learned to sit up on her own, when her mother was inside. And Nicole’s husband brought Rose to the jail. And when you visit someone in jail, there’s glass in front of you, and you often have to speak through a telephone. And so, the baby couldn’t, you know, reach out and feel her mother. Nicole couldn’t hug her, couldn’t congratulate her, because the baby doesn’t understand how to use a phone.

Nicole eventually pled guilty. In exchange, the prosecutor dropped one charge, and Nicole got a felony conviction for possessing 0.01 grams of heroin inside a plastic baggie, inside an empty baggie. Nicole would do a few more months in prison, in a Texas prison, and then she’d get to go home to her children. But now she’d be a, quote-unquote, “felon.” Now she would be a drug offender. And so, Nicole tells me, beyond even the months behind bars, what this meant was she was going to be punished for the rest of her life. She was in school. She was seeking a degree in business administration. She said she’d have to drop out of school, because now she wouldn’t qualify for student financial aid as a felon and a drug convict, quote-unquote. And she would lose—I’ll hurry up—she would lose food stamps. She would no longer be able to rent in her own name. She would no longer be able to feed her children. And she said, “You know, this is my whole life right there.” And for what?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: You also wrote about Trisha Richardson in Florida, who was convicted on a drug charge at the age of 18, has never been able to vote. Talk about the impact on voting disenfranchisement as a result of these convictions in several states.

TESS BORDEN: Absolutely. So, three states, including Florida, disenfranchise people for felony convictions for a lifetime. Many other states have some level of disenfranchisement, whether it’s for a period of years or while one is finishing one’s sentence. And so, Trisha said, you know, she—you know, she had recalled registering to vote and that that was now, you know, a relic of the past, a fond memory that she’d never be able to capitalize on. And people told me across the board that they felt as though, you know, this conviction, whether it separated them from the voting box or other benefits, meant that their voice didn’t matter, meant that they were no longer really a citizen who mattered in the United States. And for—as we look at next month, going into an important election, felony disenfranchisement is literally keeping out people out of our democracy. And we know that drug possession arrests are, you know, the number one cause of people entering into the system that could be disenfranchising them.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, I wanted to ask you—now, as we’re seeing in recent years the spread of the heroin epidemic, especially—

TESS BORDEN: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —in white communities across the country, you’re suddenly seeing all of these ads on radio and television with a more sympathetic portrayal of the impact of drugs. Do you think that this has a potential to be able to move politicians finally to say, “Well, maybe we ought to reconsider some of our drug laws”?

TESS BORDEN: Yeah, well, this is precisely why Human Rights Watch and the ACLU are intervening at this time, are coupling our call for decriminalization with a strong call for investment in public health approach. We know, 45 years after the drug war was declared, that it hasn’t stopped rates of drug use, and it hasn’t stopped drug dependence, as we see with opiate use right now. So we’re saying we need to invest in a stronger public health approach. We need more evidence-based prevention, education around the risks of drug use and dependence, and voluntary treatment affordable in the community. I do think there’s been a very commendable shift in some policymakers’ and officials’ language towards public health. I would just caution, though, that we don’t invest stronger into the failed criminal justice approach, when we’re—you know, we’re afraid of drugs in this country right now. And I think what we need to say is most people who use drugs don’t become dependent. You know, the opiate epidemic is devastating, and it is tragic. And those people, though, deserve a public health approach instead.

AMY GOODMAN: So you’re calling for decriminalization of drugs.

TESS BORDEN: Absolutely. We’re calling for the decriminalization of personal use and possession of all illicit drugs. That includes marijuana. That includes heroin, methamphetamines, cocaine—all drugs. And what we’re saying, to be quite clear, is not that everyone should go out and use drugs. What we’re saying is, for those people who use drugs and don’t harm others, the criminal law is simply inappropriate. For those people who use drugs and develop dependence, they deserve—they have a right to a health-based approach instead. And the state can still use other laws in place if people do put others in harm’s way. We still, you know, criminalize driving under the influence for alcohol. We can treat drug use, personal drug use, like we do alcohol consumption.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you so much for joining us, Tess Borden, the Aryeh Neier fellow at Human Rights Watch and the American Civil Liberties Union. She’s the author of the new ACLU-HRW joint report, “Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States.” We’ll link to it at democracynow.org. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

Media Options